The Trump administration’s first budget, released on Thursday morning, made good on the threat to abolish the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). This drastic move will slash funding to artists and cultural organizations in all 50 states, but no place has more at stake than the president’s hometown. By many measures, New York City is the cultural capital of the United States, and that goes doubly, or really quintuply, when it comes to NEA grants.

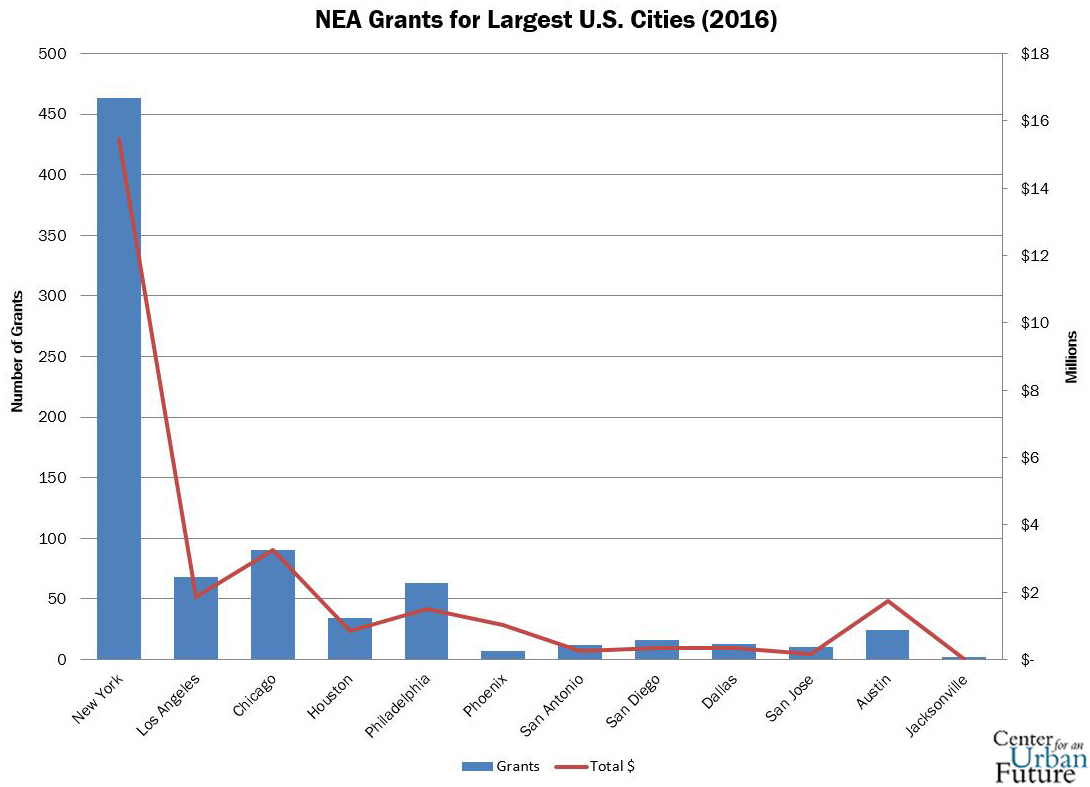

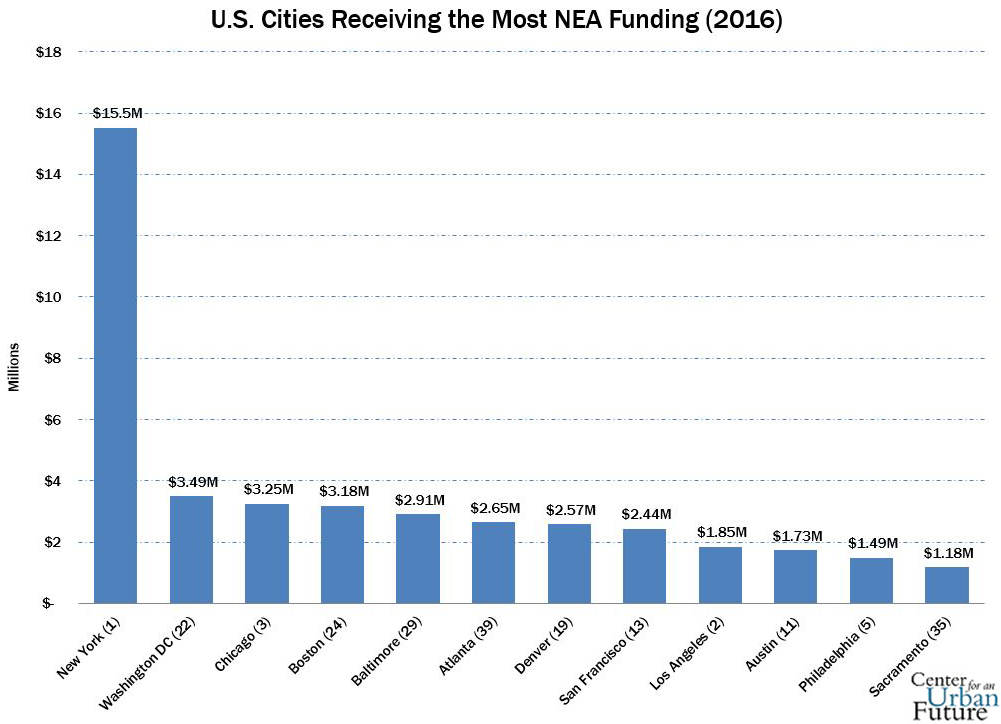

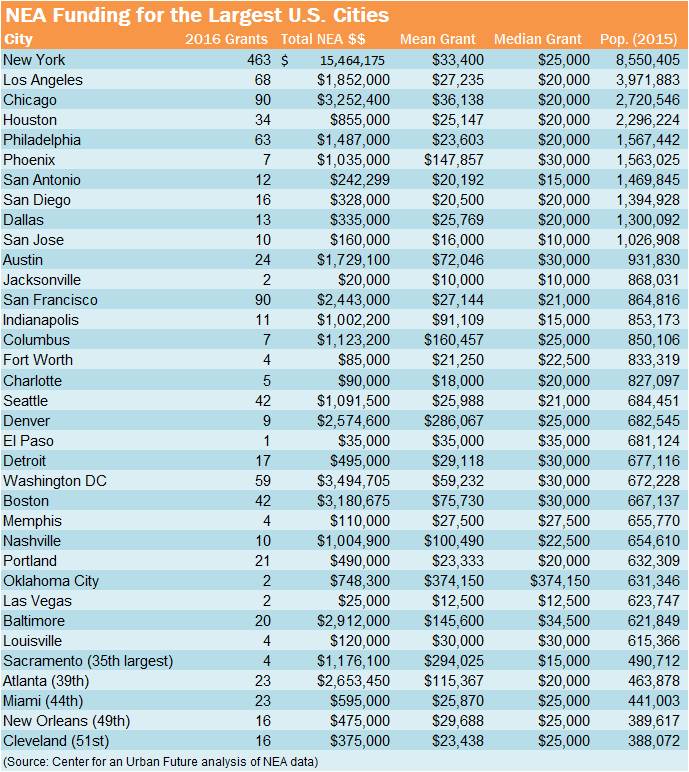

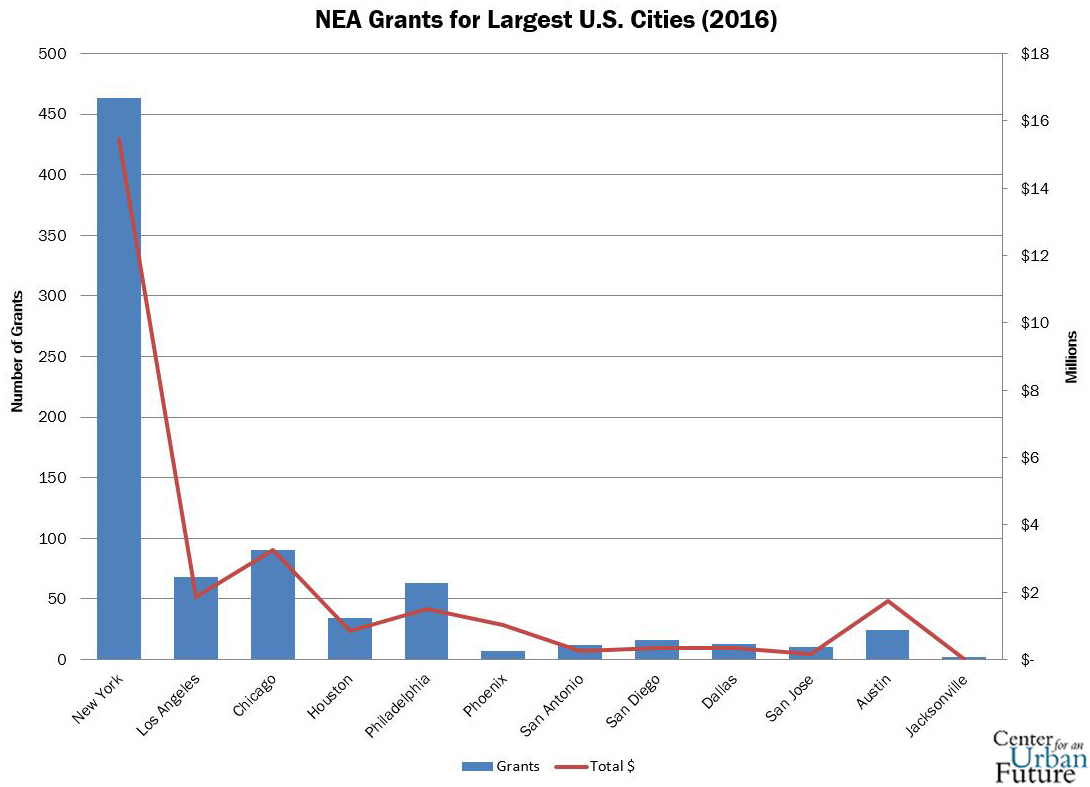

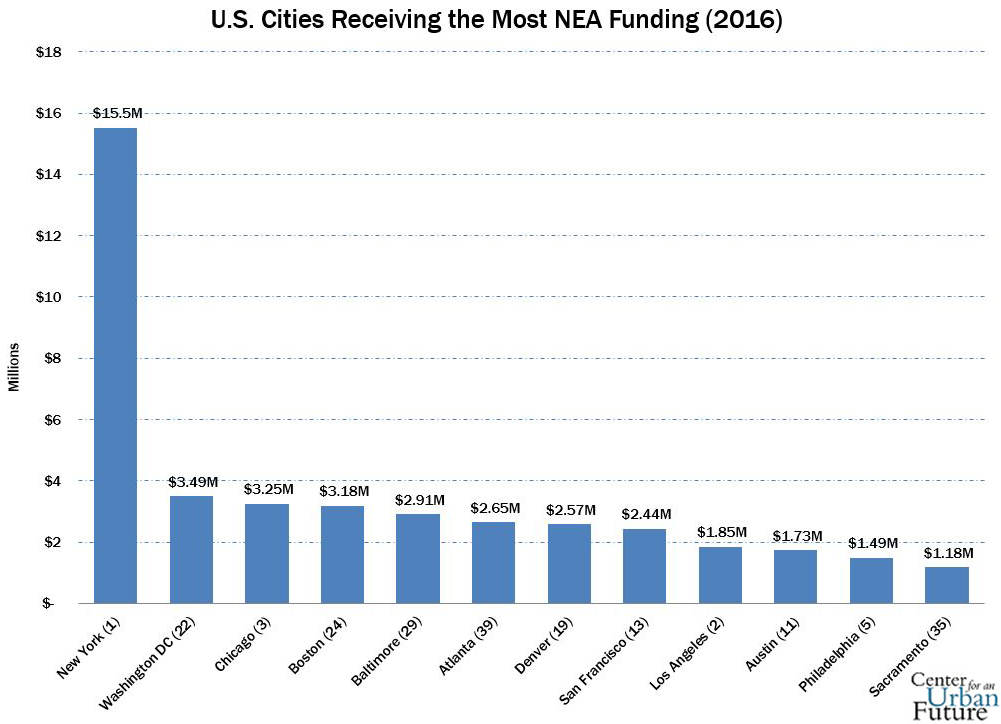

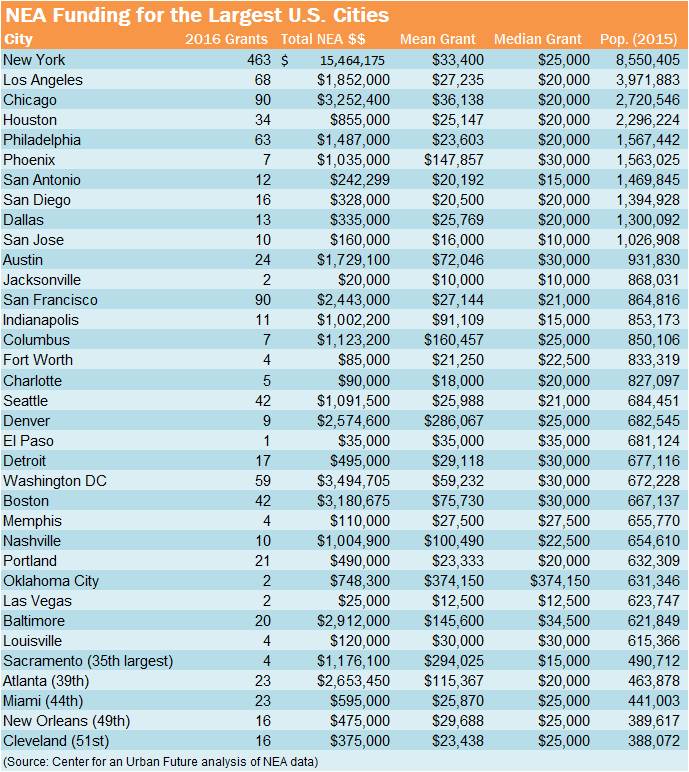

Both in terms of the number of grantees (463) and the amount of money allocated ($15.5 million), New York City received five times as much as the next closest cities in 2016. In fact, the city had more grantees than the next 16 largest U.S. cities combined. Any cuts to the endowment’s $147 million budget will be devastating to culture nationwide, but in New York, those cuts will be especially deep.

As the Center has documented before, creative industries account for a significant portion of New York City’s economy, with nearly 300,000 jobs or 7 percent of the workforce. Creative fields—including design, advertising, film, and performing arts—are outpacing growth in the city’s more traditional industries, such as finance, law, and education. Overall employment in the city’s creative industries rose 13 percent since 2003. Without the unparalleled concentration of nonprofit arts organizations and working artists in New York, there would be little foundation for the broader creative sector.

As automation displaces workers from more and more traditional industries and jobs, work will continue to demand more creativity, social skills, and the ability to cope with unpredictable situations. That is why everyone, including the federal government, ought to be investing in the arts, rather than trying to defund it for political ends. Culture is a bigger, and harder, job than it looks.

Although New York dominates the field, with its 463 grants going to 419 organizations (some received multiple grants throughout the year), cuts to the NEA will be felt across the country—and not simply on the coasts. The endowment handed out 2,445 grants last year, everything from the Sitka Summer Music Festival in Sitka, Alaska, to the Buffalo Bill Memorial Association in Cody, Wyoming.

Like New York, Chicago, and San Francisco have much to lose, with 90 grants each, while Los Angeles, Philadelphia, and Washington, DC, earned 68, 66, and 59 grants, respectively. There are significant geographic disparities: Houston, the nation’s fourth largest city, had 34 grantees, while Phoenix and San Antonio, the sixth and seventh largest, had only seven and 12 grantees last year.

More grants does not always mean more money: Baltimore had only 20 grants but received almost $3 million in funding last year, while Atlanta, the 39th largest city in the country, pulled down $2.7 million for 23 grants. Denver netted $2.6 million with nine grants.

Despite the large sums flowing to New York City overall, the city’s typical NEA grant is comparable to those of other cities. During the NEA’s 2016 funding cycle, the endowment’s median grant was for $20,000. In New York City, the median grant was $25,000—a figure matched by Cleveland, Denver, and Miami—while artists and organizations in Phoenix, Detroit, and Louisville saw a typical grant of $30,000.

As for New York City’s overall NEA haul of $15.5 million, it is still just a drop in the arts bucket. The Metropolitan Opera, for example, has an annual budget of about $300 million, while MoMA spends around $200 million a year. Even so, those $15,000 and $25,000 grants matter greatly to the emerging artists who receive them, like Jessica Lang Dance in Long Island City, Queens; the Bronx’s Ghetto Film School; and the Asian American Arts Alliance.

And yet New York’s impressive creativity boom has transpired not because of Washington’s generosity, but in spite of its frugality. With the exception of a slight bump in 2009, when the Democrats controlled both Congress and the White House—and awarded 3,047 grants worth nearly $160 million—the past decade has seen further Congressional cuts. This creative destruction continues a trend begun in the 1980s, one that erodes what is already among the lowest rates of public support for arts and culture of any developed nation. On a per capita basis, the NEA spends 47 cents per American, compared to $5.19 for Canada’s Council for the Arts, $8.16 for the Australian Council, and $13.54 for the Arts Council of England.

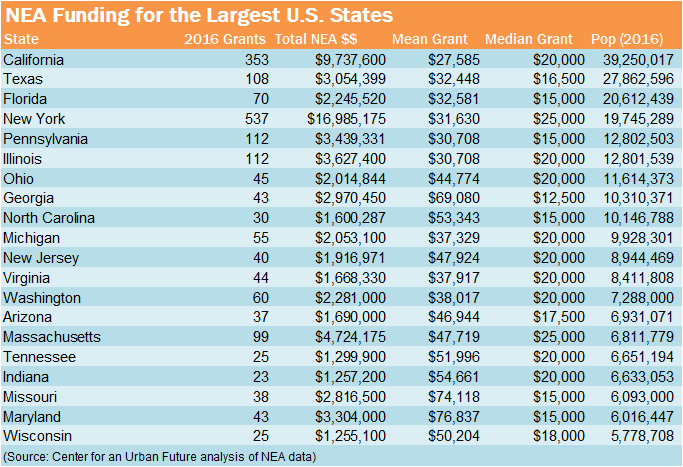

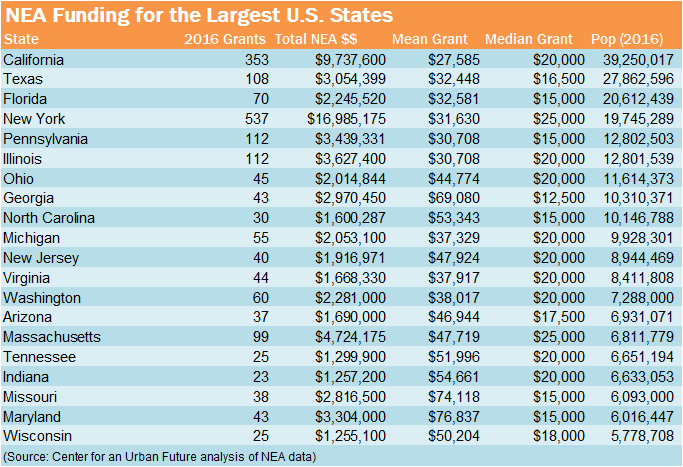

It doesn’t have to be this way. Tempting as it may be for U.S. Senators in, say, Texas or Arizona to argue that all the NEA money is flowing to the coasts, these states still pull in their fair share. While Phoenix may not draw much endowment money, Arizona has more grantees than North Carolina, close to as many as New Jersey and Missouri, and received more total funding than Virginia last year. And Texas, with 108 grantees, is ahead of Massachusetts and just behind Pennsylvania and Illinois. Symphony orchestras in Lubbock, Plano, Sugar Land, Temple, and Tyler, Texas, all rely on the NEA, with each garnering $10,000 last year.

Yes, Lubbock, Texas—at 260,000 residents, it will soon to surpass Buffalo in population—has its own symphony orchestra. The company is in its 70th season, and while musicians are not full-time, the conductor is, as is the administrative staff of five. These are just a few of the arts jobs that the NEA helps support, along with the thousands of other artists in Texas, and millions across the country, who receive the endowment’s backing. These are not just artists, but neighbors, community leaders, workers, and taxpayers.

Cuts to the NEA would hit New York City the hardest, but the effects would harm communities nationwide. With jobs in arts and culture poised to continue growing, there is a case to be made to boost NEA funding, not eliminate it. Despite comprising just 0.003 percent of the federal budget, the endowment’s return on investment is impressive. If the country is serious about growing the economy and creating jobs, funding the arts should be part of the plan.

(Note: All NEA funding amounts are for grants awarded during the 2016 fiscal year and disbursed as of March 1, 2017.)

Photo credit: Fre Sonneveld