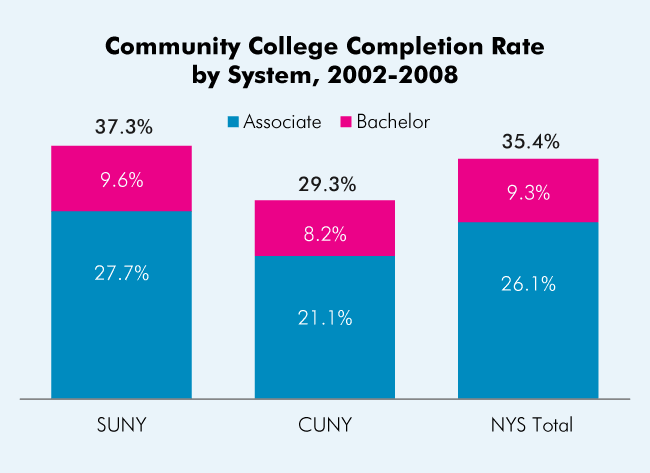

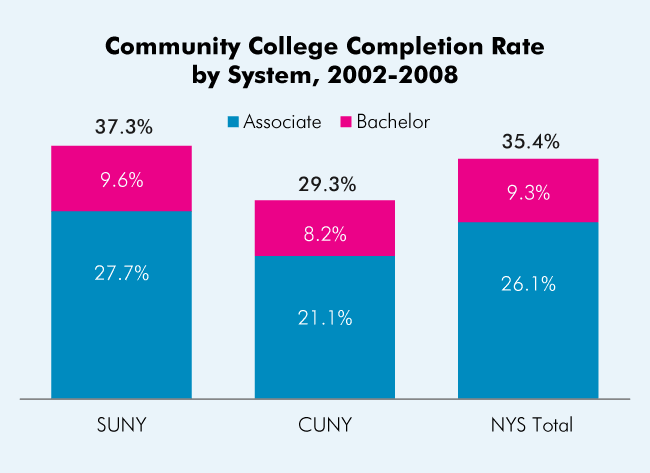

CUNY and SUNY community colleges are already meeting many local employment needs, but with hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers in low-wage jobs, at the same time that many employers are complaining about their inability to find suitably skilled job applicants, the need to graduate more community college students is obvious. Our analysis finds that of the 42,000 students who enrolled at community colleges statewide in 2002, only 15,000 graduated six years later with a degree, 26 percent with an associate degree and 9 percent with a bachelor’s degree. Five percent were still enrolled, and the other 60 percent had either dropped out or transferred out of the system where their outcomes could not be tracked.

Outcomes at SUNY community colleges were substantially better than at CUNY. The average graduation rate at SUNY institutions was 37 percent, compared to 29 percent at CUNY. The two systems were fairly similar in connecting students to four-year colleges where they could earn bachelor’s degrees, but SUNY was about 30 percent more effective in graduating students with associate degrees.

|

Table 1: NYS Community Colleges with the Highest and Lowest Graduation Rates |

|---|

|

|

Avg Grad Rate |

Avg Pop |

Avg Low-Income |

Avg Minority |

Avg Remedial |

Avg Adult |

Top 5 schools

by graduation rate |

45% |

722 |

38% |

19% |

52% |

33% |

Bottom 5 schools

by graduation rate |

24% |

1,248 |

54% |

80% |

65% |

39% |

Individually, the top and bottom performing schools seemed to diverge in a number of important ways. The top five community colleges in the cohort—Jefferson, Niagara County, Finger Lakes, Jamestown and Cayuga—had an average graduation rate of 45 percent, while the bottom five—Borough of Manhattan, Westchester, Bronx, Sullivan and Hostos—had an average rate of just 24 percent. As Table 1 shows, the top performing schools had smaller student bodies on average and were all located in upstate regions, while the bottom performing schools were larger and were all located in downstate areas. To a striking degree, demographics and income level were both strong predictors of graduation success. The 2002 cohort at the top five schools consisted of 38 percent low-income students and 19 percent minority students. The bottom five schools had 54 percent low-income students and 80 percent minority students.

Statewide, the student bodies of the top performing schools tended to be overwhelmingly white, reflecting the demographics of their communities, and better off economically than those in lower-performing schools (though the vast majority of students even at these schools come from moderate income families). For example, the top five schools all had fewer than 30 percent minority students while the bottom five schools all had more than 50 percent. Out of 20 schools with above average graduation rates, none had a student body with more than a third minority students, and only five out of 20 had low-income student populations that were even close to 50 percent, namely Jamestown, Fulton-Montgomery, Herkimer, Mohawk Valley and Tompkins Cortland.

Colleges with low graduation rates were more likely to have a large share of entering freshmen placed into remedial courses. Interestingly, however, the reverse is not necessarily true: colleges with high graduation rates had an average share of remedial students, not a low share. In addition, colleges with higher graduation rates had a smaller share of adult students (defined here as ages 25-49), who are more likely to have work and family obligations than recent high school graduates.

Nationally, several other large states do a much better job of moving community college students toward graduation than New York. According to Complete College America, 39 percent of students at community colleges in New York either graduate with an associate degree or transfer to a four-year institution for a bachelor’s within three years of matriculating, compared to 52 percent of students in Florida, 50 percent in Wisconsin, and 48 percent in Illinois. Washington and Minnesota also do much better by this metric.

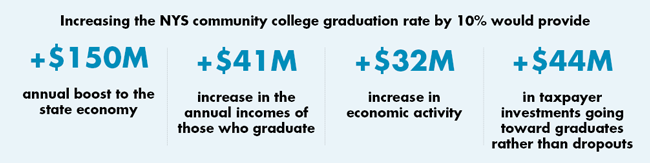

In addition to the economic costs, high dropout rates exact a large toll on the public purse. Considering both operating aid and student tuition assistance, we estimate that each community college dropout in New York costs the municipal, state and federal governments over $10,400. Overall, the dropouts in the 2002 cohort cost $260 million in taxpayer subsidies.

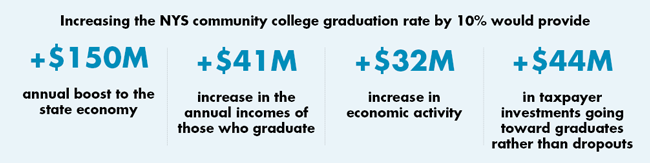

Thus, increasing the number of community college graduates even by just a little bit would provide significant material benefits to employers, individuals, local economies, and taxpayers. On the basis of the 2002 cohort, we calculate that the value of increasing graduation rates in New York State from 35 to 45 percent would result in:

-

$29 million more in increased annual earnings.

-

$23 million more in economic activity.

-

$6 million more in federal and state income tax receipts.

-

$44 million in tax payer contributions in the form of base operating aid, Pell and TAP Grants going towards community college graduates rather than dropouts.

-

4,205 more skilled and educated employees with credentials to fill local employer needs.

However, while the need to increase graduation rates at community colleges across the state is clear, there is no silver bullet. The causes of dropout are diverse, and strategies to keep students on track to graduation must not come at the cost of weakening academic rigor or compromising the open access mission. In addition, strategies to address student dropout must accommodate the autonomy of community colleges in the SUNY system. Unlike CUNY, SUNY’s twenty-nine community colleges are self-governed, and their presidents are appointed by local boards. SUNY is trying to create a more cohesive system for all of its institutions, but institutional autonomy will continue to be highly valued and defended.

Despite the diversity, community colleges across the state also face common drivers for dropout, even in very different communities. The lack of basic literacy and numeracy and preparation in Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) disciplines among entering students are major concerns across the state, but so are rising tuition costs and social issues. Many community college students are the first members of their family to attend college and are easily confused by its unfamiliar culture. Others struggle to balance the demands of work and family with their classes and study, and many older students need to brush up on subjects that have gathered dust since high school graduation.

Boosting student success at New York’s community colleges will not be simple or easy. But it can be done. We know this because it is happening in other states. Crucially, however, change will require New York State government to take ownership of the issue. The first step New York State needs to take is simply to acknowledge the problem, and forthrightly commit to solving it. The Governor, Legislature, and Board of Regents should publicly identify community college completion as a top state priority. This will send the message to agency managers, employers and leaders at SUNY and CUNY that they should step forward and take action.

Next, Governor Cuomo and the Board of Regents should develop institutional capacity to assist community colleges in boosting success in every phase of their students’ college experience: from pre-collegiate preparation to graduation and first employment. New York benefits from having public institutions that are accountable to their local elected officials. But those institutions need to be accountable as well to the expressed priorities of state leaders.

Finally, New York needs to build new capacity for raising community college completion rates. It can accomplish this in several ways:

-

A competitive grant program for community colleges to try evidence-based innovations around student success, learning from established programs like Achieving the Dream and Pathways to Completion;

-

A web-based student success dashboard similar to that recently launched by the California Community Colleges system, which provides not only overall completion rates, but also completion rates for low-income, remedial, older and minority students;

-

A Student Success Center, similar to foundation-funded institutes in Michigan and Arkansas, that builds the evidence base on what completion strategies work, disseminates that evidence to policymakers and frontline providers, and convenes faculty and administrators for professional development around student success, open access and academic rigor.

-

Expansion of the Tuition Assistance Program to support low-income students who are now partially or fully excluded, including DREAMers, part-time students, foster youth and single adults.

Without a doubt, policymakers are starting to understand the important role that community colleges play across the state, and the economic toll of low-graduation rates has been specifically acknowledged by Governor Cuomo and other political leaders. In the 2013-14 budget, the Governor and Legislature agreed to create the Next Generation Job Linkage Program Incentive Fund, which will disburse $5 million to community colleges “based on measures of student success.” Earlier this year, Governor Cuomo also announced a plan to establish 10 new schools around the state modeled on Brooklyn’s Pathways in Technology Early College High School (P-TECH), an innovative partnership with IBM where students stay for six years and leave with an associate degree and hands-on experience in the working world.

Still, far too little has been done to tackle this enormous problem. Remarkably, while enrollment has climbed dramatically over the last decade, state funding has actually dropped. From the 2001-02 academic year to the 2011-12 academic year, state funding per student, in inflation-adjusted terms, dropped by 29 percent. Community colleges were forced to raise tuition by almost $1,500, a burden for which modest increases in need-based financial aid only partially compensated. The end result is a poorer community college system in which the largest funder is no longer the state, but the students themselves.

This is an enormous lost opportunity for New York. The future of the state’s economy rests on its skilled workforce, and that workforce is now being forged in the state’s 35 community colleges.