School reform has been a top priority for the Bloomberg administration ever since the mayor took office. But it wasn't until this year that Mayor Bloomberg and Chancellor Klein took aim at one of the most overlooked and underfunded parts of the school system — vocational education, now known as career and technical education or CTE.

A task force convened by the mayor earlier this year just released its final report on July 30, calling on the city to transform CTE into "a desirable, respected, and accessible option" for city students.

In an era when "college for all" has become the universal goal and high-stakes standardized testing has taken hold as the measure of success or failure, CTE might not seem to have a place in the public high school of the 21st century.

But the numbers don't lie: a May 2008 report I authored for the Center for an Urban Future showed that 64% of New York City's CTE students in 2002 — students who began high school that September — had graduated by October 2007, compared to 50% of the non-CTE high school students in the five boroughs who graduated. Over the same period, the dropout rate among CTE students in the city was 5%; for non-CTE students it was 20%.

These vocational schools produce superior outcomes in spite of drawing disproportionately at-risk students, and groom young people for decent-paying jobs in occupations that are now in high demand, from automotive technicians to opticians.

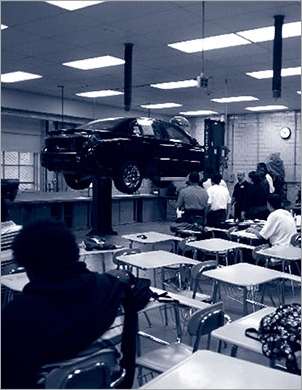

The secret to CTE's success is that the courses engage students to a much greater extent than typical classroom fare. Research has shown that a large portion of those who drop out from high school do so because their classes seem boring and meaningless. At its best, CTE not only holds their interest, but also furnishes them with real world, in demand skills for which employers will pay well.

The city is home to a number of standout CTE schools, such as Aviation High School and Thomas Edison High School, both in Queens, and Manhattan's High School of Fashion Industries and Food and Finance High School. But the quality of New York's 21 CTE high schools is far from uniform, and CTE enrollment overall has dipped in recent years.

Programs have suffered from years of inattention and indifference on the part of city education officials, who have failed to provide schools with sufficient resources to pay for up-to-date equipment and training tools.

Commendably, the report released last week by the mayor's task force grapples with most of the major problems facing the city's CTE schools. In particular, it highlights lingering — and false — negative perceptions around "voc ed" as a lesser academic track for students who can't handle demanding schoolwork. The report also identifies the absence of integrated curricula to inculcate both core academic competencies and career-related skills, and the "disjointed" nature of engagement with the private sector — a vital partner in any successful CTE effort.

The report also is clear about how New York City and State must work together around defining new competencies, adjusting requirements for the amount of time spent in class, and other key areas of collaboration.

Unfortunately, the task force is more powerful in its diagnosis than in its prescriptions. Perhaps the biggest shortcoming is a lack of candor and detail about what it will cost to implement the suggested reforms. As just one example, the report urges the city's Department of Education to "[support] principals and teachers to redesign and create new courses and adapt new teaching methods ... [and provide] appropriate, ongoing and embedded professional development ... ." But none of that is free, and the Department has not shown great facility in delivering this support in the past. This is a goal, not a plan.

With few exceptions, such as the calls to develop "an inventory of existing partnerships linked to CTE schools ... to provide a baseline from which to gauge the effectiveness of new efforts," and for "defin[ing] quantifiable targets for internship development across schools/programs," this absence of specifics characterizes the report. Moreover, there is little sense of how city officials and other stakeholders will know if reforms are working. In part, the problem is that this effort comes so late in the Bloomberg administration: the report calls for a five-year CTE Strategic Plan, but the last four of those years will unfold with a new mayor and, presumably, a new chancellor in charge.

Given the high profile of the effort — the task force was co-chaired by a former New York mayor, David Dinkins, and the chief executive officer of New York Life, Sy Sternberg — and commitments from business leaders, CUNY, the state Board of Regents, and other key players, the stars seem aligned for a needed overhaul of CTE. The risk is that with no strong follow-up plan and too little detail on what is to be done, a failed effort at reform will ensure many more years of underperforming programs.