Improving community college graduation rates will also help ensure that New York-based businesses in many of the fastest growing industries have the skilled employees they need to compete. In researching this report, we interviewed more than two dozen New York-based employers and industry leaders in occupations such as health care, transportation, auto maintenance and construction—fields that tend to pay middle-income salaries and which have long hired employees with relatively low levels of educational attainment. Almost all of them told us that they are increasingly looking to hire college graduates. The employers we interviewed did not always make a sharp distinction between an associate’s and bachelor’s degree, but they clearly expressed that the future belongs to those with a solid postsecondary education and credential.

“It’s even helpful for building supers to have at least a community college degree today,” says Eugene Schneur, managing director of Omni New York, a company that rehabs and maintains affordable housing across the five boroughs. “As technology evolves with boilers and energy saving equipment in buildings, supers need to be computer literate to run them properly.”

“There’s going to be a big shift toward middle-skill jobs in health care, and I definitely think community college graduates are going to be important in that shift,” adds Bill Stackhouse, director of workforce development at the Community Health Care Association of New York State.

Several employers we interviewed say that finding employees with the skills they need is often a challenge, even in a sluggish economy when so many people are out of work. But matching skills to open positions will undoubtedly become a much bigger hurdle for local businesses when the economy finally heats up, especially since many key middle skill occupations—from cable installers and nurses to auto maintenance technicians and pest control workers—employ large numbers of baby boomers who are expected to retire in the next decade. In fact, the share of jobs requiring education beyond high school more than doubled between 1973 and 2008, from 28 percent to 59 percent, according to Anthony Carnevale, director of the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. Carnevale’s research estimates that by 2018, 63 percent of jobs nationwide will require some form of postsecondary degree.

As we detail in this report, there are also significant public costs to the high community college dropout rate. CUNY’s community colleges receive most of their public funding through a mix of city and state operating aid, tuition assistance from the state and federal Pell grants. At present, the majority of these public funds subsidize college students who do not graduate.

Overall, we estimate that the combined public cost for each community college dropout in New York City is roughly $17,783. This breaks down as follows:

-

Community colleges in the city received $8,719 in base operating aid from New York State and New York City for each student who later dropped out.

-

Community college students received roughly $6,245 in federal Pell grants before dropping out.

-

Community college students in New York received about $2,819 in aid from the state-funded Tuition Assistance Program (TAP) before dropping out.

There are other significant costs to New York City from the high dropout rate at the city’s community colleges. For instance:

-

The income lost to a single cohort of students entering CUNY in 2004 in one year was approximately $86 million (of which $19 million consisted of lost tax receipts).

-

The one-year cost in terms of lost economic activity is $153 million.

-

Over a decade, the income and economic activity lost to the city from the large number of dropouts in the 2004 cohort rises to $2.4 billion, and over a 30-year career approximately $7.2 billion.

Clearly, there is a powerful economic argument for increasing the number of students who graduate from community colleges in New York. In fact, we found that even a small increase in New York’s community college graduate rates would have massive benefits, not only for individuals and employers, but for taxpayers and the city’s economy.

We calculated the value of increasing community college graduates rates in New York City by just 10 percentage points, from 28 percent to 38 percent, for the group of students who entered CUNY community colleges in fall 2004. This modest graduation rate increase:

-

Would have enabled the city, state and federal governments to spend at least $18.1 million on college graduates instead of college dropouts.

-

Would have added $30 million per year to the city economy in income and economic activity, even after discounting for the graduates who leave the city for other opportunities.

-

Would have brought in $2.7 million in additional tax receipts for one year.

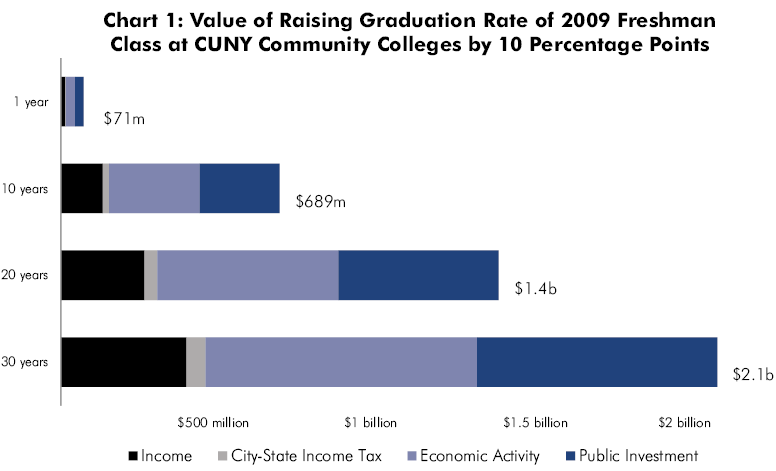

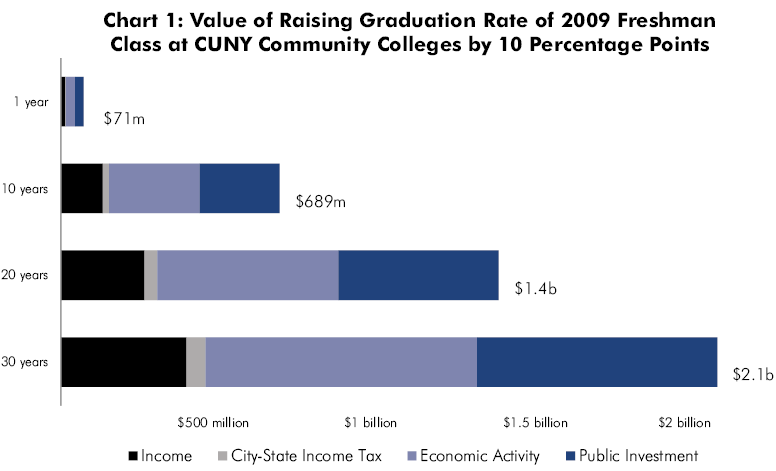

These calculations are based on increasing graduation rates from the cohort of students who entered CUNY community colleges in 2004. But looking ahead to the 2009 cohort, which has 50 percent more students enrolled than the 2004 group, one can readily see the immense economic benefit of increasing graduation rates. Raising the six year graduation rate at CUNY community colleges by 10 percentage points will increase the one-year earnings of the 2009 cohort by $16 million, and one year tax receipts by at least $3.9 million. Moreover, because earnings gained are spent at the grocery store, clothing store, and other fixtures of the local economy, the extra economic activity spurred by the one-year increase in income would add up to $28.5 million, a sum that would, in turn, lead to additional tax receipts for the city, state and federal governments. Finally, public investment worth more than $26 million in operational aid, Pell and TAP grants would be spent as intended—on college graduates.

Furthermore, all these savings compound over time. Over a 10-year period, the combined income, economic activity and public-investment value to New York City and New York State of raising the graduation rate by 10 percentage points would be roughly $689 million; over two decades, $1.4 billion; over a three-decade career, $2.1 billion.

It is tempting to regard the low graduation rates as a failure of the individual institutions, the teachers, administration or some combination. The reality, however, is that low graduation rates are a chronic problem around the country. They cannot be separated from other dilemmas our nation faces: low high school graduation rates, weak college preparation among those who do obtain their high school diplomas, economic dislocations that drive many adults back to school for retraining, and state and local budgets that lag far behind the fiscal needs of the institutions on the frontlines of postsecondary learning. In New York City, for instance, only a quarter of students who enter a public high school are ready for college after four years; the college readiness rate was actually less than half the graduation rate at 299 of the city’s 363 schools.

CUNY’s community colleges provide a unique service by offering a shot at higher education to New Yorkers who have few other options for postsecondary study. Three-quarters of all entering freshmen test into developmental education courses. According to a survey administered to entering freshmen, almost half are the first individuals in their families to attend college, and almost half live in a family with a household income below $20,000.

The good news is that CUNY is now aggressively tackling the problem. In the last few years, CUNY leaders have articulated clear graduation rate goals, launched its first new community college in 40 years in a way that could drive systemic reform, implemented several system-wide student success initiatives, and encouraged equally bold reform efforts at several campuses. These new initiatives—including the Accelerated Study in Associate Programs (ASAP), CUNY START, Graduate NYC, the Latino STEM Support Network Early Alert System at Queensborough Community College, and early college high schools like the new Pathways in Technology (P-Tech) Early College High School in Brooklyn—have already demonstrated that it is possible to move the needle.

In a 2008 interview, Chancellor Matthew Goldstein told us that it is critical for CUNY and other community college systems to graduate more of their students, even while acknowledging legitimate reasons for the low graduation rates. “Many students come in very poorly prepared, so we have to remediate them with work that is not college work. That can take a year or a year and a half. Also, the students are often poor. Many have to work while they are going to school, and that’s a serious issue. And they are not well funded, so we can’t give a wide spectrum of courses over a wide number of hours during the day. You put all of that stuff together and it adds up. And then there are students who go to community colleges without the intention of getting a degree,” says Goldstein. “Those are all legitimate reasons why graduation rates are low. But that is not going to succeed in convincing the market place that these are serious places that deserve investment. If we get graduation rates up, community colleges are going to be viewed in a very different way. So we have to get graduation rates up.”

This is an excerpt. Click here to read the full report (PDF).