More New Yorkers than ever are enrolling in universities and community colleges, driven by seismic changes in the economy that have made postsecondary credentials nearly indispensable for today’s workforce. But on college campuses across the state, the makeup of the student body has changed. College is no longer just for “traditional” students who graduate high school at age 18, enroll directly in college, and are financially supported by family. Today, much of the growth is occurring among nontraditional students—people who are over the age of 25, enrolling part-time, have a full-time job while attending school, or are raising children.

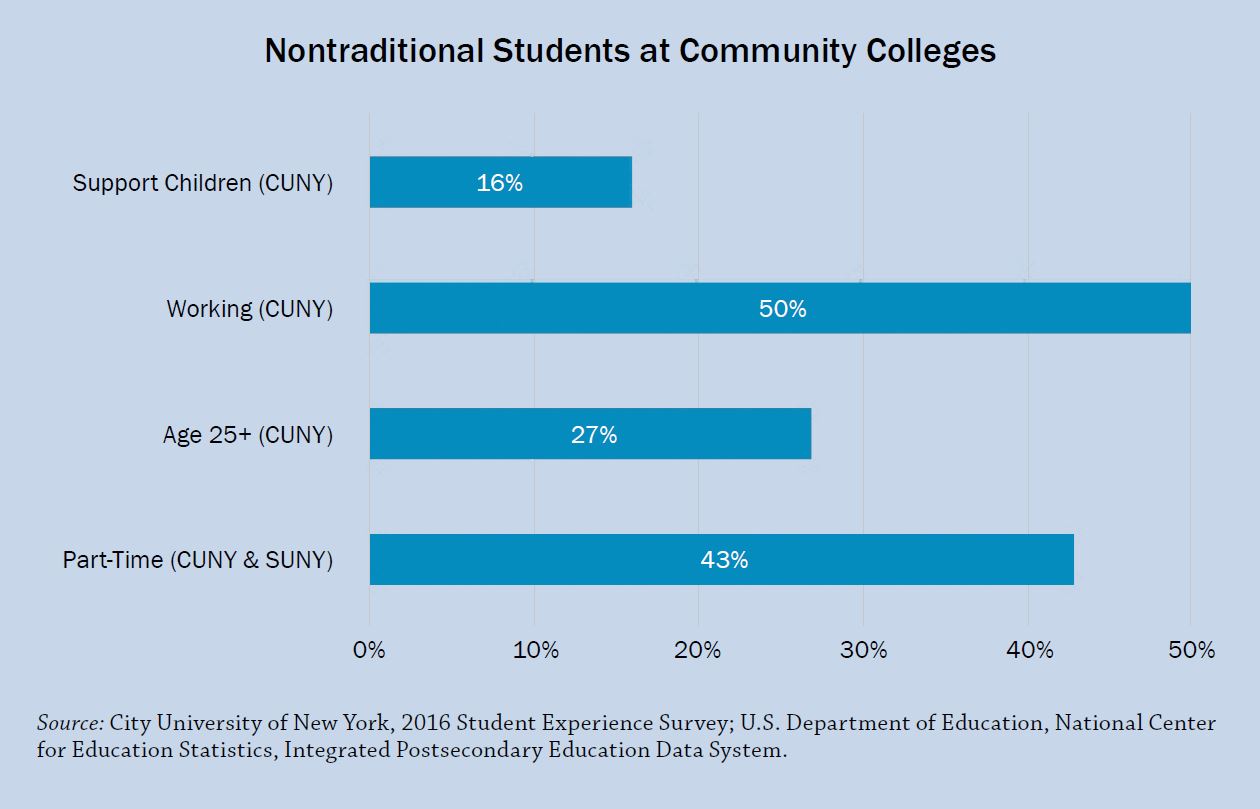

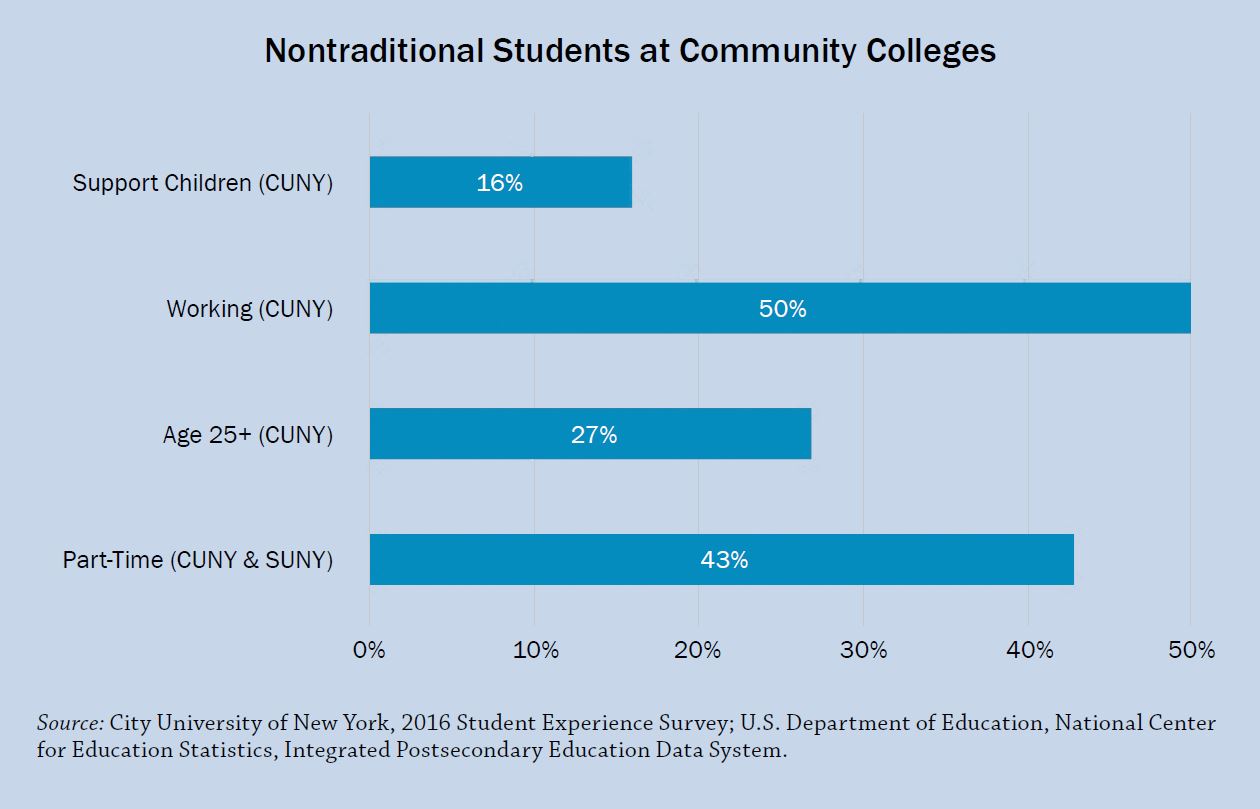

In New York, part-time students comprise 43 percent of all those enrolled in public community colleges statewide—an increase from 32 percent in 1980. Overall, 139,501 students are enrolled on a part-time basis at community colleges operated by the State University of New York (SUNY) or the City University of New York (CUNY). Part-time students outnumber full-timers at 13 of the state’s 37 public community colleges, including Onondaga Community College, Orange County Community College, Schenectady Community College, and Dutchess County Community College.

In New York City, 27 percent of community college students are age 25 and older; half have a paying job, with 52 percent of working students employed more than 20 hours a week; and 16 percent have children whom they are supporting financially.

“The nontraditional is now the traditional,” says Lisette Nieves, a commissioner of the White House Initiative on Educational Excellence for Hispanics and founding partner at Lingo Ventures.

But while part-timers, older students, students with jobs, and students who are caring for children have become the new normal in community colleges from the Bronx to Buffalo, New York has been slow to develop a support system for helping nontraditional students succeed. While the state has one of the most generous tuition assistance programs in the country, few nontraditional students can take advantage of it. Although New York is home to some of the most innovative programs in the nation to increase graduation rates at community colleges—including the Accelerated Study in Associate Programs (ASAP) initiative at CUNY—the programs are primarily geared toward full-time students. Community colleges and education agencies in other states have experimented with new models to support nontraditional students, but in New York education officials and academic leaders have mainly watched from the sidelines.

The need for new approaches is clear. In today’s economy, community colleges are one of the most important platforms for elevating low-income New Yorkers into the middle class and enabling out-of-work New Yorkers to develop new skills for the new economy. But far too many of the New Yorkers who are enrolling in these institutions are dropping out without a degree—and much of the problem stems from alarmingly low success rates for nontraditional students.

The average four-year graduation rate is 28 percent at SUNY community colleges and 24 percent at the City University of New York (CUNY) , but many of the individuals we interviewed for this report say that the success rate is considerably lower for nontraditional students. Although there is little data on graduation rates for nontraditional students, the six-year graduation rate for part-time students at CUNY community colleges is only 20 percent.

For many nontraditional students, the biggest problem is that the road to graduation takes too long and costs too much. Faced with little money in the bank and a child or family member to care for, college ends up competing with paid work, childcare, family obligations, doctor’s appointments, and a host of other demands. Without the right supports, students end up chipping away at just one or two courses per semester—and the reward of a diploma recedes years into the distance. Too often, nontraditional students use up their lifetime supply of federal and state financial aid and run up student loans, raising the odds that an outside event or crisis will derail them from the path to a degree.

“I was a pretty good student, but I could not do what we’re asking our students to do,” says David Gómez, president of CUNY Hostos Community College. “Support a family, sometimes an extended family including parents and grandparents, support a child, go to school full-time, and somehow figuring out how to pay for all of this in the city of New York.”

Some educators in New York and nationally argue that student success initiatives should be targeted at full-time students. These arguments aren’t without merit. Data suggests that those enrolling on a full-time basis have a higher likelihood of graduating. But while encouraging students to attend full-time undoubtedly makes sense, for countless New Yorkers today the prospect of attending college full-time is a fantasy. The reality is that thousands of poor and working poor New Yorkers with family obligations or paltry savings simply can’t afford to quit their jobs and enroll in classes full-time. In 2016, 71 percent of CUNY’s community college students lived in households with combined incomes under $30,000, up from 62 percent a decade ago. Even though tuition assistance programs help defray the cost of college, low-income students still need to cobble together enough money to pay rent and absorb an array of everyday expenses—from groceries to subway fares. The thousands of community college students who have kids at home face additional costs for everything from day care to diapers.

New York has proven that it can be at the forefront of efforts to improve student success. CUNY’s remarkably successful ASAP initiative—which more than doubles the graduation rate of students who participate compared to the traditional approach—has been heralded by education reformers around the nation. But in a state with nearly 140,000 part-time community college students, it’s glaring how little has been done to support nontraditional students.

By implementing strategies that help more nontraditional students earn a postsecondary degree or credential, New York’s institutions of higher education can provide a path to sustainable employment for millions of under-credentialed New Yorkers. A postsecondary education is now an essential prerequisite for middle-income jobs in New York. Of the 25 fastest-growing occupations in New York State with a median wage of $40,000 or more, 22 require a postsecondary degree or credential. By 2018, an estimated 63 percent of jobs nationwide will require some level of postsecondary education, compared with just 28 percent in 1973. Currently one out of every five New Yorkers works in a job that pays below the level required to keep a family of four out of poverty. And poverty is more prevalent among the least educated families; among working families in New York that earn wages at less than 200 percent of the federal poverty line, more than half lack an adult with any postsecondary education.

Accelerating the completion of postsecondary education for nontraditional students will require the state’s public colleges and other state officials to adopt a set of coordinated interventions and reforms designed specifically to help nontraditional students progress more quickly and balance college with other serious responsibilities. This could include interventions such as block scheduling and year-round scheduling, guided pathways, awarding credits for prior learning, and expanding wraparound services and nonacademic supports. Meanwhile, state legislators should consider reforms to the state’s Tuition Assistance Program (TAP), which effectively bars part-time students from receiving aid.

Nontraditional students are more likely to blend work and school, but postsecondary institutions still treat holding down a job as an ancillary activity—a distraction from the ideal of full-time academic pursuits. “It’s a survival penalty,” says Nieves. “Because you have to work, you are trading off on school. We have a generation of students that really believes both school and work are valuable but we force them to choose one over the other.”

This policy brief—funded by the Working Poor Families Project and based on numerous interviews with community college presidents, education experts, and policymakers—presents a menu of options for New York education officials and community college leaders designed to speed the progress of nontraditional students toward a degree.