Click here to download the full PDF transcript.

Presented by the Center for an Urban Future, the Center for New York City Affairs at Milano: The New School for Management and Urban Policy and the Regional Plan Association

Thursday, October 27, 2005, 5:45 pm to 8 pm

Panel One: Politics, Campaigns and the Issues That Matter

Evelyn Hernández, Editorial Page Editor, El Diario/LA PRENSA

Lee Miringoff, Director, Marist College Institute for Public Opinion

Hank Sheinkopf, President, Sheinkopf Communications

Moderator: Andrew White, Director, Center for New York City Affairs

Panel Two: From Rhetoric to Reality: Public Policy after Election Day

Lilliam Barrios-Paoli, Chief Executive Officer, Safe Space

Clara Hemphill, InsideSchools.org Director, Advocates for Children

Ronnie Lowenstein, Director, New York City Independent Budget Office

Robert Yaro, President, Regional Plan Association

Moderator: Jonathan Bowles, Director, Center for an Urban Future

Speaker biographies:

Lilliam Barrios-Paoli is president and CEO of Safe Space NYC, Inc., a nonprofit organization serving more than 25,000 children and families at nearly 40 different program sites throughout Queens and Manhattan. Prior to this, she was senior vice president and chief executive for community investment at the United Way of New York City, where she was instrumental in the creation and implementation of the September 11th Fund, which distributed more than $60 million in its first six weeks of operation. Barrios-Paoli has also taught at CUNY, Bank Street College of Education, Rutgers University and Montclair State College.

Jonathan Bowles became director of the Center for an Urban Future in September 2005 after serving as the organization’s research director for nearly seven years. The Center conducts research on economic development, workforce development and other New York City issues. Bowles is the author of more than two dozen reports and articles, which have been covered by publications ranging from The New York Times and USA Today to The Economist, and has published articles and opinion pieces in the Daily News, New York Newsday, The Village Voice, City Limits and Gotham Gazette.

Clara Hemphill is project director of the InsideSchools.org, an independent online guide to New York City public schools run by Advocates for Children, a nonprofit organization providing educational support, legal and advocacy services to parents, young people and professionals to help secure quality and equitable public education services. She is author of New York City's Best Public Elementary Schools: a Parents' Guide; Public Middle Schools: New York City's Best; and New York City's Best Public High Schools. Hemphill was previously an editorial writer and reporter for New York Newsday, where she shared the 1991 Pulitzer Prize for local reporting.

Evelyn Hernández is the opinion page editor at El Diario/LA PRENSA, the nation’s oldest Spanish-language newspaper, and a member of the paper’s Editorial Board. She was previously a reporter at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram and The Miami Herald and an editor and reporter at New York Newsday. Hernández is also a past president and founding member of the National Association of Hispanic Journalists and past president and founder of the Florida Association of Hispanic Journalists. She appears regularly as a political commentator on Kirtzman and Company on WCBS-TV and on New York 1.

Ronnie Lowenstein is director of the New York City Independent Budget Office (IBO), a publicly funded agency dedicated to enhancing understanding of New York City's budget by providing non-partisan budgetary, economic and policy analysis for city residents and their elected officials. She joined the agency in 1996 and was appointed director in August 2000, after having served as deputy director and chief economist. Prior to her work at the IBO, Lowenstein was an economist in the Domestic Research Division of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and taught economics at Barnard College.

Lee Miringoff is director of the Marist College Institute for Public Opinion, a survey research center that regularly measures public opinion in New York City and State as well as across the nation. The Institute is used as a source by print and broadcast media organizations throughout the country, and the Marist Poll has been called "one of the most widely respected surveys...and a key player in shaping news coverage for a decade" by New York Newsday. A frequent commentator on politics and polling, Miringoff is president of the National Council of Public Polls and also serves as a polling consultant for WNBC-TV.

Hank Sheinkopf has been a political, public affairs and governmental relations consultant for nearly 30 years. In addition to over 600 domestic campaigns in 46 states, he has worked on political and issue campaigns on four continents and in nine foreign nations. Sheinkopf was a key member of President Clinton’s re-election media team, and also consulted for the Social Democrats in the successful 1997 election of Gerhard Schroeder as Chancellor of Germany. In New York, Sheinkopf has been involved in electing nearly half the city’s congressional delegation and served as strategic advisor and media consultant to scores of campaigns at every level, including the victories of Attorney General Eliot Spitzer, Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum and Comptroller William C. Thompson.

Andrew White is director of the Center for New York City Affairs at Milano: The New School for Management and Urban Policy, where his writing and research explore the impact of politics and government policy on urban communities. He teaches courses on the politics of policy and criminal justice. Previously, White was chief editor of City Limits magazine and executive director of City Limits Community Information Services, where he founded the Center for an Urban Future. He is also a co-founder of the Independent Press Association and its local ethnic and community press collaborative. His work has appeared in The New York Times, New York Newsday, the Daily News, The American Prospect and elsewhere.

Robert D. Yaro is president of Regional Plan Association (RPA), America’s oldest independent metropolitan research and advocacy group, where he served as executive director from 1990 to 2001. Yaro led the five-year effort to prepare RPA’s Third Regional Plan, A Region at Risk, which he co-authored in 1996. He co-chairs the Empire State Transportation Alliance and chairs the Civic Alliance to Rebuild Downtown New York, a broad-based coalition of civic groups formed to guide redevelopment in the aftermath of the September 11th attacks. Yaro also teaches city and regional planning at the University of Pennsylvania.

_____________________________________________________________________

FRED HOCHBERG: Good evening. My name is Fred Hochberg. I’m dean of Milano – I can’t say Milano Graduate School – they changed the name. I’m the dean of Milano, the New School of Management and Urban Policy. I’ve got to get with the program. I want to thank you for joining us tonight. This is part of ongoing work that we are doing at Milano, in terms of examining City Hall, examining mayors, the influence of mayors, how we make change in the city, the role of policy and politics and how they overlap.

And in fact, I just had an afternoon seminar, which we brought in Ruth Messinger, who ran for mayor in 1997 and is now running a nonprofit. And we had a very lively conversation about running for mayor, women in politics, women in nonprofits. And, so, this is just part of that series.

We also, last year, had a conference on Mayors and Innovation and we will be running another conference looking at city issues and cities in crisis, looking at cities like New Orleans and New York City, that have had great crises and how they have dealt with that. And that conference will be in April.

I want to take a moment just to….since we are here at Milano…just to talk about it for just a moment. Milano is a graduate school in management and urban policy, focusing on training people who will run nonprofits, and ultimately run city agencies and departments. And that’s what we train people for.

And tonight’s seminar, tonight’s panel is really part of the extracurricular education that goes on in our school, in terms of trying to look at both a theory and practice and how they meld together, where they fit together, where they don’t fit together. And it’s part of what I think we do uniquely well, in terms of preparing our graduates to go out and deal with some of the thorny issues that are facing cities and, uniquely tonight, talking about facing New York City.

One of the things we examine is how much of a difference there is between Democratic or Republican leadership at the local level. And I’m hoping that our panel will also address some of those issues this evening, in terms of looking at the policy debate.

But mostly tonight, we are here to sort of examine the role of policy and the role of real thinking about thorny issues that are difficult and sometimes appear intractable but with the right kind of input, with the right kind of political will, we can make progress and have made progress. And our poor panelists are standing in the wings and I am going to turn this over to Andrew. I want to thank you all for joining us and I hope you will continue to come back for others in the future.

So, with that, let me introduce you to Andrew White, who runs the Center for New York City Affairs. Andrew?

ANDREW WHITE: Good evening. And thank you all for coming. I’m Andrew White, I direct the Center for New York City Affairs, which is an institute within the Milano School that focuses primarily on advancing innovative policies and programming in the nonprofit and government sectors to overcome urban poverty and to strengthen neighborhoods and families.

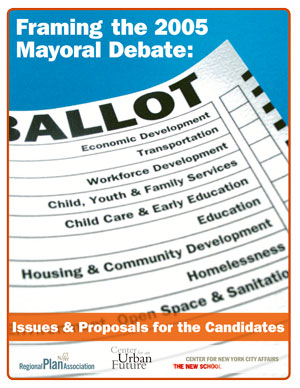

First off, I just wanted to thank a number of people who helped put together this report, which you picked up out there and which we put out during the summer. It’s called “Framing the 2005 Mayoral Debate” and the process of putting that together is really the inspiration for tonight’s forum.

At City Futures and the Center for an Urban Future, Neil Kleiman, who has moved to Seedco recently but ran the Center for nearly a decade, Jonathan Bowles, Tara Colton, Alyssa Katz and David Fischer, all helped out with it. At the Regional Plan Association, Chris Jones, Jeff Zupan, Robert Pirani, Jeff Ferzoco, Alex Yablin and Jeremy Soffin. And here at the Center for New York City Affairs Sharon Lerner and Mia Lipsit. Also, the New York University Institute for Education and Social Policy, Norm Fruchter wrote the section on education. And also I would like very much to thank Robert Sterling Clark Foundation and the Joyce Mertz Gilmore Foundation for making the report possible and the Milano Foundation for making this program possible. Enough of that.

I’ll get to talking about the report in a minute. But it seems to me that we’ve got an interesting switch in politics over the last few years. You could even call it a flip-flop. I hate to say it. It used to be that in New York City you could swing a reporter’s notebook anywhere near City Hall and you’d hit a political hack or a crony. This is sort of tradition in big city politics. But today you can still find that in some of the organizations that the City contracts with. You can still find that apparently in the Brooklyn courts. But if you want sensational cronyism, on an unprecedented scale, forget the old urban political machines. Now you go to Washington, and it’s become a national pastime. The federal government, in many ways, has become all that we used to denounce in local government and, oddly, now we’ve got local government that’s pretty clean, for the most part.

But cronyism is only one of the factors that people who do policy worry about when they try to get involved with government and make change. For people like us, who are truly devoted to advancing innovation, who are trying to transform or improve government, who are trying to make it more customer-friendly or more effective, the problem with government isn’t so much hackery as the reality of politics itself. It’s not first and foremost about policy. It’s about power and the ideas and reforms generally flow after the politics. That’s a point that so many of us miss unless we get a chance to work in a campaign or to spend enough time actually trying to accomplish something at City Hall or in Albany.

When the group of organizations represented here set out to produce this policy book on the mayoral campaign, we wanted it to be a resource for reporters, for campaign consultants, for bloggers, for public-spirited people who wanted to try and get the issues inserted into this campaign in a clear and public way. And we consciously thought to include at least some issues that we thought had political play. We couldn’t include all of those because we don’t have expertise, for example, on crime or anti-terrorism in these three organizations. Even so, we did hit on education and the future of the city’s economy, poverty issues, homelessness, transportation and such things. And we had some success.

The material in the booklet has been used by a number of people in the political world. It’s been in the blogs, it’s managed to shape some of the political coverage in the daily papers. And I think it has helped define some of the differences between the candidates in that coverage. It’s a very rich piece of reporting. I know it’s a bit dense, but I hope some of you will pick it up and read through it.

We pulled together the knowledge and experience of a large number of people who have worked in these fields for many years. And we reached out to people from many different points on the political spectrum, as well. This is not one agenda. This is not a group of organizations pushing their agenda. We tried to lay out the problems and solutions not from one organization but from several points of view.

I can’t begin to be comprehensive in any way in the summary of the material in here. But it’s very clear that the next mayoral administration and whoever is running that administration faces some very high hurdles. The fiscal disconnect may be foremost among them, if not this coming year, then in 2007. As soon as Wall Street’s revenues hit the skids again and as soon as the real estate market slows, the government coffers are going to look awfully empty.

The City’s transportation infrastructure is insufficient and aging and the indebtedness of the agencies responsible for that infrastructure is huge. Meanwhile, the bottom end of earners in the economy in New York City earn less each year, rather than more. And poverty rates have actually increased in the last few years, along with the cost of living.

And even as the City’s population exploded in the 1990s and early 2000s, the rate of new housing development lagged behind. There were just 50,000 more rental apartments in New York City in 2002 than there were in 1993, even though the City’s population had increased by about 700,000 people. Actually, almost 800,000. So, you wonder why we have a housing crisis? Not that we didn’t before. It’s only worse.

In any case, I won’t say that these issues have been completely absent from the political campaign. In this mayoral campaign, some very important issues have helped define the candidates, at least in a modest way. But issues have indeed been subsumed by politics. It’s inevitable. It’s rare that campaigns are about issues. They are much more often about personalities, about skillful political gamesmanship, about the art of shaping perception, about the size of the bank account and what you can spend on a campaign.

Tonight, we hope to explore all of this in a thoughtful way. Our first panel is going to focus on politics – the politics of policy. Lee Miringoff and Hank Sheinkopf – is Evelyn here yet? I hope she will show up soon, but the two of them ought to be able to have a great conversation, nonetheless.

Our first panel will focus on politics. How have Michael Bloomberg and Freddy Ferrer used issues to define themselves and to outline a vision for the future of the City? Have they tried to reach the public in a way that conveys big, substantive differences on important issues? How do politics, polls and the media shape or distort the issues that are so important to the neighborhoods and the people in New York City. And as we head into the debates coming soon, starting Sunday, running up to election day, is there any hope of charging up the substance of this race, above the creation of image that we are seeing in the advertising every day?

During the second hour, Jonathan Bowles from the Center for an Urban Future will moderate a slightly different discussion. We will switch gears and discuss some of the most pressing problems facing the City today. What issues have been flying under the political radar during this campaign? Can we expect to see anything different, anything new in the way that the City is run and the way certain issues are addressed, after November 8th?

So, to introduce the two panelists: Lee Miringoff is director of the Marist College Institute for Public Opinion, which is a survey research center that conducts polls in New York, as well as nation-wide. He is also president of the National Council of Public Polls and serves as a polling consultant for WNBC TV.

And Hank Sheinkopf has been a political and public affairs consultant in New York and around the world for almost 30 years. He has worked for Bill Clinton, for Gerhardt Shroeder, for Elliott Spitzer, Betsy Gottbaum, Bill Thompson and many, many others.

So, we are missing the media piece, unfortunately. I hope Evelyn will stroll through that door any minute.

Hank, you said to me the other day that traditional politics in New York City are all over and that everything has changed. What did you mean by that?

HANK SHEINKOPF: We used to think about New York City politics as being simply a function of ethnic and racial tribalism. And what has occurred, very interestingly in the last several years, and I think that part of this is a reaction to the divisiveness of the Giuliani years and a reaction to the election of the first black mayor, David Dinkins some time back. The politics have now become more based on class in this town, than race. And I think that’s rather important. So arguments about two cities don’t work, only in so much as they have a social class basis. If you look at the Weiner campaign, which was pretty interesting to me, this past Democratic primary, what you see is a campaign that proves for sure that the myth of ethnic, outer borough, white working class is simply a myth, that those people don’t exist. The population of this City has changed dramatically. The economics of it have changed dramatically. If you look at Southeast Queens, what you see is an area of the county that has a higher per capita income than the rest of the county. And Southeast Queens, for those of you who don’t know, is black. So there’s something very different going on. You don’t know what the impacts of the swelling Asian population will be, particularly in the outer boroughs. What we see is a Manhattan….when I first got to Manhattan as a young man – I was young once – what was fascinating was that you got here. Now, people get here not because they strive but because they can buy their way in.

So, the sense about what makes the city work poetically is very much tied to how it works overall. And it is a very different place. The population shifts, the voter view and it has a lot to do, I think, with why this election will or will not work out the way some people think it will.

If race is not the issue and social class is, then you have to have an argument that permits social class and economics, those places that Democrats tend to do best in. That propels people with some action. And you need some intensity behind the argument. When you are running against a billionaire and you lose momentum for a moment, you lose the campaign. And that moment was Diallo, and it’s been downhill ever since. But it tells you that race, no. Attitudinal stuff, yes. Social class, yes. Changing population, yes. One astounding statistic and then I will pass the mic: 20 years ago, in the county of Queens, 50% of the population were Jews. Today they are 15%. A count of households, prime voter households, which is how we determine who votes and who doesn’t vote: New York City overall – take the Jews again because it’s kind of interesting – top population 1950, 2 million. Today 850,000, of which 20% are Russians, which means you have 680,000 with prime voter households of under 350,000. It’s astounding.

Look at the rest of the population. What you see is a very different city and the impacts won’t be felt in this election necessarily but certainly in 2009.

ANDREW WHITE: So, given those demographic shifts, attitudinal shifts, Lee, what do you see as the issues then, broadly defined, that play to that change?

LEE MIRINGOFF: I was just going to comment and maybe then go that way. First of all, it’s nice to get away from number crunching, which is what we’ve been doing for about six months now, and to actually be back with students in an academic setting, graduate students studying these kinds of issues.

I was just going to comment on what Hank was saying. If Rudy Guiliani’s administration fueled some racial division, I think part of what we are seeing also is not only the demographic shifts, but reflected in the strategies and style of what the chief executive is all about now. And if Giuliani was fueling the racial divisions, certainly the Bloomberg administration’s strategy was to try to mollify those differences. And we saw in the survey we did a month or so ago about the traditional question: are you better off now than you were four years ago? And we asked it in a whole slew of issue areas from the economy to healthcare to crime. And what we were struck by in those numbers is that the differences along racial lines were very muted in the city response. It is a very, very different picture. And I would argue that – we started talking about how politics, to some degree, overshadows policy and it certainly does. And I’m sure going to get into that this evening. I would also suggest that the strategic efforts of these various administrations and their leaders fuel divisions, don’t fuel divisions and we’re seeing now a little bit of that kind of fueling attempt.

Bloomberg was basically out to get a certain group of voters that he didn’t get four years ago and I think he’s made a concerted effort in these four years to attract them. And I think we are seeing those results right now.

ANDREW WHITE: Who, exactly, are you referring to?

LEE MIRINGOFF: African Americans. Clearly, just the way it’s worked out, a much larger swing group right now. In 2001, I believe, in the exit polls Bloomberg got 25% of the African American vote. The number right now looks like it’s going to be close to 50. It probably won’t be in the end. But it will probably come close to doubling his support among that community, which deals with other things around partisan attachments breaking down and all that, which we can talk about.

ANDREW WHITE: Yeah. I want to get back to the polling. What do you think about the issues that resonate with that kind of an audience, with that kind of an electorate? With folks who are feeling better off than they were four years ago?

LEE MIRINGOFF: There is no doubt and I’m sure Hank has seen this also, that there has been an issue shift and we’ve seen it reflected in the campaigns. It’s reflected in your booklet. Eight years ago crime was the major issue. We’ve got one through the security concerns of four years ago. And now issues that more often have reoccurred on the scene: education, healthcare and especially this time, housing, that you mentioned in your introductory remarks. In many ways, the housing crisis in the city has gotten involved in both campaigns.

Part of what the Bloomberg campaign has also been about is, again – not to overuse the word “strategically,” but they have been plugging up every possible weakness with lots of money. And in some of our initial surveys, which I am sure will be reflected in their private campaign polls, talked about things that voters were unhappy with Bloomberg about and it was initially housing, and it was healthcare and it was the issue that people felt he didn’t care about. Concerns like that.

So, fast forward, during September and October, what are the ads we’ve been seeing? We’ve been seeing the ads about housing, we see the ads about issues about healthcare costs rising. We saw the prominently used African American female who was talking in the ads about, “You don’t have to be warm and cuddly to show that you care.” You’ve probably seen that ad.

In a sense, the politics of what that campaign is about, fueled by lots and lots of money, have been efforts to plug up specific issue weaknesses that they have in the campaign. So there is this shift and if you ask what the number one issue is, it’s education and again, that’s permeated the discussion as well.

ANDREW WHITE: Evelyn Hernandez, good to see you. Evelyn is opinion page editor at El Diario/La Prensa and she’s a member of the paper’s editorial board. She is also a founder of the National Association of Hispanic Journalists and you may have seen her frequently on Kirtzman and Company and on New York 1. Evelyn, do you see substantial differences between these two candidates on the issues, beyond the personalities?

EVELYN HERNANDEZ: Do I see substantial differences? I do. I do see significant differences because I think that Fernando Ferrer is trying to – and we can argue about how successfully he has been able to accomplish this – but I think what he has tried to do is talk about a larger issue and people say that he is revisiting the two cities theme. But I think he has tried to talk about two cities in some form or other, at several points in the campaign, and sort of resurrected it directly this week. But, in fact, this was his theme four years ago and despite the mainstream media, mostly, sort of painting it as a divisive theme, it’s actually a theme that rings true for people who are living it. Very much so.

And I think if I were to…in critiquing his campaign, I just think he should have come out with it stronger and more forcefully from the very beginning again this year. Because, in fact, when you are talking about education, when you are talking about housing, when you are talking about jobs, and the city has lost jobs, despite all the figures that say that unemployment is down. All of us know that when people stop looking for work they stop getting counted as unemployed. Those issues are issues of the haves and the have nots. And those are issues that are not about race at all. They are about economics. And they are about who has been able to participate in the economic boom of the last four years. And who has been left out?

And when you talk to people around the city, a lot of people feel like they have been left out. They feel like they are paying higher taxes. It’s great that the property values have gone up but what are you going to buy? When you sell your home, what are you going to buy? You can’t afford to buy anything else so basically your house is worth a lot, if you are planning to sell and move to Wisconsin. But if you want to live in New York City, realistically you’re not able to benefit from those kinds of increases. If you have two or three homes, you can benefit but not if you are living in the one house that you own.

So, there’s a lot of disenchantment around the city with this idea that somebody has made money in the last four years and somebody’s done well in the last four years but “it ain’t me.” And in terms of education, it’s also a matter of for a vast majority of people in this city, public education is all you got. Even Catholic schools, if you have been following the news, are now beyond the reach of a lot of people because of economics. They’ve gotten so expensive. And Catholic schools are closing down because there aren’t enough people to go to those schools anymore. So Catholic schools, which used to be the working class and certainly in Puerto Rican neighborhoods and Latino neighborhoods, maybe you couldn’t send your kid to a private school, to a Dalton. But you scrimped and saved and sent your kid to parochial school and, in fact, if you talk to a lot of the middle class and upper middle class Puerto Ricans in the city now, who are in their 40s and 50s, you will see that a lot of us went to Catholic school at some point in our education.

So, it’s really – the two cities theme is really a question – is economic, when you look at it as an economic theme and not a racial theme, it’s a very true. It’s a reality of what New York is and what New York is continuing to become in 2005. And so I think, in that sense, a lot of people do believe that theme.

Now, of course we aspire to – we tend to vote toward our aspirations and not for our reality, so everybody would prefer to be a rich billionaire than to be a middle class homeowner, clinging by your fingernails to the middle class. So, in that sense, perhaps people would rather vote for a Bloomberg than a Ferrer. But I think that when you actually talk to people on the street, when you actually go out and talk to people about what their concerns are, their concerns are that they are not going to be able to stay in the middle class. That the struggle now is to just survive and not lose ground and fall backwards.

Now, within that, where race comes in is that unfortunately, the reality is also in this country that when you talk about poor people specifically, and when you talk about people who are struggling, a lot of those people do tend to be the people of color. So in that sense, race plays a role. But it’s really an economic issue. And when you look at it that way, I think that’s really where Ferrer has a message that rings true for a lot of people. Unfortunately, the question is how many people have been able to hear it consistently given the fact that he has been so outspent by his opponent.

ANDREW WHITE: Right. And there are two points to bring out of that and comment on, first of all: how has the two cities message resonated broadly with the electorate. Hank?

HANK SHEINKOPF: What I said before about the two cities, not as race, but two cities as social class, is really where the city is heading and I think the problem for the Ferrer campaign has been inconsistency in message. There is nothing wrong with the argument. The argument has standing. The argument is, in fact, accurate. And it’s no different, by the way, no different than arguments, similarly made by others in public life going back to the beginning of my career, which is a long, long time ago. So this ain’t new. It was called divisive in 2001 because Al Sharpton was hanging around. Had he not been there, it wouldn’t have been divisive, it would have been, “Oh yeah, he’s on my side, I’m a blue collar guy from the outer boroughs.” But that’s the difference. So the reporting corps saw that as a way to kind of destroy the argument.

Is it, in fact, a good argument? It’s a very good argument. But my business isn’t policy. My business is politics. And the bottom line is a simple one. If you don’t reinforce the message, you look like John Kerry. And that’s part of what’s happened here. Money is certainly important to politics. No question about it. But if your message is good, you can break through. There’s a slew of them. I can go on and on and on, people who spent hundreds of millions of dollars to get elected and didn’t draw flies.

If the message is good, if you galvanize the base, get the people out, you win the election. The other problem is Democrats are just absolutely full of junk. I was at the Stonewall Democrats last night and what I sensed was energy in the room. When I talk to Democrats in this town, and in Washington, I get sick. You want to win a class battle, which is what this Democratic primary ought to be about? You go and fight social class. You don’t talk about it. But people have vested interests in ensuring that nothing changes. And Ferrer has done a bad job, until recently, of reinforcing what is a reasonable argument, because it has legs, particularly in an emergent population. Particularly in a city going through demographic changes and particularly in a city where striving is the motto. Where striving is going to become a lot more difficult for a lot more people.

ANDREW WHITE: Would you address or reconcile what everyone was saying about the haves and have nots and the Weiner campaign talking about the middle class, which wasn’t the same thing?

HANK SHEINKOPF: Oh, no question about it. When Fernando Ferrer stands up and talks about two cities, the press corps picks it up differently than when Anthony Weiner talks about outer borough, middle income people. There is no question about it. And I’m someone who was at the first shoot out, with Herman, in ’69. The second shoot out in ’73, where he helped them rob the election from him. And I remember standing in 1969, closing up polling places in the Ravenswood Projects and I am a blue collar kid from the outer boroughs, by the way. Without free university and the things the city used to have, I would be cleaning the toilets here. There’s no question in my mind, because that’s the world I came from.

I was a unionized restaurant worker and I’m an ex-cop. So my perspective is a lot different. That’s the world I come from. And I understand what he’s talking about. In ’69, when we closed up polling places, Badillo’s name was not on the ballot. The machines were rigged. People had ripped off the labels. This is real stuff. This is the stuff that happened. And that’s the way it was. So when a Puerto Rican guy stands up and says, “Two cities.” The press corps – remember, New York City politics is covered on a daily basis by seven daily newspapers, including El Diario. Seven daily newspapers. So the free press here determines more of what occurs and how paid media is received than any place else in the country.

If you are running a mayor race in Houston, and I’ve been at that movie, you shut off the newspaper the day the television goes up. Paid media goes up, goodbye newspaper. Throw it out the window. Not so in New York City. Free media reinforces everything that goes on. It sets the structure for what paid media does. The difference here is when Anthony Weiner stands up and talked about middle income people in the outer boroughs getting banged around, people tended to pay attention. The problem is there ain’t enough white, blue-collar people in the outer boroughs to vote for him. That’s the difference. They don’t exist.

Anybody who doesn’t believe me, go take the number 7 line. Go take the number 7 line. Where are the great Irish that used to live on Briggs Avenue? They’ve been gone for 35 years, in the Bronx. The Jews of Mosholu Parkway. This is not the city people are talking about. So what happens to the white, outer borough working class – what is left of them – is they have this romantic vision of how the city used to be and it doesn’t exist anymore so Weiner kind of got lost. He kind of got lost.

And Ferrer didn’t get the numbers, not because he made a bad campaign in the primary but because of the very simple fact – and this has to do with the New York City political culture – people tend to view overall, the mayor as an eight year term. Think about it. They just don’t turn out mayors. And incumbents, by the way, nationally get re-elected at the rate of about 98%. I want to make two points, in my lifetime there have been two mayors who have served one term and that’s pretty interesting. And I’m old enough for Wagner, which is really the problem for me. And the ass end of O’Dwyer. But be that as it may….

Dinkins and Beame. And you have to then ask yourself, why do we, with a five to one Democratic registration edge, return Republicans or anybody else? Why do we elect Republicans? If you look at the history of New York City politics, going back 60 years or better, what you find is a pattern of electing Republicans or so-called fusion candidates, based upon the crisis of the moment i.e. LaGuardia – corruption, Republican; Lindsay – massive ethno-demographic change overnight (by the way) that reshaped Brooklyn and the Bronx. It was almost like that. White flight and the destruction of the political machines, which Ed Koch helped to make happen by getting rid of Carmine DeSapio. Rudy Guiliani – crime. Whether it’s true or not is not an issue. Mike Bloomberg – 9/11.

The problem that the Bloomberg campaign has been able to overcome is that they have, in fact, extended the crisis out, in a city where for the first time in New York City history….and I’m the guy that fed this to the Times, the turnout should normally be majority minority. So, while the city goes through transition, when the mayor’s term is seen as an 8-year span and when people are just depressed, not voting is voting. This is something I learned and I used to teach graduate students about. It is the decision to actively not participate. It is the greatest form of power, the forcing of a non-decision. Therefore, not voting is a pretty powerful argument. So, when people don’t turn out, they are submitting to the whims of New York City politics.

ANDREW WHITE: But both these messages are pretty populist. Weiner and Ferrer clearly were playing populist messages to different audiences. You could argue even that Bloomberg is trying to make a populist message out of the way he’s selling who he is. Twisted populism but it’s populism.

HANK SHEINKOPF: It is populist. This is a populist place. Look, there are three stools to the populist chair. For those of you who are students, Kazin wrote a great book about populism. There are four legs to that stool. Overall alienation, an economic argument that works, a religious component and a general desire to burn down the building.

So, you have to look at… the Democratic Party whose leadership is…I don’t care who they are, I think they have failed miserably to get people interested at all, because incumbency is more important [to them] than taking dramatic overture. But be that as it may.

So, that all being said, New York City politics being no different in some ways than national politics. I can tell you nationally, having worked in 46 states and having been a presidential guy…

[tape cuts off briefly]

HANK SHEINKOPF: Religion is still a quantifier. So, Bloomberg has been able to buy that out and churches have always been a place of organizing. So look what’s happened.

ANDREW WHITE: So Lee, and Evelyn, to what degree is the content of Bloomberg’s administration been a selling point for him on the campaign trail? Why have all of these churches and community organizations and policy wonks and others rallied to his case?

LEE MIRINGOFF: I’m not sure this totally answers the question but if I rewind back to last spring, Ferrer was ahead of Bloomberg. Bloomberg’s approval rating was in the low 40s. Most people in New York thought he was heading in the wrong direction. It’s sort of a funny thing that’s going on the last six months. He has really – if we ask people – we haven’t done this, but if we ask people whether they think Bloomberg has been popular for a long time and it was always looking like he was going to get re-elected, people sort of think that’s the case. But it really wasn’t. And Hank alluded to it earlier. And I think rather than having a cross-cutting issue like the two cities, which might have galvanized the base, which hasn’t happened, we’ve had some defining moments that shifted with the Diallo comment and we see that in the numbers.

That was the time Ferrer fell below Bloomberg for the first time, in April. And the only other time that there was a slight evening in the numbers was right after the West Side stadium debacle for Bloomberg, where he was doing well and that sort of went down. People were upset with him for a variety of reasons, because he spent so much time on it, not because they wanted it. And then he recovered quickly from that. And then the last time, the major change in the numbers, has been with the alleged subway terrorist threat. And those have been the three issues, using the term that way, that really moved people during this campaign.

There hasn’t been, either happily or unfortunately, the kind of dialogue on issues. So the answer is, I guess that there’s been a lot of other things going on that have been capturing the public attention. And some of it was self-inflicted by Ferrer and others of it was just the way things broke.

ANDREW WHITE: Do you see those the same turning points in the Spanish-language media as you do in the English-language media?

EVELYN HERNANDEZ: Well, I think the Diallo gaffe was certainly a serious gaffe across the board. And I think that more than the actual words, it was the sense that Ferrer was trying to please, to pander, to please the group that he happened to be in front of. And that’s unfortunate, because his history is not one of pandering on this issue or on any issue having to do with police brutality or these kinds of police and the community and community issues. And in fact, the people who were criticizing him when he made that gaffe had done a lot less or nothing in Bloomberg’s case. And he wasn’t even in the picture at the time.

But, be that as it may, I think that he came back from that and I think that probably the high point for Ferrer has been the night that he won the primary and there was some question and some media made a bigger, played this differently, the fact that he didn’t have the 40%. But anybody who follows elections was pretty confident that he had a solid 40% of the vote and there would not be a runoff. So it was interesting to me to watch how the mainstream media played up the iffyness of it when I know that a lot of those reporters knew that that it was a pretty sure thing that he was going to have the 40%.

ANDREW WHITE: So, you think the media was intentionally shifting that?

EVELYN HERNANDEZ: Well, I think that if Anthony Weiner had been the one who had gotten 39.95% of the vote, that there wouldn’t have been so much hedging about whether it was 40% or not. I think that there would have been a lot more confidence in the media that the 40% was there.

LEE MIRINGOFF: What did Messinger get in ’97, in the primary?

ANDREW WHITE: A couple of percent less. It was close.

EVELYN HERNANDEZ: Right. I think it was that the speech that Ferrer gave that night was the best speech I’ve heard him give in a long time, maybe ever. I don’t know how many of you heard it but it was a very eloquent, sort of, two cities speech but where he said, “This is our time and this is your time. Your time is now.” And in fact, when we endorsed him on Tuesday, we quoted from the speech because it was such a great rallying cry. Unfortunately, we haven’t heard that speech again.

ANDREW WHITE: Well, certainly these candidates are both putting populist topics out on the table, with their weekly or more than weekly statements about different issues. But to what degree, then, is the media’s response to all that driven by the polls? To what degree are the polls driven by the media response? To what degree is that shaping what we are seeing?

EVELYN HERNANDEZ: If I could jump in here, I think that there are several things going on here. First of all, I agree that Ferrer’s message has not been consistent. I think that’s been a problem. And he needed to be consistent and hard and steady throughout because he was facing two very daunting aspects here, which is he was facing an incumbent and people tend not to vote out incumbents. And he is facing an incumbent with a whole lot of money.

And we forget that people were mad at Bloomberg because of the cigarette ban and educators, a lot of educators in this city are still furious with Bloomberg. There are other people in other agencies where Bloomberg has made changes at the top and then left them alone and those people are happy. But people in education, where they were micromanaging to the point where teachers were getting scolded or were getting warnings because their bulletin boards didn’t look right. In that area, which really was happening, there’s really a lot of unhappy people, people who are not happy with Bloomberg at all, because they feel education should not be run like a corporation.

But I think that it’s very interesting the way that a candidate of color, a Latino candidate in this case, how those sort of stumbled and the dips in the polls are reported, is a much more dramatic – the Diallo thing was a very dramatic gaffe and every time he stumbles or every time there’s even a dip in the polls, it’s just this sort of very dramatic – to the point where people don’t bother to point out that Bloomberg himself was 20 something points behind. Whenever he was 20 points behind, a few weeks ago when he first was 28 points behind. Bloomberg was 28 points behind or around that many points behind, four years ago and the guy won the election. Things like that, that don’t get pointed out. And that elections tend to be roller coasters. And so it seems like when a minority candidate is running or a Latino candidate is running, the advances that he makes are minimalized and whenever he does make a mistake, it’s really given much more dramatic play.

ANDREW WHITE: Although, as we were saying before, when you look across race and ethnicity, you see similar responses to the polls, even in terms of not so much support for Bloomberg but being positive about Bloomberg. It’s kind of remarkable to see. He’s got positive approval ratings in every borough in the city.

LEE MIRINGOFF: I think that the campaign, more than anything else, has set that agenda. And I think that if you compare, and I think Evelyn has mentioned this and I agree with her, part of the problem – the money notwithstanding, which is a big notwithstanding in this particular campaign – but part of the problem has been, I think, that they were trying to do from the Ferrer campaign several different things. And I think, at times, and I’m not inside the campaign but it looks like at times they played to the two cities theme and at other times they were trying to pick up more to the middle. And that’s why some of the – I don’t think the Diallo thing was necessarily a huge accident. I think it was something that was a big problem but if you’re picturing two cities, you shouldn’t be doing that as well, because now you’re in a sense putting a damper on your own support. And on the base you are trying to mobilize.

But I think the campaigns are the ones who set that agenda. And I think that the media is reflecting that more than driving it, in this case.

ANDREW WHITE: Even when one candidate can dominate the paid media?

LEE MIRINGOFF: The paid media. But not the free media.

HANK SHEINKOPF: I have to defend reporters. They’ve got to write stuff that fills that birdcage at the end of the day. Nobody remembers the bylines of the stories but something has got to get filed. And reporters thrive on conflict. That’s what makes stories. So a dip here, a dip there, especially when you are up in the beginning and you are way ahead of the incumbent and that’s the drama that moves it. Do I think that the gaffes that the Ferrer campaign has made, which are not insignificant, are viewed by the public –

Let me back it up, campaigns are often seen, in my experience, by the public, as precursors to how someone would govern. And errors are remembered. And if you run a bad campaign, people don’t think you necessarily are going to be able to do the job.

The other thing that comes to mind, and I think that all things occur within a liquid kind of an environment of the moment. It’s like polling data is fresh in the moment it’s taken. It’s reflective of that moment. Then we think about how long it’s generalizable, and how it has statistical reliability.

Same rule applies to the general message creation and development and movement of that message. We have two things operating here. One I call the delusion of fusion, that somehow if you create fusion arguments in New York City politics, it’s better government. And that it’s really cleaner government, when that’s just nonsense.

ANDREW WHITE: What do you mean?

HANK SHEINKOPF: Contracts. There’s a great book written by a political scientist who has since left the planet. And the title is indicative – he did a lot of books on Chicago and the Chicago machine. But the title stays with me: “Don’t Send Nobody Nobody’s Sent.” People don’t do business with government people they don’t know. They do business with people they do know. So it’s kind of nonsense that fusion is going to make you cleaner. That’s garbage. What has happened here and what the Bloomberg management style, which has leaked into the campaign and the Ferrer campaign has followed with a similar kind of campaigning to its own detriment, is what I call the “rationalization of the irrational nature of politics.”

There’s nothing rational about how people make decisions in the voting booth. I don’t want to blow anybody’s brains out, but these are not intellectual arguments. We make it too difficult. The average guy, average wife, woman, man, husband, whoever is the breadwinner, comes home – and forget you live in New York City, but even if you live in Staten Island, okay – that was a joke. I don’t want to offend anybody from Staten Island. They’ve got to figure out when the babysitter is going to get there so they can get in the car. And in some parts of this country, you can drive 20-25 miles to stand in line, after you picked up the babysitter and picked up your wife and your husband, you get in the car, you drive to the voting booth, you stand in a line. You stand with the registrar, you put your head down, the registrar gives you the book, you stand in line and the registrar has bad breath. You go into the booth that is badly lit. You pull a lever. You can’t figure out the ballot. They make your life miserable. You finally figure it out and you cast your vote, you close the machine, you step out and drive all the way back twice. Not rational. Okay? Doesn’t make it easy.

People also don’t respond to normative messages. Not rational. If X happens Y will occur. No. It’s about emotion.

So what Bloomberg has done, if you look at those spots, there’s nothing emotional about them at all. They are very rational, right ahead, straight ahead arguments. And the Ferrer campaign has produced non-emotional arguments. You do not defeat an incumbent. In 35 years of practice, I know one simple thing, no incumbent is defeated without a negative or comparative argument with velocity. No incumbent is defeated without an emotional argument that has a comparative or negative component. Where’s the beef, pal? Why aren’t they doing it? It’s because they have decided that they are going to fall into the – they are going to try to rationalize an irrational process. It doesn’t work. That’s why they are going to lose and they are going to lose by big numbers.

Could you even up the money scored? No, you can’t. Can you make a dent in it? Could spots be about people and the way they live and about schools in real terms? Not what you say but demonstrated, so you can prove case positive, you were the answer to the argument and the pain people feel? Yes, you can. But they are not doing it.

ANDREW WHITE: You didn’t see – throughout the primaries there was almost nothing but negative campaigning going on, toward Bloomberg. The four Democrats were all targeting Bloomberg with negative campaigns. And it didn’t seem to work. Look at Gifford Miller.

HANK SHEINKOPF: Right off the top of my head, okay: this is the house that Mike Bloomberg lives in. It’s worth about $35 million. It’s on 79th Street, across from the Park. Now, let’s look at where you live. You live on 149th Street and the Concourse. Pretty nice, huh? You’re never getting out. Your job? You’re a coffee boy. You go downtown, you work until your feet bleed. Maybe you make some tips there. Then you come back. Your child: in a school that doesn’t work. His future? Not great. Mike Bloomberg says everything is fine. What do you think?

EVELYN HERNANDEZ: There you go.

ANDREW WHITE: And you have the radio voice too. Impressive.

EVELYN HERNANDEZ: I think one of the most outrageous ads that I’ve seen in this campaign season is the one where Mike Bloomberg tells us that he remembers when he came to New York 40 years ago and how expensive housing was. And I’m like: “Yeah, and it’s been that long since you’ve had to think about it. Right?” About how expensive housing is. That is the most audacious…talk about nerve.

HANK SHEINKOPF: The better ad… “They are having big parties in Manhattan these days. The red rope is there. People are getting into discothèques, living the high life but not here in Maspeth.” The point I’m trying to make is if you want to win campaigns you have to personalize the argument in an emotional context that relates to the people you’re talking to. This attempt to rationalize irrationality…is not helping them. They are not going to get it because they don’t understand the emotionalism involved. They are talking it but that’s not what gets people to respond.

EVELYN HERNANDEZ: Right. And to extend the two cities theme, talk about – we are not talking about poverty in this campaign at all. The poverty rate has gone up during this campaign. Fully 20% of the people living in this city, live in poverty. We are not talking about that. We are not talking about unemployment, under-employment. We are not talking about the fact that the development – whatever proposals we have – these big development plans, they give all sorts of great breaks to big developers like Michael Bloomberg and there is no job plan, no training component for people so that the average person can get a job in one of these. We are losing middle class housing, Mitchell Lama is going offline. Those are very emotional issues. People are pissed off about that. And yet, it’s true, Ferrer has not tapped into that anger. He’s being too nice and too polite and it’s going to cost him the election.

ANDREW WHITE: Although I’ve got to say it’s interesting to see, even in this room, we can make Bloomberg out to be a plutocrat, just because of his wealth. Not so much because of the policies that he has been implementing for the last four years.

HANK SHEINKOPF: I’m not casting judgments on him.

ANDREW WHITE: I want to get a couple of questions from the audience before we move to the next panel. So, have Bloomberg’s policies really favored the elite?

HANK SHEINKOPF: I’m not in the policy business, I’m in the politics business so I go about this differently. Policy – okay, who cares if they have? You want to win campaigns. I know that sounds awful but this is about winning and losing. Okay? You want to make this argument real? You got to make it real for people. These guys are talking in the abstract. Bloomberg puts up plenty of points. It’s moved his favorables. Freddy doesn’t have the money to put up plenty of points so find one argument that bashes everything else and some people pay attention. He’s not doing it. They are running a bad campaign.

EVELYN HERNANDEZ: I think Bloomberg is a good mayor and a decent man. I think that the policies deal with, as I said, they do seem to help a certain echelon of society and other people are being left out.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: There are two parties in the City. Do you feel that Freddy perhaps is not getting the full benefit of the party that he represented? A lot of the campaign issues that we are talking about, strategies, the mobilizations of the urban people that he should be reaching. I’m not getting the flavor that the party has mounted a New York City Democratic campaign that would further that goal.

LEE MIRINGOFF: So, first of all, Bloomberg is attracting about half the Democratic voters right now so that is going to neutralize a lot of the party leaders, in terms of understanding that their folks are very divided in terms of their own loyalty. But I am struck by the endorsements that Ferrer got by the major office holders, who obviously were not mentioning Bloomberg, or had no reason about why Bloomberg – talking about running against an incumbent by having some negative energy against something that incumbent does. And that we are not getting from the Democratic leadership. And neither did Ferrer get the Democratic money that traditionally comes in or was promised from the national leadership. Part of it has to do with the fact that the campaign didn’t get off.

HANK SHEINKOPF: Just one point. What party? The best of it, frankly, they are extraordinary people who have high principles. I count Dennis Rivera in that lot, who is an extraordinary labor leader. I just think he’s the best and he’s out there doing it and he’s doing it and he’s really the Democratic Party.

ANDREW WHITE: Who did you say?

HANK SHEINKOPF: Dennis Rivera, the head of 1199, Healthcare Workers Union, is an extraordinary guy. He’s out there doing it. So yes, people are doing it. Are they doing it with the same intensity as Rivera is doing it? Probably not.

EVELYN HERNANDEZ: There’s also a sense of inevitability that has settled over a lot of people and also there are a lot of Democrats in town who are thinking a little bit too much about 2006, 2008 and 2009 and haven’t really focused on 2005. And if they want to run for mayor in 2009, they are not really that enthusiastic to have Freddy win.

The other thing is that when you have a five to one ratio, you have to wonder – people tend to vote locally in New York, they vote for the person, not the party at this point. More and more. And I think that when it’s such a lopsided ratio, it stops meaning something after a while. It stops being a meaningful matter, after a while, that you have Demoolor, competence is always that little question mark, that can be raised. Can he handle it? It is raised around the country. You will see black candidates and Latino candidates will have their, “Are you qualified?” “Is he qualified?” “Can he handle it?” “Is she competent?” So that’s always an issue that as a candidate of color you are going to be scrutinized more in that area. Even though people will deny it and say that’s not fair. We are just asking the question and we would have asked it if he was white. Baloney.

ANDREW WHITE: Not to deny the importance of that, but also I think as a Democrat, people are called into question now nationally, in politics, competence, as Democrats.

But we are going to have to move to the next panel.

EVELYN HERNANDEZ: I think George Bush has changed that equation. (laughter)

ANDREW WHITE: So, thank you to this panel. Hold on, we are going to bring on another group. We will introduce our next moderator, who is Jon Bowles, the recently appointed director of the Center for an Urban Future, though he has been there for many, many years.

JONATHAN BOWLES: Thank you so much. Thanks to the panel for the previous session. It was fascinating and I think we have another great discussion lined up for you right now.

I’m Jonathan Bowles and I’m the director of the Center for an Urban Future. If you don’t know, the Center is a nonpartisan, independent policy institute that writes studies about economic development, workforce development, higher ed and a couple of other issues that are critical to New York’s future. We are the sister organization of City Limits magazine, which has been around for about 30 years now, writing about urban affairs issues in New York.

Just quickly, with this panel, we are going to try to move the discussion from the politics of getting issues into the campaign debate to the most pressing policy issues that City Hall will have to confront during the next four years. And how each of the candida