This is an excerpt. Click here to read the full report (PDF).

As more and more New Yorkers turn to digital books, Wikipedia and other online tools for information and entertainment, there is a growing sense that the age of the public library is over. But, in reality, New York City’s public libraries are more essential than ever.

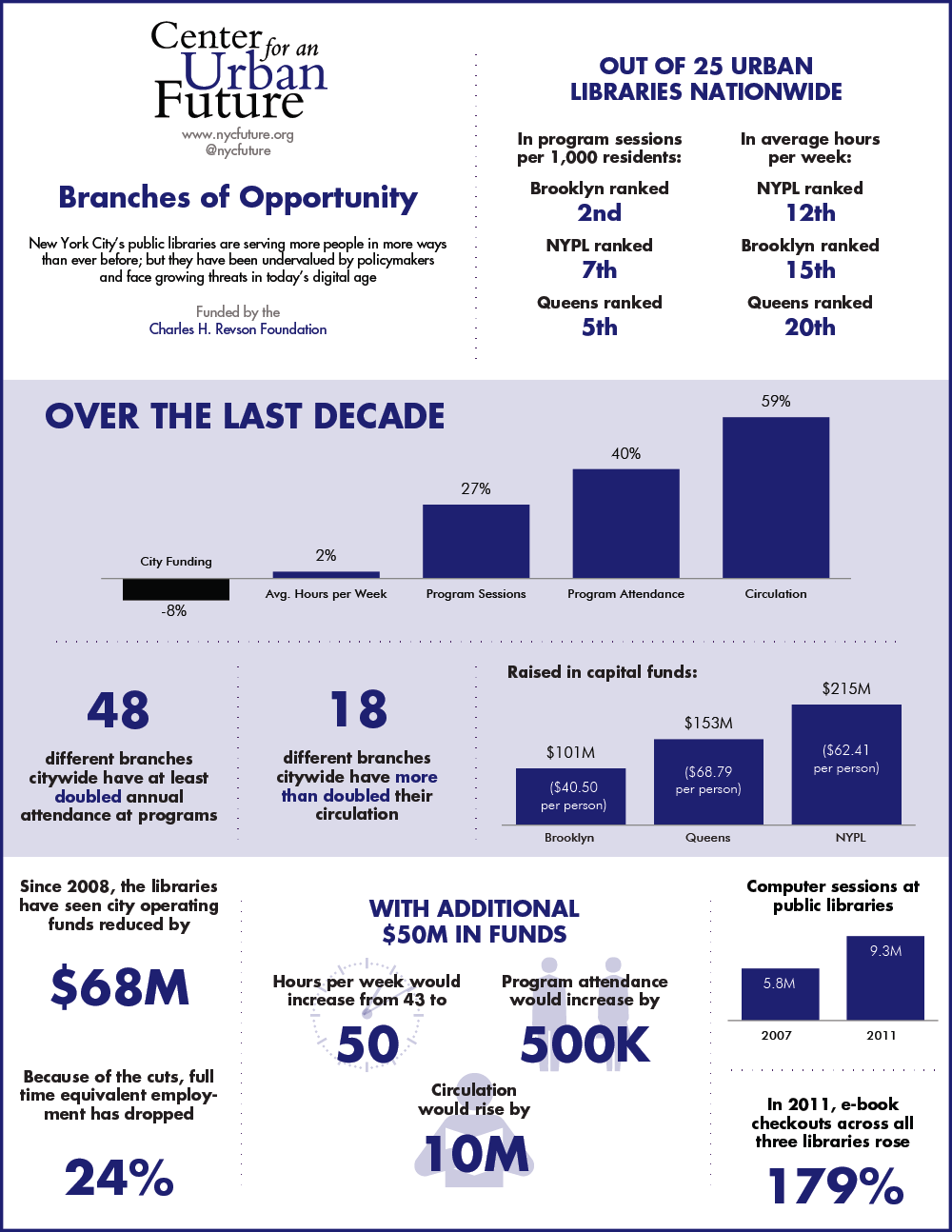

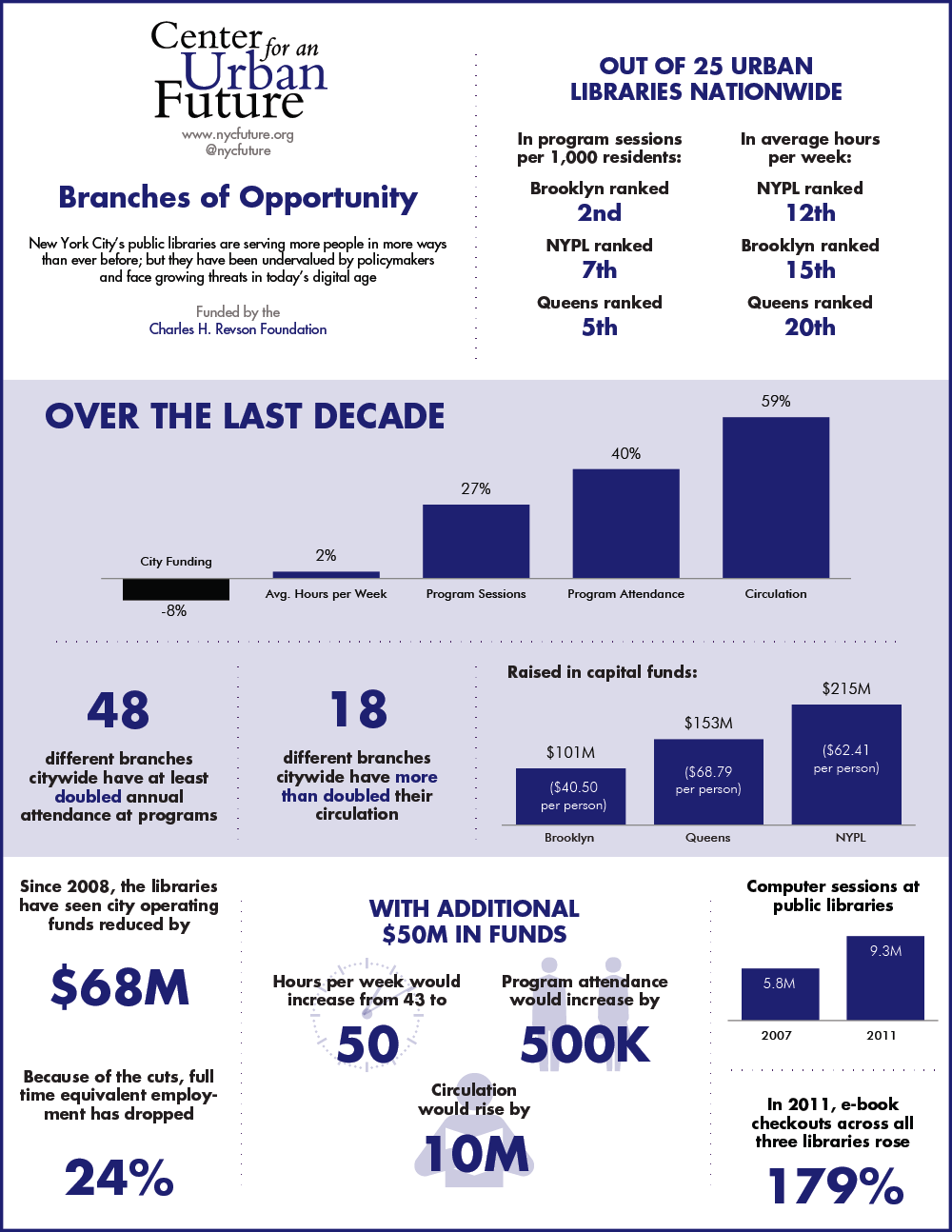

Far from becoming obsolete, the city’s three public library systems—Brooklyn, Queens and New York, which encompasses the branches in Manhattan, the Bronx and Staten Island—have experienced a 40 percent spike in the number of people attending programs and a 59 percent increase in circulation over the past decade. During that time, 48 different branches citywide have at least doubled annual attendance at programs, ranging from computer literacy classes to workshops on entrepreneurship, while 18 have more than doubled their circulation.

These trends are grounded in the new realities of today’s knowledge economy, where it is difficult to achieve economic success or enjoy a decent quality of life without a range of basic literacy, language and technological skills. A distressingly large segment of the city’s population lacks these basic building blocks, but the public library has stepped in, becoming the second chance human capital institution. No other institution, public or private, does a better job of reaching people who have been left behind in today’s economy, have failed to reach their potential in the city’s public school system or who simply need help navigating an increasingly complex world.

Although they are often thought of as cultural institutions, the reality is that the public libraries are a key component of the city’s human capital system. With roots in nearly every community across the five boroughs, New York’s public libraries play a critical role in helping adults upgrade their skills and find jobs, assisting immigrants assimilate, fostering reading skills in young people and providing technology access for those who don’t have a computer or an Internet connection at home.

The libraries also are uniquely positioned to help the city address several economic, demographic and social challenges that will impact New York in the decades ahead—from the rapid aging of the city’s population (libraries are a go-to resource for seniors) and the continued growth in the number of foreign-born (libraries are the most trusted institution for immigrants) to the rise of the freelance economy (libraries are the original co-working spaces) and troubling increase in the number of disconnected youth (libraries are a safe haven for many teens and young adults).

Despite all of this, New York policymakers, social service leaders and economic officials have largely failed to see the public libraries as the critical 21st century resource that they are, and the libraries themselves have only begun to make the investments that will keep them relevant in today’s digital age.

One way or another, New York needs to better leverage its libraries if it is to be economically competitive and remain a city of opportunity.

This report takes an in-depth look at the role that New York’s public libraries play in the city’s economy and quality of life and examines opportunities for libraries to make even greater contributions in the years ahead. In the course of our research, we visited more than a dozen library branches in every borough and interviewed well over 100 individuals, including advocates for immigrants and the elderly, librarians and library administrators, education experts, nonprofit social service providers, entrepreneurs, economic development leaders and library patrons. As part of the report, which was funded by the Charles H. Revson Foundation, we also reached out to innovative thinkers in the technology, publishing and design communities in order to better assess how libraries might leverage structural changes in the economy to innovate and improve.

The idea that the iPad or the Internet will come to replace the library as the dominant mode of accessing books and other information is a deeply intuitive one.The Internet is without question the single biggest driver of economic growth and change in recent history, and the number of services that rely on it has grown exponentially in just a few years. E-book sales, which already comprise nearly a fifth of all book sales, are growing exponentially, and a number of prominent universities and non-profits are building out sophisticated online learning programs. With so many resources readily available online, it is not surprising that some question whether there is still a role for public libraries.

Our research suggests that this couldn’t be further from the truth, just as the widespread claim in the early 1990s that telecommunications technologies would render cities obsolete has proved to be way off the mark. Indeed, we find that, in today’s information economy, libraries have only gotten more important, not less.

“The libraries are much more important today than ever,” says Mitchell Moss, a professor of urban policy and planning at NYU. “They get old people during the day and they get young people after school. [In many city neighborhoods] they are now the only institution where kids can go after school that is safe.”

Data collected from the city’s three public library systems certainly suggest that libraries are increasingly important in New Yorkers’ lives. In Fiscal Year 2011, the city’s 206 public library branches greeted over 40.5 million visitors, or more than all of the city’s professional sports teams and major cultural institutions combined. They offered more than 117,000 different public programs, a 24 percent increase since 2002. More tellingly, the number of attendees at those programs shot up by 40 percent, from 1.7 million in 2002 to 2.3 million in 2011. Although some have questioned the need for material collections, circulation is up 59 percent, going from 43 million materials at the beginning of the decade to 69 million—another record. Meanwhile, libraries answered 14.5 million reference queries in 2011, and library patrons logged 9.3 million sessions on library computers and 2.2 million sessions on their own computers over library WiFi networks.

In the Bronx, the borough with both the highest poverty rate and unemployment rate, 19 of the 35 branches at least doubled their attendance since 2002, while nine branches did the same with their circulation numbers. “The libraries are of critical importance to under-served youth and adults,” says Denise Scott, the managing director of the New York City program for the Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC).

Overall, high performing branches across the five boroughs include large regional libraries such as Brooklyn Central, Kings Highway, Mid-Manhattan, the Bronx Library Center and of course Flushing, which has one of the highest branch circulations in the U.S. But dozens of much smaller neighborhood branches across the city attract tens of thousands of patrons as well, including High Bridge, Forest Hills, Jackson Heights and McKinley Park. Despite having only 8,000 square feet, circulation at McKinley Park in Brooklyn last year topped out at over 950,000 materials, making it the seventh most popular branch for checkouts in the city.

In terms of basic user metrics like circulation and programming, New York’s libraries compare favorably with other big city systems. Out of 25 large urban library systems that we consider in this report, Brooklyn ranks first, NYPL second and Queens third in total number of programs offered. And, on a per capita basis, only Columbus provides more programs than Brooklyn (ranked No. 2), while Queens and the NYPL rank No. 5 and No. 7 respectively.

Meanwhile, New York’s three systems all experienced higher program attendance levels than any other system except Toronto. In fact, the program attendance at the city’s top five branches in that category—Brooklyn Central, Kings Highway, Flushing, The Bronx Library Center and Forest Hills—was higher than the system-wide attendance in 12 other cities, including Charlotte, Detroit, Jacksonville, Baltimore, Boston and Phoenix. The New York systems do less well in terms of circulation per capita. Yet out of 25 systems, both Queens and NYPL are still in the top ten, while Brooklyn comes in at No. 11.