Our research uncovered additional data suggesting that low-income, native-born residents in New York are not pursuing entrepreneurship in large numbers. For instance, we examined the number of establishments per capita for the 50 ZIP codes in the city with the lowest median incomes—all of which have median individual incomes under $25,000.6 The ZIP codes with a larger share of native-born residents than the city average have 1.2 establishments per capita, whereas the ZIP codes with a smaller percentage of native born residents than the city average have 1.9 establishments per capita. For example, there are just 0.7 establishments per capita in Bed Stuy’s 11221 ZIP code, where the median income is $20,667 and 73.4 percent of the population is native-born. However, in Bensonhurst’s 11204 ZIP code, which has a similar income level ($21,281) but a smaller share of native-born residents (54 percent), there are 2.4 establishments per capita.7

Additionally, public housing developments across the five boroughs—where nine out of ten residents are black or Latino, and the median household income is $20,700—appear to have the lowest rates of business formation in the city. In 2012, there were approximately 218,000 working-age residents living in New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) buildings, but only 286, or 0.13 percent, reported owning their own business.

“Entrepreneurship among low-income, native-born minorities is quite low,” observes Andre Taylor, founder of the Taylor Insight Group, a New York-based consultancy that encourages entrepreneurship among minorities. “While there have been statistics suggesting occasional surges in entrepreneurial activity among African-Americans, my experience among the minority population in general is a resistance to launching a business.”

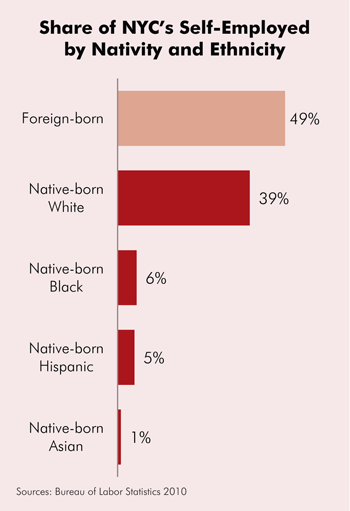

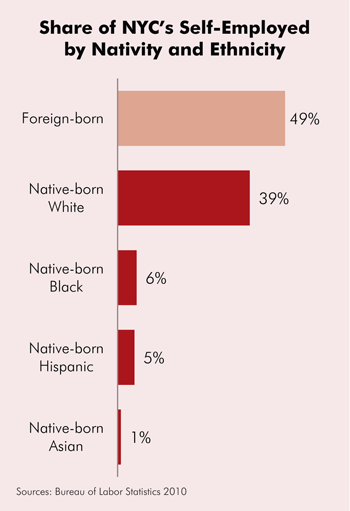

Citywide, native-born Whites make up 39 percent of all self-employed workers (59 percent of whom have at least some college education), compared to just 5.6 percent for African Americans, 5 percent for native-born Hispanics and 1 percent for native-born Asians. In the Bronx, Brooklyn and Queens, foreign-born residents make up the majority of the self-employed, but among the native-born in those boroughs, whites predominate: In Brooklyn, 36 percent of the self-employed are native-born White, compared to 7 percent African American and 5 percent native-born Hispanic. In Queens, where foreign-born residents make up the vast majority of business owners, 22 percent are native-born White, compared to just 5 percent African American and 3 percent Hispanic.

The different rates of entrepreneurial activity by nativity and race are not unique to New York. A 2013 report by the Kauffman Foundation found that 490 out of every 100,000 immigrants in the U.S. start a business each month (an entrepreneurial activity rate of 0.49 percent), nearly double the rate of native-born Americans (which have an entrepreneurial activity rate of 0.26 percent).9 Additionally, the African American rate of business creation is just 0.21 percent, lower than the rates for whites (0.29), Asians (0.31 percent) and Latinos (0.40 percent).10

But while the rate of business formation among low-income minorities is low, many of those we interviewed believe there now exists a tremendous opportunity to change this. “There is a huge potential to increase the number of low-income non-immigrant entrepreneurs,” says Donna Kelley, an associate professor of entrepreneurship at Babson College.

“There is an opportunity to do something in the Harlems and the Bed-Stuys and those other communities where you have folks who can be turned on and given the skills and tools to be entrepreneurs,” adds Sheena Wright, president and CEO of United Way of New York City and former head of the Abyssinian Development Corporation. “There are real opportunities and resources that can be used to really move the needle on entrepreneurship for low-income people.”

With fundamental changes to the economy punishing those without post-secondary credentials, Kelley, Wright and others believe more low-income individuals could begin to view entrepreneurship as an attractive option. After all, the manufacturing businesses that once offered decent-paying jobs and an opportunity for mobility for people with limited skills have largely moved overseas, and a significant share of the new jobs created in recent years offer extremely low wages, no benefits and little opportunity for upward mobility. In this economic environment, those who previously shunned the idea of starting a business in favor of the safer route of getting a job might view entrepreneurship in a whole new light.

There is also growing evidence that public and private sector initiatives in New York and elsewhere to promote and support entrepreneurship among low-income people can have an impact—from the annual Lemonade Day that gives young people the confidence that they can be a successful entrepreneur to programs that promote and teach entrepreneurship to kids in public schools or community colleges.

Perhaps most importantly, many residents of disadvantaged communities are already demonstrating significant entrepreneurial potential. Much of this is under the radar of policymakers and the media, but hundreds if not thousands of low-income residents in New York are earning income from informal “side-hustles,” from cutting hair in their apartment to day care. “There is a tremendous opportunity here, because there’s just such a huge amount of entrepreneurial talent, energy and desire,” says Magnus Greaves, a serial entrepreneur who co-founded 100 Urban Entrepreneurs, which supports young entrepreneurs from economically disadvantaged communities.

Increasing the number of low-income, native-born entrepreneurs in New York, however, may not be possible without first addressing the obstacles that prevent many from even considering entrepreneurship and make it difficult for those who do start businesses to get off the ground. For instance, people living in poverty often have limited exposure to entrepreneurial role models and mentors, a problem since entrepreneurs often get the confidence to start a business after seeing family, friends and members of their community succeed with their own ventures. Low-income individuals are also more likely to have limited financial literacy skills, not to mention paltry savings, poor credit histories and limited access to friends and family who can help finance a new business. And some are deterred from starting a business because earning even meager income from such a venture might cause them to lose government benefits, such as Medicaid, food stamps or housing subsidies.

Meanwhile, even as New York economic development officials have smartly ramped up support for entrepreneurs in recent years, there has been little focus on encouraging more low-income people to consider entrepreneurship. Although a number of centers offer workshops and one-on-one technical assistance for small business owners and would-be entrepreneurs, several low-income communities across the five boroughs lack these resources. “We have a lot of entrepreneurial assistance in New York City, but we have to do a better job at connecting them to urban entrepreneurs and being sure we have right mechanism of engagement in place,” says Bishop Mitchell Taylor, founder and CEO of the East River Development Alliance, a community organization headquartered in Queensbridge Houses, the largest public housing community in the nation.

Meanwhile, the workforce development centers that help jobless New Yorkers find work generally steer clear of recommending entrepreneurship, and the already small number of programs that teach entrepreneurship in the city’s public schools have been cut back in recent years.

New York certainly isn’t the only city that could be doing more. Marc Morial, the president and CEO of the National Urban League and an entrepreneur himself, says that policymakers around the country have largely failed to make expanding low-income entrepreneurship an economic and educational priority. “We haven’t created the kind of ecosystem which begins in high school or junior high through community college to nurture and support this idea.”

New York could be a leader in this area. As we detail in this report, there are many achievable steps that city economic development leaders, community-based organizations, workforce development providers and education officials could take to expand the pool of low-income entrepreneurs. Doing so could make a world of difference for low-income New Yorkers, spark economic growth in many distressed neighborhoods and bolster the city’s overall economy.

Click here to read the full report (PDF).