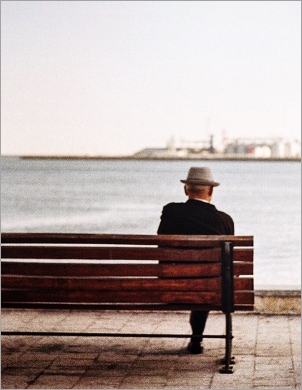

In the months and years ahead, New York City and State policymakers will need to do far more to respond to the dramatic aging of the city’s population. The city is now home to a record 1.6 million New Yorkers age 60 and over—incredibly, 385,000 more than in 2000. This rapid graying of the population is presenting an array of new policy challenges and opportunities—from an alarming rise in poverty and social isolation among older adults to a growing corps of older New Yorker eager to get involved as volunteers and mentors. Policymakers have taken some promising steps to meet the needs of New York’s fast-growing older adult population, but the city’s ecosystem of services to support older adults is still sorely lacking. A bigger and bolder approach is needed in the months and years ahead.

In the pages that follow, we set forth what this approach might look like. Our Blueprint for Expanding and Improving Older Adult Services includes more than 60 achievable policy recommendations for meeting the evolving needs of older adults today—in policy areas such as housing, financial security, social isolation, elder abuse, and transportation. It starts with eight priority recommendations that we believe are most needed to strengthen older adult services across all five boroughs.

Priority Recommendations

1. Double city funding for older adult services. New York City needs a bold new investment in older adult services to meet the growing needs of the largest population of older adults in the city’s history. Mayor de Blasio and the City Council should provide new funding for several city agencies—from the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) to the Department of Housing Preservation & Development (HPD)—to expand or develop programs for older adults. But they should start by doubling funding for the Department for the Aging (DFTA). The agency has primary responsibility for funding older adult services across the five boroughs, but with one of the smallest budgets of any agency DFTA has long lacked the resources to support innovative new programs and scale up current initiatives to meet surging demand. Doubling DFTA’s budget, from approximately $400 million today to $800 million by 2021, will enable the agency to sustain and grow critical support services that are at or over capacity—from home delivered meals and digital literacy programs to NORCs. But at least half of the increased funding for DFTA should be dedicated to supporting innovative programming and experimenting with new initiatives that address social isolation, support the caregiving workforce, develop intergenerational programs, and much more.

2. Create a new office in City Hall to ensure all city agencies integrate older adults into key planning and policy decisions. While greater investment in DFTA is essential to help meet the needs of the city’s growing older adult population, nearly every city agency has a key role to play in supporting older adults—including the agencies overseeing housing, health, transportation, corrections, parks, and hospitals. Up until now, however, few of these agencies are systematically integrating the needs of older New Yorkers into their decision making. It’s unlikely this will change without the backing of the mayor. As such, the mayor should create a new office in City Hall charged with focusing every city agency on age-friendly strategies and helping different agencies pilot new evidence-based initiatives to support improved outcomes in aging. This new mayoral office—perhaps called the Mayor’s Office of Healthy Aging—would be modeled after the Mayor’s Office for Economic Opportunity, a mayoral-level office created during the Bloomberg administration that achieved success in focusing every city agency on strategies to combat poverty. There are other models for ensuring interagency coordination that are worth considering—including an initiative now on the drawing board in which DFTA would establish an Aging Cabinet, whereby high-ranking officials from each city agency would come together regularly to plan around issues affecting older adults. But we believe that a mayoral office based out of City Hall would ultimately have more clout and greater success in getting city agencies on board. In addition, the City Council should pass legislation mandating that each city agency audit its older adult services and develop a Healthy Aging Plan—assessing the current reach and effectiveness of programs serving older New Yorkers and planning for expanded and improved services.

3. Encourage innovation in older adult services by reforming counterproductive procurement rules and incentivizing new approaches. Although New York City benefits from many standout programs and services for older adults, too many of the programs funded by the city do not adequately address what older New Yorkers want and need today. Changing this needs to be a key a priority at DFTA, which for too long has overseen a procurement system that has discouraged service providers from experimenting with new models and approaches. DFTA must commit to wholesale procurement reforms that incentivize innovation and enable city dollars to be used more flexibly. This means ensuring that the next generation of contracts with providers don’t mainly measure success by the number of meals delivered, but instead reward programs that respond to the needs of different communities and deliver high-quality services—including programs run by settlement houses, libraries, and other organizations that have long struggled to access DFTA funds because they don’t serve meals. DFTA should dedicate half of the increased funding it receives in the next five years to supporting innovative new approaches, piloting best practices that have worked elsewhere, and replicating New York-based programs that have proven effective on a small scale. In particular, the agency should encourage and support an expansion of senior centers that are open in the evenings and on weekends, the development of multigenerational and intergenerational programs, and the creation of partnerships between provider organizations. The agency might also consider developing Age-Friendly Challenge Grants, designed to incentivize partnerships between nonprofit organizations or among nonprofits and city agencies in order to tackle growing and unmet needs in the city’s aging population.

4. Launch a major new initiative to reduce poverty among older New Yorkers. With more than 330,000 older New Yorkers living below the poverty line, and many more struggling with financial insecurity, city policymakers need to respond. The mayor and the City Council should launch a comprehensive, multi-agency initiative to reduce poverty among older New Yorkers and help older adults become more financially secure as they age and live longer. The plan should include specific actions to support older immigrants, which have disproportionately higher rates of poverty.

5. Undertake a citywide campaign to enroll older New Yorkers in benefits programs for which they are eligible. To address the alarming rise in older adult poverty, city officials should make sure that a lot more of the older New Yorkers who are eligible for government benefit programs actually take advantage of them. For example, fewer than half of the older adults eligible for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) are receiving nutrition benefits, and just 37 percent of older adults eligible for Senior Citizen Rent Increase Exemption (SCRIE) are enrolled in the program. DFTA should partner with NYC Opportunity, the Human Resources Administration (HRA), and the Department of Finance (DOF) to launch an extensive marketing and outreach campaign designed to call attention to the benefits programs available to older adults and to help them enroll. This campaign should actively partner with libraries, settlement houses, and senior centers to get the word out and provide assistance in filling out applications. In addition to supporting the financial well-being of older adults, increasing access to benefits would also benefit communities since these older adults would likely spend a portion of their monetary savings at local grocery stores, pharmacies, and other businesses. The marketing campaign should raise awareness about the meals and other services provided for free at senior centers in communities around the city. Many older New Yorkers do not know about these services, and DFTA does not provide senior centers with any funding for marketing.

6. Ensure more of the city’s older adult services reflect the diverse needs of today’s older New Yorkers. Although the City Council and DFTA have taken important steps to ensure that city services are serving today’s highly diverse older adult population, there are still significant gaps in the reach and effectiveness of the city’s programs—both in meeting the needs of older immigrants and in serving older New Yorkers who are at different points on the age spectrum. DFTA’s next senior services RFP should require all applicants to more clearly demonstrate how they will ensure that their services are accessible to the immigrant populations in their catchment areas, and senior services contracts should also give providers more flexibility to partner with organizations with the cultural and linguistic competencies to serve immigrant populations. DFTA should also pilot new programs that serve older adults at different points on the aging spectrum, including many more services that appeal to the 1.1 million “younger” older adults aged 60 to 75, many of whom aren’t being well served by senior centers, as well as new programs for the rising number of New Yorkers over 85, many of whom are frail or homebound.

7. Eliminate counterproductive rules and regulations that negatively impact older adult services. New York needs to eliminate many of the confounding rules and regulations that exist across city government which limit the effectiveness of key older adult programs, inhibit innovation, and cause service providers to waste time and resources that otherwise could be devoted to service delivery. The City Council should fund an independent auditor to survey older adult service providers and identify rules, regulations, and processes which are unnecessary, duplicative, or counterproductive. The Council should publish the results and then push DFTA to eliminate or modify the most problematic rules and regulations.

8. The next mayor should come into office with a bold plan to boost support for older New Yorkers. Although there is much that the de Blasio administration can do in its final two years, the next mayor should make healthy aging a top priority and develop a detailed, multi-agency plan to expand services for older adults and better prepare New York for its aging population.

Issue-Specific Recommendations

Housing

9. Make senior housing a centerpiece of the next mayor’s housing development strategy. Mayor de Blasio admirably set ambitious goals to expand the creation of affordable housing, but housing for seniors accounted for just 10 percent of the new units created. The next mayor should make senior housing a signature part of their housing strategy. We believe an ambitious plan to incentivize and build 30,000 new units of affordable senior housing by 2026 is needed given the enormous affordability challenges facing older New Yorkers.

10. Help older New Yorkers age in place by expanding NORCs. City policymakers should take steps to expand the Naturally Occurring Retirement Community (NORC) initiative, which brings vital medical and socialization services to areas with high concentrations of older adults. Many communities across the five boroughs meet the population requirements for a NORC, but have not yet been designated as such. And existing NORCs across the city are severely underfunded, with many struggling just to keep a nurse on-site for the mandated 17 hours a week.

11. Boost the number of older New Yorkers who claim SCRIE benefits. A large percentage of the older adults who are eligible for SCRIE do not currently claim the benefit. The city should develop a comprehensive marketing campaign for SCRIE, targeting senior centers, libraries, buses, medical facilities, and other places where older adults are likely to be reached.

12. Expand innovative models like the shared housing program and the basement pilot program. The city should greatly expand shared housing programs, starting with the city’s current partnership between The New York Foundation for Senior Citizens and DFTA, which connects older adults who have extra bedrooms they could rent with vetted roommates who agree to pay low rents in exchange for helping their older roommates with shopping and other daily needs. It should expand the Basement Apartment Conversion Pilot Program, which provides eligible low-to middle-income homeowners in East New York and Cypress Hills with low or no-interest loans to convert their basements into safe and legal apartments. If the pilot is successful, this program should be scaled up quickly into other communities with aging populations and a concentration of one-to three-family homes.

13. Use data analytics to identify older adults at risk of eviction and provide services. Many older adults at risk of losing their homes will not reach out for help until it’s too late. HPD should partner with NYC DOF to use available housing data to develop an early-warning program to identify households of older adults who are at risk of being evicted. These households should receive targeted educational materials to make them aware of the services that may be able to help them.

14. Allow older adults to apply for an affordable housing waiting list at age 50. Waiting lists for affordable senior housing can be more than a decade long, yet New Yorkers cannot apply for SCRIE or put themselves on a waiting list until age 60. New York should allow older adults to join affordable housing waiting lists starting at age 50, so that more New Yorkers can gain access to affordable housing before they experience a housing crisis.

15. Increase funding for the DFTA Home Repair Program. The city should boost funding for DFTA’s home repair programs, which help older adults find someone to do minor installations and repairs in their homes such as changing a lightbulb in a ceiling fixture or fixing a knob on a stove. DFTA currently funds just five programs in the city.

16. Advocate in Washington for the reinstatement of the LEGACY Act to permit dependents of older adults to live in Section 202 housing. Many older adults take care of grandchildren full-time, yet Section 202 public senior housing does not permit people under the age of 19 to reside in the units, even if the householder is of qualifying age. Congress appropriated funding to support older adults raising grandchildren under the Living Equitably—Grandparents Aiding Children and Youth (LEGACY) Act in 2003 as part of the American Dream Downpayment Act. Minimal funding was allocated for a demonstration project that resulted in a few Section 202 buildings in Chicago and Tennessee allowing grandchildren to live with their resident grandparents. Yet funding has never been expanded. New York’s Congressional delegation should advocate for a revival of this program and push for New York to be included in any new pilot projects.

17. Develop specialized services for older homeless people. The number of adults age 65 and older in the shelter system has tripled in the last seven years, and older homeless adults face unique challenges in navigating the shelter system. The city’s Department of Homeless Services should take steps to ensure that all city-funded shelters are accessible to people with mobility impairments and examine other rules and regulations that create burdens for older New Yorkers. DHS should also consider opening a second shelter specifically designed for older adults.

18. Increase funding to serve older adults without children through HomeBase. HomeBase is a program administered by HRA that helps low-income families and individuals prevent eviction that can lead to homelessness. Yet most of the funding comes from the federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program, which targets families with children. Single individuals without dependents—including many older adults—are served by a much smaller pot of money from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) called the Emergency Solutions Grant. Homeless service providers say the low level of funding means that they must turn away many single individuals and couples without dependents. The city should advocate in Washington for increased funding through the Emergency Solutions Grant and find local sources of funding to help older people without dependents at risk of homelessness.

19. Develop a plan to improve services for the thousand older adults living in NYCHA. NYCHA is home to 78,000 residents ages 60 and above, making it the single largest housing provider for older New Yorkers. But to date, NYCHA has lacked a top-level strategy for meeting the needs of its rapidly aging population and has been extremely slow to develop new programs for older adults. The mayor should work with NYCHA’s leadership to undertake a plan that supports healthy aging in place at NYCHA developments. In particular, NYCHA should install new ramps and elevators to improve accessibility across its buildings; coordinate with social services providers at each development to help older residents affected by interruptions in power, gas, water, or other critical services; establish a more transparent work-order process that sets a target date for when someone will visit a resident’s unit to make repairs; and fund senior centers in NYCHA buildings to make routine, non-structural repairs in the apartments of older residents.

Social Isolation

20. Develop a long-range, multi-agency plan to combat social isolation. The next mayor should bring together several agencies and institutions—including DFTA, DOHMH, the Department of Education (DOE), the Parks Department, the three public library systems, and CUNY—along with senior advocates to develop a long-term plan to address the growing challenge of social isolation.

21. Fund libraries to expand offerings for older New Yorkers. City officials should embrace public libraries as a key part of any effort to tackle social isolation. Libraries are one of the few spaces in New York City where older adults can hang out without spending money. With branches in nearly every community across the five boroughs, they already serve large numbers of older adults, offering a wealth of programs, free space to read and socialize, and a sense of community that spans all ages including thousands of older New Yorkers who don’t want to visit senior centers. But the city’s libraries could be doing even more to serve this population if it had the resources to expand programming tailored to older adults and increase their hours of operation. The city should create a new fund for each of the city’s three library systems to do just this.

22. Expand friendly visiting programs. Friendly visiting programs have proven effective in reaching older adults who are isolated, lonely, and in need of assistance. But just 9 percent of senior centers currently offer this service. DFTA should expand friendly visiting programs across the city. It should also consider partnering with the DOE and CUNY to encourage students to fulfill their community service requirements through friendly visiting.

23. Greatly expand technology-based socialization resources. A handful of local organizations are combating social isolation by using technology to connect older adults virtually as well as in person—from Selfhelp’s Virtual Senior Center to DOROT’s online discussion clubs. Expanding these programs and developing new ones focused on bringing technology into the homes of older adults can help close the digital divide while combating social isolation for those who are homebound or have limited mobility.

24. Launch a new Meal Club program to support social activities. For older adults who are actively seeking to build and maintain their friendships, the city can make it easier to visit a restaurant or café and socialize over a meal. DFTA should develop a program through senior centers and other social services providers where older adults can create Meal Clubs: social groups, supported by a case manager, which receive vouchers redeemable for meals at neighborhood restaurants. This approach would give older adults new opportunities to socialize in their communities—not just at senior centers—and create a new way for older adults to connect with other services, as recommended by the Meal Club’s case manager.

25. Build more adult playgrounds. The city can expand opportunities for socialization through exercise. One opportunity is for the Parks Department to build and maintain more adult playgrounds with body-weight machines, which are particularly well-suited for older adults, and expand programming marketed to older adults.

26. Replicate models where older volunteers serve their neighbors. Bloomingdale Aging in Place, an all-volunteer run organization whose catchment area is in the Upper West Side of Manhattan, is one of a few innovative models in New York designed to identify older adults in need, connect them to services, and combat social isolation. Volunteers, who are themselves older adults, accompany their frailer neighbors to medical appointments or grocery shopping, and help troubleshoot problems with technology and other things. Replicating a model like this citywide would engage more older adults as volunteers while helping stretch meager older adult services dollars.

Caregiving

27. Boost support for family caregivers. The number of relatives providing daily care for frail older adults has exploded in recent years, but the lack of support for these caregivers has created enormous financial challenges for families. Creating a state tax credit for caregivers could reduce some of the burden. A U.S. Senate bill supported by AARP would provide up to a $3,000 tax credit for caregivers. New York State should consider a similar credit.

28. Triple funding for New York State’s EISEP program and expand eligibility. Governor Cuomo and the Legislature should greatly expand funding for the state’s Expanded In-Home Services for the Elderly (EISEP) program, which pays the full cost of home care for single people earning up to $18,732 and a percentage of the cost for single individuals earning up to $31,224. The program is valuable, but way too small in scope. With paid home health care costing upwards of $4,000 per month in New York City, the challenge of affording care in the home is not limited to low income people. At current rates, even a household earning $100,000 a year would be spending half their income on home care. In 2018, just 3,600 older New York City residents were served by the program.

29. Develop a statewide plan to attract, train, and retain more people to the caregiving workforce. The city is facing an imminent shortage of home care workers and supportive services, threatening the health, safety, and well-being of older New Yorkers and their families. In response, the state and city should invest more in training home health aides, create new career ladder programs that help health aides and other frontline service workers learn new skills and advance in their careers, and improve the quality of home care jobs by increasing pay rates for the older adult services workforce.

Healthcare Service Delivery

30. Build a comprehensive patient discharge planning system that includes community-based social services. New York State law requires hospitals to create a discharge plan that often includes arrangements for home care by family or paid home health aides, or admission to a rehabilitation center. But community-based social services providers are too rarely part of the planning process, even though they offer critical rehabilitation, health maintenance, and prevention services like nutritionally balanced home-delivered meals, socialization services, and wellness classes. In cases where discharge planners do refer a patient to social services providers, patients are often dumped on the organization with little information about what the patients’ needs are. The state Department of Health (DOH) and Office for the Aging (NYSOFA) should coordinate with NYC Health + Hospitals and DFTA to support the inclusion of social services agencies in Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) reimbursement plans. The state can help by increasing incentives for managed long-term care organizations (MLTC) to partner with social services organizations. In particular, MLTC can use their legal resources to create reimbursement schemes that can allow socials services agencies to participate in care for older Medicaid patients. The state DOH and NYSOFA should also establish guidelines and procedures for sharing information about a patient’s medical condition with a social services agency deputized to participate in post-discharge care. Additionally, the state DOH and NYSOFA should establish a reimbursement scheme for discrete discharge-related services that can benefit social services providers, and hospital discharge planning staff should advise senior centers on the therapeutic meal needs of patients as part of their hospital discharge plan.

31. Develop a comprehensive safety net for people who do not qualify for Medicaid. There are thousands of older New Yorkers whose earnings are above the very low threshold to qualify for Medicaid, yet do not earn enough to pay for the home care and personal care services that Medicaid provides but Medicare does not. To prevent these New Yorkers from falling through the cracks, New York State should create a program that will reimburse qualified medical expenses for New Yorkers who earn up to 200 percent of the poverty line, which is above the current threshold for qualifying for Medicaid.

32. Expand psychotherapy services to homebound and isolated older adults. The New York State DOH previously funded home visits by psychotherapists, but no longer does. This is a crucial problem because use of mental health services declines precipitously after age 60. Today, just three programs citywide provide in-home psychotherapy services. Governor Cuomo and the State Legislature should restore DOH funding for psychotherapy home visits, and city officials should explore opportunities to expand mental health services to homebound and isolated older adults.

33. Build comprehensive wraparound services for APS clients. Adult Protective Services (APS) provides only rudimentary services for older adults in crisis. DFTA and HRA should coordinate to create a multi-disciplinary response team to help older adults in crisis that is centered around a treating the mental health needs of APS clients.

Financial Security

34. Develop new upskilling programs to help older New Yorkers continue working and earning. There is growing financial pressure to earn income later in life, but many older New Yorkers face daunting obstacles to keeping their jobs or finding new ones as they age. One of the key challenges is keeping up with evolving skills needs. New York City should launch a major new initiative to help older adults remain in the workforce, including robust upskilling programs that teach new technology and other job skills, and coaching for lifelong professionals who are seeking to move into consulting or other freelance work. These programs should also include a new initiative aimed at helping older New Yorkers transition into or seek out part-time work, which can help provide a crucial income boost with a more manageable time commitment.

35. Take new steps to combat age discrimination in the workplace. The mayor should direct the New York City Commission on Human Rights (CHR) to expand investigations of age discrimination in the workplace. In 2018, the NYC Commission on Human Rights performed more than 900 discrimination tests as part of its work to combat bias; however, none were focused on identifying age bias. The CHR should integrate age discrimination into its testing program and perform additional analyses of hiring and termination data to uncover incidents of age discrimination. Additionally, the city should launch a campaign to promote the valuable contributions that older adults make in the workplace.

36. Create new programs to support “encore entrepreneurs.” With the older adult population swelling, life spans increasing, and more New Yorkers in need of additional revenue later in life, there is an enormous opportunity to expand the number of older adults who turn to entrepreneurship or self-employment. Doing so would not only boost the city’s economy, but it could help some older adults become more financially secure. Currently, however, hardly any of the city’s small business assistance programs are focused on “encore entrepreneurs”. The city’s Department of Small Business Services and Economic Development Corporation should develop new programs that expose older adults to entrepreneurship and help older adults plan, fund, and launch their business ideas. They should consider creating new start-up competitions for aspiring encore entrepreneurs and establishing an incubator space specifically aimed at aspiring older entrepreneurs.

37. Create a corps of financial ambassadors to help older adults navigate their finances. Fewer than half of older New Yorkers have access to employer-based retirement plans and even fewer have the knowledge and resources to adequately plan for a future where they will be living off their savings. The New York City Department of Consumer Affairs’ Office of Financial Empowerment should partner with DFTA, the Department of Youth and Community Development (DYCD), and other agencies that run community centers, as well as with individual organizations like settlement houses and the Y to place financial ambassadors who can help older adults create personalized plans for retirement.

38. Open financial planning for retirement programs to people as young as 40. The time to start planning for retirement should not be a few years from retirement age. The Retirement Ambassadors program proposed above should be open to New Yorkers as young as 40 in order to allow them to make the necessary adjustments for retirement.

Food and Nutrition

39. Add subsidized dinner and weekend meals for older adults on fixed incomes. Low-income older adults facing severe rent burden, high medical costs, and fixed incomes often forego proper nutrition. For many, a meal at a senior center provides the most reliable nutrition of the day. But with few senior centers offering dinner and weekend meals, many still go hungry or opt for cheaper, unhealthy food, which can worsen chronic conditions like diabetes and hypertension. In contrast, the DOE has after-school and weekend free meal programs for school-age children, recognizing that school lunch is the only substantial meal that many children receive in the day. The city should add dinner service and weekend meals at senior centers where there is demand and partner with other community-based organizations to provide more subsidized meals for older adults.

40. Expand programs modeled on FreshDirect’s EBT Pilot Program, which provides grocery delivery services for older adults on SNAP. Home delivery can be a lifeline for older adults with limited mobility who do not have healthy food options within walking distance of their homes. But many older adults lack affordable, healthy options for home-delivered groceries and meal kits. The city should expand its pilot program with FreshDirect and develop similar programs with other companies that provide home-delivered groceries and meal kits.

41. Replicate Lenox Hill Neighborhood House’s Healthy Eating Program in senior centers across the city. Lenox Hill serves locally sourced, farm-to- table produce in all its meal programs, including its senior center program. The organization also partnered with GrowNYC, the nonprofit that runs the city’s farmer’s markets, to offer a low-cost Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) program to its clients. This program should be replicated across the city, in partnership with local greenmarkets and other CSAs.

42. Raise the reimbursement rate for meals. Meals are one of the fundamental services provided to older New Yorkers through DFTA funding, but low reimbursement rates limit the quality of meals and stymie innovation. DFTA reimburses senior center and home-delivered meals at a rate that is 20 percent below the national average. The disparity is greater for kosher and halal meals, which providers say they serve at a loss, since the reimbursement rate is insufficient to cover the full cost of the meal. DFTA should raise reimbursement rates to match the national average, and increase support for culturally specific food programs.

Volunteers

43. Tap older adults to serve as volunteers. Older New Yorkers represent a largely untapped opportunity to help the city and their communities through volunteering and mentoring. Many offer a wealth of expertise that could be helpful to city school children, college students, aspiring entrepreneurs, nonprofit organizations or city agencies. But while many older adults would like to get involved as volunteers, a number of them find that it is not so easy to make it work. NYC Service should develop a plan to significantly expand volunteering opportunities for older New Yorkers. This might include an ad campaign featuring older New Yorkers that is targeted not just to senior centers, but more broadly to older adults across the five boroughs. Additionally, city agencies that run large social programs, especially DOE and DYCD, should create new programs for older volunteers.

44. Fund senior centers and NORCs to establish paid volunteer coordinator positions. Most senior centers rely on volunteers for a significant share of programming, but few of them have dedicated volunteer coordinators. As a result, centers are only able to take on as many volunteers as staff can manage while juggling their other responsibilities. DFTA should consider funding paid volunteer coordinator positions at senior centers across the city.

Improving Data Systems

45. Create a set of common outcome metrics for older adult services at DFTA and other city agencies. The goal of public investments in senior centers and other service providers is to ensure that older New Yorkers are fed, to prevent them from being lonely, and to maintain their good health for as long as possible. Yet data about older adult service is limited to how many units of a service were rendered: how many meals were served, how many people attended an exercise class, how many people attended a workshop on diabetes management. But there are no metrics that show how many people actually ate their meals, whether the exercise classes are making participants healthier, or whether people who learn to manage their diabetes better require fewer hospitalizations. DFTA and the Mayor’s Office of Operations should convene a citywide panel of experts to decide on measures that matter when it comes to ensuring quality programming for older New Yorkers.

46. Reimburse older adult service providers based on quality outcomes, not units of service. Service providers that contract with DFTA are reimbursed based on the number of units of service (e.g.: meals, workshop participants) they provide, without regard to the quality of those programs. Indeed, our research shows that the quality of programming can vary significantly from one senior center to another, with better resourced senior centers often offering better quality services. Shifting the focus of reimbursement from units of service to quality outcomes would allow DFTA and other agencies that serve older adults to make a better case for greater investment in services if they can prove that there are measurable benefits in the lives of older New Yorkers. In addition, to ensure that providers are rewarded for finding efficiencies while improving outcomes, any cost savings gained through program design changes should be reinvested back in the services themselves.

47. Build an API bridge to streamline data entry and reporting. Service providers we interviewed for this study cited significant burdens posed by the many hours of staff time required to enter duplicate data into DFTA’s two data systems, STARS and PeerPlace, report data for other funders, and enter data into their organization’s own databases. The New York City Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications (DoITT) should work with DFTA to develop an application programming interface (API) bridge that would allow providers to enter data into a single form, which would then feed into the appropriate data systems, eliminating the need for duplicate data entry.

48. Change NYSOFA’s rules to allow providers to abide by HIPAA guidelines for patient confidentiality instead of those of the Older Americans Act (OAA). The OAA has stricter rules around client confidentiality than HIPAA or even banking rules. These stricter rules impede sharing of data between DFTA and provider agencies that would allow them to better understand how their participants are doing. For instance, medical professionals who conduct depression screenings on senior center participants can only share the results directly with DFTA, not with the senior center. NYSOFA’s rules prevent DFTA from sharing the information with providers, even as the same participants engage in additional depression screenings. This presents a missed opportunity to connect older adults with services that can help them.

Ageism

49. Develop workshops for all city and state staff on working with older adults. DFTA and NYSOFA should partner with an organization that specializes in sensitivity training to train the frontline government workers who have responsibility for helping older New Yorkers get access to services. The trainings should help combat ageism and give front-line staff a better sense for how the services they provide may reach older adults differently. Similarly, client-facing social services staff and other appropriate city staffers should be made familiar with the New York Academy of Medicine’s IMAGE map, which contains services ranging from recreation centers to congregate meals.

Accessibility

50. Review of the accessibility of all government buildings and develop a plan to make upgrades. As New York City ages, the city’s inaccessible built environment prevents many older adults from engaging with and accessing the full range of government programs and services. New York should take a cue from St. Louis, which evaluates the accessibility of its government buildings and outdoor spaces though Facility Audits and Walk Audits. Conceived as part of that city’s Age Friendly St. Louis 2017 Municipal Toolkit, facilities audits entail analyzing and rating each building’s location, accessibility features, wayfinding signage, and other elements through surveys that can be administered by municipal staff, officials, or even residents. New York City should follow the lead of St. Louis and conduct a citywide audit over the next three years, including key facilities like public hospitals and emergency rooms; recreation centers and pools; the courts system; waiting areas for public benefits and services; and other city-owned structures.

51. Provide capital funding to modernize many of the city’s senior centers. To boost participation in senior centers, the mayor and City Council should fund minor capital improvements designed to make more of the centers places that are attractive, comfortable, and appealing to older adults.

Transportation

52. More consistently incorporate the needs of older adults into transit planning. With more than one million residents over the age of 65—a growing number of whom face mobility challenges—accessible and reliable public transportation is a huge and increasing need for the city’s aging population. However, scant attention has been paid so far to the ways that the city’s transportation system needs to evolve to better meet the needs of an aging population. To meet the needs of its growing older adult population while improving transit options for everyone, the city, state and the MTA should more consistently consider the needs of older New Yorkers as they make transit and transportation investments, greatly accelerate efforts to make the public transit system fully accessible, expand and improve bus service, and embrace innovation in paratransit.

53. Fully fund NYC Transit’s plans to make subway stations more accessible and improve bus service. Governor Cuomo and the Legislature should fully fund the MTA’s recently released 2020-2024 capital plan, which includes plans to install elevators at 70 subway stations across the city and make important investments to improve bus service. Both investments are long overdue and would help improve mobility options for thousands of older adults.

54. Continue e-hail paratransit program. A large part of the unexpected costs of the e-hail pilot involve people taking more trips per day than they would with Access-a-Ride. Far from being a problem, this is an indicator that people with mobility impairments are getting out of the house more often. This program should continue, and its cost-effectiveness should be judged on the cost per miles traveled, not overall utilization.

55. Add three-wheel bikes to the city’s cycling infrastructure. One unexplored way to provide more transportation options for people with limited mobility would be to add accessible bicycles to the CitiBike fleet. Bike share closes some of the last-mile gaps in subway and bus service, particularly in the boroughs outside of Manhattan. But riding a standard two-wheel bicycle requires a certain amount of physical strength and balance that some older adults may lack. The city can extend the accessibility of the bike-share network by ensuring that at least 5 percent of the bike share stock is comprised of three-wheeled bicycles. This would allow older people and those with some physical limitations to feel more secure balancing on a bicycle. The city of Milwaukee is piloting the nation’s first system of accessible hand-operated bicycles and tricycles in the nation through its nonprofit bike share operator, Bublr.

56. Launch a new search for wheelchair-accessible vehicles. The introduction of the NV-200 taxi, dubbed the Taxi of Tomorrow during the Bloomberg administration, was intended to create a fleet of wheelchair-accessible taxis. But after the vehicle was deemed unpopular, the Taxi and Limousine Commission opted to stop requiring drivers to purchase it. Applying lessons learned from the rollout of the NV-200, the city should launch a new search for wheelchair-accessible vehicles that could supplement the existing taxi fleet or replace current Access-a-Ride vehicles.

57. Integrate real-time elevator outage and entrance closure information into the web-based Trip Planner and the myMTA app. People who need to find an accessible subway route to their destination can check a box that says, “Accessible Trip.” Yet this feature does not consider elevator outages and entrance closures, forcing clients to look those up separately when choosing a route. The MTA should integrate this information to make it easier for riders with mobility impairments to travel across the city.

58. Improve lighting and cleanliness of subway station elevators. Dingy elevators in many New York City subway stations make the commuting experience even more harrowing for people with mobility impairments. Investing in making elevators more attractive by keeping them clean and installing better lighting can help improve users’ experience.

Elder Abuse

59. Empower older adults to protect themselves from elder abuse. As the older adult population grows, the prevalence of elder abuse is on the rise. This includes a growing number of scams that prey on the finances of older adults, as well as frequent incidents in which trusted friends or family members harm or exploit an older adult in their care. One effective model for reducing the incidence of elder abuse is to empower older adults to better protect themselves. For instance, Neighborhood SHOPP, one of the largest older adult service providers in the Bronx, runs a Violence Intervention & Prevention (VIP) Elder Abuse & Crime Victims Assistance Program that focuses on providing older adults with the information they need to recognize signs of abuse, mistreatment, or fraud, and connecting them to programs and services that can help. Similar programs should be expanded through community-based organizations, senior centers, libraries, houses of worship, and other trusted spaces catering to older adults in each borough.

60. Establish early-warning programs in all the city’s emergency departments. The Vulnerable Elder Protection Team (VEPT) at Weill Cornell’s NewYork–Presbyterian Hospital is a highly effective emergency department–based warning system, in which medical professionals are trained to detect the signs of elder abuse and have an investigation team ready at their disposal. Many older adults will have contact with emergency departments at some point, particularly frailer adults who are more vulnerable to elder abuse. But few other emergency rooms are prepared to assess and resolve instances of potential elder abuse. While child abuse detection training is now standard at most of the nation’s emergency departments, a similar system does not exist for vulnerable older adults. VEPT’s best practice model should be expanded to every hospital emergency room in New York City.

61. Crack down on scams that target and victimize older adults. A growing number of scams targeting older New Yorkers are reported every year, leading to millions of dollars in losses. New York State’s attorney general, the Department of Consumer Affairs, and the district attorney’s office in each borough should expand efforts to track, investigate, and prosecute scams that specifically target older adults.

62. Support, expand, and evaluate the PROTECT mental health program for elder abuse victims to serve older adults across cultures. DFTA launched the Providing Options to Elderly Clients Together (PROTECT) program in January 2019 to connect victims of elder abuse with mental health clinicians from Weill Cornell. This initiative is a great start, since many elder abuse victims can benefit from access to mental health services. Yet services are currently only available in English and Spanish. The program model should be expanded to reach and serve elder abuse victims from Asian and African cultures.

New York State

63. Governor Cuomo and the Legislature should increase NYSOFA’s budget to keep pace with the state’s booming older adult population. NYSOFA’s budget has not recovered since the Great Recession, with the state spending 13 percent less per older New Yorker compared to 2009.