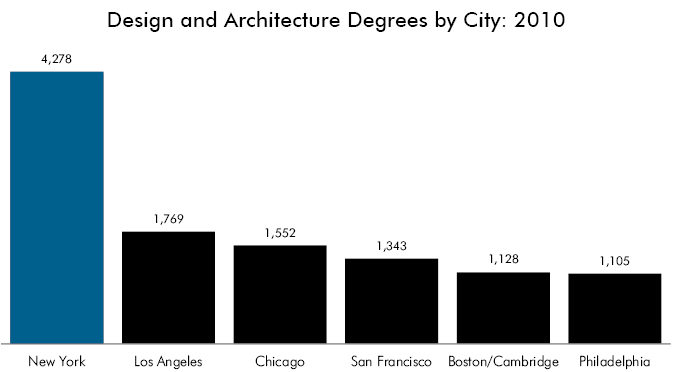

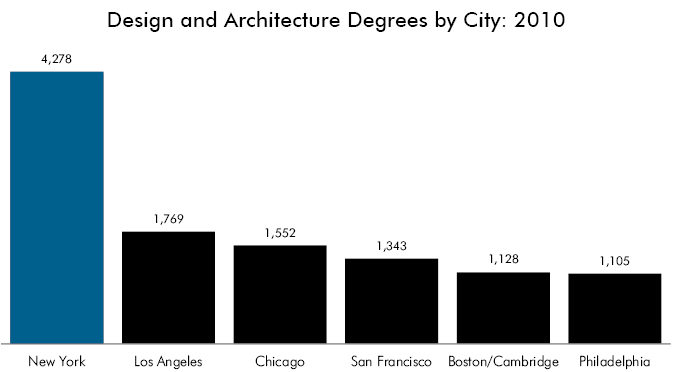

Top schools like Columbia’s GSAPP, Cooper Union, FIT, Parsons, Pratt, and SVA attract talented students from all over the country and globe. In 2010, 4,945 foreign students were enrolled at the city’s seven largest design and architecture schools—a 42 percent increase over 2001. Although Cooper Union and FIT enroll a high number of in-state students too, a majority of students at Columbia, Parsons, Pratt and SVA come from out of state, while 19 percent or more come from abroad. Furthermore, institutional survey data made available to the Center for an Urban Future suggest that a vast majority of students at these schools end up staying in New York City after graduation; many intern at prominent design firms before securing a permanent position or going on to work for themselves.

According to David Rhodes, the longtime president of SVA, the prospect of studying design in New York is extremely attractive to students. “The schools are competitive,” Rhodes says, “but they also have a symbiotic relationship. New York’s dynamic creative community is what all the schools share, and a lot of the prospective students will choose another New York school if they don’t get into their top choice.”

Professional designers clearly see New York’s design schools as critical to New York’s status as a leading design center. This was reflected in the results of a month-long survey we conducted in late 2011 of more than 300 designers, all professional members of trade associations. Among the results of our survey:

-

Of those respondents who indicated that they were a principal or executive of a local firm or business—a group that made up 23 percent of all respondents—80 percent said New York’s design schools were either ‘extremely important’ or ‘important’ to the local economy and 82 percent said they were important local resources for their businesses.

-

81 percent of the principals and executives said they had hired at least one New York City design school graduate in the last five years.

-

43 percent of the principals and executives said they had taught at a local design school and 39 percent said they had themselves attended one of the schools.

Ed Schlossberg, founder of a prominent New York design firm called ESI Design, says that the local schools are an extremely important asset for professional designers, because, among other things, the students they attract make it possible for firms to rapidly evolve with the latest technologies and tools. “If I get a project and it needs three user experience designers or three interface designers,” says Schlossberg, “I have no worry that I’ll be able to find them here. That means I can take the work and expand the business. The schools make that possible.”

Out of 45 full-time designers at Schlossberg’s firm, 14—or 31 percent—graduated from New York City schools, with 8 designers coming out of NYU’s Interactive Telecommunications Program (ITP) alone. Many of the city’s most prestigious fashion and architecture firms also draw heavily from local schools. The figure is even higher at Rockwell Group, a large architecture and design firm. According to company founder David Rockwell, 50 percent of the firm’s professional employees went to New York City design schools. Meanwhile, 30 percent of the designers in Gensler’s New York office studied at local design schools, while 29 percent of the designers at Nanette Lepore, the fashion house, studied locally.

New York’s design schools have also been quietly achieving something that has eluded the city’s applied sciences universities: Year after year, they have been producing graduates who are not only inclined to stay in the city and contribute to one of the world’s most competitive design economies, but risk serious financial and opportunity costs to start their own businesses. To be sure, data on alumni who start their own businesses are extremely hard to come by, since so many of them do so only years after graduating, but several surveys and a wealth of anecdotal information suggest the number for New York is fairly high. For example, a 2009 survey from the Strategic National Arts Alumni Project (SNAAP) found that 19 percent of all Pratt, Parsons and SVA graduates, including non-design graduates like performing arts majors, went on to start their own businesses; the average for all the art schools surveyed by SNAAP was 14 percent. Meanwhile, of the respondents in our own survey who founded their own businesses, 39 percent indicated they were graduates of New York City schools.

Fashion seems to be an especially fertile terrain for these businesses. Our analysis shows that 129 of the 386 members of the CFDA attended either FIT, Parsons or Pratt, and nearly all of them run their own fashion brands and employ other designers. In fact, prominent alums like Calvin Klein, Donna Karan, Marc Jacobs, and Michael Kors all run fashion companies with hundreds of millions, if not billions, in annual sales.

Of course the vast majority of new businesses will never grow that large. But, in design, small firms—even sole-proprietorships—are often major sources of innovation and dynamism. They not only create jobs and encourage innovation by developing new products and services, they are more likely to challenge established business practices and break down industry silos. Pamela Ellsworth, director of FIT’s Global Management Program, believes that New York has been able to reposition itself as one of the leading fashion centers in the world in no small part because it is relatively easy to start a business here. Although it isn’t common, even young designers right out of school have been able to launch their own brands and businesses. For example, in 2002, two young Parsons graduates were able to turn their senior thesis project into a high-end fashion brand—Proenza Schouler—that is now widely considered to be among the most innovative in the business.

Another good example is Situ Studio, a Brooklyn-based architecture firm specializing in high-tech modeling and fabrication services. In 2005, the firm’s four principals, all graduates of Cooper Union’s architecture program, decided against apprenticeships at major New York offices so that they could continue their research into highly technical, computer-controlled fabrication technologies. Whizzes on computers, the four young designers were able to parlay their skills into important consulting contracts with major firms like Kohn Pederson Fox and are now in high demand among not only architects but interaction designers and anyone else looking to bridge the gap between digital modeling and digital fabrication. “Recently, we’ve been asked to work on digital fossil reconstruction for an archeologist at Princeton,” says co-founder Brad Samuels.

Designers and architects have long been willing to forgo traditional career paths in order to start their own ventures, but as the whole industry grows and more small firms get work on major projects, often in collaboration with other small firms, there has been an undeniable trend toward even more entrepreneurialism. Instead of joining established organizations, young designers are increasingly opening their own studios and competing for their own contracts. A number of them have been able to raise hundreds of thousands of dollars on Kickstarter in order to develop products they dreamed up in grad school—hanging window gardens, for example, which recently raised over $250,000 on Kickstarter, or an iPad stylus, which raised $134,000. One of Kickstarter’s founders recently told the New York Times that over half of the site’s blockbuster projects—those attracting $100,000 or more in investments—are design related.

One big factor contributing to this entrepreneurial impulse in design are the students themselves and the entrepreneurial values that they’re beginning to pick up from professionals. For example, Vishaan Chakrabarti, an architect and professor of real estate development at GSAPP, says that “it is no longer a badge of honor among students to be stupid about money.” Students want to learn everything there is to know about realizing a project, Chakrabarti says, and not just the traditional “design” elements such as a project’s look and functionality. However, undoubtedly, design schools are playing an important role in this cultural transformation as well, especially in New York where there is so much professional involvement in the pedagogical process.

For example, while still in school, students are learning to turn their attention to a much wider array of subjects than is traditional in a design education, so not just products, books or buildings, though all of those are still important, but customer service and supply chain systems, food delivery infrastructure, and zoning practices. Furthermore, at all the major schools, design students are learning how to identify problems along the entire development process, from the inception of an idea to its reception as a physical, marketable object—and then they learn how to do rapid prototyping and testing. “They’re encouraged to actually build things,” says Red Burns of her students in NYU’s ITP program, “and to not be afraid or embarrassed if they fail.” One grad student in the Designer as Author program at SVA developed an entirely new prescription drug bottle and labeling system—designed to reduce confusion among older, same-household users—and the market research the student did was so convincing the whole product line was subsequently picked up by Target.

Many of those we interviewed believe that design—and the city’s design schools—will play an even more important role in New York’s economic future. One reason for this is that design clearly plays to New York’s strength as a creative center. Additionally, major companies in technology, manufacturing, health care and other leading industries are increasingly looking to designers to help them solve challenges and come up with innovative solutions. As one example, New York-based Internet companies such as Foursquare, Tumblr, Gilt Groupe and Kickstarter have relied on innovative designs to turn already established technologies into entirely new tools and services.

However, while the city’s design and architecture schools are clearly succeeding on a number of fronts, there are still plenty of opportunities to evolve and improve. Most of the schools have not yet fully explored opportunities to integrate programs that teach students basic business and entrepreneurial skills, for example, including drawing up basic business plans and other financial documents. In our survey of New York design professionals, only 12 percent of respondents said that the schools provided significant opportunities to develop these sorts of business and entrepreneurial skills; 43 percent said the schools provide some opportunities; and 44 percent said it was not a major focus.