1. Introduction

2. Unprecedented demand and lengthy waiting lists for basic workforce education and English classes

3. Understanding the causes of New York City’s growing demand

4. Five key obstacles preventing organizations from meeting immigrants’ needs

5. Recommendations

In the coming months, if all goes according to plan, tens of thousands of asylum seekers who arrived in New York City over the past year will receive their official work authorization and begin the process of looking for employment. This massive influx of new workers could be a major boon for the city's economy at a time when the city's population has shrunk by an estimated 468,000 since 2020 and when many employers have been struggling to fill positions. Right now, however, it's far from clear that New York's workforce training infrastructure has the capacity to help these newcomers—most of whom lack English proficiency and industry-specific skills or credentials—to seamlessly transition into employment.

Even before the pandemic, New York City was struggling to help many of the city’s 2.79 million working age foreign-born residents—including over 1.4 million who have limited English proficiency—with job training, workplace certifications, learning English, and connecting to other supportive services that will help them get on the path to employment. Now, more than 110,000 asylum seekers have arrived since last spring, with tens of thousands settling here with no family or employment connections, and the city is significantly further behind. Policymakers hope that these new New Yorkers will receive federal work authorization in the next year—or state work permits even sooner—but the city’s network of workforce development providers will not be fully prepared to support them unless new investments are made.

While the city and state have admirably devoted more than $1.7 billion to provide emergency shelter for nearly 60,000 asylum seekers at a time, effectively doubling the city’s shelter capacity, there have been too few resources committed to the literacy and training infrastructure that will help this latest wave of newcomers become productive New Yorkers.

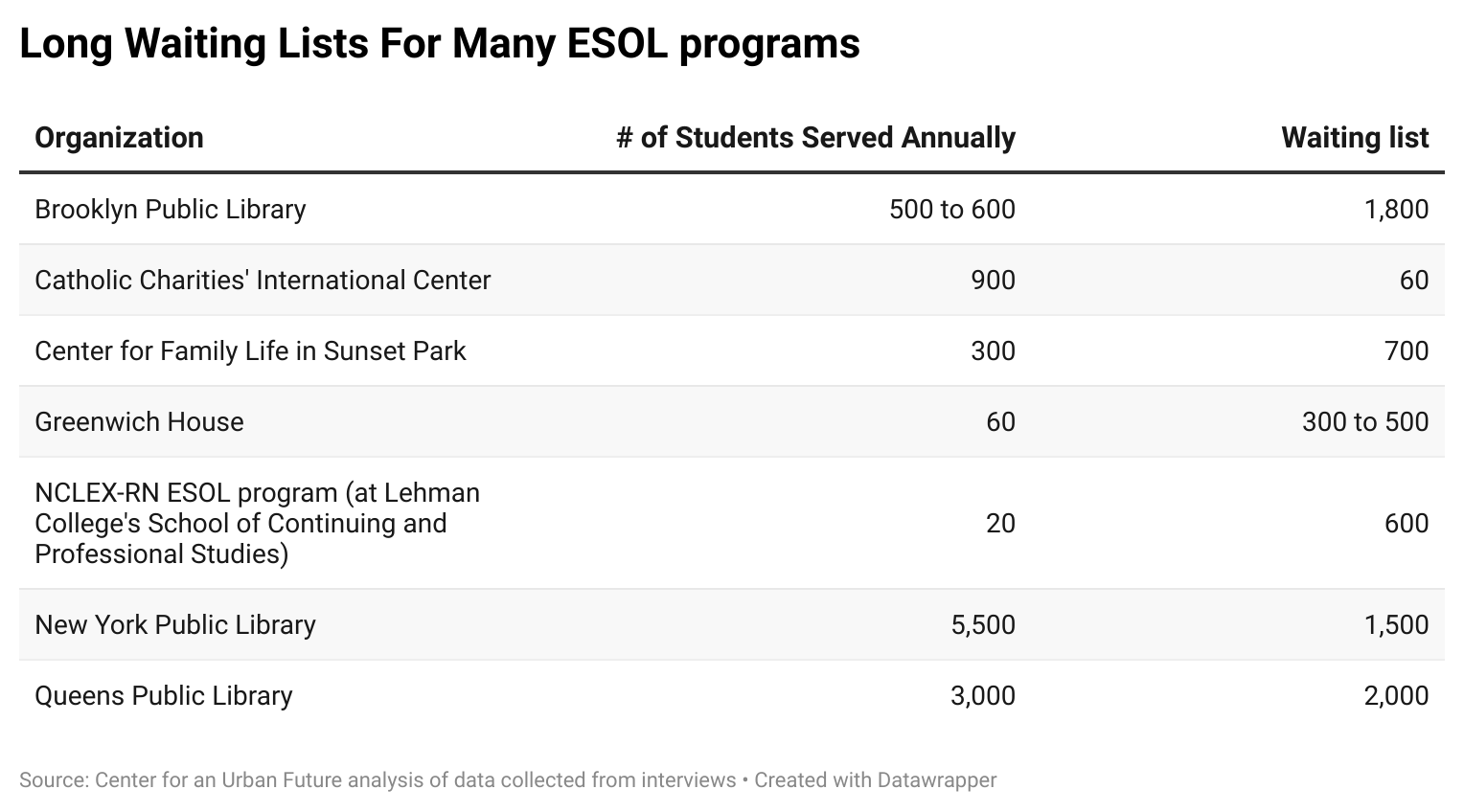

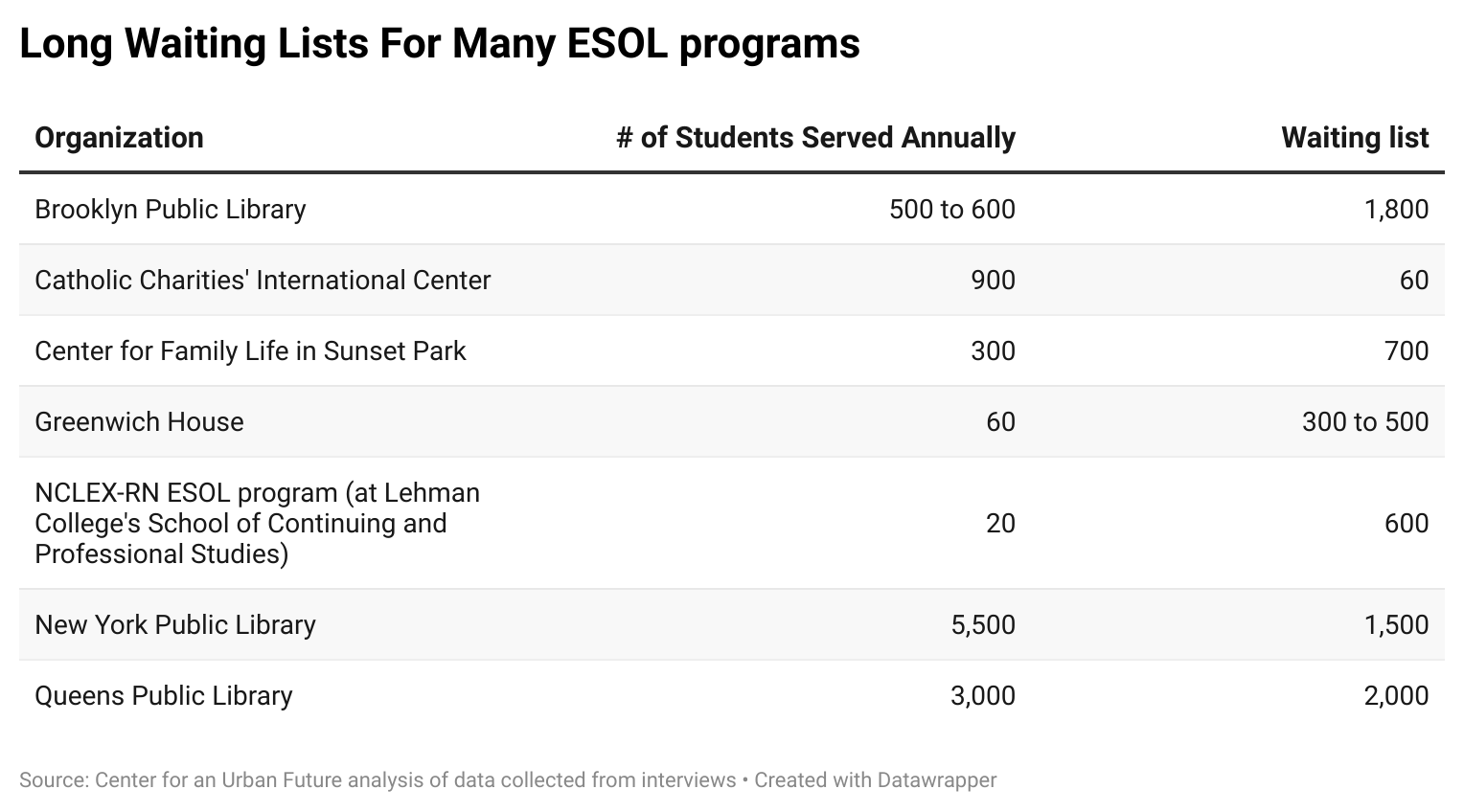

Thirteen of the nonprofits interviewed for this report—more than half of those we reached out to—said that their programs have waiting lists, with each commonly turning away hundreds of people. One program at Lehman College, which assists immigrant nurses with improving their English language skills and gaining certification and employment, has had 600 applicants for 20 spots. New Immigrant Community Empowerment, a Jackson Heights organization, reports a waiting list of between 300 and 400 people for the basic classes needed to be eligible for work on construction sites. Similarly, the Center for Family Life in Sunset Park enrolls 300 people in its English for speakers of other languages (ESOL) programs each year, but recently had more than 700 people on its waiting list, while Manhattan-based Greenwich House has capacity for 60 students in its ESOL program, but has 300 to 500 on its wait list. Some organizations do not even maintain waiting lists because they give out “false hope.”

During a July information session day at New York Public Library’s Stavros Niarchos Foundation Library in Midtown, where there was capacity to register 300 patrons for the library’s ESOL classes, lines began forming four hours before the session began. Once the session capacity was met, approximately 200 additional people were turned away. At just one branch of the Queens Public Library—the Flushing Adult Learning Center—there are 1,000 people on their ESOL waiting list for the past six months.

“[Even] prior to the [recent] arrivals, our waitlists made me cry,” says Patricia Mullen of Lehman College’s Adult Learning Center.

Demand is highest for English language learning, workforce development classes taught in languages other than English, digital literacy classes, and certifications in several industries that are traditional immigrant pathways, including hospitality and construction. The Queens Public Library reports a 50 percent increase in interest in digital literacy classes in recent months, and most of the interest is from immigrants.

Much of the problem comes down to inadequate resources. "So many workforce providers that are meeting the needs of immigrants who have work authorization have long waiting lists,” says Gregory J. Morris, chief executive officer of the New York City Employment and Training Coalition (NYCETC), an organization that advocates for many of the city’s workforce development providers. “At the same time, workforce providers are also doing all they can to support those who don’t have work authorization, but they don’t have resources to do that work. Our city has focused on food and shelter for migrants—and rightfully so—but we have to build the on-ramp to work, too.”

Funding for workforce development specifically designated for immigrants is not clearly tracked, as it comes from allocations via many different federal, state and city sources. While there have been investments in new and continuing programs for immigrant jobseekers at the city level, none have come close to reaching the scale of the need among immigrants who will be seeking jobs. Providers also say they do not know from year to year what their funding will be, and there are months each year when they let go of staff and do not offer training while waiting for public funding to be allocated and deployed.

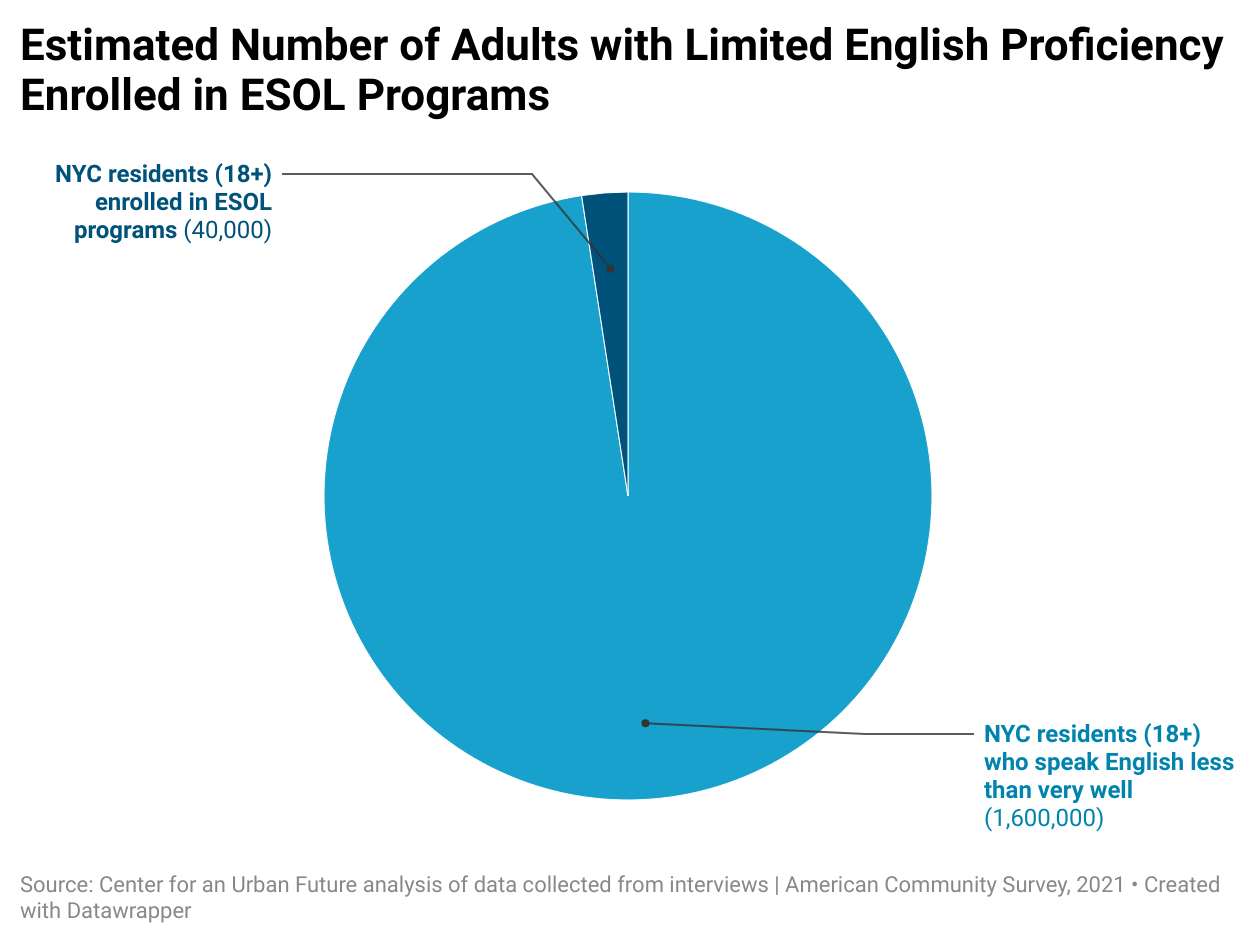

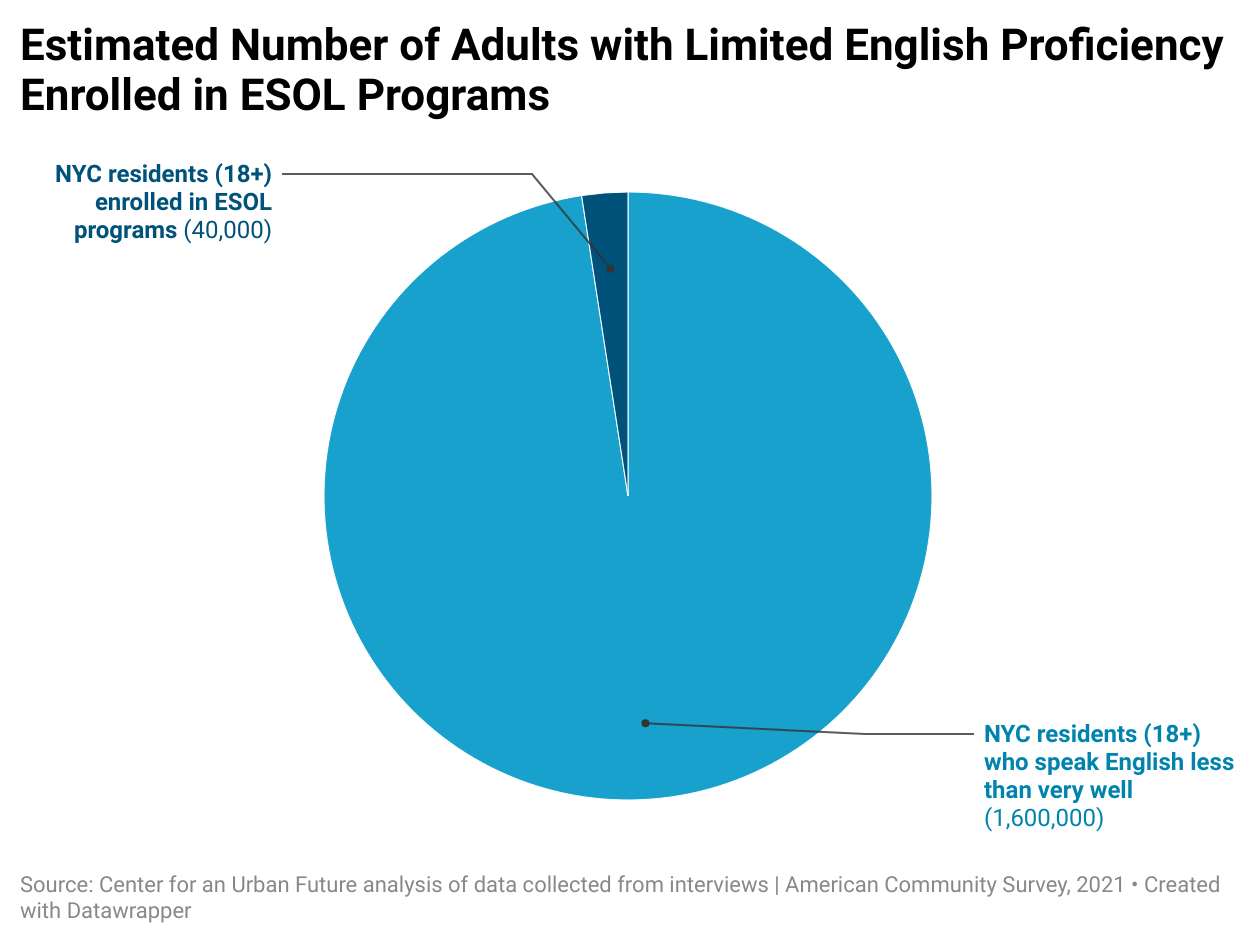

Funding for English classes does not meet the needs of those who reach out to programs directly—as evidenced through long lines and even longer waiting lists—and barely accounts for the broader needs of New Yorkers with low English proficiency. Experts estimate only 40,000 of the 1.6 million people over 18 take ESOL classes each year in New York City. The New York City Coalition for Adult Literacy reports that city and state funding combined is so inadequate that fewer than 4 percent of all adult New Yorkers who could benefit from literacy education are able to take classes each year.

“This is also a basic human right: to be given an education in the dominant language of the society that you are in so that you can achieve security and stability more fully,” says Ira Yankwitt, executive director of the Literary Assistance Center, a nonprofit that supports the adult education system. “This is a good investment in our city.”

Funding adult basic education, high school equivalency, and ESOL comes from several sources, including the federal government (about $47 million for New York state); the state ($9.3 million specifically for adult literacy education through community based organizations, volunteer organizations, colleges and libraries, and a larger $96 million fund spread across the state’s unions, school districts, and Boards of Cooperative Educational Services); and the city ($23.3 million in the 2024 budget for community based organizations, which is an 11 percent cut from the year prior). By comparison, the city reported that it is spending $9.8 million per day on shelter, food, and medical care for immigrants.

On top of the basic shortage of seats, there are other obstacles. One key challenge is that few of the city's workforce organizations that serve immigrants have the capacity to provide instruction and services in languages other than English, leading them to turn people away who are not English proficient.

Stephanie Birmingham, director of community and operations at the New York City Employment Training Coalition, says that 52 of the coalition’s members indicate that immigrants, refugees or asylum seekers are a part of their primary populations served. Despite that, she says, “English is the primary language that the programs are delivered in” and that only “a handful of providers” offer courses in languages other than English, meaning that access to the trainings already requires English skills. One notable exception is the Queens Public Library, which offers an entrepreneurship training program that operates in English and Spanish, and is expanding into Chinese. But very few organizations have that capability.

When applicants are turned away from workforce development programs because they lack English proficiency, they then find that the wait for basic English language classes can be many months or even years long.

Another challenge is that even when immigrants do speak English, funding for workforce development commonly mandates that all program participants already have federal work authorization permits to enroll in training. As a result, the tens of thousands of asylum seekers currently waiting for work authorization—a process that currently takes up to two years—cannot seek training while they wait.

“A lot of applicants who come to us are undocumented. We are unable to enroll them in training because the purpose of our 5-week culinary workforce training is to get people jobs—which requires work authorization,” says Cathy Kim, chief program officer at Hot Bread Kitchen, a Manhattan-based organization that provides culinary industry training.

Kim says that about 40 percent of the roughly 200 women the organization expects to train this year are immigrants, but while the organization has seen strong demand for a newer work-focused English for speakers of other languages course, the organization is having trouble filling it because the people who need the course do not have the required work authorization.

Finally, funding rules rarely allow organizations to offer remote classes or provide wraparound services, which many workforce providers say are necessary to meet the needs of recent immigrants who lack steady income or fixed addresses and are juggling family responsibilities. “You cannot ask someone to come to you for 20 hours a week to learn while they cannot afford to eat or to support their families,” says Fatma Ghailan, director of community learning at Queens Public Library. “Wraparound services are really important to be able to support immigrants.”

To be sure, New York City and State have stepped up in numerous ways to support the ongoing wave of migrants and asylum-seekers. Mayor Eric Adams administration has opened more than 200 emergency shelters, including 15 large-scale humanitarian relief centers. The city has created navigation centers to help connect asylum seekers to support services, enrolled thousands of children in public schools, and helped submit more than 3,000 asylum applications. The “Blueprint to Address New York City’s Response to the Asylum Seeker Crisis,” released in March 2023 by the Adams administration, included a handful of commitments around workforce development, including helping identify asylum seekers who are eligible for work permits, supporting existing industry training initiatives, funding community based organizations to provide adult literacy services at humanitarian relief centers, and offering workplace rights education.

The New York City Council has also taken steps to meet some of the growing demand for workforce development services among the city’s recent arrivals. For instance, the Council’s $2.2 million Welcome NYC initiative—funded in partnership with the Robin Hood Foundation, New York Community Trust, Bronx Community Foundation, New York Women’s Foundation, and Brooklyn Community Foundation—included $100,000 in new funding for community-based organizations to provide workforce development services.

For their part, Governor Kathy Hochul and the State Legislature allocated more than $1 billion in the most recent budget to support the asylum-seeker response effort, deployed the National Guard to help with sheltering needs, and stepped up investment in adult literacy education, among other actions. The governor and State Legislature are also considering options for issuing state work permits directly to asylum seekers. Just this month, the Biden administration

granted temporary protected status to the country’s 500,000 newcomers from Venezuela, allowing thousands of asylum seekers in New York to apply for work authorization.

These commitments underscore the dedication of city and state policymakers to a comprehensive response to the growing humanitarian challenge and signal growing consensus that investments in workforce development and English language learning should form a key plank of a combined city and state strategy going forward.

New York City’s historic role as a beneficiary of and sanctuary for immigrants will be on shaky ground if the city welcomes newcomers without taking sufficient steps to integrate them into the workforce. Meeting this challenge will not require anywhere near the public funding being spent on shelter and other emergency services for asylum seekers, but it demands a rapid increase in resources to expand ESOL programs and dual-language workforce training programs. Since New York City has covered the largest share of the costs for sheltering the tens of thousands of new arrivals, Governor Kathy Hochul and the State Legislature should step up and fund a major expansion of English language classes and workforce training programs geared toward immigrants. Other steps are needed: from loosening eligibility restrictions where possible and allocating more flexible funding to enable job training for clients without work authorization, to new support for wraparound services, remote classes, and an expansion of in-demand certifications in industries like construction and healthcare. Taking these actions will not only expand pathways to employment for New York’s many recent arrivals; they will serve as a crucial investment in the city’s future workforce.

All English for speakers of other languages providers and many workforce development organizations describe demand as “unprecedented” and/or “consistently exceeding capacity.” Programs that do have openings for students typically have entrance requirements that many immigrant participants are unable to meet, such as federal work authorization or high levels of English proficiency. Demand is particularly high for organizations that provide basic English classes, for the few organizations that offer workforce trainings in languages other than English, for digital literacy classes, and for classes that lead to certifications in traditional new immigrant employment pathways—including hospitality, health care, and construction.

Unmet demand for ESOL classes is surging

For this report, the Center for an Urban Future interviewed staff from 24 organizations that provide ESOL and workforce services to immigrants or serve as umbrella organizations for many more organizations that do. Through these interviews, CUF learned that many programs are overwhelmed by the current demand. Of those interviewed, 13 organizations shared stories of waitlists ranging from manageable to extreme—in most cases, these lists were hundreds of people long even before the current wave of asylum seekers. The following examples highlight the unmet demand:

The New York Public Library, the largest non-municipal provider of ESOL, serves 5,500 people annually across 34 branches and still carries a waitlist of 1,500 people the system cannot serve.

The Brooklyn Public Library has had 1,800 people join its ESOL wait list just since April 1, while the system serves between 500 and 600 students per year, according to David Giles, the library’s chief strategy officer.

The Queens Public Library provides ESOL classes to 3,000 people annually and has a waiting list of 2,000. At the Adult Learning Center at the Flushing Library, 500 people came to the library every three days for three months to register for a lottery to receive one of the 75 to 150 seats in its ESOL program, according to front-line staff.

CUNY, which is the city’s largest provider of ESOL classes, also has waitlists throughout its system. At the Lehman College Adult Learning Center, Patricia Mullen says she operates with “razor thin margins” and she gets emotional talking about all the people the Center has to turn away. “Some are willing to wait as long as two years,” she says. “It’s just a horrible, horrible thing.”

At the Center for Family Life in Sunset Park, there are 700 people on the waiting list for a program that serves about 300 people each year.

Catholic Charities’ International Center in the Financial District typically serves about 900 immigrants per year with intensive and lower-level community English classes. The organization has run a city-funded program for nine years, and while it usually takes about six months to fill the program for the year, this year it filled in about half the time, about three months, explains Elaine Roberts, the organization’s director of programs. “We're getting so many people at this point that we're looking at months down the road when we might have space for them. I would say right now we probably have about 60 people on the waitlist for the intensive [ESOL] classes.”

Demand is high for training in jobs traditionally open to new immigrants

Demand for training in traditional new immigrant employment pathways—hospitality, health care, construction, and others—remains very high for many organizations. For example, many new immigrants view construction as a relatively stable source of employment in a city of New York’s size and learn through their networks that two key certifications are required to gain access to most construction jobs. As a result, a growing number of recent immigrants are seeking out the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and the local Site Safety Training (SST) certifications, according to several training providers. A report released earlier this year1 by Associated Builders and Contractors, a construction industry trade group, pointed to an acute shortage of construction workers nationwide, and any push to ramp up desperately needed housing construction in New York will require a large and ready pool of certified workers to get the job done.

There is “a huge amount of people waiting for the OSHA and SST training,” says Nilbia Coyote, executive director of New Immigrant Community Empowerment (NICE)—a nonprofit organization serving immigrants through skills-building programs, worker advocacy, and other services. “We have a waiting list of around 300 or 400 people,” which she says peaked at around 700 before the organization hired additional trainers. According to Coyote, a 40-hour course costs the organization about $6,000 per person, and it is seeking additional OSHA trainers to keep up with demand.

Similarly, the Restaurant Opportunities Center (ROC-NY), a nonprofit organization that advocates for and trains restaurant workers, is able to serve fewer than half of those interested in enrolling in its food handler program. Roughly 200 individuals each year seek out this certification annually, which can provide a boost into the culinary and food service sector, but ROC is only able to serve 80 or 90 people per year, according to Rev. Prabhu Sigamani, director of the organization’s New York chapter. Sigamani estimates that 35 to 40 percent of the organization’s graduates in any given year are immigrants.

“We are not funded by the city nor by the state for any of the training, and particularly for immigrants the need has become bigger and bigger and taller and taller,” says Sigamani. ROC-NY would like to offer other back of the house training and a front of the house training for restaurant workers, but does not have funding to do so.

Providers said that demand for English proficiency classes and basic employment skills stems from several central and interrelated factors: the decline of pandemic-era expanded social programs leading more people to seek work, a tight labor market that is hungry for workers, and the recent arrival of tens of thousands of migrants in current asylum processes and humanitarian parolees from Latin America, the Caribbean, and Ukraine—the term for immigrants who have legally come to the United States to reunite with family as a part of a program for those waiting for visas.

“When the influx of new migrants started last spring, I started seeing a lot of people come in. NICE provides orientations for new members, we used to do it one time per month. Now we do it eight times per month,” says Nilbia Coyote of NICE. Many of the new arrivals weren’t aware of what Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) or Site Safety Training (SST) were or even how to pronounce them, but knew that these were routes to employment in a sector with high labor demand.

Leaders at CAMBA, a Brooklyn-based social services nonprofit that holds federal, state, and local contracts for supporting Ukrainian refugees and other humanitarian parolees, have seen a massive number of new arrivals over the past 18 months. The surge has required CAMBA to triple its workforce development staff, accommodating growth from under 200 participants to almost 900 in programs such as security guard training, OSHA certification, and programs for heating/cooling technicians.

CAMBA also has a waitlist of roughly 250 Haitian parolees, and “that number is growing,” says Dzemal Hamzic, a senior program director with CAMBA. “Today I received three new requests . . . I think that on a daily basis, we have five to 10 new clients from the population of Haitian humanitarian parolees. That is the reason we have a huge waiting list, that we cannot call them on time. But we are the only one who provide them services here in Brooklyn, and until we hire more manpower in this department, it will be really, really difficult to answer to all that demand.”

Beyond increased demand, other factors are interfering with organizations’ abilities to build capacity, including a lack of available space to hold classes; a shortage of administrative staff; long waiting periods for funding which lead to loss of staff; contracts that do not cover the additional costs of running programs targeting immigrants with specific needs, such as legal assistance and enhanced social services; and funding streams that some organizations consider too uncertain or short-term to build out capacity for the long run.

Finally, while many organizations report waiting lists, some report being at or even below capacity. The cause does not appear to be the absence of overall demand, but rather a mix of factors that this report’s recommendations lay out steps to remedy—eligibility constraints, language barriers, and contract inflexibility among them. There is reason to believe that as these issues are addressed, even some programs that are not currently oversubscribed will see an uptick in demand and will also need to increase capacity. In effect, some of the system’s current shortcomings can block access to workforce programs, which means that addressing them will increase demand further, and require concerted efforts and funding now by the city and other entities.

1. English language competency is often a prerequisite for workforce development services, which leaves out many immigrant New Yorkers. But many workforce organizations either lack the capacity to provide job training in other languages or combined ESOL/training courses.

English language proficiency looms large over organizations’ efforts to recruit and retain students. Various organizations of different sizes pointed to it as a crucial antecedent to any effective workforce program.

“[For] some trainings we will insist on [only conducting training in] English because [participants will] have to compete with other English speakers for the job,” says CAMBA’s Hamzic. Training students to join jobs that don’t require English proficiency runs the risk of, in the long term, getting stuck in those jobs, without much possibility for advancement in those or other industries.

Stephanie Birmingham of the New York City Employment and Training Coalition says that coalition members often provide or refer people to legal services or ESOL programs, because people seeking out workforce development programs do not have the English-language skills or work authorization needed to participate. At the same time, some organizations see the need to expand job training to support more non-English speakers. Kevin Tse, deputy director of strategic initiatives and development at the Chinese-American Planning Council, pointed to multilingual training as one specific plank the organization would develop with sufficient resources. “It would be ideal if there was a source of funding to pay for workforce development courses taught in Chinese or in Spanish. I think that would be a success. And then separately, in English courses, to not only focus on language, but to discuss how to talk to your supervisor or prepare your resume.”

Goodwill NY/NJ previously offered a career advancement program for clients with limited English proficiency that was funded by the city’s Human Resources Administration; however, funding was eliminated during the pandemic. Goodwill’s former director of education and partnerships, Kaveh Sarfehjooy, says it would make sense to relaunch as a bridge program for clients eager to pursue job training but who are not yet proficient in English, enabling those individuals to build English-language and job-ready skills in tandem.

2. Eligibility requirements exclude immigrants who do not have authorization to work or lack other required documentation.

With thousands of asylum seekers on track to receive work authorization in the next few months, organizations point out that they are having to turn away people from training who stand to benefit in the near future. Service providers say it makes little sense to force people to wait to begin workforce training that they could be engaging in as they wait for bureaucratic processes to play out. Workforce organizations around the city report routinely having to turn down prospective clients because they are unable to meet the contractual eligibility requirements typically imposed by publicly funded contracts.

“City contracts have very specific rules around the documentation you have to provide. Some of them require proof of income, and it's not documentation that most asylum seekers have available,” says Katje King of the Northern Manhattan Improvement Corporation. “For a large number of folks who are arriving right now, we're not set up to serve them. Our contracts won't allow it.”

“We have an influx of people who are not eligible because of their status, who come in the office and we have to quickly triage those folks,” says Melissa Mowery, senior vice president at CAMBA.

The Center for Family Life maintains a waiting list for services while struggling to help immigrants without work authorization. “We get people that are referred from other organizations, or people that are just walking in, or they come in for other things like the food,” says Maria Ferreira, program coordinator at the Center for Family Life. “Then they see employment services and they come to our office. And unfortunately, we are struggling with that population because there is so little that we can offer in terms of employment [services].” The organization makes efforts to refer people who cannot be served with job training into English classes and case management services, adding strain to those divisions.

Beyond the social security numbers and work authorization requirements that are often required to participate in federally funded programs, contract stipulations requiring documentation like utility bills or having active benefits with the city’s Human Resources Administration can exclude both new arrivals and longtime immigrants, particularly those who are undocumented. The exclusion of many immigrants from workforce programs exacerbates their already precarious financial situation and prevents those who will eventually receive work authorization from getting prepared during the long waiting period. Taken together, these eligibility restrictions can end up highlighting and worsening existing divisions and making public investments less efficient, not more so.

3. Government contracts that require in-person-only instruction limit participation among many immigrants.

Many current city and state contracts obligate workforce development providers to offer fully in-person instruction, even as their own surveys and experiences with clients suggest that having remote and hybrid options helps workers enter and stay in training programs. Not all skills can or should be taught remotely, as some providers are quick to acknowledge, but many other programs could be completed largely or even exclusively online. Program staff have reported positive results from hybrid models, including by providing in-person training during some weeks and then debriefing or providing informational sessions via video.

Elaine Roberts of Catholic Charities’ International Center says that the organization’s programs had offered hybrid models for English classes with the same students attending online sessions and in-person sessions with the same instructor. “In-person [attendance] was half of online [attendance] consistently. All of our students have reported that they like the convenience, the accessibility of the online classes. So forcing a return to in-person only is a big problem.”

Jeanie Tung, director of business development and workforce partnerships at Henry Street Settlement, says that the organization had been able to meet ramped-up demand for some of its programs given the ability to implement a remote option. “There has been more interest in the language, civics, and citizenship classes, and we've been able to accommodate that because they were being taught virtually during the pandemic,” says Tung. “So we increased the number of people we have been able to help get their high school equivalency during that period.”

“Most adult literacy students have children and demands,” says Patricia Mullen of the Lehman College Adult Education Center. “About 75 percent of our students are women: they’re the primary caretaker, but they’re also the cook for the entire family. The latest thing we’ve really experienced, especially post-COVID, is the elder care needs. You know, in our cultures, it’s your obligation to take care of your parents and your grandparents. So these are things that are challenging. Online education is really what adult students need.”

“If virtual service delivery cuts a half hour, 45 minutes each way, not having to travel somewhere, our clients say that more people would prefer that when possible,” adds Andrea Vaghy, chief program officer at the Workforce Professionals Training Institute, which provides training and technical assistance to other organizations that run workforce programs.

4. Organizations that are unable to provide wraparound services lose students who need childcare, food and housing support, legal assistance, and other services.

Organizations also pointed out that one-size-fits-all workforce solutions that may work fine for the broader population are often insufficient to properly serve immigrants given their particular set of needs. In addition to job training itself, immigrants might often need language services, as mentioned above, as well as casework, legal assistance, childcare, and other wraparound services without which they lack the stability or opportunity to even enter or remain in workforce programs.

“In this current situation, asylum seekers that have just arrived, require even more support and assistance than students might have in the past,” says Elaine Roberts of Catholic Charities. “Everything is just so tenuous. Where do they live? Are they able to access food? Are they able to access clothing? They just have a lot more urgent needs than we might have seen earlier.”

Accounting for these needs might drive up some of the upfront costs, but can also provide additional returns on investment by ensuring that immigrants actually benefit from the training they receive. For example, ensuring that trainees can find housing or childcare and apply for work authorization as soon as they are eligible can boost participation and completion rates—and lead to better long-term employment outcomes. This is especially crucial for new arrivals who don’t tend to have any existing ties or support systems2 in the city.

Roberts says that Catholic Charities’ International Center participated in the city’s Adult Literacy Pilot Project for the past two fiscal years, receiving “additional funding not to serve new students, but to more comprehensively serve the students that we have.” She adds, “The idea is to strengthen and enhance our services, which we did by adding more one-on-one time with them, more connection with outside resources and referrals and goal setting and social service referral, everything you can think of. We're probably going to see a small bump in who we've served, but our goal right now, and I think a lot of the adult education community’s goal, is not to just have a treadmill, but when someone comes in, truly try to connect them with what they need and help them stay in the program, which is really labor-intensive.”

A preliminary report on that program3, which provided an average of $650 in additional funding per student over existing baselines, found that it increased graduations, cut down on attrition, added to staff retention, and had other positive impacts.

In response to a 2022 survey4 conducted by the New York Employment Training Coalition, about 140 members pointed to housing services, cash assistance, mental health support, and legal services as the areas where they could least meet demand. Among these organizations, more than 50 self-identify as having immigrants, asylum seekers, and refugees as the primary populations they serve.

The Center for Family Life has structured its programs such that wraparound services are part of all its offerings, including workforce programs. “We sit down with each person to do a comprehensive assessment or an interview on intake to look at what are their circumstances—their income, their location, their family history—and it is an opportunity for us to assess if there are other services that the family could have a need for,” says program coordinator Maria Ferreira. Julia Jean-François, the organization’s co-director, adds that “it’s far more than just job placement. Given the particular needs of our community, which is a largely newly arrived, new immigrant community, we see the issue of employment as involving literacy, acquaintance with an array of social services, basic human services.”

Effectively designing these programs also requires some of the stability that can come from longer-term funding, and some providers would even rather turn down short-term grants to focus on overarching objectives. “Capacity is not something that you just turn a light switch and turn it on or off. I think funders sometimes think that they can stop funding an organization or program, and then come back later and everything is going to be back the way it was. It’s not true. You lose capacity, you lose institutional knowledge,” says Hannah Weinstock, senior director of workforce development at LaGuardia Community College.

5. In turning to growth industries with higher pay, organizations and funders have moved away from some easier options for people to enter the workforce.

One consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic was a crash in many of the employment sectors that served as long-standing sources of jobs for immigrants, such as retail and hospitality. Even as some industries, like restaurants and construction, have bounced back to varying degrees, workforce organizations report that both potential clients and public and private funders have shown reduced interest in these traditional pathways, instead shifting a focus to what are perceived as growth industries with higher pay.

“Funders are more interested in funding training to prepare people for jobs in fields that would pay higher wages and lead to more upward mobility, like in the health care and tech industries,” says Kevin Tse of the Chinese-American Planning Council.

His experience was echoed by Julia Jean-François of the Center for Family Life. “I think we were the fifth-most-affected community by the COVID job loss because so many of the jobs were in domestic work and hospitality, and that's been slow to recover. Given the competition around funding, certainly on the private side, there's a very clear preference for paying for job programs that will leverage high wages. And that makes sense because donors are attracted to that idea, that with their dollar a person will land a $60,000 a year job,” says Jean-Francois. “It's harder for me to understand why government isn't more tuned into this [shift away from traditional immigrant employment pathways] as the most vulnerable community members who have literacy or language barriers to living wage employment are a group that relies on the public sector to help them to make their way in the highly competitive labor market.”

Some organizations are intentionally targeting industries that seem on a path to rapid expansion. The South Bronx Overall Economic Development Corporation (SoBro) pointed to efforts to roll out training for the legal cannabis industry, anticipating the need for staffing at every level.

New Women New Yorkers, for example, is a participant in a recent New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) workforce development program5 focused on clean energy. “What's really interesting with the energy industry is contrary to a lot of perceptions, it's not only engineering jobs. New York has a lot of jobs that are about community outreach, customer service, administration, marketing, sales,” says CEO Arielle Kandel.

Nonetheless, some organizations fear that expansion of these pathways is coming at the cost of support for training aligned with accessible but lower-paid industries. Tse, of the Chinese-American Planning Council, says that “for the city and all the foundations to only move to the tech industry or the industries that are booming, only health care and leaving out the other sectors as well, that might be really devastating for one side . . . it's easier for nonprofits ourselves to shift our targets, but it's a lot harder for community members to make that shift,” as it requires building multiple skill sets when people might just need a job immediately.

“A lot of immigrants who come into this country, the culinary sector is an easy way to get into the workforce and develop social capital,” says Cathy Kim of Hot Bread Kitchen, adding that the organization partners with specific employers to ensure that placements happen in relatively well-paid jobs with good working conditions. “It doesn't have to be the last stop on someone's journey but it could certainly be the first—and there's a lot of demand for labor in the restaurant industry.” The situation has recently led restaurants to increase pay and benefits6, which in turn strengthens the appeal of career training that can lead to the better-paying jobs within the sector.

Demand for training aligned with construction jobs is also increasing.7 As illustrated by NICE’s Nilbia Coyote, many of the city’s new arrivals are seeking opportunities that will get them to work as soon as possible and establish a foundation of financial stability, and industry-specific training is crucial—and legally required for sectors like construction—in order to get there.

New York finds itself at a pivotal moment amid thousands of migrant arrivals and general uncertainty about the city’s economic recovery and configuration in the post-pandemic world. Rather than think of spending on workforce and language training programs as simply a cost, city and state leaders should view it as an investment. Helping both new arrivals and longtime immigrants achieve self-sufficiency and integrate fully into the city’s economic life is a straightforward way to help cut down on future social service costs, add to the city’s tax revenues, alleviate labor shortages, and generally maintain a healthy economy. The recommendations below can help maximize the impact of this funding, but at base the funding needs to be there in the first place.

1. State leaders should make an immediate investment to expand English and dual-language programs.

To address the unprecedented surge in demand for English language classes, Governor Hochul and the State Legislature should provide an immediate funding boost for basic and intermediate ESOL programs run by CUNY, the city’s public library systems, and nonprofit training and literacy assistance organizations, which absorb the bulk of the demand. Since New York City has provided the majority the of emergency funding used to shelter recent arrivals, state leaders should foot the bill for a major expansion of English language classes that enable those with limited English proficiency to access workforce training programs, obtain jobs, and contribute to New York’s future economic growth. The State has already demonstrated a willingness to modestly boost investment in adult literacy programs, but meeting current demand will require a major scaling-up of ESOL infrastructure and capacity.

2. Provide flexible funding for workforce development programs to serve applicants who do not yet have work authorization.

Currently, most workforce training programs are unable to serve immigrants that do not yet have official work authorization. This is a missed opportunity, since the long wait immigrants face when seeking a work permit could be a time for these future workers to access critical training and education programs that will prepare them to obtain jobs as soon as their work authorization comes through. This new source of flexible funding could be focused on training new arrivals to work in more accessible industries, such as construction and hospitality, and ideally paired with support for combined ESOL/job training programs. City and state leaders should also consider loosening eligibility criteria where adherence to federal funding rules is not a requirement—or issuing state work permits—so that more immigrants, regardless of immigration status, are able to participate.

It’s not that all eligibility criteria should be jettisoned, but the restrictions currently in place overwhelmingly exclude immigrants who need training, including not only 100,000-plus recently arrived asylum seekers but also an existing pool of more than 400,000 undocumented immigrants already in the city’s workforce. Some current programs have found ways to conform to certain contractual criteria that would otherwise exclude undocumented immigrants, such as NICE’s method of tracking graduates’ progress and employment in a way that doesn’t utilize social security numbers. While some of the criteria are in place to combat fraud and abuse within the system, new criteria can be designed in such a way that preserves program integrity without effectively barring a significant share of the city’s current and future workforce from participating.

3. Make remote and hybrid courses eligible for city and state funding.

Our research suggests that remote and hybrid job training programs have expanded access to people who wouldn’t otherwise be able to participate, including parents without childcare, people who live far from training sites, those juggling multiple part-time gigs and side hustles, and even those who struggle to afford the cost of a MetroCard, while helping organizations with limited physical training space meet growing demand. But too many city and state government contracts discourage or prohibit remote learning. This should change. New city and state workforce contracts should allow providers to have flexibility in how courses should be structured, ideally with the option of a hybrid model that incorporates in-person and remote components. New publicly funded contracts should also be redesigned to reduce onerous and unnecessarily time-consuming reporting requirements, including the need to fill out duplicative paperwork for a single client’s participation across multiple programs, for example.

4. Greatly expand support for wraparound services in workforce programs.

Our research indicates that even a free career training program can feel completely out of reach for many low-income immigrants, especially recent arrivals who have little opportunity to earn income and are simultaneously juggling family caregiving responsibilities. Workforce providers say that serving these New Yorkers in need increasingly requires the ability to provide a range of wraparound supports—including child and elder care, transportation supports, mental health services, financial counseling, and legal assistance. Unfortunately, organizations’ capacity to do this is constrained by the striking lack of public sector resources devoted to meeting these challenges within the city’s workforce development systems. City and state agencies that provide resources for workforce development should create a pilot program that offers funding for wraparound services and invest in scaling up models that demonstrate the greatest success in enabling clients to enroll and succeed in training programs, such as the Adult Literacy Pilot Project.

5. Maintain resources for programs that offer training in the industries most accessible to recent immigrants.

The impulse to channel resources toward programs for immigrants aligned with growing, high-wage industries is logical: funders want their limited dollars to help achieve the greatest economic mobility gains possible. However, this shift should not result in the loss of programs that are effective in helping immigrants with multiple barriers to employment to land a job quickly, which can be a lifeline for new arrivals in particular. Government agencies and philanthropic funders should continue to support organizations that offer programs training immigrants in culinary arts, construction, home health care, and other industries that provide a reliable pathway into employment with relatively few barriers, while supporting newer programs aimed at helping immigrants advance into better-paying positions in those accessible industries.

Endnotes

1 ”Construction Workforce Shortage Tops Half a Million in 2023, Says ABC,” Associated Builders and Contractors (ABC), February 2023, https://www.abc.org/News-Media/News-Releases/construction-workforce-shortage-tops-half-a-million-in-2023-says-abc.

2 ”Commentary: The arrival of asylum-seekers is unlike previous migration waves,” Felipe de la Hoz, City & State New York, February 2023, https://www.cityandstateny.com/opinion/2023/02/commentary-arrival-asylum-seekers-unlike-previous-migration-waves/382845/.

3 The Literary Assistance Center (LAC), "Strengthening Adult Literacy Education: Results from the NYC Pilot Project Fiscal Year 2022," January 2023.

4 NYC Employment and Training Coalition (NYCETC), “New York City’s Workforce Landscape, A network of programs, providers, and organizations foundational for catalyzing a robust and equitable economic recovery,” September 2022.

5 New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA), “Workforce Development and Training,” https://www.nyserda.ny.gov/All-Programs/Clean-Energy-Workforce-Development-and-Training.

6 “Restaurants address the labor shortage with better pay, benefits and culture,” Cara Eisenpress, Crain’s New York Business, April 2022, https://www.crainsnewyork.com/hospitality-tourism/nyc-restaurants-fight-labor-shortage-better-pay-benefits-culture.

7 “NYC construction spending reaches all-time high of $86B,” Sebastian Obando, Construction Dive, October 2022, https://www.constructiondive.com/news/new-york-construction-spending-all-time-high-86-billion-building-congress/634872/.