New York City’s economy has been on an unprecedented roll over the past two decades. There are nearly a million more jobs across the five boroughs today than in 1997, and the city’s unemployment rate now stands at less than half of what it was then.1 This extraordinary economic transformation was fueled by a number of factors, including the plunging crime rate and the tech sector’s meteoric rise. But few things have been more important to the city’s extended economic boom—or more overlooked—than the record increase in tourists.

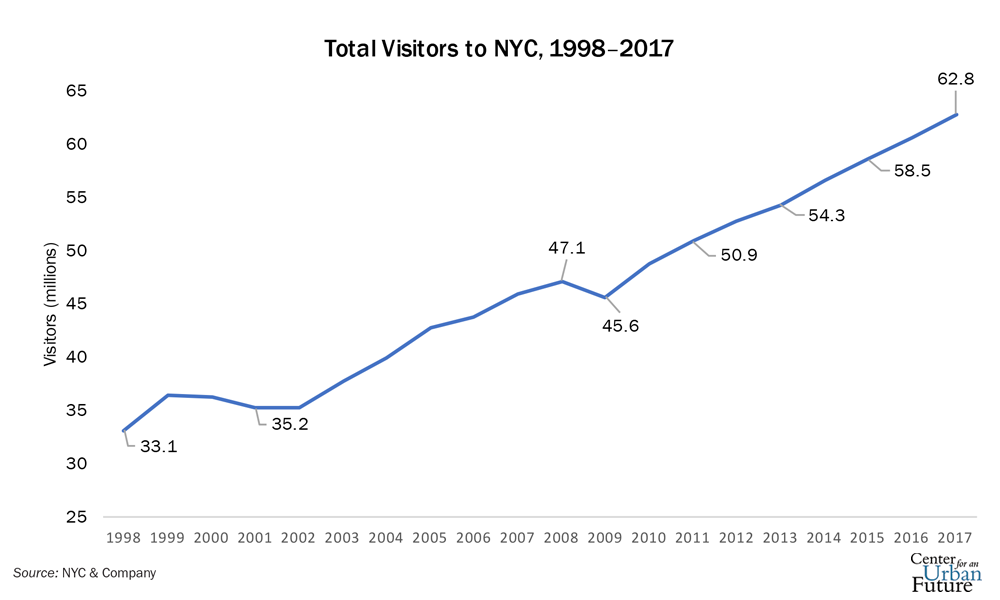

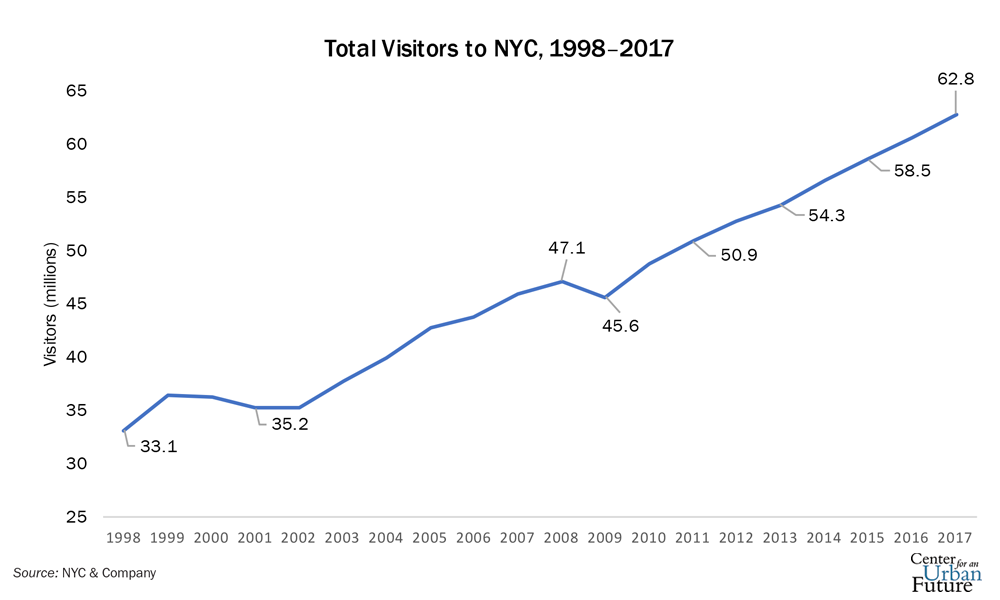

Twenty years ago, around 33 million tourists visited New York City each year. These days, the city routinely tops 60 million annual visitors.2 In 2017 the city hit a record high of 62.8 million visitors.3

This remarkable surge in tourism has done more than merely clog sidewalks in Times Square. It has sparked hundreds of thousands of new jobs—not just at hotels, but in restaurants, retail shops, museums, airports, tour bus companies, and even travel tech start-ups. In the process, tourism has been elevated from a fairly important part of the city’s economy to one of the four leading drivers of job creation in New York. Indeed, tourism now accounts for about as many jobs as the city’s tech sector, the creative economy, or the finance industry

Tourism has also become an increasingly vital source of new middle-income jobs. As just one example, the city is now home to nearly as many accommodations jobs, which pay $62,000 per year on average, as jobs in manufacturing, which pay an average of $58,000.4 To be sure, many of the jobs in the sector offer relatively low wages, at least to start. But tens of thousands of tourism positions provide critical entry points into the labor force for a highly diverse range of New Yorkers. Indeed, no other sector offers as many accessible jobs, with 91 percent of tourism jobs open to workers with less than a bachelor’s degree.5 The tourism sector also reflects the diversity of the city. More than 65 percent of New York City residents who work in tourism-related industries are people of color and 54 percent are immigrants, compared to 59 percent and 44 percent, respectively, of workers in other sectors.6

Despite the increasing importance of tourism to the city’s economic future, our research suggests that New York’s tourism sector faces several new and evolving challenges—from the strong dollar and the effect of international travel restrictions to air traffic congestion and the city’s aging transportation infrastructure—that could cause reductions in tourism and a decline in jobs. It’s also an industry full of opportunity. Although some industries in New York could be displaced by automation in the decade ahead, global tourism is expected to grow even further as more than a billion people around the world join the middle class.

But taking advantage of these opportunities—and addressing the growing number of threats— will require a new level of planning from city and state government.

This report captures the far-reaching impact of tourism on the city’s economy, details the challenges threatening the sector’s continued vitality, and advances ideas to cultivate and sustain New York’s tourism boom in the years ahead. Funded by the Association for a Better New York and Times Square Alliance, the study draws from an extensive analysis of economic and census data as well as interviews with more than 60 policymakers, business executives, and tourism professionals from across New York City. In addition, researchers at the Center for an Urban Future spoke with more than 100 owners and workers at businesses across all five boroughs—including restaurants, retailers, hotels, tour companies, and even travel-focused tech startups—in order to better understand the effects of tourism on every corner of the city and its economy, and the challenges facing tourism in the years ahead.

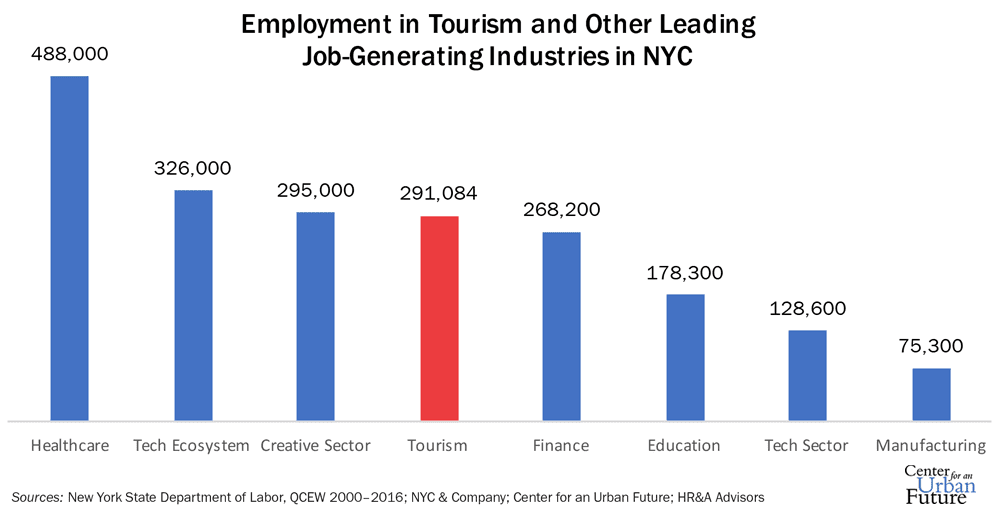

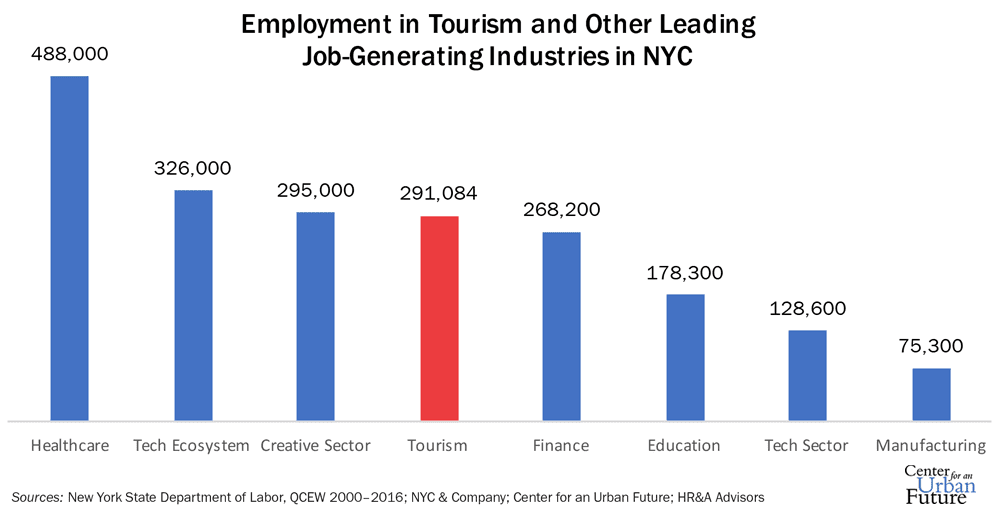

According to Tourism Economics, the firm that produces tourism figures and analysis for NYC & Company, the tourism and hospitality sector directly employs 291,084 people in the five boroughs—about one out of every eleven workers in the city.7 That puts tourism in the same league as the biggest industries in New York City.

While healthcare is by far the city’s largest industry, employing 488,000 New Yorkers, tourism and hospitality now directly employs more New Yorkers than the finance sector (268,200 jobs). Tourism also has more than twice as many jobs as the city’s tech sector (128,600 jobs) and nearly as many as the broader tech ecosystem (326,000). It greatly outnumbers jobs in the education sector (178,300), has more than four times as many jobs as manufacturing (75,300), and employs roughly the same number of people as the city’s creative economy (295,000), which includes nine creative industries—from advertising and architecture to film/ television production and performing arts.8

Jobs that are fueled by tourism have grown faster than the city’s overall economy in recent years. From 2009 to 2016, direct tourism jobs increased 27 percent, from 228,948 to 291,084, compared to 20 percent overall job growth.9 In several of the industries that have benefited from the tourism boom, job growth has been even more significant.

Due to changes in how Tourism Economics gathers its data made roughly a decade ago, it’s not possible to contrast the sector’s growth before 2009 with that of the broader city economy. However, our analysis of data from the New York State Department of Labor shows that employment in the accommodations sector alone has expanded by 46 percent from 1997 to 2017.

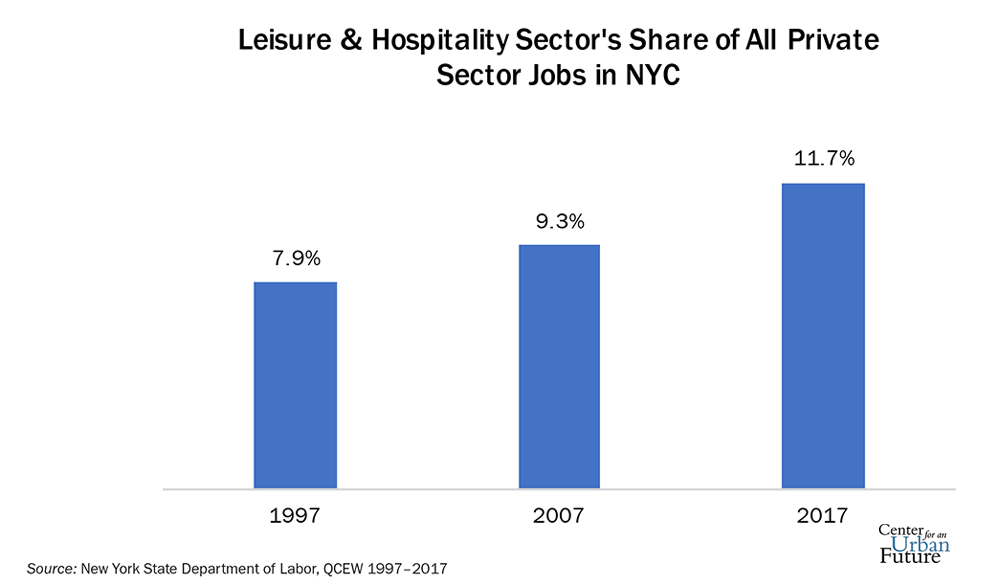

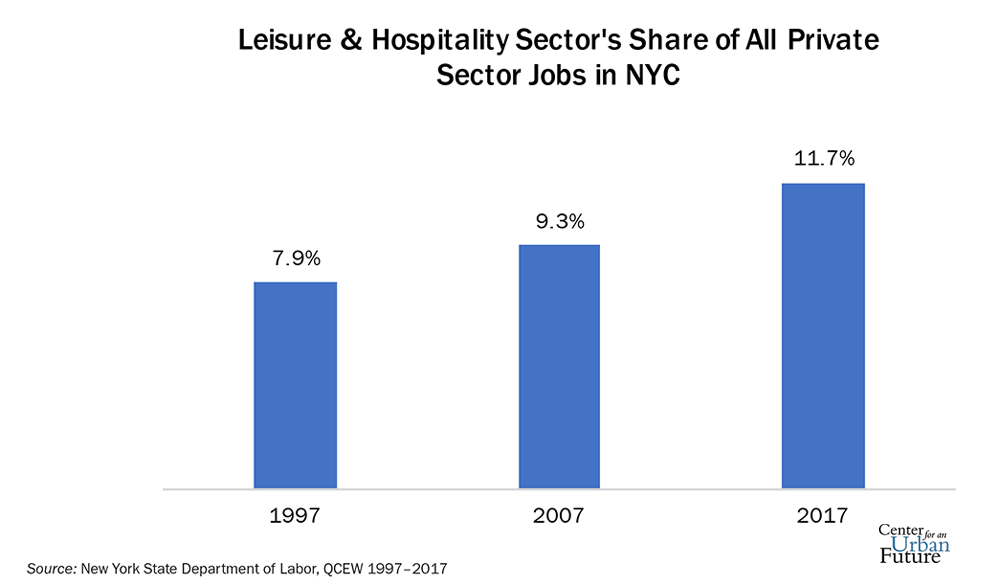

During the same period, employment in the city’s “leisure and hospitality” sector—which includes hotels, restaurants, arts, and entertainment—increased by a remarkable 98 percent, going from 227,900 jobs in 1997 to 452,100 in 2017. 10

While the majority of tourism jobs are based in the Manhattan neighborhoods that are home to a disproportionate share of the city’s tourism infrastructure, the fastest employment growth is occurring in the other four boroughs. Since 2000, Brooklyn added 1,294 accommodations jobs (a 198 percent increase) while Queens added 876 (37 percent). Staten Island added 279 jobs (317 percent), and the Bronx added 161 jobs (52 percent). Manhattan, meanwhile, added 9,515 accommodations jobs, a 27 percent gain. Moreover, 81 percent of the New York City residents who are employed at hotels live in the four boroughs outside Manhattan. Queens is home to 14,750 hotel workers, followed by Brooklyn (10,986), Manhattan (8,324), the Bronx (6,881), and Staten Island (1,819).11

Boosting key sectors of New York City’s economy

The full impact of tourism on New York’s economy is best seen by its reach. Most New Yorkers understand that tourism leads to job creation at hotels, theme restaurants like Bubba Gump Shrimp Co., and attractions such as Madame Tussauds wax museum. But this report documents that tourism has also been responsible for a significant portion of the job creation in many of the city’s fastest-growing industries, including restaurants and bars (which added 142,000 jobs since 2000), retail (which had a net gain of 71,000 jobs), and arts, entertainment, and recreation (which grew by 30,000 jobs).12

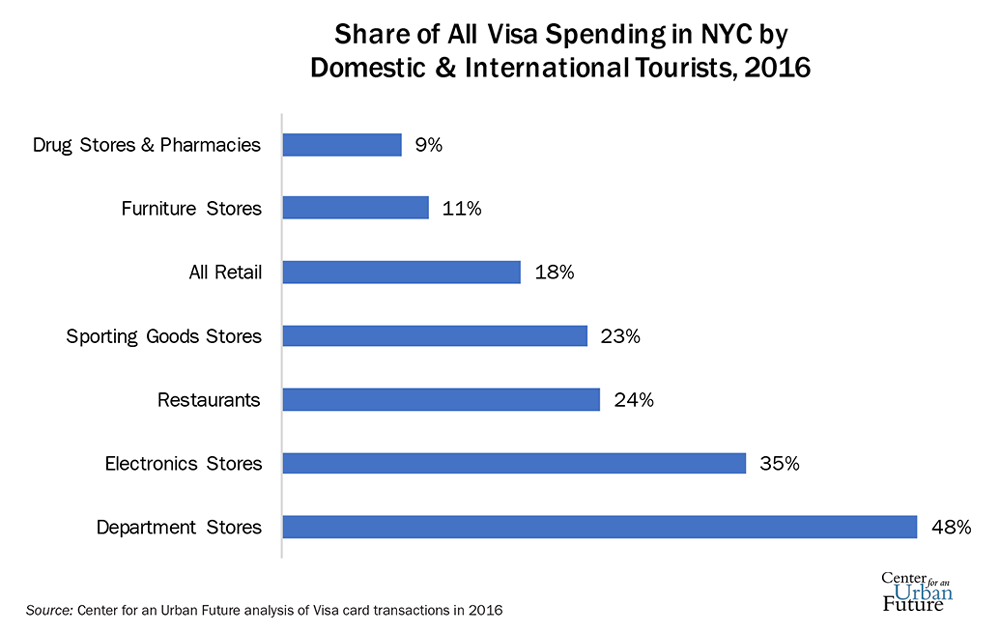

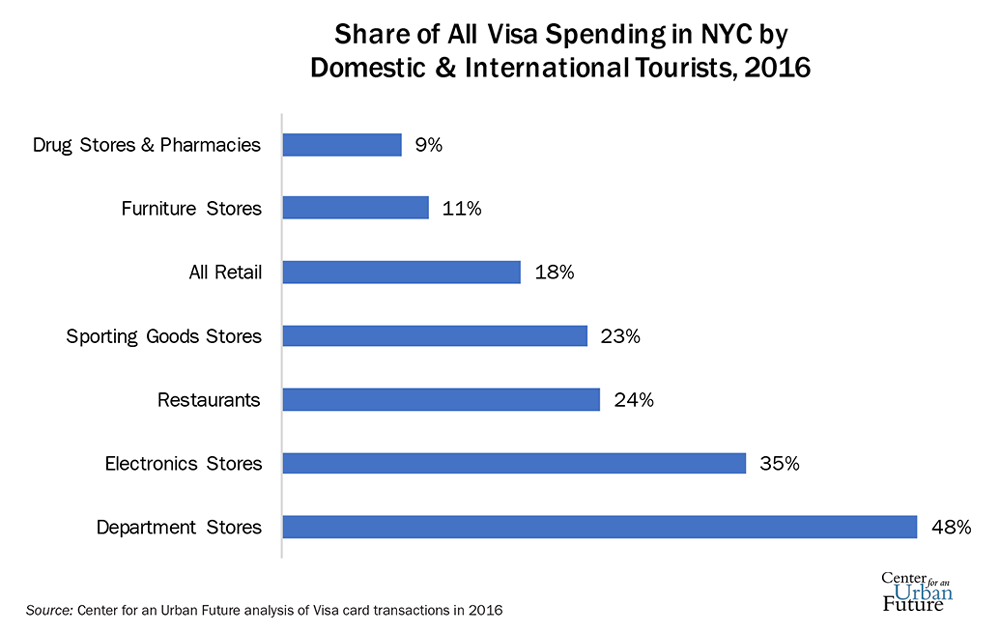

For instance, the number of jobs in restaurants and bars has exploded over the past two decades, with employment increasing 91 percent since 2000.13 Although a healthy share of this growth is attributable to the city’s increasing population and rising incomes, our analysis shows that nearly half the gains could stem from tourist demand. Domestic and international tourists are responsible for 24 percent of all sales at New York City restaurants and drinking places, according to our analysis of Visa credit card transactions made by people coming from outside of the New York City Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA).14 Many restaurateurs we interviewed across the city—not just in Times Square—report that more than half of their customers are tourists—in some cases, upward of 90 percent. In 2016, tourists spent $9.1 billion at food and drinking establishments, up 35 percent since 2009, after adjusting for inflation.15

“Without a doubt tourism has fueled our restaurants, and that has allowed us to employ more people,” says John Meadow, president of LDV Hospitality, which owns several restaurants and bars downtown, including Scarpetta, Lugo, and The Lately. “I can’t stress enough how tourist volume helps maintain topline revenues in the face of the increasing expenses of running a restaurant in New York City. In the restaurant business we say that volume heals all wounds.”

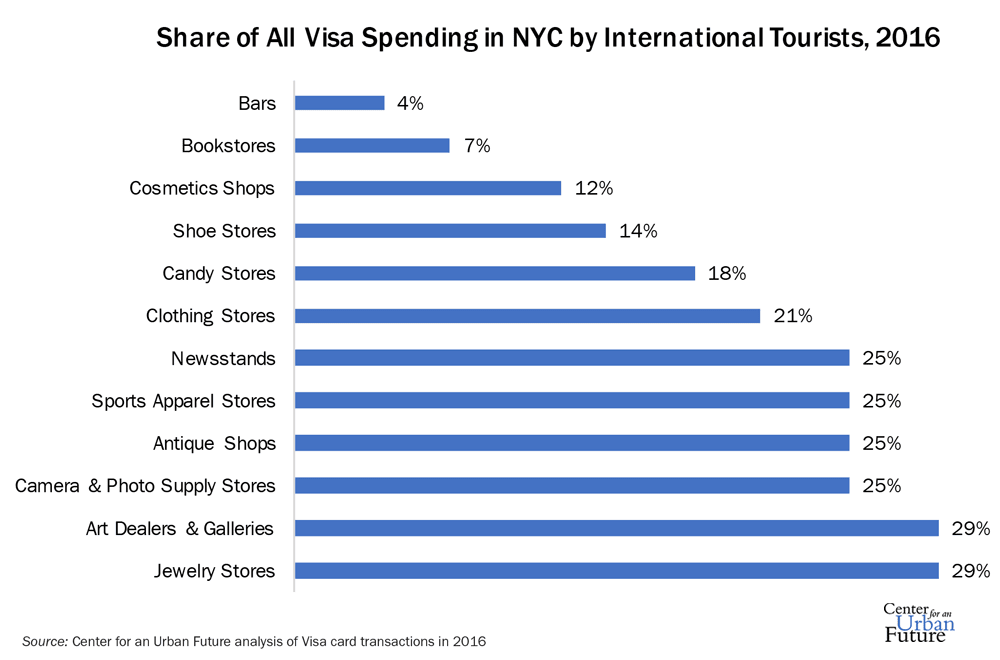

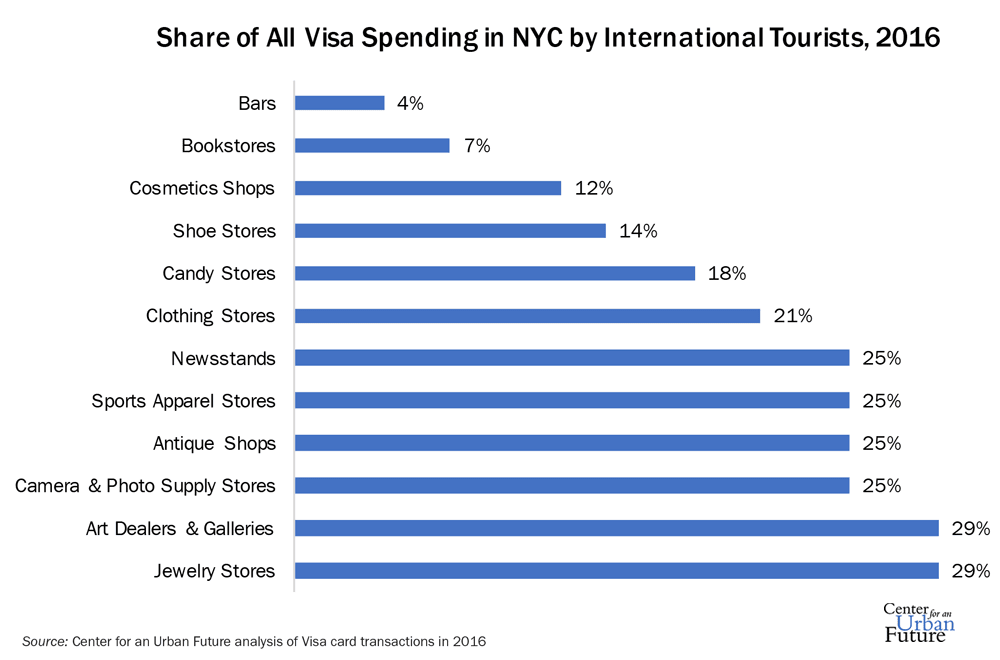

Tourists have also been a huge contributor to the growth of the city’s retail sector, which has added nearly 71,000 jobs since the year 2000.16 Tourists account for nearly one-fifth of all Visa credit card purchases at the city’s retail stores.17 Across many parts of the city, the impact of tourists on retail is even larger. In our interviews with more than 100 retail store owners and managers in popular shopping corridors from SoHo and lower Fifth Avenue to Williamsburg and Dumbo, the average retailer told us that tourists account for 30 to 40 percent of all customers. “I’d say that 42 to 43 percent of the growth in retail is due to tourists,” says Faith Hope Consolo, chair of the retail division at Douglas Elliman Real Estate. Tourists, on average, devote 20 percent of their budgets to shopping.18 International tourists, especially, tend to make big purchases, stocking up on things they can’t find at home or which cost significantly more, from designer suits at Bloomingdale’s to iPhones at the Apple Store or diamond rings at Tiffany. Indeed, within the retail sector, job growth has been strongest in many of the categories that are most popular with tourists.19 Our research shows that tourists account for 48 percent of the credit card spending at the city’s large department stores and 35 percent of spending at electronics stores.20 International tourists alone are responsible for 29 percent of sales at the city’s jewelry stores. They also account for a significant share of spending at art dealers and galleries (29 percent), camera and photo supply stores (28 percent), clothing stores (21 percent), antique shops (25 percent), candy stores (18 percent), shoe stores (14 percent), sporting goods stores (12 percent), and cosmetics shops (12 percent). All this spending has created jobs. For instance, while retail jobs have grown by 26 percent overall, jobs in “general merchandise” stores, of which department stores are the major subcategory, have increased 39 percent—adding almost 12,000 jobs.21

In recent years, tourism has begun to play another critical role: a dependable source of sales at a time when many retailers are facing increasing pressures from online retailers. In the face of these headwinds, many retailers say that the city’s tourists have made up the difference and even allowed for further growth in categories such as fashion, electronics, cosmetics, and luxury goods.

Tourists are driving significant growth in attendance at many of the city’s marquee cultural institutions, which has in turn fueled significant employment gains. The city’s museums and historical sites have added more than 4,400 jobs since 2002—an 86 percent increase.22 Many of these new jobs would not have been created if not for sharp increases in visitation from tourists. In fact, tourists now comprise 73 percent of visitors to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), 70 percent of visitors to the Whitney Museum of American Art, and 60 percent of the Metropolitan Museum’s visitors, providing a vital source of ticket revenue.

Museums report adding more docents, retail and restaurant workers, coat check attendants, and security guards to help them with the increasing numbers of visitors. For instance, the Whitney has hired as many as 100 full-time equivalent positions due to the museum’s skyrocketing tourist visitation since moving downtown. Museum officials and festival directors also say that support from tourists strengthens their ability to fulfill their core missions of presenting, preserving, and promoting art and talent.

Likewise, tourism has fueled job growth on Broadway, where out-of-towners now comprise 61 percent of the audience. The 41 Broadway theaters alone have added more than 2,300 jobs since 2009, and currently employ more than 12,500 people.23

Tourists also support other key parts of the city’s entertainment scene. Visitors from outside the metropolitan area are responsible for 40 percent of all sales at the city’s theaters, orchestras, professional sports venues, video game arcades, aquariums, and attractions.24 Thanks in part to the increase in tourists, employment in performing arts venues and sports arenas has increased 29 percent since 2000, adding more than 8,900 jobs.25

The explosion in tourists has also spurred the development of new tourist attractions, which have led to several hundred new jobs. In the past five years alone, the city has added the NFL Experience Times Square, National Geographic Encounter, Gulliver’s Gate, the Oculus at the World Trade Center, and the One World Observatory, among others. National Geographic Encounter, which opened last year in Times Square, employs 141 people—two out of three of whom work in guest services, retail, or cleaning.26 Gulliver’s Gate, which also opened last year, employs 50 people, including executives, artists, and designers, as well as hospitality and retail positions.27 Other tourist attractions have expanded thanks to the increase in tourists. For instance, Top of the Rock, the popular observatory at Rockefeller Center, employs 205 people, up from 120 in 2006.28

The city’s tourism boom has also spurred job growth in the transportation sector. In particular, employment in the city’s scenic and sightseeing transportation industry has increased by 90 percent since 2000—by far the fastest-growing segment of the transportation sector. More than 2,200 people now work in this slice of the transportation economy—which includes jobs on tour buses and sightseeing boats—up from 1,200 in 2000.29

Tourism has even led to more jobs in the tech sector, with New York emerging as a leading hub for travel-tech companies in recent years. Of Travel + Leisure’s “50 Best New Travel Apps for 2017,” nine were developed by companies based in New York.30 New York is home to dozens of new travel-tech ventures, ranging from a room service delivery app to an app that alerts travelers about the length of waits at airport security lines. Other tech companies such as SevenRooms, which manages customer data for hospitality and food service establishments, are expanding to meet the tourism-related demand.

As the number of annual tourists to New York has skyrocketed over the past two decades, so has passenger traffic—and jobs—at the city’s airports. The total number of passengers traveling through JFK increased by 89 percent over the past 20 years, from 31.2 million in 1997 to 58.9 million in 2016. At JFK, the number of international passengers alone jumped by 14.3 million passengers during this time. Passenger traffic also increased by 38 percent at LaGuardia (from 21.6 million to 29.8 million) and by 30 percent at Newark Airport (from 30.9 million to 40.5 million).31 This has sparked significant employment gains. New York’s three major airports employed 75,465 people in 2016, an increase of 16,565 jobs since 2002. With tourists accounting for 72 percent of passengers at JFK and 50 percent at LaGuardia, visitors from outside New York City are driving this job growth.32

A vital source of both well-paying and accessible jobs

Jobs in the tourism and hospitality sector are often dismissed as low-paying positions. But tourism has become an increasingly important source of middle class jobs that are accessible to a broad array of New Yorkers.

For instance, the city is now home to more than 51,000 hotel jobs. These jobs have similarly modest educational requirements as those in the city’s manufacturing industry, while paying even better—an average annual income of $61,756 for hotel jobs compared to $57,807 in manufacturing. Although there are still more jobs overall in manufacturing—75,000, as of 2016—the accommodations sector has been rapidly closing the gap. Since 2000, the city has added more than 12,000 hotel jobs and lost nearly 97,000 manufacturing jobs.33

Crucially, middle-class tourism-related jobs are growing at a time when many traditional sources of Source: New York State Department of Labor, QCEW 1997–2017 8 Center for an Urban Future accessible, well-paying jobs are stagnating or in decline. For example, over the next decade, accommodations jobs are expected to grow by 29 percent while manufacturing jobs are projected to decline by 5 percent and wholesale trade jobs are set to grow by just 2.6 percent.34 Overall, our analysis finds that over the next decade the industries supported by tourism are projected to create more than 48,000 jobs that pay at least $40,000 per year with experience—more than any other sector in New York.35

Additionally, in many tourism-related industries, jobs pay more than their non-tourism-related counterparts. Tourism-related food and beverage jobs pay an average of $40,000, compared to $27,000 citywide, and tourism-related retail jobs pay 24 percent more, on average. Workers in many low-wage positions, including dishwashers and housekeepers, are paid at least twice as much if they work in accommodations compared to other industries.36 For instance, dishwashers in union hotels earn $32 per hour, while dishwashers in New York City overall earn little more than minimum wage.37

Industries supported by tourism also provide a large and growing supply of accessible jobs for a diverse cross-section of New Yorkers. Out of the 43 tourism-related occupations that are adding jobs in New York City, 39 of them require fewer than five years of experience and are accessible to people who have less than a bachelor’s degree.38 Fully 66 percent of workers in tourism-related industries have less than a bachelor’s degree, compared to 50 percent of workers in non-tourism related industries.39

“The jobs in this sector are both an entry point, particularly for immigrants, and an important pathway to good, middle-class jobs,” says Jeffrey Stewart, cofounder of Walnut Hill Media and a former executive at Loews Hotels. “There are great advancement opportunities in hospitality. The industry is filled with people who went from an entry-level clerk job to become a high-level manager.”

Tourism jobs are particularly accessible to young adults with little experience who are looking for entry into the labor force. More than one-third (36 percent) of all workers in the industries fueled by tourism, such as leisure and hospitality, are between the ages of 16 and 29, compared to just 23 percent of workers in industries unrelated to tourism.40 These accessible jobs are critically important at a time when automation is threatening entry-level work and traditional sources of employment for workers with limited educational attainment, such as manufacturing, are shrinking.

In addition, tourism offers crucial footholds into the job market for a particularly diverse range of New Yorkers. A significant share of wages in the industries fueled by tourism go to immigrants, people with less formal education, people of color, and residents of the five boroughs, ensuring that this wealth is spread more equitably across the city’s communities. More than 65 percent of New York City residents who work in these tourism-fueled industries are people of color, and 54 percent are immigrants. 41 The only industries in the city with higher shares are healthcare and construction, respectively. Likewise, nearly nine out of ten workers in tourism-related jobs live in the five boroughs, making it more likely that earnings from tourism will support local communities through induced spending. By comparison, just 59 percent of New York City’s finance and insurance workers live within the city limits.42 “It’s one of the great gateway industries for immigrants,” says Mitchell L. Moss, professor of urban policy and planning at NYU Wagner. “Even if you don’t know English, there are a lot of career paths.”

Sustaining the boom

With record numbers of visitors and a thriving tourism economy, it may appear that New York City’s tourism industry has nowhere to go but up. But several emerging challenges may already be slowing tourism growth, with far-reaching effects across the city’s economy. Left unaddressed, these threats could limit the city’s ability to attract visitors in an increasingly competitive environment and restrict the future growth potential of tourism jobs.

The challenges begin on arrival at the city’s airports, which often results in an unpleasant and exhausting visitor experience. Frequent flight delays and airport overcrowding, inadequate amenities, and poor transit connections are common sources of frustration. These shortcomings hurt New York City’s competitiveness, especially by comparison to other global hubs— and even U.S. regional airports—that can offer fast, free WiFi; more efficient processing through customs; clearer wayfinding through terminals; and seamless connections to public transit. In addition, a severe lack of capacity for more takeoffs and landings will sharply curtail future growth unless New York’s congressional leaders get behind a plan to adequately fund long-delayed air traffic control modernization efforts.

Likewise, rampant subway delays and consistently overcrowded trains are not only hurting the daily commutes of New Yorkers; these transit deficiencies have begun to affect tourists’ perceptions of New York, according to numerous interviews. At the same time, a lack of planning around the needs of a city with 60 million or more annual visitors is revealing major strains, including midtown gridlock exacerbated by a lack of tour bus parking and overcrowded sidewalks from Herald Square to SoHo.

There are also challenges stemming from issues outside the city’s policy purview. Although international tourism to New York hit a new record high this year, other data shows signs of a possible future decline. For instance, several international surveys of public opinion point to an increase in negative perceptions of the United States abroad following the 2016 election of Donald Trump, and prospective visitors report a decrease in the likelihood that they will plan future trips to the United States. The strength of the U.S. dollar is also likely to discourage some international tourists— especially visitors from the United Kingdom and the eurozone—who have seen their buying power drop as their currencies lose ground against the dollar.

Amid these emerging threats, New York also has an opportunity to capture a more diverse share of the growing tourism market as the global middle class experiences unprecedented expansion. But the world isn’t standing still. The tourism industry faces greater competition than ever before, including from more affordable destinations in Latin America and Asia, increasingly popular North American cities like Toronto and Miami, and cities that have invested much more in developing a welcoming visitor experience. After two decades of sustained growth, New York will have to do more to maintain the vitality of its tourism industry in the years ahead.

“We cannot take tourists for granted, and must deliver on great guest experience for the price that is being paid,” says Keith Douglas, managing director of One World Observatory.

The good news is that New York boasts one of the most well-regarded tourism promotion agencies in the world, NYC & Company. Although Mayor de Blasio has increased NYC & Company’s public funding—from $12.3 million in 2014 to $21.5 million today—the organization’s overall budget of $38.6 million has not stayed competitive with that of tourism promotion agencies in other global destinations.43 Several major destinations spend much more than New York, including Los Angeles ($49.7 million), Barcelona ($78 million), and Shanghai ($210.8 million). Likewise, many other U.S. cities are investing more per resident, including Denver, Chicago, and Portland.44 For example, Denver spends nearly $40 per resident on tourism promotion.

In New York City, that figure is less than $4.50. With potential headwinds threatening to slow tourism’s growth, NYC & Company will need more resources to fulfill its important role in an increasingly competitive environment.

In the years ahead, New York City can do much more to connect tourism to its broader economic development strategies, sustain the current number of annual tourists while taking advantage of new opportunities, and grow this crucial source of middle-class jobs. Doing so will require comprehensive strategic planning for the future of the industry and sustained investment in a variety of critical infrastructure needs, as well as a sharper focus on the skills needed for employment in the tourism workforce.

At a time when automation is threatening to displace entry-level jobs across multiple industries and traditional sources of good, accessible jobs like manufacturing are on the decline, New York City needs to sustain and grow the thousands of good jobs that tourism is creating, and ensure the benefits are spread widely across the city.

In addition to policies and strategies that can support the sustainable growth of the tourism economy, New York needs to take some preventive actions to help mitigate problems that stem from increased tourist visitation, ensuring that New Yorkers will continue to see the widespread benefits that tourism brings. Failing to mitigate the ill effects of tourism—including crowding in and around major attractions, inadequately planned hotel development, and the proliferation of tour buses—could also threaten to turn New Yorkers against tourists. Such a backlash is being felt in major tourist destinations around the world, including Amsterdam, Iceland, and in Barcelona, where the current mayor was elected on an anti-tourism platform.

This report concludes with 25 achievable policy recommendations that can help New York continue to grow a sustainable tourism economy while confronting its looming challenges. By investing in a healthy tourism ecosystem, New York can continue to benefit from this essential source of good and accessible jobs while strengthening its fourth-largest sector for the long term.

1. New York State Department of Labor, Current Employment Statistics (CES), https://www.labor. ny.gov/stats/nyc.

2. NYC & Company, “NYC Travel and Tourism Visitation Statistics,” http://www.nycandcompany.org/ research/nyc-statistics-page.

3. James Barron, “Tough Talk in Washington Did Not Keep Tourists Away from New York in 2017,” New York Times, March 20, 2018, https://www.nytimes. com/2018/03/20/nyregion/nyc-tourism.html.

4. New York State Department of Labor, Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) 2000– 2016, https://www.labor.ny.gov/stats/lsqcew.shtm.

5. Long-Term Occupational Projections, 2014-2024, New York State Department of Labor, https://www. labor.ny.gov/stats/lsproj.shtm.

6. U.S. Census, Current Population Survey, 2016. Tabulated using IPUMS.

7. Data provided by NYC & Company/Tourism Economics to the Center for an Urban Future. In addition to 291,084 direct jobs, tourism creates an additional 42,400 indirect jobs at firms that supply tourism enterprises, such as food manufacturers and distributors, hotel linen laundry services, and others. The sector also induces 49,901 jobs across the city through the $16.5 billion in wages paid to tourism workers. The jobs induced are in grocery stores, shops, and other neighborhood businesses, as well as healthcare and education. New Yorkers holding those indirect and induced jobs earn an additional $8.2 billion in wages. 8. Healthcare, finance, educationand manufacturing jobs figures from New York State Department of Labor, QCEW, 2000–2016. Tourism jobs figure from data provided by NYC & Company/Tourism Economics to the Center for an Urban Future. Creative economy figure from Creative New York, Center for an Urban Future, https://nycfuture.org/research/ creative-new-york-2015. Tech sector job figure from Office of the New York State Comptroller, The Technology Sector in New York City, https://www.osc. state.ny.us/osdc/rpt4-2018.pdf. Tech ecosystem figure from HR&A Advisors, 2016 NYC Tech Ecosystem, http://abny.org/images/downloads/2016_ nyc_tech_ecosystem_10.17.2017_final_.pdf.

9. New York State Department of Labor, QCEW, 2000– 2016, and data provided by NYC & Company/Tourism Economics to the Center for an Urban Future. 10. New York State Department of Labor, CES.

11. U.S. Census, American Community Survey, 2016. Tabulated using IPUMS.

12. New York State Department of Labor, QCEW, 2000–2016.

13. Tourist share of restaurant spending from analysis of Visa credit card transactions in 2016. Jobs number from New York State Department of Labor, QCEW, 2000–2016.

14. Ibid.

15. Data provided by NYC & Company to the Center for an Urban Future.

16. New York State Department of Labor, QCEW, 2000–2016.

17. Analysis of Visa credit card transactions in 2016. Domestic and international tourists account for 20 percent of retail spending.

18. Total spending share from analysis of Visa credit card transactions in 2016.Share of budget spent on shopping from data provided by NYC & Company/ Tourism Economics to the Center for an Urban Future.

19. New York State Department of Labor, QCEW, 2000–2016.

20. Analysis of Visa credit card transactions in 2016.

21. New York State Department of Labor, QCEW, 2000–2016.

22. New York State Department of Labor, QCEW, 2000–2016.

23. Data provided by The Broadway League to the Center for an Urban Future.

24. Analysis of Visa credit card transactions in 2016.

25. New York State Department of Labor, QCEW, 2000–2016.

26. Interview with Shannon Hebert, head of marketing and sales, National Geographic Encounter.

27. Interview with Jason Hackett, director of marketing, Gulliver’s Gate.

28. Interview with Paul Ortega, national director of training and organizational development, Swiss Post Solutions Inc.

29. New York State Department of Labor, QCEW, 2000–2016.

30. Christopher Tkaczyk and Shivani Vora, “The 50 Best New Travel Apps for 2017,” Travel + Leisure, January 19, 2017, http://www.travelandleisure. com/travel-tips/mobile-apps/best-new-travel-apps.

31. Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, Airport Traffic Report, 1998 and 2016, https://www. panynj.gov/airports/pdf-traffic/airtraffic1998.pdf and https://www.panynj.gov/airports/pdf-traffic/ ATR2016.pdf.

32. Ibid.

33. New York State Department of Labor, QCEW, 2000–2016.

34. New York State Department of Labor, 2014–2024 Statewide and Regional Long-Term Industry Projections. Accessed at https://www.labor.ny.gov/stats/lsproj.shtm.

35. Ibid.

36. Union wages from Collective Bargaining Agreement Between the Hotel Association of New York City, Inc. and the New York Hotel and Motel Trades Council, AFL-CIO, effective from July 1,2012 to June 30, 2019. Overall wage figures from Long-Term Occupational Projections, 2014–2024, New York State Department of Labor, https://www.labor.ny.gov/ stats/lsproj.shtm.

37. Overall wage figures from New York State Department of Labor, Long-Term Occupational Projections, 2014–2024.

38. New York State Department of Labor, Long-Term Occupational Projections, 2014–2024. Our analysis of tourism-related industries includes those industries where tourism is driving a significant share of the growth, including accommodations, food service, retail, transportation, and arts and entertainment.

39. U.S. Census, Current Population Survey, 2016. Tabulated using IPUMS.

40. Ibid.

41. Ibid.

42. U.S. Census, American Community Survey, 2012– 2016 5-year sample. Tabulated using IPUMS.

43. NYC & Company.

44. See page 36 for a complete summary of other cities’ tourism promotion budgets.

Photo Credit: Matt A.V. Chaban