What Ails Workforce Development and How to Cure It

For Americans who seek preparation for the middle-skill workforce, the following institutions offer assistance in connecting with employers and climbing the career ladder:

-

One-stop career centers were established and funded through the 1998 Workforce Investment Act (WIA) in every local labor market in the United States. One-stop centers provide a wide variety of services to jobseekers, including job matching, career navigation, resume preparation, and eligibility for training vouchers.

-

Community and technical colleges provide instruction toward an associate’s degree, prepare students for transfer to four-year colleges to earn a bachelor’s degree, provide training toward industry-recognized certificates, and, in fourteen states, oversee all or some of the adult education system.

-

School districts manage workforce-oriented career and technical education programs at local high schools and, in the majority of states, oversee adult education services.

-

Community-based organizations provide a wide array of services to meet the needs of their local communities, including job training, adult literacy, soft skills development, and sectoral pro-grams that merge multiple services under one roof.

-

Beyond these providers, there are still others: proprietary colleges, apprenticeship programs, and workplace training sponsored directly by employers.

Despite their accomplishments, workforce providers in the United States struggle to have an impact. The patchwork assemblage of services available in most regions does not gel into a coherent system that effectively meets the needs of local residents and employers. At the local level, workforce providers find themselves spending the majority of their operating budget just to keep the lights on, preparing clients for new occupations without enough information on job availability, serving experienced adults who could probably find a job without assistance, and trying to clarify a confusing tangle of service options to jobseekers.

Most of the developed world does a better job at preparing their workforces with middle-skill degrees. The United States is second only to the Netherlands in the share of its population with bachelor’s degrees. But for middle-skill degrees, the United States ranks poorly, at sixteenth. The United States has the highest college dropout rate in the world, but again, the problem is concentrated in the area of middle-skill degrees. Only 28 percent of students who enroll in middle-skill degree programs graduate on time.

Although more money spent does not necessarily imply higher quality, other developed countries devote far more available resources to their workforce-development systems than the United States. In 2010, the average developed nation spent about 0.7 percent of GDP on active labor market policies, while the United States spent only 0.1 percent of GDP. This differential has remained stable over time.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which collects data on active labor market policies that are “geared toward enhancing the employment and long-run earnings prospects of unemployed workers and those with low skill levels,” has found striking differences between the United States and other OECD nations. Germany’s elaborate vocational training system receives frequent attention. Researchers have found that most west European countries, as well as Canada and Australia, have employment and training systems that are more “comprehensive and stable” than the United States. Germany and the northern European countries, in particular, have integrated apprenticeships into the fabric of their workforce systems, building broad employer-labor agreements that provide clear career paths to young adults, with the systematic training and mentoring needed to accomplish them.

Workforce services in the United States fall short along several dimensions. Many providers are not serving the disadvantaged who would benefit the most, while those who do serve the disadvantaged may be financially penalized. Engagement with employers, the most essential component for effectively targeting services, remains inconsistent and too often at a level that provides only modest benefit either to employers or the unemployed. The main funding streams from the federal government are disbursed without any broader vision, siloed by conflicting outcome measures and performance standards, as well as state and local implementation that mirrors fragmentation at the federal level. Workforce-development professionals struggle to reform their profession within the context of steadily dropping public investment, which throttles the capacity for flexibility and innovation.

There is a vital need for the federal government to overhaul workforce and welfare legislation passed during the late 1990s, develop overarching principles for organizing its human capital investments, and strengthen its investment in effective workforce strategies. Reshaping and strengthening the federal role in workforce development is the most essential precondition to building an effective and coherent human capital system.

INEFFECTIVE TARGETING OF THE DISADVANTAGED

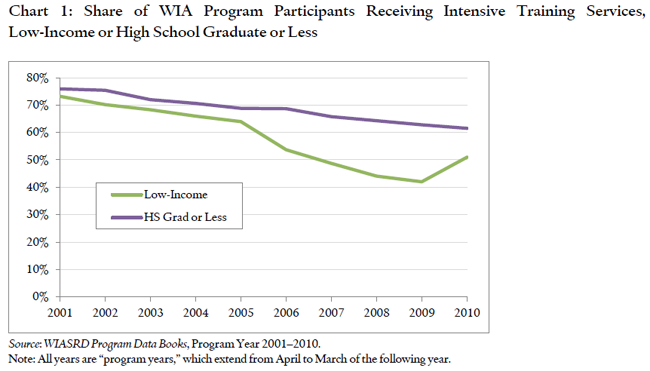

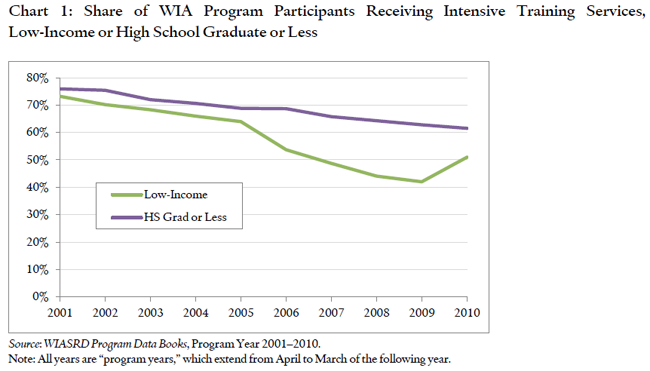

Workforce programs have drifted apart in the populations they serve, with some focusing on the most disadvantaged and others cherry-picking clients who are easier to help. The 1998 Workforce Investment Act abandoned the poverty-reduction focus that characterized previous workforce programs in favor of universal access to all applicants, reflecting arguments that a broader mission would make workforce programs more attractive to employers. This strategy, whatever its merits, has resulted in a rebalancing of services away from low-income clients. In 2001, 73 percent of clients receiving WIA intensive or training services were low-income; by 2009, only 42 percent were.22 In 2001, 76 percent of clients had earned no more than a high school diploma; by 2010, that share had fallen to 62 percent. The median workforce client continues to be disadvantaged, but provider emphasis is clearly shifting away from the disadvantaged.

According to interviews with service providers and workforce experts, the main forces driving WIA-funded Workforce Investment Boards away from the neediest clients include declining federal funding; the WIA performance measurement system, which pushes providers to continually place large numbers of clients in paid employment; and the demands of employers, who have become increasingly resistant to taking on workers likely to need additional training after hire.

Community colleges generally succeed in serving disadvantaged adults by taking all applicants at a low cost. But the notoriously low community college graduation rate suggests the disadvantaged are screened out in other ways. The majority of community colleges have yet to confront weaknesses in developmental education, academic advising, high school alignment, and other supports that ensure students complete their studies. As noted earlier, a large proportion of adults lack the foundational and workplace competencies employers expect. Community colleges play a crucial role in serving those less-prepared adults, but they could do a better job.

The migration of services toward job-ready or college-ready clients reduces the value of the most visible service providers. In addition, these providers are less likely to coordinate services with other workforce-related programs that continue to serve disadvantaged clients with serious barriers to employment or postsecondary completion.

EMPLOYER ENGAGEMENT REMAINS INADEQUATE

Few workforce providers in the United States are fully engaged in meeting the needs of employers and boosting their local labor market. This remains true despite the fact that the last major workforce reform focused primarily on making workforce providers more responsive to employers. The 1998 Workforce Investment Act (WIA) established regional Workforce Investment Boards with mandated employer representation, and required them to report the number of clients placed in jobs annually. The states and localities had to develop systems to track job placement and retention rates, which became the main yardsticks of effectiveness. States that fell short of their placement and retention goals would attract federal scrutiny and lose the opportunity to receive special incentive funding. States and localities responded by holding their contractors accountable for the same measures, often with performance-based contracts.

Similarly, the 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reform Act prioritized “rapid work attachment” and required states to keep a fixed percentage of welfare recipients in work activities, even if that meant mandating their participation in useless busywork. States who pushed their clients into jobs and off the welfare rolls would be financially rewarded, without tracking the clients into the workforce to see if the work experience provided had any lasting value.

In theory, all this attention to putting clients in jobs was supposed to serve the needs of employers. It does, but in an ephemeral way. From an employer’s perspective, filling positions through a one-stop career center or a community-based organization can improve the efficiency of a hiring process. But employers can make use of other services and technologies to perform the same function. The value of using a publicly funded job-matching service is primarily its low cost, but that must be weighed against the trade-offs—bureaucratic procedures, eligibility restrictions, and a large quantity of paperwork to fill out—all of which discourages smaller businesses from participating.

The more pressing concern employers express is getting applicants with the right mix of vocational, literacy, and workplace skills. Increasingly, employers resist training new employees themselves, yet they also lack strategies to signal their workforce needs and get them met in a systematic way. Applicants with the needed skills are hard to produce in a workforce system devoted to rapid job placement.

There is little evidence available that specifically pertains to the types of workforce services employers value, but one good proxy is to look at the earnings and employment gains achieved by various kinds of workforce services. A study by Washington State found that short-term training courses provided little in the way of an earnings boost. But students who took at least one year’s worth of courses and obtained a credential with value in the market reached the economic “tipping point,” obtaining an income boost ranging from $1,700 to $8,500 annually. Investing small amounts in an unemployed adult yields a small return on investment. Investing generously with guidance from employers yields a much larger return.

Postsecondary training toward certificates, certifications, and associate’s degrees has a higher pay-off than short-term workforce interventions, yet the institutions that provide that training are not always as energetic and savvy about engaging with employers as they should be. In particular, community colleges often lack strong partnerships with employers to inform their course offerings and programs of study. They could gain valuable intelligence from real-time labor market information databases, but few community college leaders make use of these services, even in continuing education.

As employers increasingly emphasize skills and credentials, workforce providers continue to put far too much energy into connecting clients with the first available job. As a result, they often fail to hear and respond to the clear signals that employers are sending. Meanwhile, educational providers give employers a deeper level of service, but may not have close-enough relationships with employers to keep up with their needs.

INNOVATIONS THAT WORK

Where the United States excels is in creative employer-engagement programs at the local level, as well as external evaluation of those programs. The most promising strategies being tested include the following:

-

Sectoral partnerships between employers and providers. A sector partnership focuses intensively on a specific industry in a regional labor market. Instead of trying to serve all employers in a region, sectoral workforce providers develop industry-specific expertise and durable relationships with employers in that sector. For example, Per Scholas in New York City trains young people to work as computer technicians for IT companies. Per Scholas offers a 15-week, 500-hour training program leading to an A+ certification, and includes support in workplace skills such as communication, time management, and interviewing. One study of three sector partnerships, including Per Scholas, found that participants earned 29 percent more than the control group over the next year, or about $4,000 annually.

-

Career pathways. A career pathway is a framework that alternates educational opportunities with employment in a connected and deliberate way. In a high-functioning career-pathway system, workforce practitioners collaborate with employers and education providers to develop a road map that shows clients their next employment steps and what will be required to achieve them. A student interested in construction technology, for example, who enters Rogue Community College in Oregon might start by earning a certificate as a Computer Assisted De-sign (CAD) assistant, then find employment as a drafter assistant or CAD operator assistant, then return to college for an Architectural CAD certificate, obtain a higher-paid job as a CAD drafter or architectural assistant, return to college for an associate’s degree in Construction Industry Management, and so on. States that have implemented sophisticated career-pathways systems include Oregon, Washington State, Arkansas, Kentucky, and Wisconsin. The U.S. Departments of Labor, Education, and Health and Human Services collaborated on a 2012 joint letter announcing their commitment to promote the use of career-pathways approaches as a promising strategy to help adults acquire marketable skills and industry-recognized cre-dentials.

-

Combining adult education with occupational training. The traditional educational path goes through high school and focuses on improving both college enrollment rates and college read-iness among high school graduates. But high school dropouts face much steeper odds. Even af-ter obtaining a high school general equivalency degree (GED), they are extremely unlikely to obtain any postsecondary credential. Washington State providers found a way to even the odds for adult students by enabling them to participate in both occupational skills training and adult education services at the same time. Typically, a student enrolls in a class co-taught by occupational and adult education faculty; they collaborate on a curriculum (e.g., allied health) in which foundational skills are taught in the context of an occupation, and occupational vocabulary and concepts are embedded into foundational skills instruction. Studies have found that students enrolled in the program, I-BEST, are more likely to graduate and earn more after graduation.

These local workforce programs are mostly young by the usual standards of labor market interventions, yet a growing body of research is finding them effective. Unfortunately, they represent islands of innovation in a status quo sea. The urgent need is to develop, test, and bring to scale these and other evidence-backed innovations around the country.

THE FEDERAL ROLE IN WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHY IT FALLS SHORT

The missing glue in the U.S. national human capital system is the federal government. Despite the remarkable innovations that have taken place in a few states and localities, those innovations will remain isolated and vulnerable to backsliding without a strong federal role. At its best, the federal government can support the development of best practices and spread them across state boundaries.

The federal role is especially important in the development of human capital. Unlike states and localities, the federal government can fund programs that cross jurisdictional lines and support populations that may be disfavored at the local level. For example, local governments are historically reluctant to provide workforce services to migrant workers who do not settle in the communities where they work. The federal government can also commission cutting-edge research to develop the evidence base for effective programs and then incorporate that research into the actual programs. Finally, the federal government can sustain innovative programs in a way that state and local governments find both fiscally and politically difficult.

The federal government’s investments should align within a common vision to reach their maximum potential. That is far from the case today. In 2009, the U.S. Government Accountability Office found forty-seven different workforce programs spanning nine federal agencies, of which forty-four serve overlapping populations. This influential report has prompted proposals to turn all federal workforce programs into block grants to the states, which would essentially eliminate the federal role in workforce development. A block-grant system would frustrate the essential role that the federal government should play: supporting best practices in employer engagement, targeting services to the disadvantaged, and identifying and spreading evidence-backed best practices.

As is, the federal role in the workforce shrinks year after year, nibbled away by budget cuts. Adjusted for inflation, WIA workforce funding dropped by 59 percent from 2000 to 2010, even as the number of unemployed Americans who could benefit from those services more than doubled. The stalemate over sequestration will cause an additional 2 percent cut in federal workforce funding in 2013, with more to come.

The impact of steadily deteriorating funding has been to force the workforce field into a reactive crouch. Providers find themselves spending most of their budgets on modestly useful services for which they are held accountable, notably job search and placement. Occupational training has be-come a residual use of funding, because required services absorb almost all of their budgets. In 2008, only 9 percent of the one million adults served by the federally funded workforce system obtained a credential of any kind.

Community colleges have done a better job of protecting their operating budgets, but they too are losing ground. The most important federal support for community colleges, the Pell grant, has lost much of its value relative to tuition over the past two decades. During the Obama administration, Pell grant funding has grown, partially reversing the ground lost in previous administrations. Unfortunately, Pell eligibility has also eroded for working adults. Congress reduced the number of semesters students can qualify for Pell, eliminated access to students in programs that integrate preparation for a high school equivalency with college enrollment, and revoked Pell grant availability in the summer semester only a year after launching it. These provisions may seem like the stuff of financial aid wonkery. But working adults have a much harder time getting and using financial aid, and without it many are forced to drop out of college.

A smarter strategy would see the reinvention of workforce development in the United States, enabling the federal government to fulfill a unifying national role while stepping out of the way of state and local governments as they develop innovative strategies tailored to their respective labor markets.