In recent years, New York City and State policymakers have made k-12 education reform a top policy priority and invested significant resources in universal pre-kindergarten. This focus makes perfect sense given the increasing value of education in today’s economy. But with so many adult New Yorkers also lacking the basic literacy and educational skills for which today’s employers clamor, it’s time for policymakers to also take steps to improve adult education.

"Boosting Adult Education in New York" is part of a series of commentaries about workforce development and human capital issues funded by the Altman Foundation. Funding was also provided by the Working Poor Families Project, a national initiative supported by the Annie E. Casey, Ford, Joyce and Kresge Foundations which partners with nonprofit organizations in 22 states to investigate policies that could better prepare working families for a more secure economic future.

General operating support for the Center for an Urban Future is provided by the Bernard F. and Alva B. Gimbel Foundation; with additional support from the Lucius N. Littauer Foundation and the M&T Charitable Foundation.

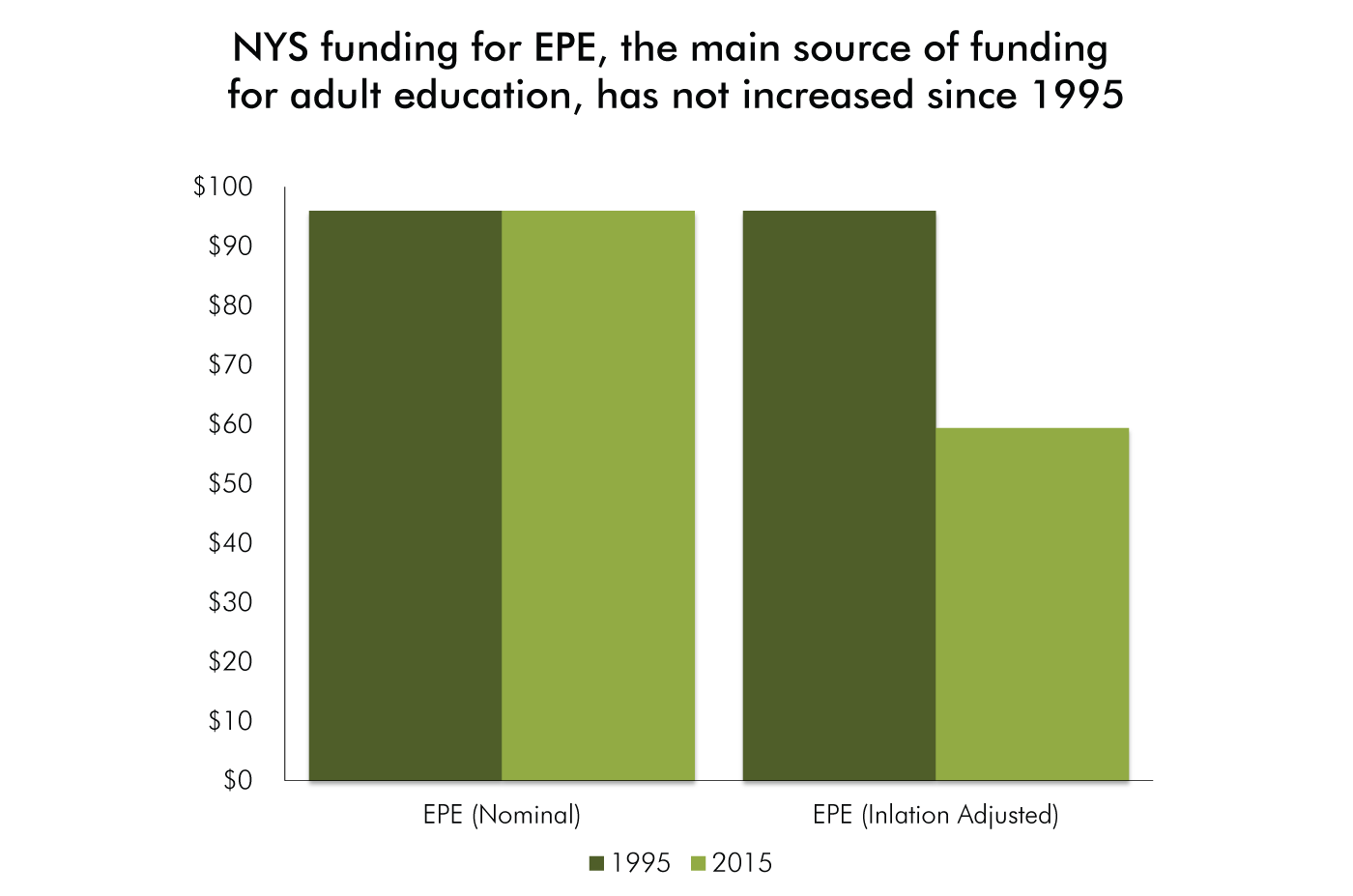

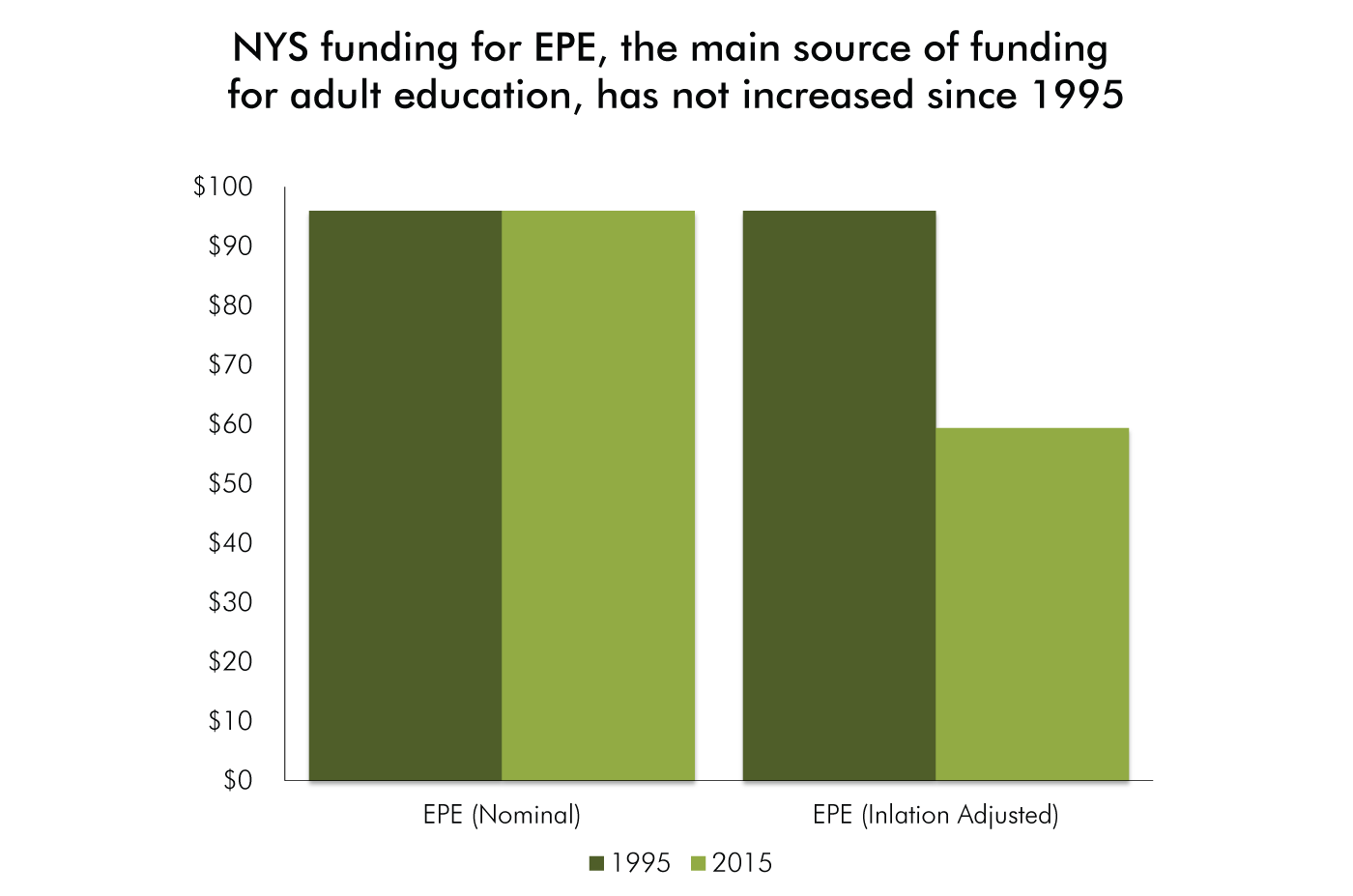

For too long, adult education has gone overlooked in discussions of economic and workforce development in New York. As just one indication of the state’s neglect, the main funding source for adult ed programs in the state has not been increased since 1995, even though the number of adult New Yorkers with limited basic literacy skills—and the number of immigrants with limited English proficiency—has skyrocketed over the past two decades.

All this needs to change. In New York State, 1.6 million adults lack a high school diploma or equivalency (12.5 percent of all adult New Yorkers) and 1.8 million adults across the state do not speak English well or at all.1

These numbers are alarming in an age when most well-paid jobs available to adults with modest skills and educational attainment have already been automated out of existence or shipped overseas. Without a skills boost, most of these adults will be stuck in low-wage, dead-end jobs. Meanwhile, many of the state’s employers will struggle to attract the workforce they need to remain competitive.

The way forward is through an integrative strategy called “career pathways” developed by the nation’s leading human capital experts. The career pathways framework coordinates education, training and social services providers in an employer-responsive continuum that makes sense to jobseekers, aspiring workers and service providers. One crucial element of an effective career pathways framework is adult education. With a few long-overdue changes, the adult education field could boost New York State’s economic prosperity by preparing low-skilled adults to acquire the skills that will qualify them for the jobs employers urgently need to fill.

New York has a primarily publicly funded adult education system to provide instruction to adult learners. The diverse community of service providers contributes extremely valuable and essential services to adult learners and disadvantaged communities. But the system as a whole suffers from two crippling defects—underfunding and poorly structured financing and provision of services.

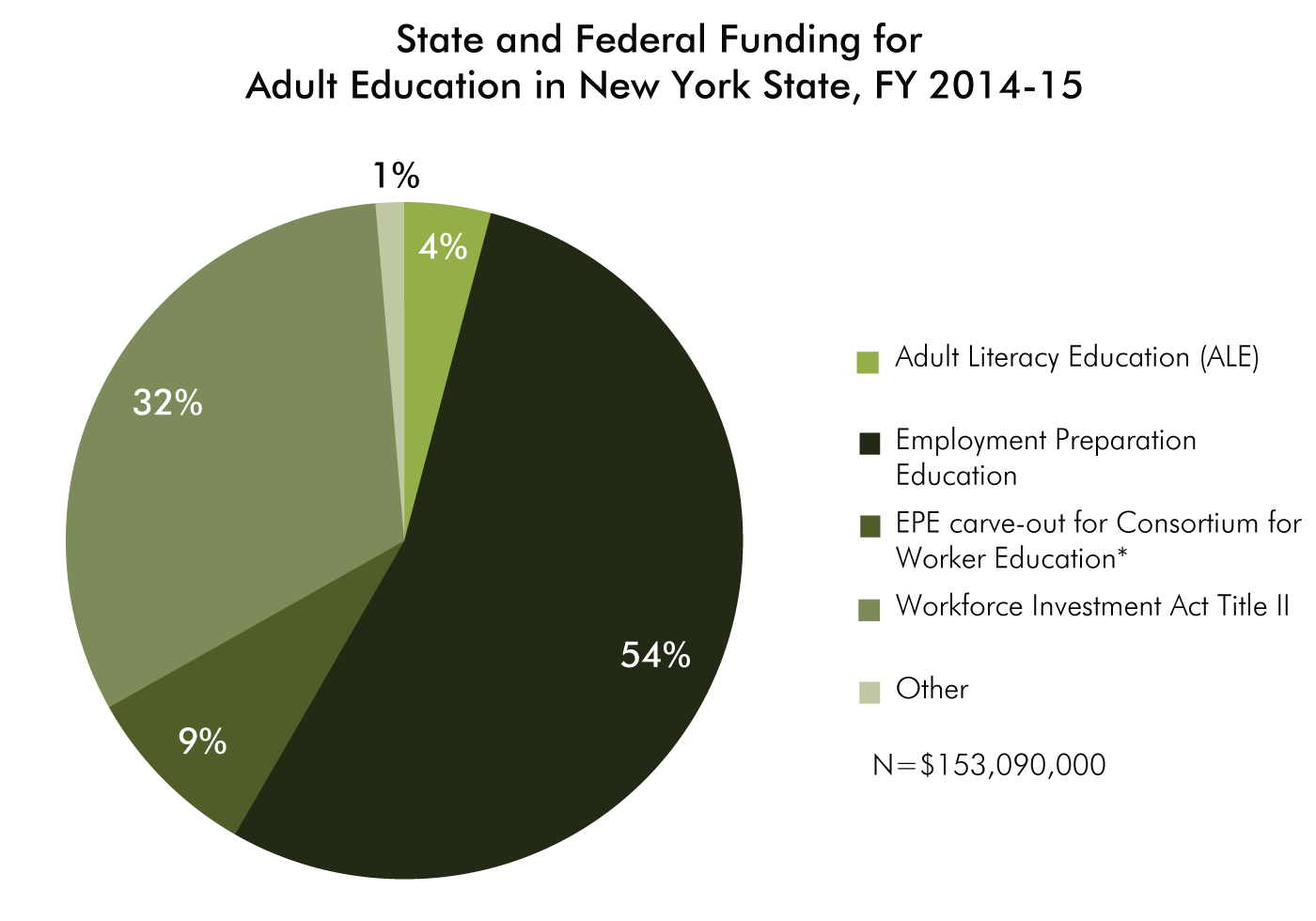

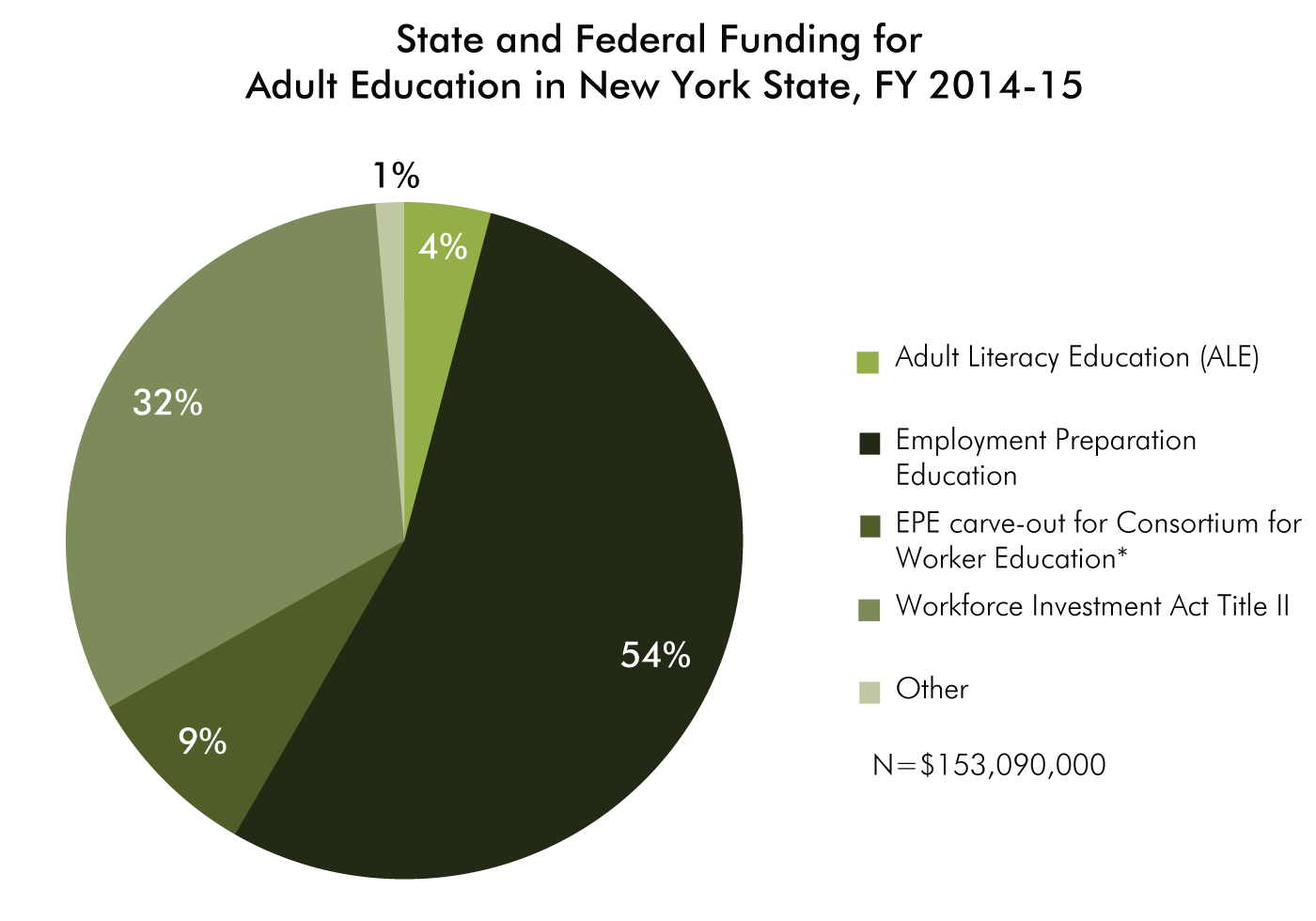

The largest funding source for adult education in New York State is a program called Employment Preparation Education, or EPE, which was allocated a funding source of $96 million in 1995—generous at the time, compared to most other states. Incredibly enough, however, funding for EPE remains at $96 million in 2015, even as inflation has driven up prices for the economy as a whole by roughly 55 percent during this time and the number of New Yorkers who could benefit from adult education programs, including English language programs, has increased dramatically. (For instance, between 2005 and 2013, the state’s foreign-born population increased by nearly 400,000 and the number of immigrants needing English instruction jumped by 14 percent. During the same period, the number of state-funded seats for English instruction fell by 32 percent.) Today, New York ranks only 18th among all states in its per-adult funding for adult education.2

Source: New York State Department of Education and Bureau of Labor Statistics

Inflation adjustment is converting 2015 dollars into 1995 dollars.

The other primary adult ed funding sources, New York’s Adult Literacy Education (ALE) program and the federal Workforce Investment Act Title II programs, have stagnated as well. The philanthropic community is seeking to fill some of the gap, but they lack the resources to meet more than a tiny fraction of the unmet need.

Source: Seeking a State Workforce Strategy, David Jason Fischer and Melinda Mack.

* The Consortium for Worker Education provides a spectrum of work-related skills training of which adult education is only one component.

The adult education financing and governance system is also poorly structured to serve adult learners most effectively. Collaboration between providers is unfunded and uneven, so most students do not get the benefit of services such as career counseling or occupational training unless they have access to integrated adult education and workforce services at an entity that provides them. New York funds adult education providers on a simple fee per instructional or contact hour basis: $8 per student per hour of instruction. This sends providers the message that they should offer services as cheaply as possible – even if it means accepting poor outcomes. Most adult education instructors are part-time, with little access to professional development, which limits their ability to provide comprehensive services that lead to quicker and steadier learning progress.

Adult education in New York needs a higher profile and fundamental rethinking. An invitation to do just that arrived last year with bipartisan passage of the federal Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act of 2014 (WIOA). This federal law replaces the Workforce Investment Act, the main federal funding vehicle for adult education and workforce development. WIOA seeks to dramatically improve the connections between adult education and employment and training providers. States are expected to explain how their various programs—which at present work independently of one another as a rule—coordinate their activities in the future. In New York City, the de Blasio administration gave the WIOA strategy powerful momentum by developing a very similar blueprint for coordinating the city’s education, workforce and supportive services to meet the needs of employers, aspiring workers and local communities.

The basic organizing principle for both WIOA and New York City’s workforce development rethink is called “career pathways,” an approach for connecting progressive levels of education, training, support services and credentials to optimize the progress and success of individuals with varying levels of abilities and needs. Career pathways connect occupational education and training and employment in a given economic sector. Individuals can enter at multiple points to obtain education and training services, exit at multiple points to work at the jobs for which they have been prepared, and enter again to obtain the education or training necessary for the next step on the pathway.

Most programs that begin career pathways require foundational skills such as math, reading, writing and English language proficiency at the high school level, or higher. Low-skilled youth and adults will lose these opportunities for upward mobility unless they can strengthen foundational skills. That’s where adult education providers, with their deep understanding of foundational skill development, come in. A handful of evidence-based models, such as integrated education and training and bridges to careers, have shown how adult education providers can collaborate with workforce and postsecondary providers to dramatically improve adult learners’ career prospects. Community colleges in particular have done a good job of testing and scaling collaborative instructional models, both in New York and across the country.

What could the future of adult learning in New York look like? Policymakers should rebuild the state’s adult education system to support four core principles, similar to those being used to reform career and technical education at the federal level.

-

Alignment: Adult education instruction can be more effective if it aligns with the goals adult learners have after leaving the program, such as gaining employment, getting a better job, or obtaining a postsecondary credential. Developing new models and incentives that pave the road from adult education to learners’ goals is crucial. A key first step is learning more about what skills employers need from workers, both directly and from labor market information analysis. Other strategies might include allowing adult learning programs to continue working with students after they obtain a high school equivalency, which is currently prohibited for almost all EPE-funded students, and developing partnerships with community colleges so that exit exam results of provider programs are accepted for purposes of college placement.

-

Collaboration: Strong collaboration between adult education programs and providers in related fields, as well as the employer community, makes instruction more relevant, brings valuable new resources to adult learners, and connects adult learners to rigorous work-based learning opportunities. At present, few such collaborations exist. New York has created a Literacy Zone model that enables adult education providers to refer their students to other resources. In New York City, the Adult Ed Compass program refers jobseekers who visit workforce one-stop centers to a website that will help them find high school equivalency preparatory courses with openings.Yet so much more could be done. Collaborations with workforce providers enable students to obtain career counseling services and get on a career pathway. Collaborations with community colleges would ensure curriculum alignment and college readiness. Collaborations with career and technical education institutions could provide access to instructional equipment and facilities after school hours. One strategy to foster such collaborative relationships would be to require or incentivize EPE applications from multi-sectoral partnerships. The state could also fund demonstration programs to implement and evaluate collaborative models.

-

Accountability: Adult education programs should be accountable for producing meaningful results for adult learners. At present, the main outcomes that providers must meet are improvement in literacy and numeracy proficiency levels, as well as attainment of a high school equivalency. But the outcomes of publicly-funded programs should have a strong relationship to the aspirations of the clients being served, and these outcome measures are not the ultimate goal of most adult learners. Rather, they seek a new or better job, a promotion at work or a foothold to an upwardly mobile career. The state should reform EPE by exploring and implementing creative accountability strategies that reward high-performing programs and assist low-performing ones that need additional technical assistance and support. In addition, the state should develop common metrics and definitions connected to the new WIOA outcome measures that align adult education, career and technical education, workforce development and college readiness.

-

Innovation: New York needs to increase its emphasis on innovation in all human capital programs, including adult education. At present, the state has not prioritized innovation in any explicit way, and some elements of key programs actually discourage innovation, such as EPE’s formula funding (that is, all existing providers are entitled to funding rather than competing for it) and funding eligibility limited to local education agencies. Strategies that accelerate learning, such as hybrid learning and integrated education and training, urgently need to be tested, perfected and moved into mainstream practice. Policymakers should look to other states, notably Minnesota, Kentucky, Indiana and Washington State, that have adopted innovation-friendly adult education and workforce approaches.

The first step is always the hardest. Fortunately, a good starting point is already at hand. State agency leaders are in the early stages of preparing a proposal to submit to the federal government by March 2016. This “combined plan” will explain how the state’s key workforce, postsecondary and adult education programs will coordinate to implement WIOA. The combined plan represents a uniquely valuable opportunity to start a dialogue about the adult education system New York State needs, within the context of a vibrant and interconnected career pathways framework that boosts disadvantaged New Yorkers out of poverty, helps immigrants integrate into local labor markets, and provides employers with the educated and trained workers they need.

Right now the process of developing the combined plan is closed to stakeholder input. That’s a mistake. State policymakers should open up the design and implementation of the combined plan for engagement with outside stakeholders, as Congress intended when it enacted WIOA. This will foster the development of ambitious ideas that could be incorporated into the plan or a follow-up document.

New York is at a crossroads. The state can keep the fragmented system it has now, which provides adult education services to a small and declining fraction of those who need these supports, and without any real attention to what happens after they leave; or the state can take on the challenge of building a more comprehensive and effective system—a system built on the principles described above. Such a system would leverage existing resources to pull more people out of poverty and start them on a road to upward mobility and economic self-sufficiency. It would make a much more powerful claim on new public and private resources than the current one by showing concrete results for adult learners, low-income communities, employers and local labor markets.

There are certainly reasonable concerns about embarking on a process of structural change. But a system that goes too long without rethinking stagnates and loses effectiveness. New York has an opportunity to make adult education a vital component of a larger vision to serve adult learners, employers and the state economy. The state must seize that opportunity.

1 Working Poor Families Project. Population Reference Bureau, analysis of 2013 American Community Survey.

2 Working Poor Families Project. U.S. Department of Education, 2011–12 for dollars, and American Community Survey, 2011 for adults without HS/GED from PRB. Calculations use FY11 expenditures and 2011 population numbers.