Late last month, Mayor de Blasio’s Jobs for New Yorkers Task Force released its long-awaited report spelling out the administration plans to revamp the city’s workforce development system. The report, titled Career Pathways: One City Working Together, is ambitious, thoughtfully written, and solidly based on evidence of effective practices. Its 10 recommendations can be collectively understood as a vision for how New York City will make skilled human capital available to employers in the 21st century, while giving disadvantaged city residents an equitable opportunity at good jobs.

If the city successfully implements Career Pathways, young people and adults will see clearer and more achievable routes to career success, city agencies will transform the way in which they relate to their clients and to one another, and the City University of New York (CUNY) will become a more powerful and effective agent for economic mobility.

But the Career Pathways vision will require major cultural changes, especially at CUNY’s network of community colleges. Unless the de Blasio administration moves boldly and strategically, the paradigm shift they seek could slip away into the perpetual future. This commentary lays out four recommendations that we think could help the de Blasio administration fulfill the promise of its bold new vision.

The need for a career-focused system is clear. New York City’s education and workforce development programs do not fit together well, and some are still designed for an earlier era, when high school diplomas unlocked the door to stable, family-supporting jobs. Those jobs have evaporated over time, as employers computerized their operations and sent routine work overseas. Today, it’s hard for any New Yorker to get out of poverty—or stay in the middle class –without a postsecondary credential. That means P-12 education and workforce institutions have to pave the road to college and other opportunities beyond the high school level. They also need to develop second-chance strategies for the New Yorkers who left high school before graduation. One in five New York City residents over age 25 lack a high school diploma, as do one in eight residents between ages 21-24.

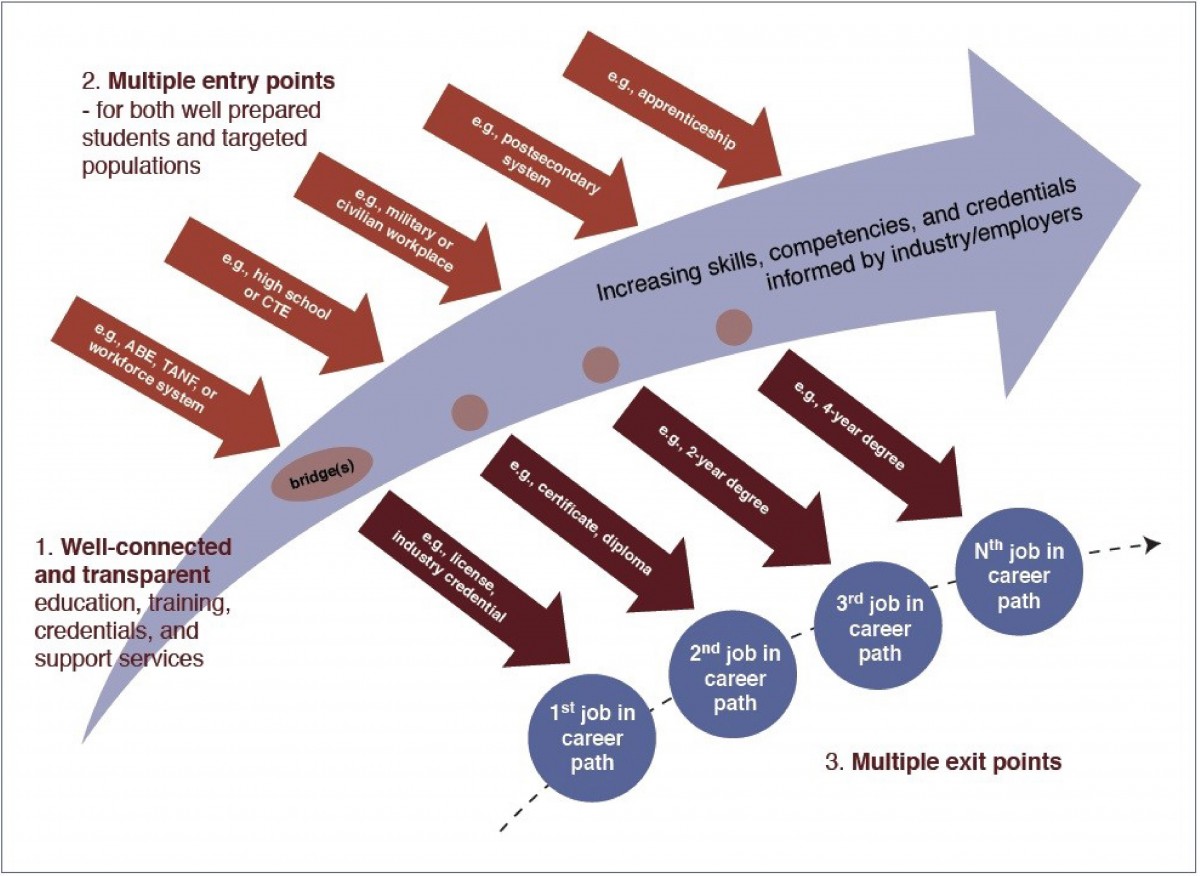

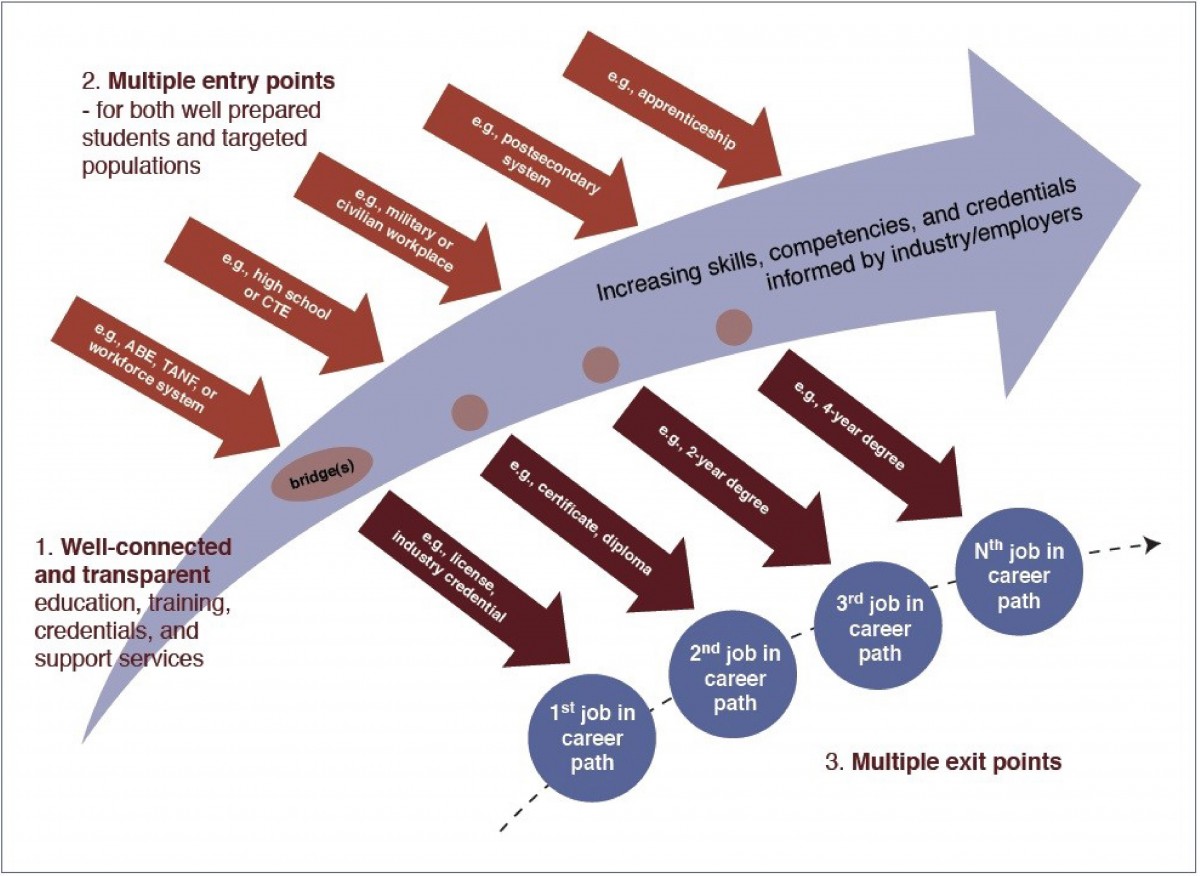

The heart of the Jobs for New Yorkers (JFNY) vision is its second recommendation: “Establish Career Pathways as the framework for the City’s workforce system.” The term “Career Pathways” refers to an approach for connecting progressive levels of education, training, support services and credentials in a way that optimizes the progress and success of individuals with varying levels of abilities and needs. Career pathways connect occupations within a given economic sector. Individuals can enter at multiple points to obtain education and training services, exit at multiple points to work at the jobs for which they have been prepared, and enter again to obtain the education or training necessary for the next step on the pathway. Crucially, each of these services should be well-connected to one another and visible to the people who work their way along the pathway. See chart below.

Essential Features of Career Pathways

Source: Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP)

The career pathways approach offers the CUNY community college system a central role. Community colleges are the main providers of the education and training that prepares students for middle-skill jobs—that is, jobs that require more than a high school diploma and less than a bachelor’s degree. In addition, CUNY also provides continuing education, adult literacy and English as a Second Language (ESOL) instruction that can reach New Yorkers who are far from college readiness, and in many cases lack a high school diploma or equivalency credential.

Importantly, the Jobs for New Yorkers Task Force puts significant funds behind its Career Pathways framework. The report commits the administration to tripling the city’s spending on training for career-track, middle-skill occupations to $100 million annually and to investing $60 million annually in bridge programs that prepare low-skill jobseekers for entry-level work and middle-skills job trainings. Much of this new funding can and should go to CUNY. But the potential funding comes with expectations. The report calls on CUNY to carry out at least three major upgrades in its capacity to support working students:

-

Expand bridge programs. The report calls for the broad implementation of bridge programs, which prepare students to take high school equivalency exams (HSEs) while also preparing them for careers in an occupational sector, such as health care or business. Career Pathways points to the bridge program operated by LaGuardia Community College as a model of proven effectiveness. Students in LaGuardia’s Bridges to Health and Business courses are far more likely than in traditional programs to complete the course, pass their GED (now called TASC) exam, and to enroll in a community college program after completion. The report also calls for adding a career element to existing basic education programs.

-

Improve transfer and alternative experience credit systems. The report calls on CUNY to grant academic credit for students in training courses and also for their life and work experience. This means, first, that colleges should assign college credit to courses in continuing education that meet standards of academic rigor. Kingsborough Community College already does this with a system of “banked credits.” Second, the report calls on community colleges to provide credit for prior learning, so that students with relevant life and work experience can be assessed and granted credit for their experience. In both cases, the goal is to accelerate student progression into academic study and avoid wasting time and money on duplicative courses.

-

Modernize and expand career counseling. The report calls on CUNY to expand career counseling. Critically, the model cited breaks from traditional career counseling, moving to an updated approach that incorporates real-time labor market information, career pathways and direct employer engagement.

CUNY has a head start in implementing these initiatives because of the work already done by two colleges, LaGuardia and Kingsborough. LaGuardia has pioneered the bridge program model endorsed by the JFNY Task Force, as well as the NY-BEST model, which connects basic skills instruction with postsecondary skills instruction for students who have already earned their high school diploma or equivalency. Kingsborough has led the way in aligning their continuing education programs with employers in hospitality, food services and community health care, and in bringing workforce instructors into the same room with faculty of credit programs. Both colleges have become national models.

A federal grant has enabled CUNY to establish the Career PATH initiative, which spreads employer-aligned education and training to CUNY’s other five community colleges. As a result, the city’s community college network is better prepared than it would have been five years ago to respond to the JFNY Task Force’s call to arms.

Despite the promise, the new system envisioned by Career Pathways is still far away. Linkages to employers, workforce programs and social service providers have yet to be built in any systematic way, the bridge programs are still few and fragmentary, and most CUNY community colleges do not offer banked credits or credit for prior learning.

What the de Blasio administration aims for is no less than a culture change—at city agencies, among service providers, and at CUNY’s community colleges. To accomplish this, the city will need to do the following:

Confront the costs of change. The JFNY report calls for major increases in spending on workforce training. But not all training is created equal. Short training programs typically lack any basic skills instruction, and their benefits may not last very long. Likewise, traditional preparation for high school equivalency exams is less expensive than the bridge model, but with much weaker completion, pass rates and college transition outcomes. Yet more effective models have been neglected because they cost more. Typically they require full-time instructors, career counselors, and big upfront investments in professional development. If the city cuts corners, the model could fail to perform as expected.

The city should conduct detailed return-on-investment studies to determine which models produce the best outcomes at the most reasonable cost, and then invest in them. Bridge programs, to take the most obvious example, cost more to operate—but if we took into account their remarkable success rate, they would almost certainly appear much less expensive than traditional HSE prep programs.

Other long-overdue reforms, such as credit for prior learning and bankable credits, are tough for community colleges to afford because they eliminate courses for which the colleges receive payment. The administration should push forcefully for its priorities, while at the same time accommodating the financial imperatives of its partners.

Focus on both improving outcomes and expanding access. Anyone who has worked in the trenches of education or workforce training knows that big reforms often lack staying power. The only way to succeed over the long term is to identify the outcomes that really matter, rigorously track those outcomes, and use them to improve practice on the ground and to guide funding decisions. That feedback loop will be especially important to the Career Pathways vision, which calls on higher ed institutions and community-based organizations to make fundamental changes. Transparent information on outcomes will show how far they have gotten. But there is also an accountability trap. Insisting on rigorous outcomes can encourage service providers to “cream,” a practice in which the provider chooses the easiest clients to serve and avoids those who are harder or riskier to serve. The city must therefore impose clear standards on the target population to be served—especially for bridge programs, which should create opportunities for clients who read and write at a 7th to 9th grade level.

Develop a plan to support the career aspirations of working adults. The JFNY report shows that the city has already made significant progress mapping out a strategy to support the career aspirations of young people. But adults are harder to support, because they are already in the workforce and lack established institutions that support their income mobility. The city, perhaps with leadership from the Center for Economic Opportunity, should develop a fully articulated plan to reach out to working or unemployed adults and connect them to opportunities to start a career pathway—or to get back on track with one. One important component is to make employment and education outcomes consistent across all programs, especially adult literacy, as Washington State already does. A second component would be to work with the Governor and State Legislature to overhaul its adult literacy funding stream, the Employment Preparation Education (EPE) Program. EPE has been outdated for years, and it is now entirely inconsistent with the career focus established by the federal government in the 2014 Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act.

Focus on employer needs. The most important breakthrough of the Bloomberg Administration was to reorient workforce development programs around the needs and expectations of employers. Those gains should be built upon, not only through the industry partnerships proposed by Career Pathways, but through relentless use and dissemination of labor market data. In this way, service providers can align their services to the needs of employers and avoid training disadvantaged youth and adults for nonexistent jobs. At the same time, it is important to keep in mind that employers do not necessarily want applicants for middle-skill jobs who have received only vocational training. On the contrary, they need employees who can write well, solve problems, collaborate with other employees and communicate with customers—in short, 21st century skills that cannot be programmed into a computer. A higher ed institution that fails to provide a strong liberal arts education risks losing touch with the real needs of today’s employers.

The de Blasio administration’s strategy to reorganize the city’s human capital programs through a career pathways approach makes sense. And it is hardly uncharted territory. Other cities, like Milwaukee, Louisville, Portland and Seattle are already using career pathways and other strategies proposed in the JFNY report. But successfully implementing these approaches in a city as big and complex as New York City will require a balance of bold experimentation, pragmatism and patience.