This is an excerpt. Click here to read the full report (PDF).

The past two decades have been a period of almost unprecedented change in New York City. During these 20 years, New York has gone from crime-ridden to the nation’s safest large city, a remarkable boom in high-end condos has transformed the skyline, much of the waterfront has been redeveloped, and neighborhoods from Times Square to the Lower East Side have been altered so fundamentally that they are almost unrecognizable to anyone who last visited them in the early 1990s.

But in many ways, no other borough has changed as much as Staten Island.

On the most basic level, Staten Island simply grew the fastest. It far outpaced all of the other boroughs in the rate of population growth between 1990 and 2010. However, the borough’s rapid population growth is only the tip of the iceberg. Over the past 20 years, there have been far-reaching changes to nearly every facet of life on Staten Island.

This report takes a close examination of just what has changed. It provides the first comprehensive statistical analysis of the major trends that have shaped Staten Island over these two decades. Some of our statistical findings will be blatantly obvious to any Staten Islander who regularly drives across the borough at rush hour, takes classes at the College of Staten Island or operates a small business. But much of our data will come as a surprise. We hope it will also shed a light on several opportunities and challenges facing the borough over the next decade or two.

* * *

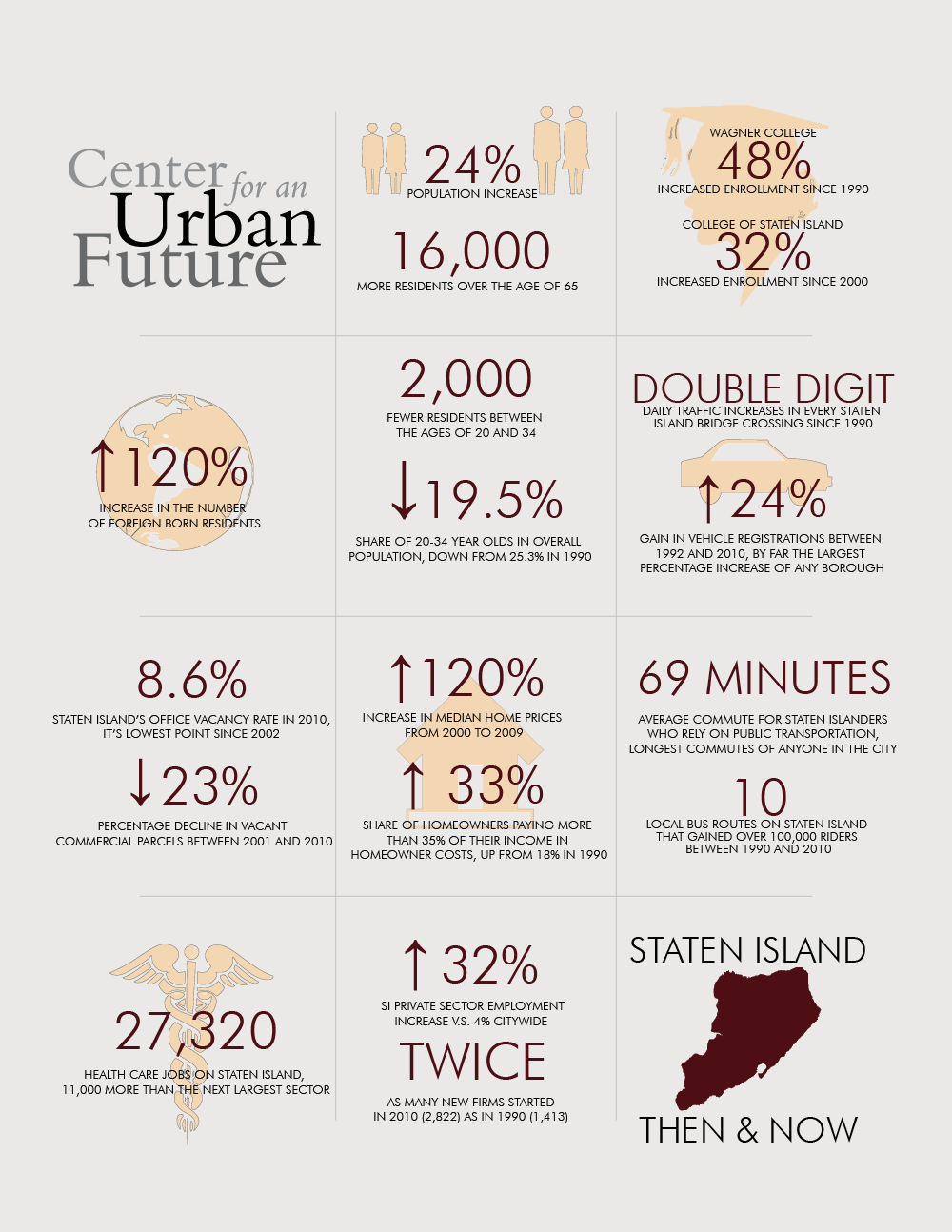

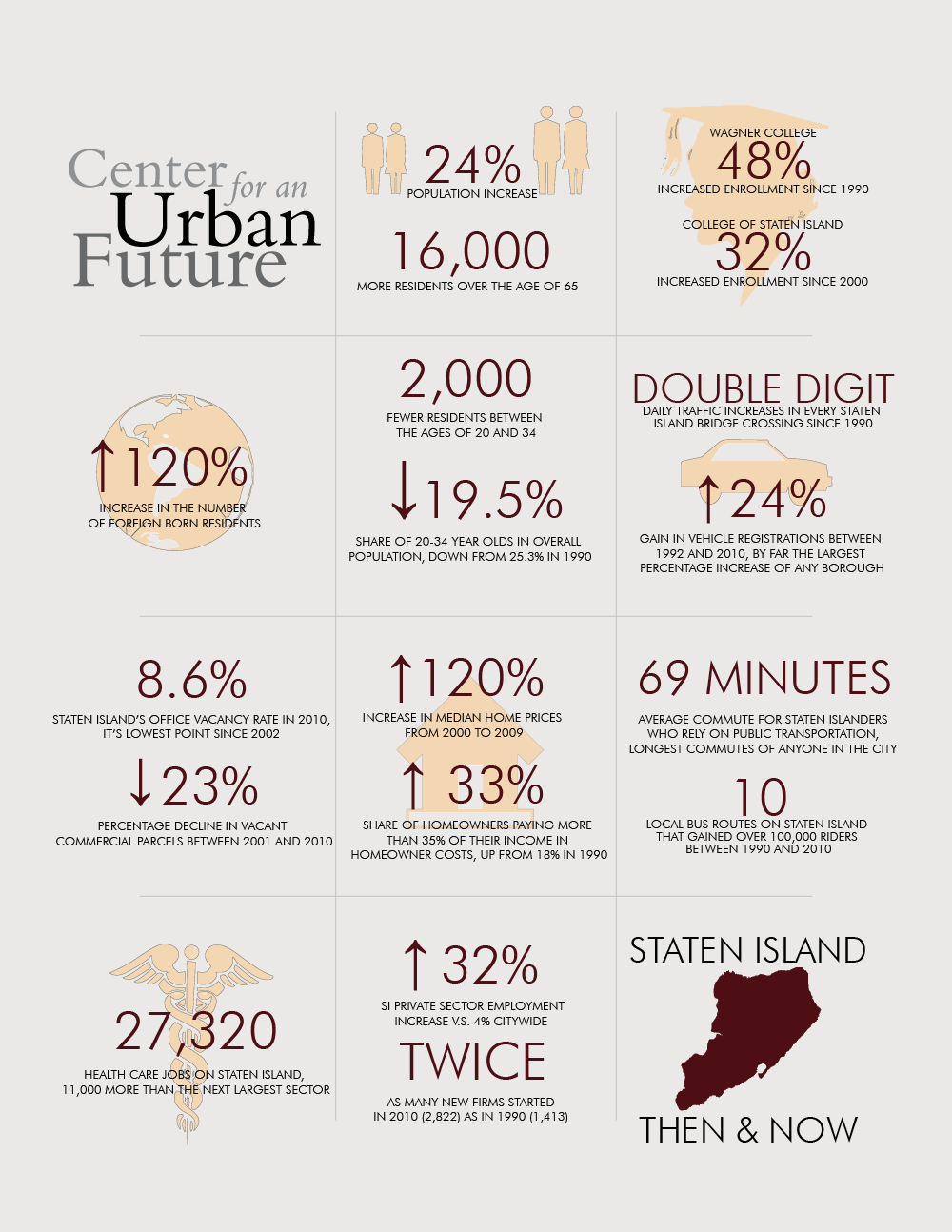

Any study of Staten Island’s changes over the past two decades must start with its 24 percent increase in population. This was significantly higher than the next fastest growing borough (the Bronx, with a 15 percent gain) and more than triple Manhattan’s growth rate.

While the population growth has been relatively evenly spread across the borough, Community District 3 on the island’s South Shore experienced both the largest numerical increase (41,745) and rate of growth (33 percent). Community District 1 on the North Shore, the only district to lose population between 1980 and 1990, had a 29 percent increase between1990 and 2010.

It is an older borough today, with 16,000 more residents over the age of 65 in 2010 than in 1990. It is also significantly more diverse. The share of white non-Hispanic residents has fallen from 80 percent in 1990 to 68 percent in 2010, while the share of residents who are Black, Hispanic and Asian has increased. These trends will likely continue. In 2010, only 52 percent of Staten Islanders under the age of 18 were white non-Hispanics, down from 73 percent in 1990. In addition, the share of foreign born residents jumped from 12 percent to 20 percent between 1990 and 2010.

The added population has supported a slew of new businesses and jobs. Private sector employment on Staten Island increased by 32 percent between 1990 and 2009, compared to a 4 percent gain citywide. The borough’s share of all private sector jobs in the city reached its highest level in 2009 (2.83 percent), up from 2.24 percent in 1990. There were twice as many new firms started in 2010 (2,822) as in 1990 (1,413) and the number of self-employed residents grew by 38 percent.

The fastest growing sector on Staten Island during the past decade was accommodation and food services, with a 35 percent increase in jobs, followed by educational services, which grew by 31 percent. A big part of the education growth is due to expansions at local colleges. Enrollment at Wagner College is up 48 percent since 1990. At the College of Staten Island (CSI), enrollment has risen by 32 percent just since 2000.

The health care sector added roughly 3,000 jobs in the past 10 years. It is far and away the borough’s job engine; with 27,320 jobs on Staten Island, health care has well over 11,000 jobs more than the next largest sector (retail trade, with 15,953 jobs).

Staten Island’s economic landscape has shifted in many ways. Between 1997 and 2007, there was a 121 percent growth in computer systems design services firms and an 86 percent jump in management consulting services companies. Other sectors with strong gains were home health care services (with a 58 percent increase in firms), architectural services (33 percent) and investigations and security services (29 percent). On the down side, there were 42 percent fewer travel agencies. In retail, there were big increases in electronics and appliance stores (70 percent), full service restaurants (44 percent) and supermarkets and other grocery stores (25 percent) but declines in sporting goods stores (down 50 percent), florists (-41 percent), gas stations (-34 percent) and hardware stores (-24 percent).

And though new development has all but ground to a halt—the number of building permits in 2009 (271 buildings) was actually lower than in 1990 (776 buildings)—the borough’s office vacancy rate in 2010 (8.6 percent) was at its lowest point since 2002 and the retail vacancy rate was a slim 2.9 percent, down from 4.5 percent in 2007. And while the 2010 industrial vacancy rate (5.3 percent) was higher than the level from the last five years, it is still about a third of what it was from 2000 to 2003.

Meanwhile, the number of vacant parcels on Staten Island shrunk between 2001 and 2010—commercial by 23 percent and residential by 17 percent.

Another good sign for the local economy is that Staten Islanders have become more highly skilled. While Staten Island currently has a lower share of residents with bachelor’s degrees than any borough except the Bronx, the number of Staten Islanders with at least a bachelor’s degree has almost doubled since 1990, from 50,953 to 91,031. Importantly, the percentage of Black or African American residents on Staten Island with at least a bachelor’s degree has increased from 14.5 percent in 1990 to 22.5 percent in 2009, while the share for Hispanics has gone from 13.6 percent to 16.2 percent.

Not all the changes over the past two decades were positive. Perhaps most noticeably, the explosive population growth led to significantly more vehicles and nightmarish traffic congestion.

Staten Island’s 24 percent gain in vehicle registrations between 1992 and 2010 was by far the largest percentage increase of any borough. Only one other borough (Manhattan, with an 11 percent gain) had a double-digit increase in vehicle registrations during this period, while both the Bronx (-10 percent) and Brooklyn (-8 percent) actually saw declines. Staten Island went from being the borough with the fewest registered vehicles in 1990 to having more than both the Bronx and Manhattan by 2010.

Every Staten Island bridge crossing has seen a double-digit increase in daily traffic since 1990, with traffic on the Bayonne Bridge growing by a staggering 64 percent. But while 54 percent of Staten Islanders drive to their jobs (up from 49 percent in 1990), 15,000 more residents took public transit to work in 2009 than in 1990.

The bus ridership increases underscore the need for transit investment. Between 1998 and 2010, 10 local bus routes on Staten Island gained over 100,000 riders. Express bus ridership was up by 55 percent.

Two local bus routes experienced a spike of more than a million riders between 1998 and 2010—the S53 and S79. Not surprisingly, both take riders from Staten Island to Brooklyn, where 30,380 Staten Islanders worked in 2008, up from 25,256 in 1990.

Average commuting times for Staten Islanders are up just eight percent since 1990, but are still higher than any other borough. The modest increase may be due to the fact that the number of Staten Islanders commuting to jobs in Manhattan has barely budged over the past two decades (up by 4 percent), while thousands more residents are staying in Staten Island for work. Between 1990 and 2008, the number of Staten Island residents who work in their own borough increased by 32 percent and those going to Brooklyn or New Jersey increased by 22 percent.

It takes Staten Island residents who drive to work 32.8 minutes, on average, to get to their jobs, which is actually a shorter trip than residents of Brooklyn and Manhattan who drive. It is Staten Islanders who rely on public transportation that have, by far, the longest commutes of anyone in the city (69 minutes vs 54 minutes for those in the Bronx, the borough with the next longest transit commute).

The population boom also unleashed a torrent of new housing development. Between 1990 and 2010, the number of housing units on Staten Island increased by 26 percent, a far larger increase than any other borough. Many Staten Islanders frown upon this burst of housing activity since it was not accompanied by adequate planning or infrastructure investment.

Despite all this, however, one of the greatest legacies of the past two decades on Staten Island—as well as in the other boroughs—has been a dramatic increase in housing prices, suggesting that the supply of housing has not kept pace with demand. After a relatively modest increase of 12 percent from 1990 to 2000, median home prices on Staten Island increased more than 120 percent from 2000 to 2009. The share of homeowners paying more than 35 percent of their income in homeowner costs increased from 18 percent in 1990 to 33 percent in 2009. Similarly, the percentage of Staten Islanders paying more than 35 percent of their income in rent increased from 30 percent in 1990 to 45 percent in 2009.

Staten Island has a proud history as a launching pad for first-time homeowners, but the rapidly rising housing costs may be making the borough considerably less attractive for young families and singles. Despite the huge overall population gains over the past two decades, the number of children under age 5 actually declined between 2000 and 2009 and the share of the borough’s population under age 5 dropped from 7.4 percent in 1990 to 6.7 percent in 2000 and 6.0 percent in 2009—a sign that fewer families are raising kids on Staten Island/

Similarly, there were roughly 2,000 fewer people between the ages of 20 and 34 in 2009 than in 1990. The share of 20-34 year olds in Staten Island’s overall population declined from 25.3 percent in 1990 to 20.4 percent in 2000 and 19.5 percent in 2009.

These are troubling trends, and they are undoubtedly connected to the sharply rising cost of housing and what many local residents view as a declining value for their money due to longer commutes, mounting traffic problems and insufficient transit options. The fact that the average construction cost per residential unit on Staten Island has risen from $66,203 in 1990 to $136,407 suggests that future housing development may lag what is needed and that prices may remain high.

The borough also must confront other challenges brought on by the recent recession. At 8.6 percent, the unemployment rate in January 2011 was almost double the rate from January 2008 (4.6 percent). For much of the past two decades Staten Island had the lowest unemployment rate among all five boroughs, but it is now only third lowest, behind Manhattan (7.7 percent) and Queens (8.5 percent). Things may get even worse if, as anticipated, many public sector jobs are axed as to deal with gaping budget gaps. Staten Island is particularly vulnerable since 22 percent of its residents have government jobs, a far higher percentage than any other borough (the Bronx is second, at 18 percent).

In addition, while small businesses have become increasingly critical to the borough’s success—the average private sector business on Staten Island has become significantly smaller over the past 10 years, with firm size dropping from 11.4 employees to 10.2 employees between 2000 and 2009—they are still having trouble accessing financing. In 2010, there were fewer loans guaranteed by the U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) on Staten Island than each of the last seven years.

What will the next 20 years bring for Staten Island?

Staten Island will almost certainly continue to add people, the elderly population is expected to increase dramatically and the health care sector will likely expand further. Beyond that, what happens in the next two decades—and whether the borough can address its current challenges and builds on its significant assets—will likely depend on whether local and city officials can plan better for what lies ahead.