Gov. George Pataki's state budget proposal has drawn attention for the bad news it doles out to commuters, city schoolchildren and a host of other groups.

But one constituency he didn't mention that absorbs more than its fair share of the pain is the state's half-million plus low-income working families, who face the prospect of higher college tuition rates at state schools, withholding of state aid to pursue a college education and changes to Medicaid that could limit health care.

Despite some positive measures as well and the state's proven commitment to policies that "make work pay," the governor's budget continues the state's frustrating pattern of pairing every step forward with a step back when it comes to policies affecting this hard-pressed group.

We're not talking about the homeless, the chronically unemployed, or other demographic groups that might be defined as "the truly needy." Rather, these are people with jobs and homes; they don't generally miss meals. As President Bill Clinton once put it, they work hard and play by the rules. But despite all their efforts these New Yorkers are losing ground.

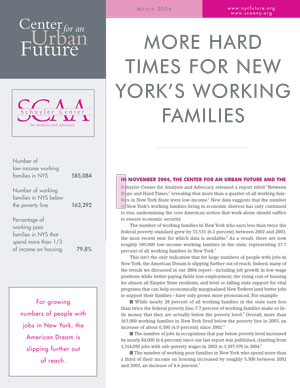

Last fall, our two organizations released a report on this group, titled "Between Hope and Hard Times: New York's Working Families in Economic Distress." We found that more than 550,000 working families in the Empire State don't earn enough through their jobs to be self-sufficient. About one in 12 working families is below the official federal poverty line.

A majority of these families live in New York City, though low-income working families are found across the state. Certain realities of urban life tend to exacerbate their plight, including the high cost of living, the severe shortage of affordable housing and the large number of immigrants without high-end job skills.

But perhaps the most obvious explanation why all these New York families live in the grim shadow of poverty is that many jobs here just don't pay much: despite the rhetoric of New York as a high-wage, high-skill state, 32 percent of all New York jobs pay low wages.

With so many jobs paying little, there's a limit to how much benefit New York's approach of "making work pay" can bring. The state deserves credit for refunding some $677 million to taxpayers through a very generous and well-run state Earned Income Tax Credit. Other tax measures, from the personal income tax to credits for education and childcare, provide additional assistance to working families. State subsidies and programs for day care and health care benefit millions of New Yorkers. Phasing in the newly increased minimum wage will help, too.

New York deserves praise for its best-in-the-nation commitment to need-based financial aid for college students. But tuition costs at public institutions of higher learning like the State and City Universities of New York were rising faster than resources for assistance even before the governor's latest proposed changes. Community colleges in New York have been slow to change their policies to help the rapidly growing number of adult and part-time students looking to increase their earning power. Adult education--especially programs to improve immigrants' English literacy and speech--is under-funded and not well connected to the job market.

New York's economic development initiatives should do a lot more for low-income workers as well. Currently, large corporations are awarded subsidies with no stipulations about job creation. As has been reported in the press, the state's Empire Zones program--specifically designed to foster economic activity in distressed areas--has largely foundered on the shoals of mismanagement and political manipulation. The economic development strategy that could most directly benefit both workers and employers is business-designed training for workers already on the job. In many states, this is a bulwark for growth, but it has become a political football in New York.

The problems of low-income working families are complex. There's no single-bullet solution. To provide quality education, job skills training, affordable and stable housing, and economic growth, business, government and community-based organizations must join together. This more holistic, collaborative approach to helping struggling workers is not something that comes naturally to the public sector, but it can be done. The philanthropic community in particular has begun to assess poverty issues more broadly to assist working poor families from a variety of angles. We must affirm that hard work and determination--traits displayed daily by more than half a million low-income workers in our state--really do blaze a trail toward prosperity.