Each new decade brings a fresh wave of concern that New York City risks losing some of its cultural spark. Even before the coronavirus pandemic hit, New York’s soaring cost of living and the lure of cities from Baltimore to Berlin had threatened the city’s position at the apex of global culture. At the same time, a powerful, growing force of cultural vibrancy has reenergized the city in recent years and sharpened New York’s creative edge: immigrant artists.

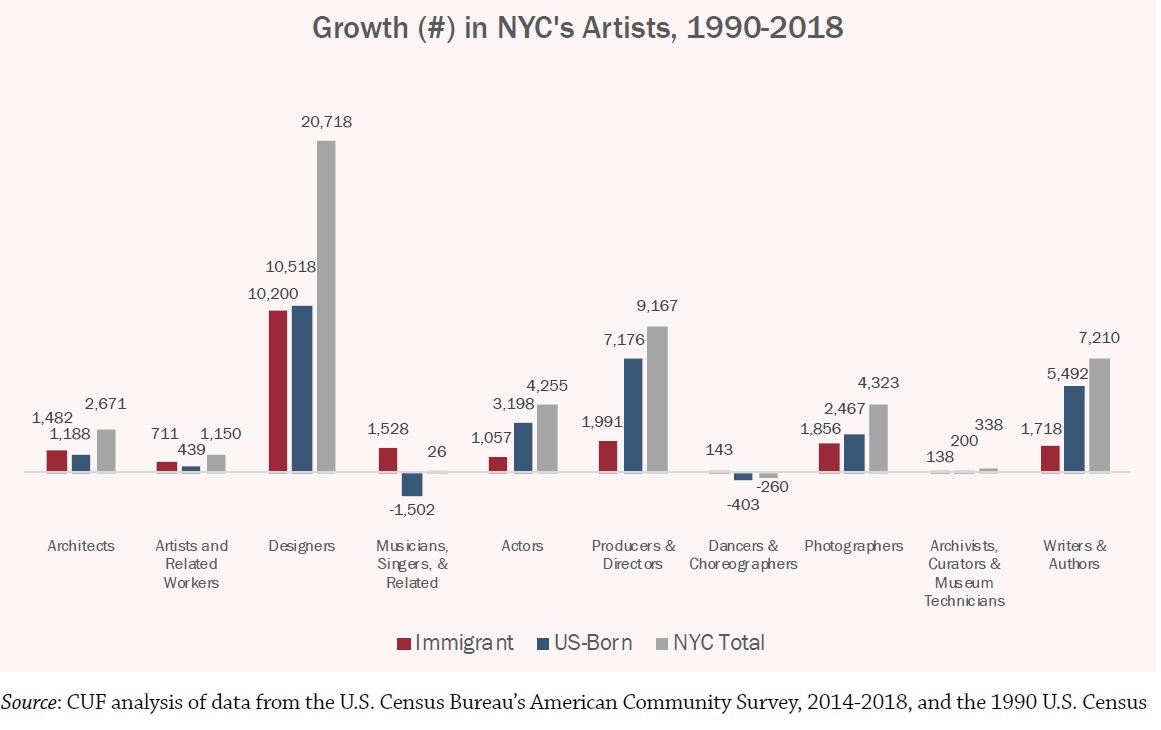

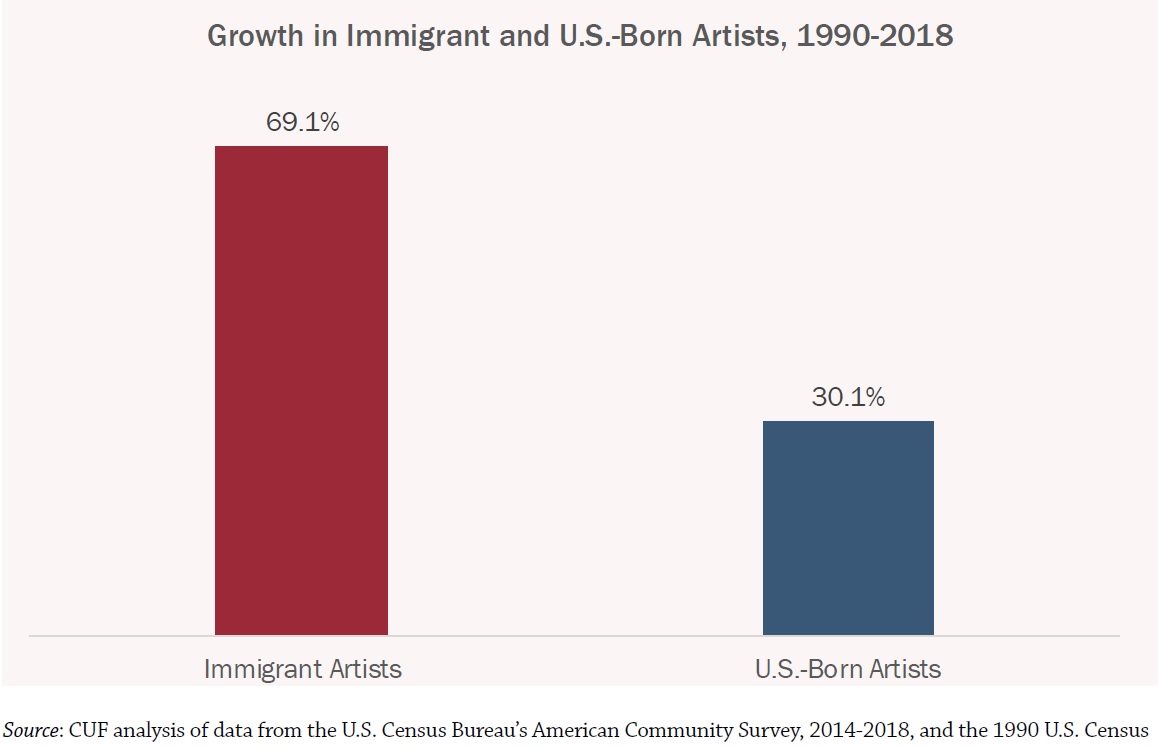

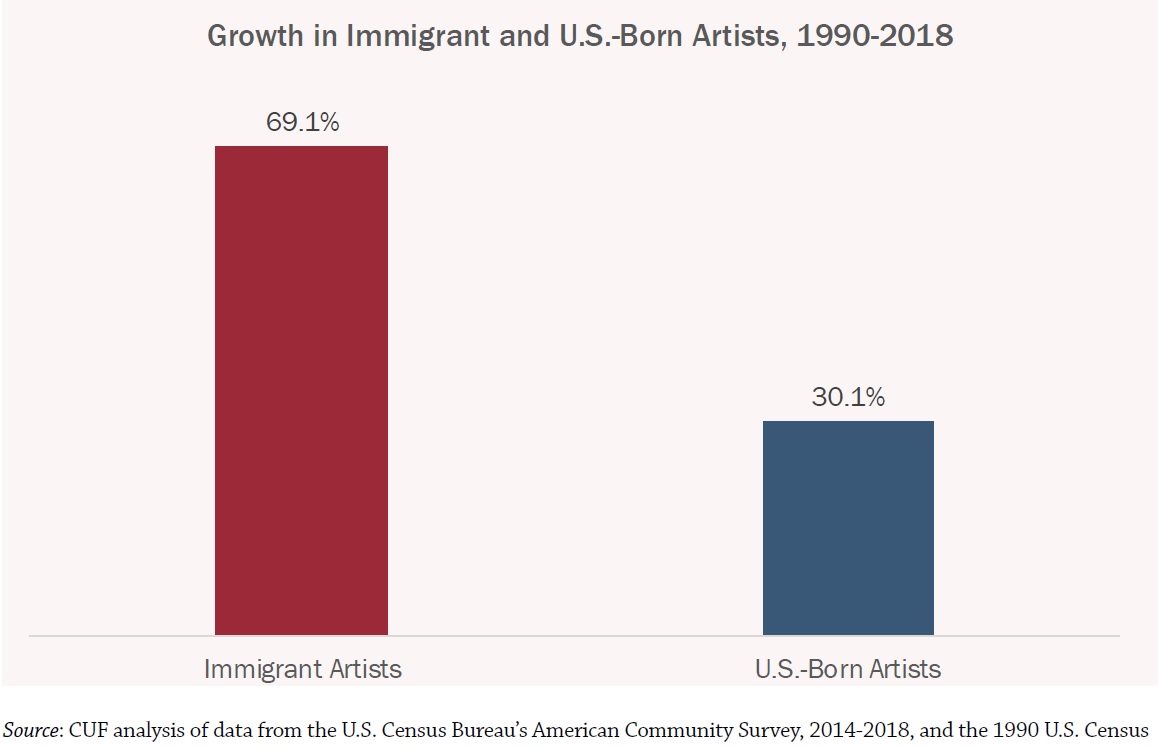

Foreign-born artists have long been here, birthing world-altering movements from abstract expressionism to hip-hop. More than any previous era, however, immigrants have become pivotal to the success of the arts in New York. The number of immigrant artists has grown 69 percent since 1990, compared to a 30 percent increase in U.S.-born artists. The ranks of immigrant producers and directors, writers, and photographers have all doubled since 1990, while the number of immigrant actors has grown by almost 150 percent. Today, the city is home to 12 percent of the nation’s immigrant artists, far more than any other U.S. city. Across multiple disciplines, immigrants burnish the city’s global reputation for artistic excellence, from the nine New York-based, foreign-born artists who were featured in last year’s Whitney Biennial to the five 2019 Bessie Award-winning immigrant dancers and choreographers, to hip-hop superstars like Trinidad-born, Queens-raised Nicki Minaj.1

But now the livelihoods of countless immigrant artists—and the survival of the cultural organizations that champion their work—are facing major threats. Without the benefit of endowments or large donor bases to help cushion the blow, many immigrant-led and immigrant-serving arts organizations are facing fiscal catastrophe, reporting revenue losses amounting to 50 percent or more of their annual budgets. These organizations were particularly vulnerable to financial shocks before the pandemic hit, with the average ethnic arts nonprofit bringing in just one-third the government funding and less than 7 percent of the board contributions received by mainstream peer organizations. Meanwhile, many immigrant artists have struggled to access government relief, even as income from exhibitions, performances, and side jobs has all dried up.

While city support for immigrant arts had increased in recent years, that funding is now in jeopardy: the city’s 2021 budget cuts more than $23 million from the Department of Cultural Affairs and slashes funding for Council discretionary initiatives by $79 million—funding that many immigrant-serving arts organizations rely on.

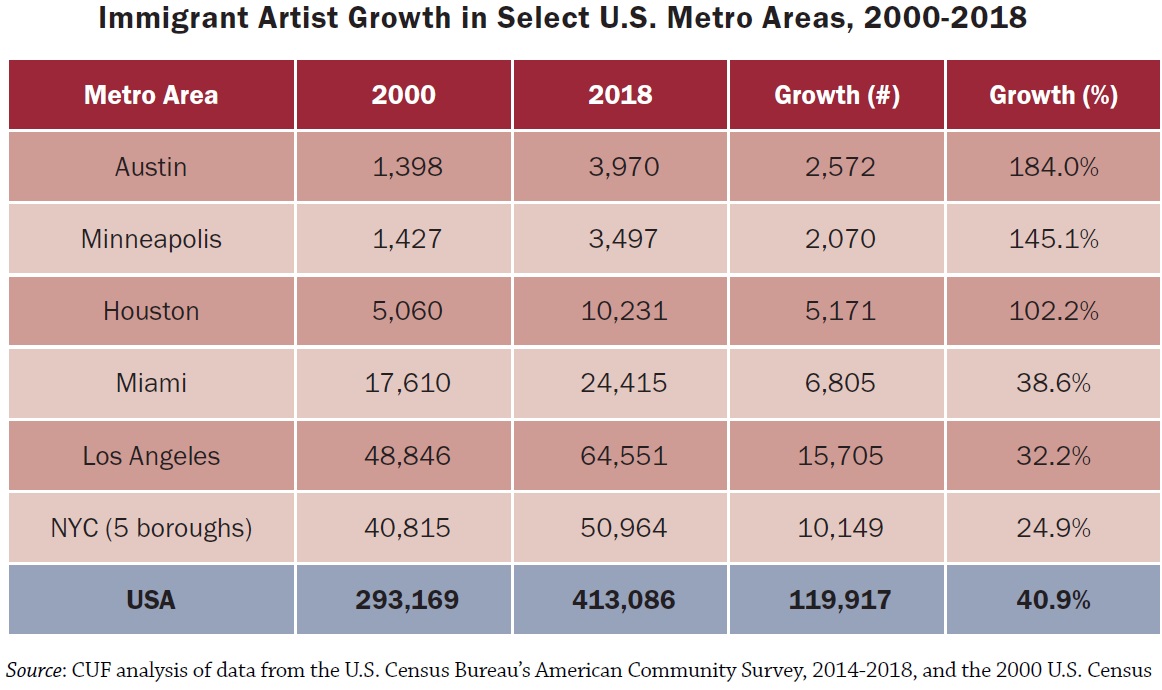

Absent a new level of support, New York risks losing its status as a beacon of cultural exchange and innovation, and jeopardizing its prospects in a daunting economic recovery. To continue attracting and sustaining brilliant creators from across the world—and keep pace with cities like Los Angeles, Houston, and Miami that are now experiencing far faster growth in their immigrant artist communities—city policymakers and cultural leaders will have to do far more to help immigrant artists and arts organizations to survive the current crisis and weave new strength into the cultural fabric of New York City.

This report provides a new level of detail on the landscape of immigrant arts in New York City— and what’s needed to sustain immigrant arts communities across the five boroughs. Funded by the New York Community Trust, the Laurie M. Tisch Illumination Fund, and Rockefeller Brothers Fund, the report builds on the Center for an Urban Future’s previous research about the vital role of the arts in New York’s economy, including the 2015 Creative New York study. The report documents the essential contributions of immigrant artists to New York City, identifies the core challenges facing immigrants in the arts both before and amid the current crisis, and advances more than a dozen specific recommendations to support immigrant artists and immigrant-serving arts organizations and strengthen the city’s creative future. It was informed by extensive data analysis and interviews with over 100 New Yorkers, including immigrant artists, directors of immigrant-led cultural and social service organizations, leaders of other cultural institutions, art critics, creative professionals, and government officials, among many others.

Since the coronavirus pandemic hit in March 2020, arts organizations of all kinds have experienced tremendous financial hardship. But our research finds that many of the city’s immigrant-serving arts organizations and working immigrant artists have taken the greatest hit. Galleries, performance venues, and community spaces that champion the work of immigrant creators have gone dark indefinitely, with few financial resources to cushion the blow.

New data from immigrant-serving arts organizations reveals the scale of the crisis. Flushing Town Hall, a multidisciplinary global arts venue in Queens, has lost more than $400,000 in earned income through June—over 17 percent of its annual budget—and projects losses up to $500,000 for the late summer and fall, including lost income from weddings, events, ticket sales, and government contracts. The Nuyorican Poets Cafe has been closed since March with zero earned revenue and projects losses of between $400,000 and $450,000 for the year—more than half of its annual budget. The Bronx Academy of Art and Dance has lost over $20,000 in revenue from canceled events and rentals since March, and has spent more than $40,000 on continued rent payments for its shuttered space.

For many immigrant artists, the impact of COVID-19 has been particularly devastating. Dancer and choreographer Hussein Smko saw the premiere of his autobiographical dance work postponed by several months, and he lost a potential $40,000 grant and had to cancel a fundraiser, both due to the pandemic. His future plans to tour in his native Kurdistan have also been placed on indefinite hold. Without live events, Colombia-born musician Johanna Casteñada has lost her main source of income and is surviving on unemployment and micro-grants. But in her band, Grupo Rebolu, “We’re nine musicians affected. And that’s only in my band.” Artists from New York’s Himalayan communities have lost income from canceled weddings and festivals, says community activist Nawang Gurung. But most of these artists actually make a living working under the table in particularly hard-hit industries like restaurants, nail salons, and childcare: “They don’t get unemployment because they were paid in cash,” says Gurung. “It’s been a challenge for seven months just to pay the rent, and groceries are not cheap in New York City.”

Immigrants have experienced the steepest financial losses of any New Yorkers, with more than half of all immigrant workers in many communities losing their primary source of income. The impact of this crisis is compounding the financial challenges already affecting immigrant artists, who earn just 88 cents on the dollar compared to U.S.-born artists. Given the challenge of earning a living from art alone, many worked in the city’s hardest-hit industries to support their artistic practices—from art handling and performance venues to restaurants and nightclubs—and a large share of these jobs have either disappeared or been dramatically scaled back. In addition, the deep economic pain afflicting immigrant communities, coupled with struggles accessing federal cash relief or unemployment insurance, has forced immigrants to cut back drastically on spending, resulting in patronage of artists and arts organizations all but disappearing in recent months.

Given the vital, growing role that immigrant artists play in cultivating the city’s broader creative ecosystem, these dislocations and disruptions pose a major threat to the city’s long-term economic health and cultural vibrancy.

“We Need to Survive” COVID-19 Threatens the Careers and Livelihoods of NYC’s Immigrant Artists

Sirène Dantor Saintil is the lead vocalist and founder of Fanmi Asotò, a Haitian song and drum group and cultural organization rooted in Vodou traditions. For Saintil and her husband, master drummer Jean Guy “Fanfan” Rene, Fanmi Asotò’s performances and workshops are the sole source of income for their family, and since COVID hit, they’ve had no work and no income. “My husband and I are both immigrants, both artists, this is the way we live our life, and now we’re stuck and don’t know what to do. Nobody calls us to perform. I usually have a contract for a year, and now everything has stopped,” says Saintil. “Right now to survive, to feed my family, I have to go to food banks.” Beyond a $500 emergency grant from the Brooklyn Arts Council and the occasional small donation for a free outdoor performance, Saintil has received no relief. “Make people understand us as immigrants, performers, artists,” she says. “We need to survive. This is our life.”

We interviewed a Lebanon-born multimedia artist who asked to be identified as “Sophia.” She currently lives in upper Manhattan with her partner, also an artist and immigrant, and two children. Her work has been exhibited at the Brooklyn Museum and Dumbo Arts Festival. As a result of the pandemic, both she and her partner have lost all of their income from their art practices and they have been unable to access any relief grants. “There is basically zero happening in terms of shows or speaking engagements or anything like that. It’s like our career has come to a standstill,” she says. “In terms of money in our pocket there is really absolutely nothing.” Sophia’s partner is unable to work his side job as an Uber driver to avoid exposing their family to the virus. Their family is now relying on her day job, which generates a fraction of their previous income.

Dancer and arts educator Aeilushi Mistry was born in Gujarat, India, and is now based in Bay Ridge. For the past eight years, she has led a traditional Arti, a Hindu lamp ceremony, on the shores of the East River in Brooklyn, connecting hundreds of New York families with the culture of India and receiving coverage in the New York Times. This year, her life’s work has ground to a halt. “My calendar is completely empty right now,” she says. “In a normal year, I’d have two or three residencies in schools in both spring and fall, teaching students about Indian culture through dance. I would lead movement workshops and seminars and give performances in the community several times a month. And I’d be performing at festivals. But those were all completely canceled or really scaled back.” Mistry estimates that she’s lost at least $15,000 to $20,000 in income from her work as an artist this year and is having doubts about her future in New York. “Artists are essential, but there’s no work for us,” she says. “It feels like one door after another is closing.”

Tijay Mohammed is a Ghana-born artist based in the Bronx who has organized community-based projects at the Brooklyn Museum and Studio Museum in Harlem. With a full calendar of exciting projects scheduled, Mohammed anticipated that 2020 would be his breakout year. As the pandemic intensified, however, he sustained one setback after another. He had been invited to teach workshops and organize projects at several institutions throughout the year, all of which were either canceled or scaled back to online-only programs. Mohammed estimates he lost about $12,000 in income due to cancellations alone. In addition, sales of his work have suffered. “I had one piece priced at $15,000 that was going to sell, but it didn’t because the buyer lost her grandmother to COVID and was struggling,” he says. “My community relies on me, but I was struggling myself.”

Colombia-born Lina Montoya is a muralist, teaching artist, and designer based on the North Shore of Staten Island since 2010. Since her first commission for the NYCDOT in 2014, her work has centered on public art that engages the community, celebrates Staten Island’s diversity, and creates a sense of belonging. But her work relies on public commissions and community participation, which have all but vanished. “Everything fell apart,” says Montoya. “All my projects with the DOE were canceled. The four pieces I was supposed to do in 2020 never happened. I haven’t been able to start any projects remotely or through distance learning.” With no source of income and public schools closed, Montoya left New York City to stay with family in Colombia in the spring. She recently returned to New York, where she is trying to rebuild her career and find work again.

Immigrants are driving the growth and success of New York’s arts sector.

New York City’s artistic relevance, from the 19th century through today, is greatly owed to the passion and creative vision of international newcomers. “Immigrant artists and their work have been foundational to the city’s cultural make-up,” says Michael Royce, executive director of the New York Foundation for the Arts, a nonprofit supporting artists and emerging artists and arts organizations in New York State and beyond.

Immigrants to New York like Roberto Matta from Chile and Arshile Gorky from Armenia paved the way for New York’s groundbreaking abstract expressionist movement led in part by other immigrants like Mark Rothko from Latvia and Willem de Kooning from the Netherlands. Lithuanian filmmakers Jonas and Adolfas Mekas became leading figures of the New American Cinema movement, while fellow Lithuanian George Maciunas created the experimental Fluxus movement, involving artists like Yoko Ono and Shigeko Kubota from Japan and Nam June Paik from Korea. A lifetime of work by the French immigrant Louise Bourgeois influenced the development of feminist-inspired body art and installation art.2

Immigrant Caribbean musicians are arguably responsible for the birth of hip-hop—people like Bronxite hip-hop founders DJ Kool Herc from Jamaica and Grandmaster Flash from Barbados. Puerto Rican migrants have also made immeasurable contributions to the sounds and flavors of the city, with theater companies like Pregones/Puerto Rican Traveling Theater leading the nation in bilingual theater, and Boricua musicians like Tito Rodriguez and Tito Puente popularizing Cuban styles like mambo, giving rise to the distinctly New York sound that became known as “salsa.”3

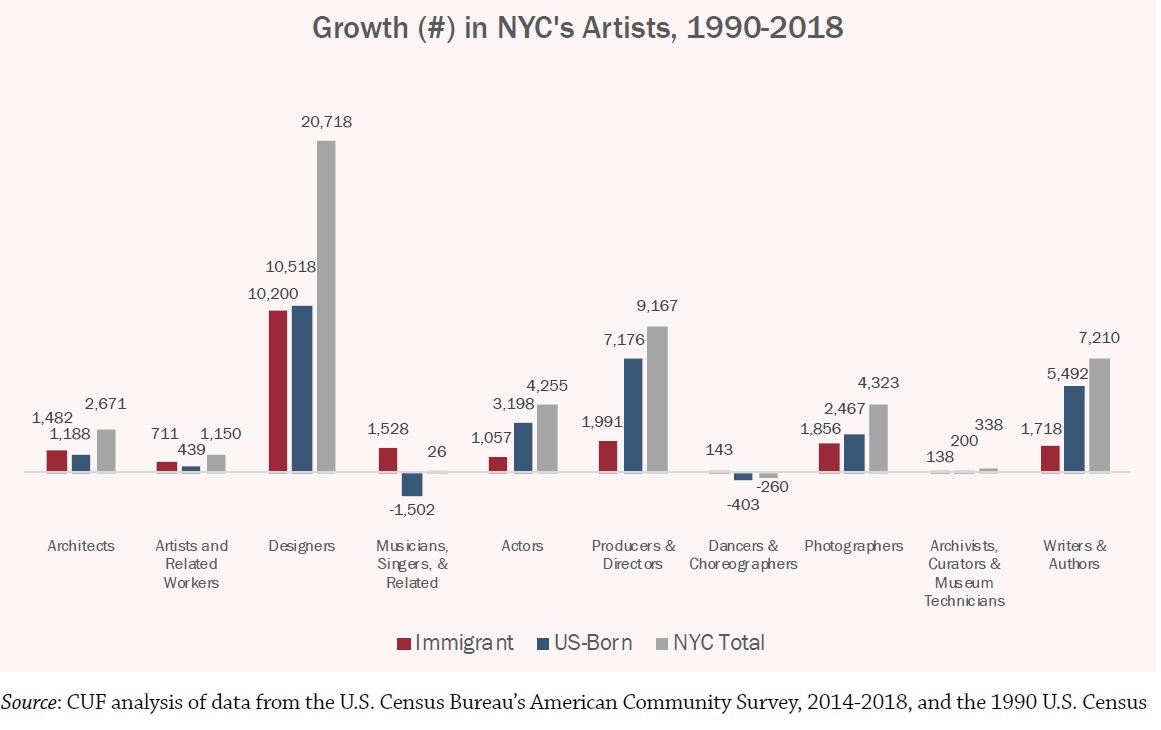

But while immigrants have always made vital contributions to the arts community in New York, immigrants now comprise a growing share of the city’s artists—and, our research shows, play a lead role in pushing technical and creative boundaries, preserving cultural heritage, and anchoring New York’s position as a global leader in contemporary culture. CUF’s analysis of Census data finds that New York City is now home to 50,964 immigrant professional artists, a 69 percent increase from just 30,139 in 1990. The share of New York City-based artists who are immigrants has also grown—from 24 percent in 1990 to 29 percent today. What’s more, the share of immigrants who are artists has grown by more than 25 percent. Since 1990, the number of immigrant artists grew faster than U.S.- born artists in every occupation we examined.4

Growth in immigrant artists can be seen across every artistic occupation since 1990, with the largest increase among designers, up from 12,068 immigrant designers in 1990 to 22,268 by 2018, a gain of 10,200. Fashion design in particular has been driven by immigrant contributions: a recent survey of fashion industry employers found that 85 percent said international talent was important to the growth and success of their business and 67 percent employed international talent.5

In some cases, immigrants are driving the growth even while the number of U.S.-born artists has declined: since 1990, the city recorded a net loss of 1,502 U.S.-born musicians and gained 1,528 immigrant musicians. This is no surprise to Bronx musician and co-artistic director of the Bronx Music Heritage Center Bobby Sanabria, who teaches music at New York University (NYU) and the New School. “Every semester,” Sanabria says, “I sign these recommendation letters for people applying for their 0-1B visas”— visas for extraordinary ability in the arts—explaining that many of his students hail from the Caribbean, Central and South America, China, Russia, Israel, and other parts of the world. “That’s why immigration is so important—because it reinvigorates culture, it reinvigorates all of the arts.”

But there are many more skilled immigrant artists who are not reflected in these statistics, such as those who practice in community settings. “We’ve got some of the world’s best artists here driving cabs in Brooklyn and digging graves in Queens,” says Peter Rushefsky, executive director of the Center for Traditional Music and Dance (CTMD). In fact, the tremendous growth in foreign-born, professional artists captures just a fraction of the enormous world of immigrant arts in New York City—from the steel-pan bands on Eastern Parkway every Labor Day to the nail salon worker who performs Chinese opera at night.

Immigrants are increasingly essential to the city’s global leadership in arts and culture.

Though many foreign-born artists do still operate on the margins of New York’s art world, more than ever before immigrant artists are being recognized for their excellence. Of the 78 artists and collectives shown in last year’s Whitney Biennial, 24 originate from outside the fifty states. Of those 24, nine live at least partly in New York City, including Wangechi Mutu from Kenya, Olga Balema from Ukraine, Meriem Bennani from Morocco, and others. “We’d be lost without the immigrant artists in New York,” says Andrew Russeth, art critic and former executive editor of ARTnews.6

Immigrants are also having a profound impact on the city’s music scene. “If you want to have a global presence you likely have to come to the U.S. and more specifically, New York,” says Justin Kalifowitz, CEO of Downtown Music Holdings. “If immigration is prevented, you lose that edge. New York City is home to some of the most culturally relevant musicians. Contemporary artists like Nicki Minaj who was born in Trinidad and raised in Queens are pushing the boundaries of popular music.”

From playwrights like Romania-born Saviana Stanescu, Poland-born Martyna Majok, and Korea-born Hansol Jung, to companies like Ma-Yi Theater Company and the Pan-Asian Repertory Theatre, immigrant artists and immigrant-serving groups are energizing the theater scene. Immigrants are also crucial participants in the New York dance world. Of the 13 dancers who received Bessie Awards in 2019, five were immigrants: nora chipaumire of Zimbabwe, Tania El Khoury of Lebanon, Shamar Watt of Jamaica, Alice Sheppard of Britain and Daina Ashbee of Canada.7

Immigrant artists are reshaping the film world in New York City. Of the 24 feature film directors presented by MoMA’s 2019 New Directors/New Films festival, which highlights emerging filmmakers from throughout the globe, twenty-one were born outside the United States, among which at least two are based in New York: Alejandro Landes and Lucio Castro. Of the 16 film directors who won Tribeca Film Festival awards in 2019, the majority were from other countries, including Brooklyn-based Rania Attieh.8

According to Barbara Schock, chair of NYU Tisch’s graduate film program, the program’s international diversity is crucial to its success. “There are two things that [immigrants] bring: they bring stories from other places and other ways of understanding the world, but they’re also bringing their new existence as an immigrant to our culture,” says Schock, “and it’s this duality that is incredibly vitalizing.” Schock points to the Taiwanese graduate Ang Lee and his film The Ice Storm, set in a quintessential American suburb, as well as the China-born graduate Chloé Zhao and her film The Rider, set in South Dakota.

Meanwhile, immigrant designers have perhaps the most substantial presence of immigrants in any arts sector. Of CultureTrip’s ten NYC-based fashion designers to know about in 2018, half were born outside the country: Canadian Chris Gelinas, Norwegian Eleen Halvorsen, Belgian Tim Coppens, and Australians Ryan Lobo and Ramon Martin. “I can’t imagine our industry or any of the arts industries in America existing without the rich cultural heritage [brought by] everybody that comes to the U.S.,” says Sara Kozlowski, director of education and professional development at the Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA).9

New York City–based immigrant artists are also among the nation’s literary giants, including Korea-born, Queens-raised Min Jin Lee, author of the acclaimed novels Pachinko and Free Food for Millionaires; Mexico-born, 2019 MacArthur “Genius” grant award-winner Valeria Luiselli, author of The Story of My Teeth and Lost Children Archive; and Peru-born Daniel Alarcón, author of Lost City Radio and At Night We Walk in Circles. That’s not even counting Salman Rushdie, a New Yorker since 2000.

The impact of New York’s immigrant artists extends far beyond accolades and awards. Immigrants are pioneering innovative, interdisciplinary practices. In both the 2018 and 2019 cohorts at NEW INC, the New Museum’s cultural incubator for artists, designers, technologists, and creative entrepreneurs, over 40 percent were immigrants. And by melding genres and cultural traditions, immigrant artists collaborate to develop completely new styles. “All of these art forms need rejuvenation,” says David Johnston, executive director of Exploring the Metropolis (EtM), a nonprofit that supported access to workspace for performing artists for almost 40 years, before circumstances tied to the pandemic forced the organization to cease operations in June. “They all need these shots of something new, and a new story and a new perspective.”10

More than ever, that rejuvenation comes through the contributions of immigrant artists, many of whom are anchors in their communities, sharing traditions, mentoring the next generation, and performing in community settings. When they are not touring internationally or performing at premier venues like Lincoln Center, immigrant artists and groups like the New York Crimean Tatar Ensemble of Borough Park and the Queens-based Mariachi Real de Mexico lead arts and cultural organizations dedicated to supporting and serving immigrant artists and audiences.

Students learn guitar at the Mariachi Academy of New York. Photo courtesy of Ramon Ponce.

Immigrant arts organizations sustain and uplift the city’s most vulnerable communities.

New York City’s immigrant arts organizations greatly enrich the communities they serve, preserving traditions and bringing different generations together to celebrate shared culture. In a time of crisis, these artists form a supportive ecosystem that sustains New York’s immigrant communities through even the darkest times. In this report, we use the term “immigrant arts organizations” to encompass a diverse mix of arts and cultural organizations that are led by immigrants, serve immigrant populations, focus on specific ethnic and cultural arts practices and expressions, and/ or support and interact with immigrant artists and audiences in other ways.

Immigrant arts organizations create safe spaces for undocumented families, single-parent youth or youth whose parents work around the clock, monolingual new arrivals, and people needing space to process and heal from traumas like war, displacement—and the COVID crisis. Executive director of Calpulli Mexican Dance Company Juan Castaño describes the atmosphere of trust in the company’s community classes: “We’ve had families come to us and say, no matter what’s happening, whether it’s at our job or in the news or in school, we always know that we can come here.”

Immigrant arts organizations and their leaders are also crucial facilitators of civic engagement. Founder and Executive Director of Napela, Inc. Adama Fassah invites immigration lawyers and other informative visitors to her cultural festival in Staten Island. Shelley Worrell, founder and chief curator of CaribBEING, a Brooklyn-based organization that promotes Caribbean culture, served as Head of Caribbean Partnerships at the U.S. Census to help increase the Caribbean community’s awareness and participation in the 2020 census.11

And art can be a powerful means for immigrants to express political demands. New Sanctuary Coalition often employs art as a tool of protest: in 2017, activists carried blocks of melting ice to a detention center to protest against U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. The following year, the coalition and other groups organized a march in which attendees were each asked to bring a 25-pound suitcase in imitation of the small suitcases that families are allowed to provide to relatives facing deportation.12

Undocumented, temporary worker, and persecuted artists face major barriers.

For New York’s many undocumented artists, simply living in the city and practicing their art form is politically charged: Due to legal status, they arguably face the greatest difficulty in learning and pursuing their craft.

Undocumented New Yorkers are ineligible for federal tuition grants, face barriers to employment, and are often ruled ineligible for residencies and fellowship requiring work authorization. “There are a lot of undocumented artists who are doing really great work, and important work, that we would have loved to be able to support,” says Suzy Delvalle, former executive director of and current advisor to Creative Capital, a nonprofit that supports innovative and adventurous artists nationwide. “Understanding how we could get to that point would be really helpful.”

Radical changes to federal immigration policy and enforcement are also having harmful ramifications for New York’s international students, artists on temporary worker visas, and persecuted artists seeking to resettle here. According to interviews with students and faculty at New York’s art schools and MFA programs, in recent years many graduating international art students who might have settled in New York have been returning to their home countries or seeking out other global arts hubs. “In the past few months within my close community, everyone’s leaving,” says Yasi Alipour, an Iranian artist and graduate of Columbia University’s MFA program in visual arts, who was interviewed shortly before the pandemic hit New York. New York-based arts groups that collaborative with foreign groups are also finding it more difficult to secure visas for their partners.13

“That puts us in a very perilous position as a nation,” says Tina Kukielski, executive director and chief curator of Art21, a nonprofit presenter of contemporary art. “To not be seeking out individuals who have exceptional talent, that have something unique they can offer to the cultural landscape of New York City.”

Immigrant-serving arts organizations have been hit especially hard by the coronavirus pandemic

The coronavirus pandemic and ensuing economic crisis has hit immigrant artists and immigrant-serving organizations especially hard. Many artists have lost all income from performances and exhibitions, and others are facing months without supplemental income from work in restaurants, bars, museums, galleries, and performance venues. For immigrant-run and -serving arts organizations that were already financially vulnerable before the pandemic, the loss of earned revenue is proving devastating, and there is little sign of relief.

Flushing Town Hall has lost more than $400,000 in earned income through June—over 17 percent of its annual budget. With a $2.3 million budget, the organization projects up to $500,000 in additional losses for the late summer and fall, and no endowment to cushion the blow.

Nuyorican Poets Cafe has been closed since March and estimates a loss of more than $400,000 compared to last year—more than half of its annual revenue.

More than 40 percent of the $220,000 budget for the nonprofit Bangladesh Institute of Performing Arts comes from revenue raised from its classes teaching Bangla music and dance, which are canceled for the foreseeable future.

Centro Cultural Barco de Papel in Jackson Heights, a Spanish-language bookstore and arts venue, is facing the prospect of closing for good, as the space’s majority-immigrant patrons have been deeply affected by the crisis. “We are surviving based on the immigrant population, who are the ones that are being hit the most,” says Paula Ortiz, the organization’s executive director.

The livelihoods of immigrant artists are threatened by rising rents and income disparities.

While the pandemic is worsening economic disparities between immigrant and non-immigrant New Yorkers, even prior to the crisis. Foreign-born New Yorkers made a median of nearly $15,000 less than U.S.-born New Yorkers—the undocumented, almost $23,000 less—which means that for many immigrant creatives, the daily struggle to survive leaves reduced time for artistic pursuits. Likewise, professional immigrant artists are out-earned by their U.S. born counterparts: from 2000 to 2018, foreign-born professional artists in New York made an average income of about $41,000 annually, less than the $46,600 annual income of U.S.- born artists.14

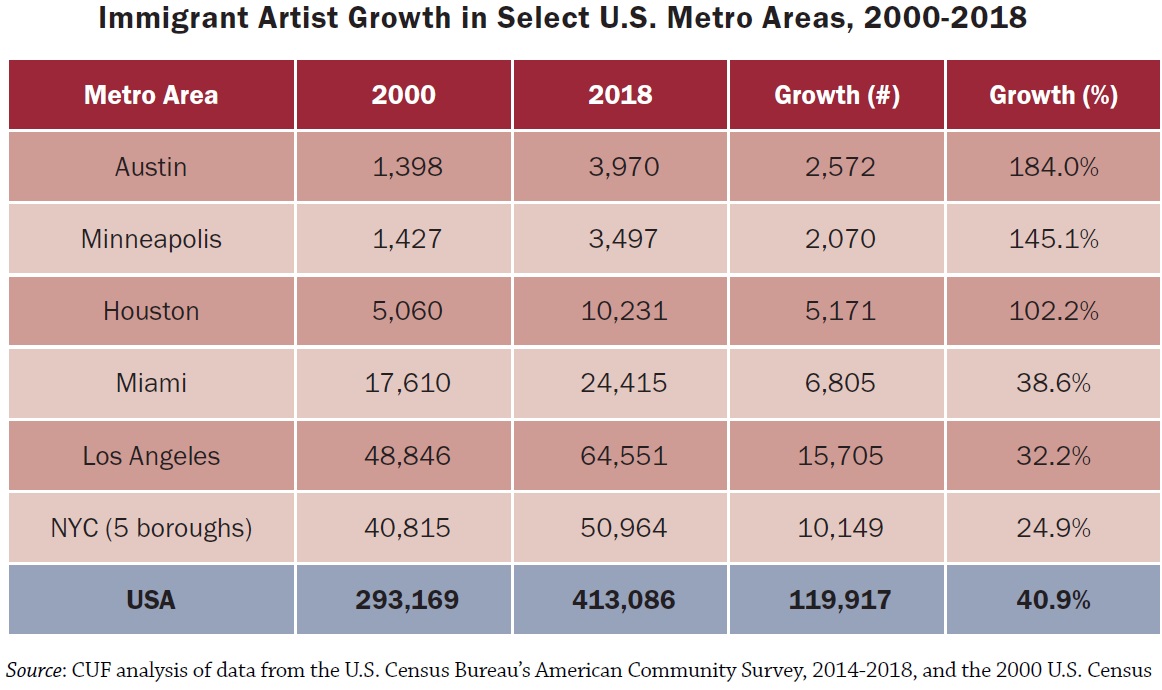

Lower incomes and rising living costs may be hampering the ability of the city’s immigrant artist population to grow to its full potential. While the number of professional immigrant artists grew by 35 percent, over 10,676 artists, from 1990 to 2000, growth in the 18 years since 2000 has been more modest, increasing by fewer total artists (10,149), an uptick of 25 percent. Meanwhile, the number of U.S.-born professional artists grew by less than 2 percent from 1990 to 2000, and then shot up by 28 percent from 2000 to 2018.

These economic conditions have made it so that other cities may now be better poised than New York to attract immigrant artists. While New York City still has the lion’s share of the nation’s immigrant artists, this share has declined. In 1990, New York City was home to 11 percent of the nation’s immigrants and 14 percent of the nation’s immigrant artists, while today the city is home to 7 percent of the nation’s immigrants and 12 percent of its immigrant artists. Over the past two decades, Los Angeles added more immigrant artists than New York, and cities from Austin and Houston to Minneapolis and Miami all saw their immigrant artist populations grow faster than New York’s. “It’s critical that if we want to maintain that New York City that we all know and love, that we sustain immigrant artists,” says Annetta Seecharran, executive director of Chhaya Community Development Corporation, a nonprofit focused on the economic well-being of South Asian and Indo-Caribbean New Yorkers.

Immigrant artists often struggle to get attention, and to get paid fairly when they do.

For the immigrant artists who call New York home, garnering attention from audiences, media, and funders is a challenge. This is especially true for immigrants who arrive here with limited economic means or under challenging circumstances. “Some artists are able to immigrate to the U.S. via a degree program in the arts, developing connections as well as experience with institutions and advancement in the sector,” says Sami Abu Shumays, deputy director of Flushing Town Hall. “Unfortunately, many others immigrate without any formal connections to the cultural sector, and often find themselves lost, having no idea how to market themselves or even to find arts organizations that might be interested in presenting their work.” Black and Latinx immigrants remain seriously underrepresented in the arts, making up only 26 percent of the city’s immigrant professional artist population, though they make up 53 percent of the city’s immigrant population.

Even immigrants who obtain support from a local institution or cultural organization might still struggle to gain mainstream recognition, especially if they live and work far outside Manhattan, or their work doesn’t conform to western notions of what constitutes art. “It’s a constant uphill battle,” says Catherine Peila, director of programs and artist services at the Jamaica Center for Arts and Learning. “How to get the audience in, how to have the audience to pay for it, how to get funders to support it as a professional art form where the artist is respected and paid the appropriate amount of funding.”

When they do have an opportunity to perform, immigrant artists often find themselves underpaid, or not paid at all. “No one would think of paying a cellist at Lincoln Center those low fees or expect something for free, yet some institutions would offer that to a percussionist from the Bronx,” says Elena Martinez, City Lore folklorist and co-artistic director of the Bronx Music Heritage Center. A 2019 study by Dance/NYC found that 22 percent of the immigrant dance workforce surveyed do not receive any form of income through dance-related activities.15

Immigrant-serving arts organizations struggle to find and keep affordable space.

Like individual artists, immigrant-serving arts organizations also strain to cope with economic realities. The city’s soaring rents have caused groups to lose original spaces and made it only harder to maintain makeshift, temporary solutions. Even prior to the pandemic, organizations like Local Project, Centro Corona, and Bronx Academy of Arts and Dance (BAAD!) had each been displaced from a prior location. Some hubs for art and culture had shut their doors completely, including Librería Lectorum and Librería Macondo in Manhattan, and Century Dance Complex in Staten Island.16

Immigrant-serving arts organizations are particularly vulnerable to rising rents because they possess fewer assets. Of the 27 small cultural organizations led by or working with immigrant communities that we interviewed, only one owned its own space. Furthermore, our review of 557 New York City arts organization profiles in the DataArts database from 2016 to 2019 found that organizations not serving a particular ethnic group possessed an average of $10.5 million in fixed assets, while organizations affiliated with a particular ethnic group possessed only $1.4 million in fixed assets.17

Some groups have found resourceful ways to adapt to a shortage of affordable rehearsal space— renting school gymnasiums, practicing in parks, or using the back rooms of restaurants during off-nights. Yet these adaptations constrain the ability of immigrant-focused arts organizations to build capacity, increase their impact, and create lasting connections with the communities they serve. “If the school closes, then of course we can’t rehearse,” says Luz Soliz, founder of Wabafu Garifuna Dance Theater Company, whose group preserves Garifuna culture through dancing, singing, and drumming, on rehearsing in a school building. “Naturally, we don’t have a key. And there’s not enough space to leave our costumes and drums on site.”

Immigrant-serving arts organizations face unique challenges raising revenue and accessing philanthropy, which in turn limits growth.

As with other arts organizations, immigrant-focused groups need revenue to survive, but because they often are dedicated to serving lower-income communities, raising money—whether from audience attendance or from wealthy donors—can be a challenge, leading to major disparities in revenue. Our research found that on average, non-ethnic arts organizations in the city bring in $4.8 million in total revenue, compared with only $891,000 for ethnic groups, according to a review of over 1,300 DataArts profiles.

With a lack of connection to wealthy donors, fundraising is a particular challenge, which can be exacerbated by preexisting neighborhood inequalities. According to our analysis of the DataArts profiles, non-ethnic cultural organizations obtain about 14 times the average earned revenue of ethnic organizations, along with about six times the average corporate revenue, and 15 times the revenue from trustees.

Immigrant-serving arts organization can get trapped in a vicious cycle, where a lack of mainstream attention precipitates a lack of funding, which in turn means an organization is unable to build capacity and garner the recognition it might deserve. With smaller budgets and fewer staff than other cultural organizations, those who work or volunteer for immigrant-serving arts organizations often juggle many responsibilities. “The team works together to do the grant writing, but it’s also the same team that produces the event, sometimes the same team that’s performing,” says Juan Aguirre, executive director of Mano a Mano: Mexican Culture Without Borders. Of the 27 immigrant-serving organizations with budgets of less than $1 million (or not available) that we interviewed in-depth, seven did not have 501(c)(3) status, and of the 20 that did, only four had a salaried staff member dedicated to development.

Immigrant artists and immigrant-serving arts organizations depend on public funding, and yet receive far less than mainstream counterparts.

Immigrant-serving arts organizations and immigrant artists disproportionately depend on government funding, despite receiving far less support. Non-ethnic organizations profiled by DataArts receive an average of about $438,000 of their revenue from government sources (about 9 percent of their total revenue), while ethnic organizations receive an average of $148,000 of their revenue from government sources (about 17 percent of their total revenue).

But federal funding for arts and culture has waned in the 21st century. The National Endowment for the Arts received just $162 million in the 2020 budget, down from $176 million in 1992 (well over $321 million when adjusted for inflation).18

Given declining federal support, the New York State Council on the Arts (NYSCA) and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs (DCLA) play an increasingly important role in supporting the arts. But programs that support immigrant artists often make up mere fractions of the budget. For example, NYSCA’s lauded Folk Arts program constituted 2 percent of NYSCA’s total grant allocation to the five boroughs in 2019. And major geographic disparities exist in overall spending: NYSCA allocates $13 per capita in Manhattan, compared with less than $1 in the Bronx, Queens, and Staten Island, though some Manhattan-based organizations serve all five boroughs.19

Similarly, despite significant efforts by the de Blasio administration to reach smaller organizations in low-income communities, most city grant-making dollars continue to be spent on mainstream and Manhattan-based organizations. Of the DCLA grant dollars listed in NYC Open Data for FY 2018 (not including City Council discretionary initiatives), 62 percent went to Manhattan and 19 percent to Brooklyn, leaving 8 percent for the Bronx, 9 percent for Queens and 2 percent for Staten Island. Strikingly, while per capita DCLA grant funding citywide is about $4.79, and an outsize $15.37 in Manhattan, per capita spending in the ten neighborhoods with the highest immigrant populations was just $0.74. Our review of DCLA grantees listed in Open Data found that just 14 percent of the organizations funded indicated in their DataArts profile that they served a specific ethnic group.20

DCLA’s requirement that arts groups hold nonprofit status often poses an additional barrier to funding. Thankfully, individual artists and collectives without 501(c)(3) status can apply for funding from NYSCA through fiscal sponsorship, and from the city’s five borough councils. However, funding levels are not equal among the five councils: while about twice as many immigrants live in Queens than in Manhattan, the FY 2018 budget of the Queens Council on the Arts was just 40 percent the size of the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council’s.21

To their credit, the de Blasio administration and City Council have made substantial new investments in the arts in recent years—and directed some new support to immigrant artists and arts organizations. Since 2014, Mayor de Blasio and the City Council had increased DCLA’s operating budget from $157 million in FY 2014 to a record high of $212 million in FY 2020. Likewise, the City Council has increased support in recent years for immigrant artists and organizations, including funding the Cultural Immigrant Initiative (CII). Just last year, the New York City Economic Development Corporation and DCLA announced plans to build a performing arts center focused on the immigrant experience in Inwood. DCLA has also convened city policymakers, community-based organizations, artists, and other stakeholders to develop the CreateNYC cultural plan, which provides a roadmap to make the arts and culture sector more inclusive. From FY 2018 through FY 2020, DCLA committed an additional $8.2 million to cultural organizations that support low-income neighborhoods and underserved communities, and has invested over $1.2 million in a new language access fund.22

But the current economic crisis is jeopardizing that progress. The FY 2021 budget slashes funding for DCLA by $23 million—with the bulk of those cuts aimed at cultural programs funding, on which many smaller, immigrant-focused arts organizations rely. Additionally, major reductions in councilmembers’ discretionary budgets—enacted in response to the city’s bleak fiscal state—will have a serious impact on funding for smaller, community-focused arts groups, including $9 million in cuts to the Cultural Development Fund, and a $1 million cut to the CII program.23

Despite the progress made in recent years, including increased funding for immigrant-serving cultural organizations and the launch of several new programs, many of the challenges facing immigrant arts have gone largely unaddressed. As a result, New York risks losing the cultural diversity and creative spirit that make it a global icon—and cement the city as a beacon for the world’s most innovative and exceptional artists. To ensure New York City’s immigrant artists and immigrant-serving arts organizations are able not only to survive but to thrive, city leaders will have to redouble support for immigrant creative communities across all five boroughs—and the responsibility cannot fall to DCLA and NYSCA alone.

To strengthen these vital communities, city leaders will have to do much more to provide immediate relief from the ongoing pandemic, address the persistent affordability crisis, rectify the damage of the Trump administration, and help artists and organizations to overcome the many obstacles they face in earning revenue, handling bureaucracy, obtaining institutional funding, and navigating the immigration system. Even at a time of drastic fiscal constraints, the city can get creative in supporting immigrant artists— by launching new initiatives to connect immigrant artists with vacant storefront and commercial spaces, opening public spaces for immigrant arts performances and exhibitions, building space for immigrant arts into future neighborhood development plans, helping New York’s immigrant creative entrepreneurs to grow, and strengthening the reach and effectiveness of the borough arts councils. Together, policymakers, cultural leaders, government officials, and philanthropists can uplift and sustain the immense contributions of its immigrant artists and ensure that New York City maintains its position as a global hub of creativity.

NYC’s Immigrant Artists Step Up to Support Communities in Crisis

Across all five boroughs, New York City’s immigrant artists are using their work and platforms to support immigrant communities in crisis.

In early 2020, Filipino-American artists Jaclyn Reyes and Xenia Diente launched Bayanihan Arts in Little Manilla, Queens. Intended as a series of public art activations celebrating the Filipino diaspora, the project took on new meaning during the pandemic. “When COVID hit, we adjusted our project to create a mutual aid network between Little Manilla businesses and healthcare workers, many of whom are Filipino immigrants,” says Reyes. The project has worked with local restaurants to provide free meals to frontline workers, and collaborated with local artists to paint the neighborhood’s first mural dedicated to the Filipino community.

Ecuador-born, Bronx-based artist Francisco Donoso launched an “immigrant-powered shop” in August, with a goal of leveraging his burgeoning career to generate financial support for immigrants who are struggling during the pandemic. He has partnered with organizations that provide direct cash assistance to undocumented New Yorkers and advocate for immigrants and refugees, contributing up to 30 percent of the proceeds from his sales. He also employs “two younger, at-risk, undocumented artists that I can pay and mentor.”

Mexico-born arts advocate and curator Eva Mayhabal Davis sees immigrant artists using their creativity and problem-solving skills to help the communities hardest hit by the pandemic. “Some of the most successful mutual aid networks serving communities of color and immigrant communities are being led by artists,” says Davis. “People like Guadalupe Maravilla, who works with Bay Ridge Mutual Aid; the Indigenous Kinship Collective; and the creatives who work with Bed-Stuy Strong and Bushwick Mutual Aid. I’m proud to say that I’ve seen a lot of artists working in mutual aid networks, whether it’s setting them up or helping to promote them.”

Notes

1. Center for an Urban Future analysis of data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, 2014–2018 5-year sample and the 1990 U.S. Census. See methodology for additional information.

2. Artnet, “Roberto Matta.” Artnet, “What You Need to Know about Arshile Gorky, the Last Surrealist and the First Abstract Expressionist.” The Art Story, “Abstract Expressionism.” Bruce Weber, “Jonas Mekas, ‘Godfather’ of American Avant-Garde Film, Is Dead at 96,” New York Times, January 23, 2019. Alex Greenberger, “Shigeko Kubota, a Fluxus Artist and a Pioneer of Video Art, Dies at 77,” ArtNews, July 28, 2015. The Art Story, “Fluxus.” The Art Story, “Louise Bourgeois.”

3. Lawrence Chatman, “Reggae Rising: Hip- Hop’s Roots in Reggae Music,” Northwest Folklife. NPR, “Tito x 2: Celebrating the Kings of Mambo Again,” November 11, 2009. Jon Pareles, “‘Rhythm & Power’: A Little Bling, a Little Politics, a Lot of Salsa,” New York Times, June 15, 2017. NYPL, “Puerto Rican Traveling Theatre Records, *T-MSS 1994-029 Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library.”

4. CUF analysis of data from U.S. Census American Community Survey, 2014–2018.

5. Council of Fashion Designers in America and FWD.us, “Alterations for an Outdated Immigration System,” May 2018.

6. Whitney Museum of Art, “Whitney Biennial 2019.”

7. The Bessies, “The 2019 Bessie Awards.”

8. MOMA: Film Society Lincoln Center, “New Directors, New Films 2019 – Films.” Tribeca Film, “Here are the Winners of the 2019 Tribeca Film Festival’s Juried Awards,” May 2, 2019.

9. Rowan Anderson, “10 NYC-Based Fashion Designers to Know About,” Culture Trip, January 25, 2018. Council of Fashion Designers of America, “2018 CFDA Awards.”

10. Rasu Jilani, E-mail interview, New York, NY, December, 2019. Katie Cox, “Exploring the Metropolis Announces Shutdown, Redtail Artist Residencies to Continue Legacy,” Exploring the Metropolis, July 27, 2020.

11. Shelley Worrell, E-mail interview, New York, NY, March, 2020.

12. Lindsay Holcomb, “Melting ICE: New Sanctuary Coalition Activists Surround New York Immigrant Processing Center, Calling for Justice,” December 20, 2017. New Sanctuary Coalition, “A Suitcase.”

13. Joseph Mellilo, Phone Interview, New York, NY, April 2019. Megan Bandle, In-Person Interview, Brooklyn, NY, March 2019.

14. MOIA, “State of Our Immigrant City: MOIA Annual Report for Calendar Year 2018,” March, 2019. CUF analysis of data from U.S. Census American Community Survey, 2014–2018.

15. Julie Koo and Mireya Guerra, “Advancing Immigrants. Dance. Arts,” Dance/NYC, July 31, 2019.

16. Milton Xavier Trujillo, Phone Interview, New York, NY, May 2019. Charles Rice-Gonzalez, Phone Interview, New York, NY, April 2019. Local Project, “About Us.” Johnny Farraj, Phone Interview, New York, NY, June 2019. Eli Rosenberg, “Spanish on the Shelves, Latin Culture in the Air at a Bookstore in Queens,” New York Times, July 31, 2016. Rose Kingston, Phone Interview, New York, NY, March 2020.

17. The data used for this report was provided by SMU DataArts, an organization created to strengthen arts and culture by documenting and disseminating information on the arts and culture sector. Any interpretation of the data is the view of Center for an Urban Future and does not reflect the views of SMU DataArts. For more information on SMU DataArts, visit www.culturaldata.org. The DataArts database allows each organization to answer, yes or no, whether they serve a particular ethnic group constituency. Of the 1,373 New York City arts and culture organizations with profiles between the years 2016 and 2019, 70 did not answer, while 188 organizations answered “yes” and 1,115 answered “no.” We analyzed these 1,303 answering organizations, including them in each data query only when the organization’s answer was recordable. We calculated the average of total fixed assets for the 500 non-ethnic organizations as well as the 57 ethnic organizations that answered. For all other data queries, there was a range of between 1,000 and 1,303 answering organizations.

18. National Endowment of the Arts, “National Endowment for the Arts Appropriations History,” Accessed October 2020.

19. NYSCA, “NYSCA Grant Search.”

20. NYC Open Data, “DCLA Programs Funding.” Downloaded October 6, 2019. We looked at every organization listed in “DCLA Program Funding” in 2018 with a DataArts profile, and checked whether it self-identifies as an organization serving a specific ethnic constituency.

21. Data from each Borough Arts Council.

22. New York City Council, “Hearing on the Fiscal 2015 Preliminary Budget & the Fiscal 2014 Preliminary Mayor’s Management Report - Department of Cultural Affairs,” March 11, 2014. Office of Management and Budget, “Expense, Revenue and Contact Budget - FY 2020,” June 2019. CreateNYC, “CreateNYC Action Plan,” July 2019. DCLA, “NYC Department of Cultural Affairs Announces Awards to 36 Nonprofits through CreateNYC Language Access Fund,” January 7 2020.

23. ART New York, “Updates on the DCLA Budget Hearing,” July 9, 2020.