For thousands of New York City public high school graduates every year, the most accessible path to a bachelor’s degree—and with it, a major boost to economic mobility—is to enter the City University of New York (CUNY) as a community college student and then transfer to a four-year institution. The value of this pathway is clear: New Yorkers with bachelor’s degrees from CUNY earn a median annual wage of $68,500 after five years, compared to $53,700 for those with associate’s degrees only—and $38,000 for those with just a high school diploma.1

But despite the power of the transfer pathway to help lift low-income young adults into career success and economic security, the large majority of CUNY students who intend to transfer and complete a bachelor’s fall short of doing so. Although eight of every nine new community college students at CUNY intend to transfer and complete at least a bachelor’s degree, only about one in nine does so within six years.2

There are problems at every point in the transfer process. Many who originally intend to springboard from a CUNY community college to a four-year institution never transfer at all. A smaller number are accepted but do not enroll. Others do transfer, but are unable to complete their degrees.

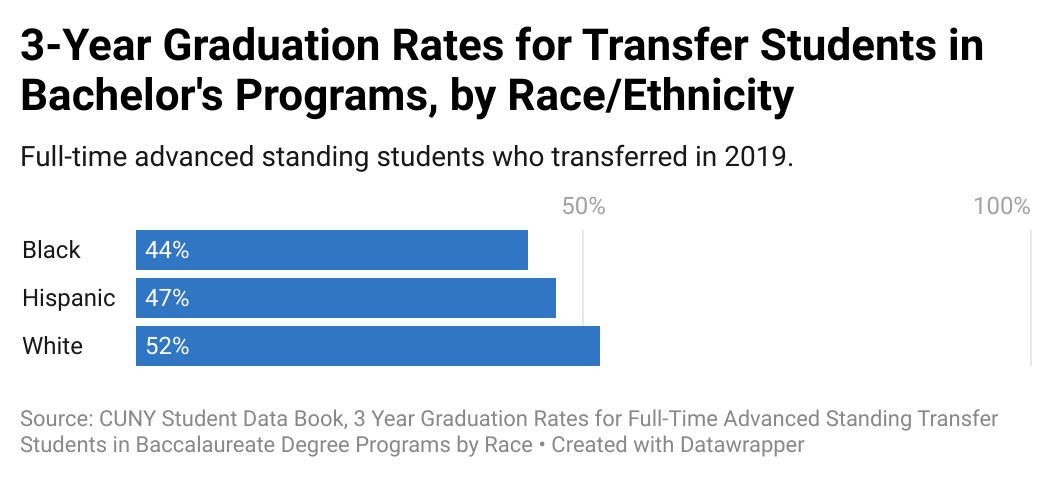

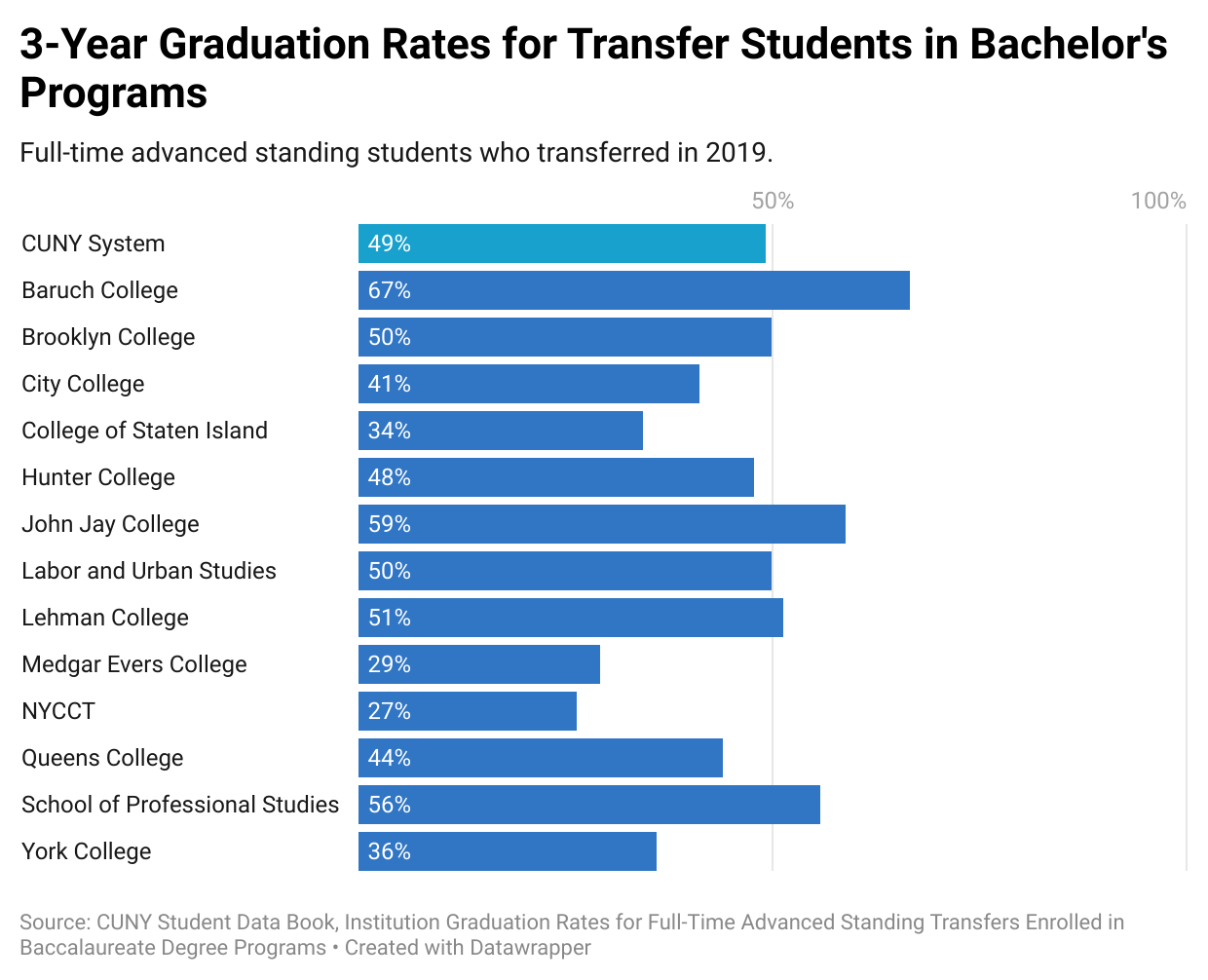

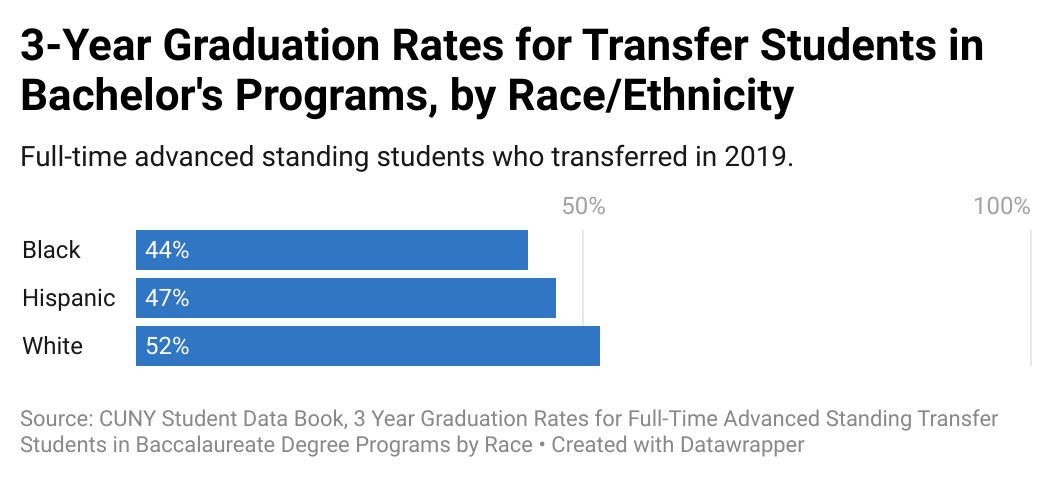

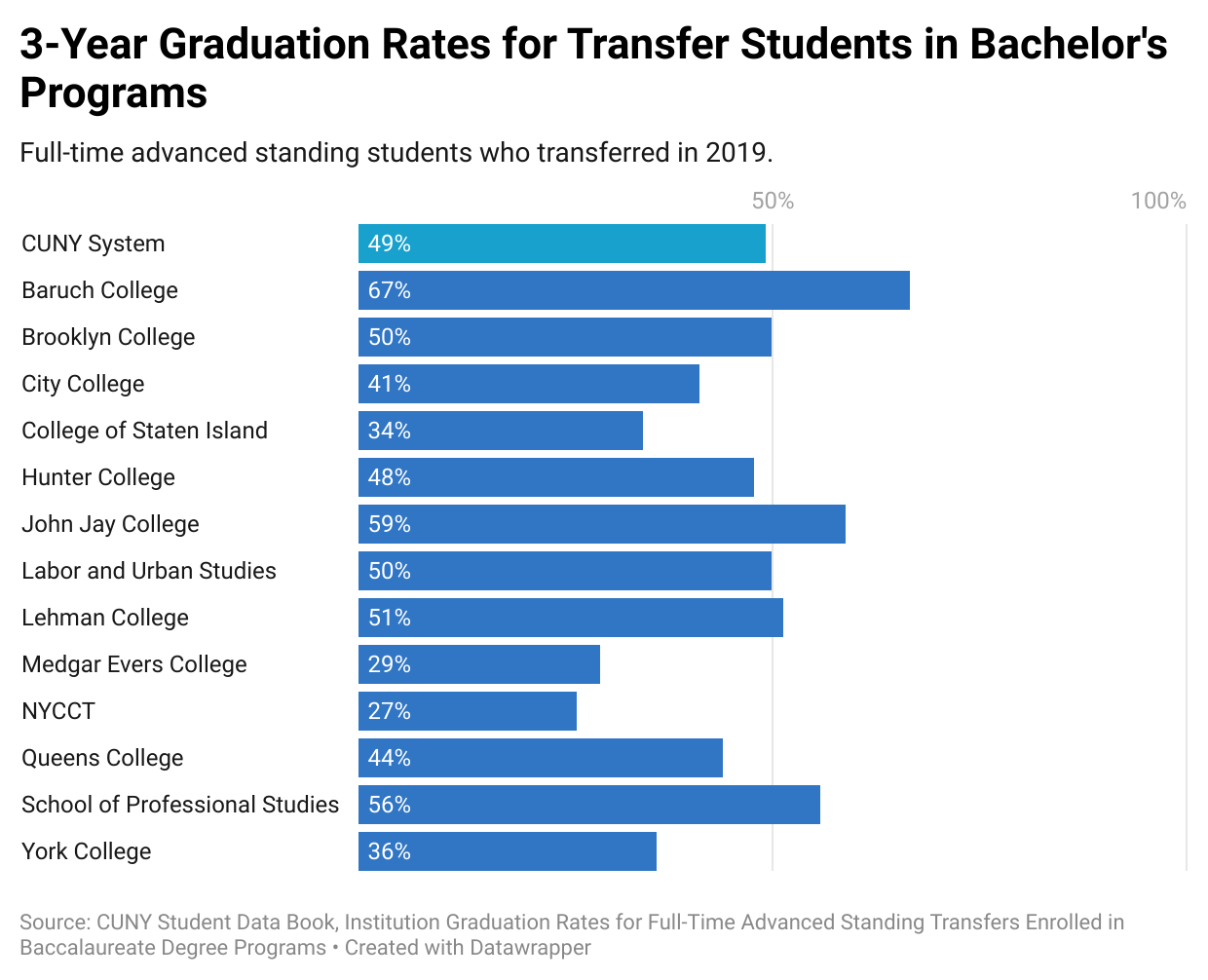

Among the students who do successfully transfer from CUNY community colleges to senior colleges in recent years, fewer than half complete their bachelor’s degrees within three years of enrolling in their destination college. The rates of completion for transfer students are notably lower for Black and Hispanic students: whereas 52.4 percent of white students graduated within three years after transferring, the rates were 44 percent for Black students and 47 percent for Hispanic students. At the same time, transfer performance is wildly uneven across CUNY’s dozen senior colleges. Three-year graduation rates following transfer range from a high of 66.6 percent at Baruch College to 26.5 percent at New York City College of Technology (City Tech). Four CUNY colleges—Baruch, John Jay, Lehman, and the School of Professional Studies—have transfer graduation rates above 50 percent. Four others—Medgar Evers, City Tech, College of Staten Island, and York—see fewer than 40 percent of their transfer students earn bachelor’s degrees within three years.

At the same time, transfer performance is wildly uneven across CUNY’s dozen senior colleges. Three-year graduation rates following transfer range from a high of 66.6 percent at Baruch College to 26.5 percent at New York City College of Technology (City Tech). Four CUNY colleges—Baruch, John Jay, Lehman, and the School of Professional Studies—have transfer graduation rates above 50 percent. Four others—Medgar Evers, City Tech, College of Staten Island, and York—see fewer than 40 percent of their transfer students earn bachelor’s degrees within three years.

To be sure, CUNY is not alone in struggling with transfer outcomes. Community colleges around the country face similar challenges, while often contending with a lack of resources to tackle the problem.

But improvement is possible with a few strategic steps from CUNY and modest investments from city and state leaders. Even gradual progress could help thousands more New Yorkers from low-income communities to earn bachelor’s degrees, putting them on the path to higher-wage jobs and stable, fulfilling careers.

One clear place to start is by helping CUNY scale up a recent initiative that is already achieving striking results. Initially supported by grants from the Heckscher, Petrie, and Ichigo Foundations, the Articulation of Credit Transfer (ACT) project launched in 2020 as a joint effort of CUNY and Ithaka S+R, a policy research nonprofit, with the goal of boosting transfer outcomes by helping students transfer more of their credits from a two-year to a four-year program. ACT has helped develop new tools and practices, including the Transfer Explorer (T-Rex) online tool, and deepened CUNY’s understanding of the challenges that transfer students face.

The impact is already clear: In fall 2019, just 59 percent of students transferring to Lehman College from Hostos Community College could use all of their transfer credits toward their degrees. After implementing process improvements and better advising through the ACT project, the share rose to 72 percent in fall 2021.3

Unfortunately, the grant that made ACT possible only included funding for a three-year demonstration period. And while philanthropic foundations have committed some additional funding to help CUNY continue to enhance tools like T-Rex in the months ahead, there is no guarantee that these transfer improvements will continue to take root and grow across campuses without a new level of support from city and state government.

Beyond scaling up ACT, city and state policymakers would be wise to help CUNY continue to make other investments that have boosted graduation rates for all students. Over the past decade, for example, the university greatly expanded its acclaimed Accelerated Study in Associate’s Programs (ASAP) initiative, which has more than doubled timely graduation rates for students enrolled in associate’s degree programs by ensuring more students benefit from academic advising and peer mentoring and by offering a range of other wraparound supports. CUNY also launched a similar program for students enrolled in four-year colleges, the Accelerate, Complete, Engage (ACE) program.

Yet, there is still considerable room to expand these programs. For instance, while ASAP serves nearly 30 percent of CUNY’s community college students, just 3 percent of CUNY’s senior college students are enrolled in ACE.

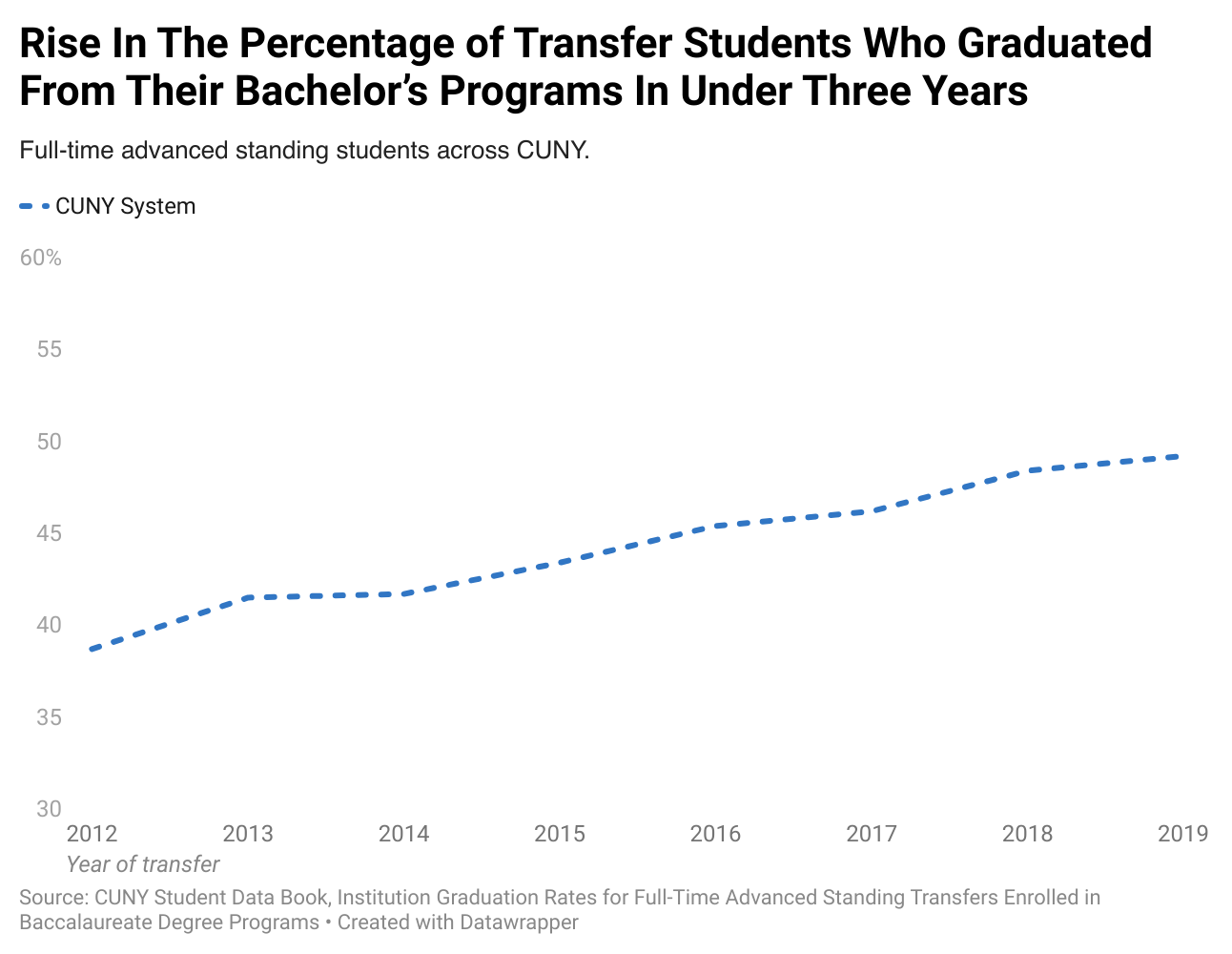

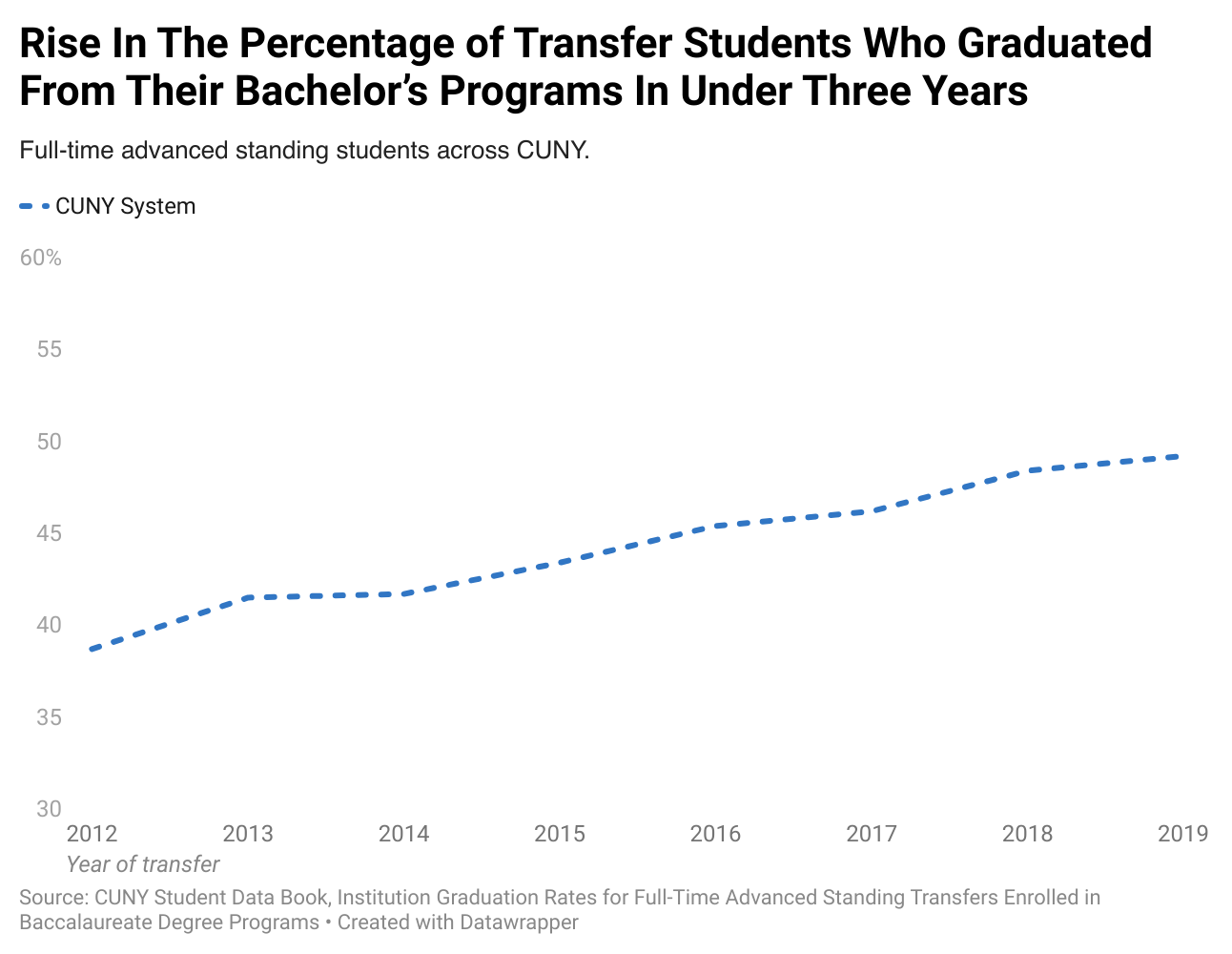

Taken together, the various college success interventions that CUNY has implemented in recent years appear to be working for the transfer student population, too. Indeed, the rate of transfer students graduating within three years of transfer increased from 38.7 percent in 2012 to 49.2 percent in 2019. Every racial group has registered three-year completion rate gains during this period.

Building on this progress will require a new level of attention from city and state leaders and CUNY on addressing pain points in the transfer process. For starters, too often CUNY’s senior colleges will not accept at least some credits earned at the community college level toward the transferring student’s major, which costs students time, money, and lost academic momentum. Many students who do transfer end up with “excess” elective credits—with related costs that financial aid programs will not cover.

Building on this progress will require a new level of attention from city and state leaders and CUNY on addressing pain points in the transfer process. For starters, too often CUNY’s senior colleges will not accept at least some credits earned at the community college level toward the transferring student’s major, which costs students time, money, and lost academic momentum. Many students who do transfer end up with “excess” elective credits—with related costs that financial aid programs will not cover.

Meanwhile, at the campus level, high student-to-advisor ratios—both before and after transfer—mean that students often struggle to access the one-on-one advising that is crucial for navigating the transfer process. Another key factor is what some college administrators call “transfer turmoil”: the jarring cultural adjustment of going from a highly supportive community college environment to a larger and less personalized senior college.

Most students who start at community colleges intend to transfer to a senior college. Indeed, transfer students comprised at least half of 2021-22 graduates at eight of CUNY’s nine senior colleges.4 But despite the popularity of this pathway, experts say that there are very few resources in place to help incoming students understand the transfer experience.

“There’s not enough emphasis on preparing for the transfer process when students are entering college,” says Shalema Henderson, senior director of College Allies & Persistence Partnerships at College Access: Research and Action (CARA), a nonprofit that supports first-generation college students, low-income students, and students of color in college enrollment and persistence. “Given the numbers, it’s kind of surprising that there aren’t more supports built in to do that successfully.”

This will need to change in order for New York to deliver better outcomes for the thousands of New Yorkers who pursue a college degree via the transfer pathway. It will not only require action from within CUNY, but also from Mayor Adams, Governor Hochul, and city and state legislators.

CUNY itself is recognizing the importance of its work: CUNY’s 2023-2030 Strategic Roadmap includes an explicit commitment to supporting transfer students. Internally, CUNY has moved to break through this institutional inertia by reorganizing internally to elevate the importance of transfer. Additionally, the Transfer Explorer team has published campus-level data on transfer students’ outcomes, which is helping college administrators better understand the challenge. But more will need to be done to achieve significant improvements in transfer outcomes across the system.

City and state leaders should consolidate support for improvements in CUNY’s transfer process by launching a new CUNY Transfer Accelerator initiative, which would invest up to $5 million in operationalizing and scaling up the effective practices that are already delivering results. City and state policymakers can also directly improve outcomes by launching a new program—call it CUNY Flex—to provide wraparound supports to nontraditional students, including transfer students, older students, and part-time students. Policymakers should also commit to growing the small-scale but effective CUNY ACE senior college success program, to ensure that transfer students maintain key supports after leaving community college.

At the same time, CUNY will need to take additional steps of its own, such as creating Transfer Success teams at each college to harmonize transfer practices, improving data collection on the transfer student experience, and launching a new Transfer Academy to boost the knowledge of faculty and administrators around transfer policies.

Helping far more of CUNY’s aspiring transfer students to beat the odds and complete a bachelor’s degree is among the most effective steps that policymakers can take to boost economic mobility—and ensure that thousands of New Yorkers from lower-income backgrounds can complete postsecondary education and reap the economic benefits of a bachelor’s degree. This policy brief outlines the challenges that CUNY’s transfer student face, examines why this matters if New York is to succeed in building a more equitable economy, shines a light on several programs and initiatives that are already improving outcomes for thousands of transfer students, and puts forward a handful of achievable recommendations for boosting transfer student success.

II. Transfer at CUNY: An Accessible Pathway to a More Equitable NYC

CUNY is the largest city-based public university in the United States, serving 243,000 students across its 25 colleges and professional schools. More than 80 percent of incoming CUNY freshmen are graduates of New York City public high schools. Fully 85 percent of CUNY students are non-white, more than a third were born outside the United States, and half come from households with incomes below $30,000 per year. Nearly four in five CUNY graduates work full-time in New York state after they graduate, with an even greater majority remaining in New York City.5

CUNY’s seven community colleges offer open admissions, meaning that any student with a high school degree or high school equivalency degree can enroll. That policy helps fuel CUNY’s reputation as a powerful engine of socioeconomic mobility, with many of its campuses recognized nationally for their success in lifting students from low-income backgrounds into the middle class.6

An effective transfer experience is a key component of this economic mobility engine. The idea is that any student can begin their higher education experience in a supportive educational environment, meeting core requirements and adjusting to the world of education beyond high school. Then, they can transition to a second institution where they can complete a four-year degree and get on track for a well-paying career. The transfer pathway is more affordable, too: community college tuition at CUNY for a New York City resident is $2,400 per semester, compared to $3,465 at a CUNY senior college.7

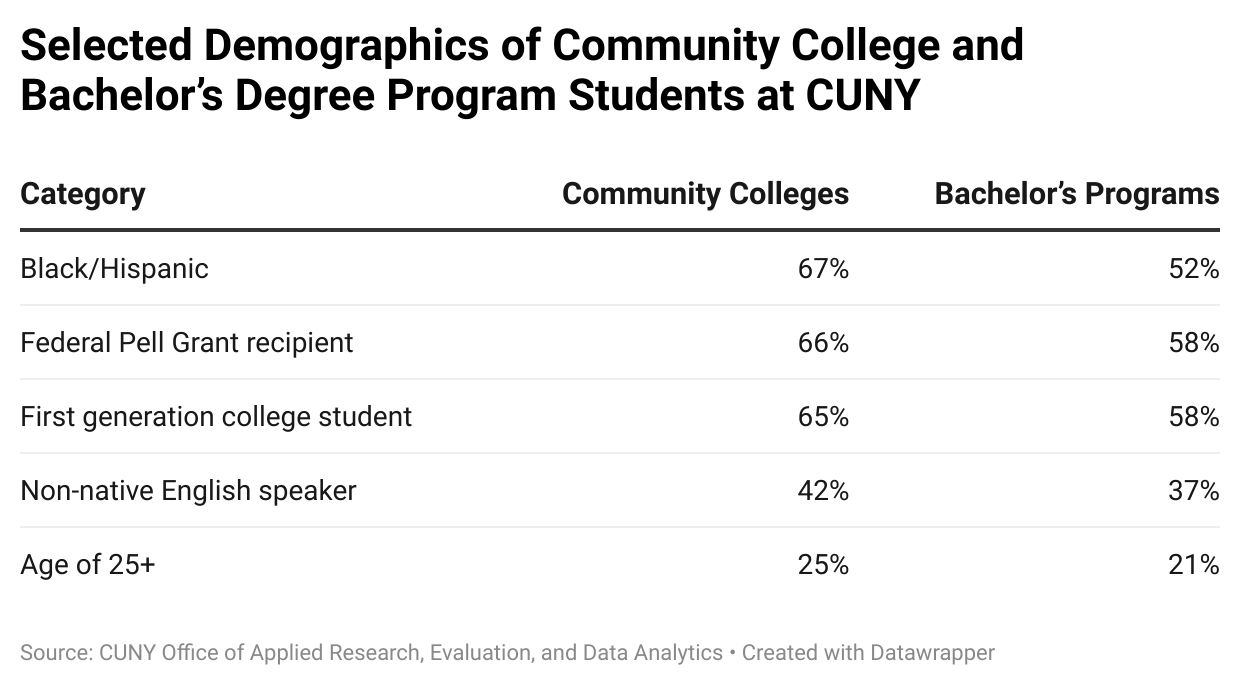

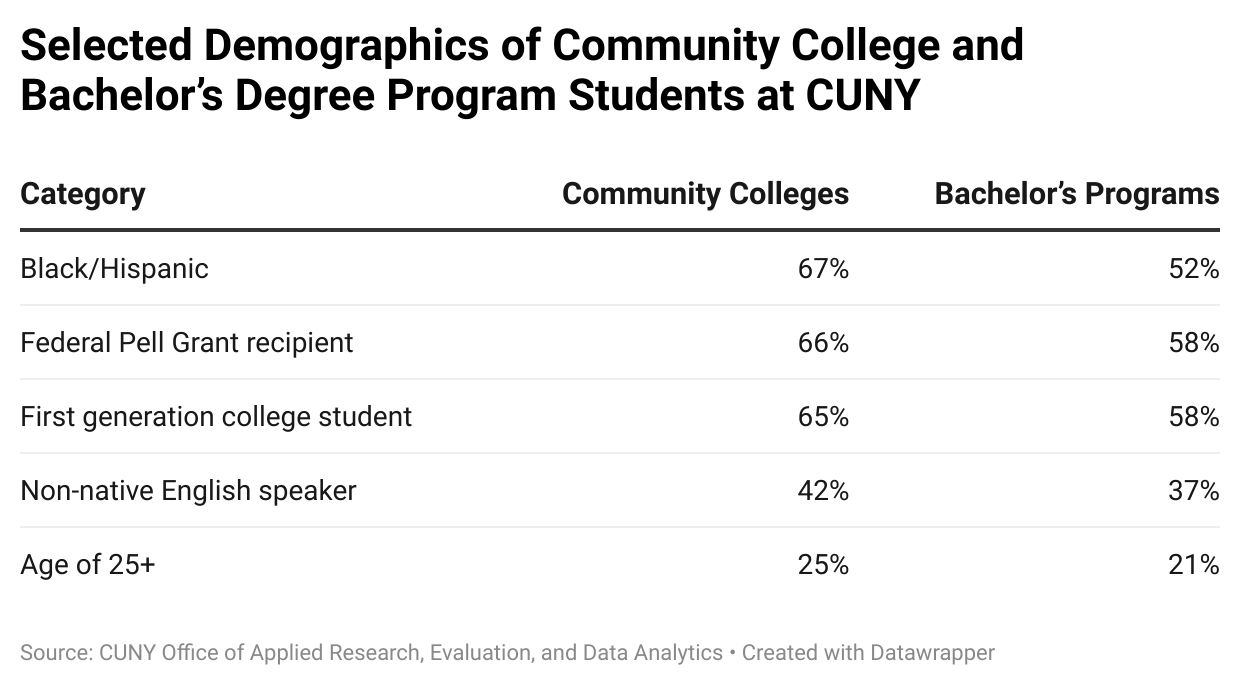

Compared to students who enroll directly into bachelor’s degree programs, community college students face greater risk factors to degree completion, even as their success can confer even greater economic mobility gains. Compared to students in bachelor’s degree programs, community college students are more likely to be Black or Hispanic (67 percent to 52 percent), a recipient of federal Pell grant assistance (66 to 58 percent), a first-generation college student, a non-native speaker of English, and 25 years of age or older.

If New York is to succeed in helping more low-income students of color, first-generation college students, and immigrants to obtain bachelor’s degrees, strengthening the transfer student pathway will be essential. Unfortunately, transfer outcomes reveal striking racial and ethnic gaps, as well as major variations among CUNY colleges. Overall, 49.2 percent of all CUNY students who transferred in 2019 completed a bachelor’s degree within three years. But whereas 52.4 percent of white students graduated within three years after transferring, the rates were just 44 percent for Black students and 47 percent for Hispanic students. Additionally, rates varied across CUNY colleges from a high of 66.6 percent at Baruch College to a low of 26.5 percent at City Tech.

One reason for this variation is that each campus functions with a great deal of autonomy—a reality that plays a key role in shaping transfer policy. “It’s hard to talk about transfer at the campus level, because by its nature it’s inter-institutional,” says Martin Kurzweil, vice-president of educational transformation at Ithaka S+R and a co-lead investigator at CUNY’s Associate’s to Bachelor’s Degrees (CUNY A2B) project, which has led a series of research projects and piloted innovative program models to improve transfer outcomes.

In the absence of prior agreements and credit evaluations, for instance, designated faculty members at each CUNY college usually make their own decisions regarding whether and how to accept credits earned by transfer students at their original institutions. Similarly, administrators are largely left to determine how much of a priority should be placed on transfer students, and how to make relevant investments. This means that when one CUNY college implements an effective tool or strategy to support transfer students, there is no guarantee that other CUNY colleges will take it up. In turn, this helps explain the wide divergence in transfer outcomes at the campus level.

III. Bumps in the Road: The Uneven Transfer Experience at CUNY

CUNY students who aspire to transfer from two-year to four-year programs face a number of challenges that are consistent across the system. While the obstacles begin before students even apply to transfer in the first place, our research suggests that the greatest barrier is often loss of credits that can count toward degree requirements. The next most significant issue is the shock of losing the supports of community college. Other major concerns include the loss of students admitted into bachelor's degree programs who end up not enrolling, and the large share of aspiring transfer students who leave college before earning an associate’s degree or transferring to a four-year college.

Lost credits, demoralized students

Perhaps the greatest challenge facing aspiring transfer students in the CUNY system is that credits they thought would count toward the major requirements of their four-year degree can suddenly change to elective status upon transfer. CUNY has a policy designed to ensure that all credits transfer, but faculty members at the destination campus have a great deal of discretion in determining how to categorize the transferring credits. If a new college classifies credits that a transferring student believed would count toward their major as elective credits, those credits become effectively useless in making progress toward a degree.

Several recent studies have shown a strong correlation between how many credits a transferring student can apply toward graduation at their new college, and their odds of successfully completing a bachelor’s degree. Nationally, researchers have found that students who have all or almost all of their credits transferred are more than 2.5 times as likely to graduate compared to those who are only able to transfer less than half of their credits; those who transfer between half and 89 percent of their community college credits are 74 percent more likely to graduate compared to students who transfer less than half of their credits.8 A 2017 report from the federal General Accounting Office found that students who transferred lost an estimated 43 percent of their credits in doing so, with an average loss of 13 credits.9

It is unclear how closely figures at CUNY track these national averages, although research suggests that this issue is pervasive. A 2022 study found that 47 percent of CUNY transfer students transferring to a senior college between 2013 and 2021 lost at least some credits they thought might count towards a bachelor’s degree, with an average loss of nearly 11 credits—almost a full semester of work, or nearly $2,400 in tuition.10 But this figure did not capture a key distinction within the data: students can lose credits for a variety of reasons, including their own decisions to change their major. Researchers at CUNY are currently working to better understand the extent of credits effectively lost directly as a result of transfer.

Unfortunately for transferring students, destination colleges have a number of incentives to say no, rather than yes, to accepting credits. Most obviously, accepting credits that a student earned at their original college means that the destination college cannot charge the student for the course they otherwise would be obligated to take. Although CUNY has taken steps to minimize how often this happens, it is perhaps the biggest contributing factor to credit loss among students who successfully transfer.

Particularly in a moment when higher education budgets are under the triple strain of shrinking enrollment, public skepticism about the value of college, and declining support from public spending, colleges have a powerful incentive to maximize their short-term revenue by obligating students to pay tuition to retake courses. But this short-term focus can lead to long-term financial harm. Transfer students whose credits are rejected or categorized as elective face a longer road to credential completion and are more likely to drop out before completing their degrees—depriving the institution of tuition revenues. Worse, this can drive a vicious cycle, with schools incurring reputational damage as inhospitable to transfer students.11

With this in mind, educators and administrators can work to more closely align the curricula and learning goals of community college courses with those established at the four-year colleges, in order to address faculty concerns that a similar subject taught at the community college level might fall short of the rigor required at the senior college. Additionally, university leaders and city and state policymakers can create counterincentives by conditioning financial support to CUNY schools on transfer students’ persistence and completion of degrees. Or similarly, they might condition financial support on degree completion rates for students from low-income backgrounds or populations historically underserved in higher education which would indirectly achieve a similar result. Such measures would have to be sized and structured to balance out the short-term revenue colleges would forego by not requiring students to retake courses.

“Transfer turmoil”

Exacerbating the credit loss challenge is the loss of institutional support that many transfer students experience in moving from community colleges to four-year colleges. For instance, nearly 30 percent of CUNY’s community college students are enrolled in ASAP, which has succeeded in roughly doubling graduation rates compared to non-ASAP students. Students in ASAP benefit from financial resources including tuition waivers, free MetroCards, and textbook assistance, while also receiving personalized advisement and tutoring.

The problem is that these supports largely fall away for students who transfer to a senior college. For instance, CUNY’s similarly supportive Accelerate, Complete, Engage (ACE) program—designed to be like “ASAP for senior college” students—only has sufficient funding to reach about 3 percent of CUNY’s senior college students each semester. As a result, thousands of transfer students end up losing access to the key mix of supports that enabled them to succeed in college in the first place.12

“We call it ‘transfer turmoil,’” says Michael LoPorto, associate director of student success at Brooklyn College. “It’s a feeling of not belonging, feeling adrift. Feeling unsure even where to go.” LoPorto cites the phenomenon of students simply “shutting down” rather than seeking help, and adds that this is particularly concerning at a moment when students are facing a steeper academic challenge. “Most students transfer in their third year, and classes are just more difficult at that point. So you’re coming to a new school, the advising structure is different, you’re more on your own, and then you’re taking Organic Chemistry or Calculus 2. You’re getting hit on both sides.”

At senior CUNY colleges, the student-to-advisor ratio can run as high as 1,500 to 1. “A lot of the colleges lack advising capacity broadly,” observes Cass Conrad, executive director of the Petrie Foundation. (The Petrie Foundation has supported CUNY A2B’s research under the Articulation of Credit Transfer initiative in addition to related initiatives such as the development of proactive advising models such as the Transfer Advisement Coaching approach at Brooklyn College.) “There are just not enough advisors per student,” she adds. “That’s definitely true on the transfer side as well.”

Even CUNY campuses known for their focus on supporting transfer students, such as Lehman College, sometimes fall short. Jeremy Quinones transferred from Hostos Community College to Lehman for the fall 2020 semester during the COVID-19 pandemic and was barely able to engage with school staff before classes started.

“I didn’t hear back from Lehman until either the week before or the week of classes starting,” says Quinones, who is still working toward completing his bachelor’s at Lehman. “I should have had my schedule and met with an advisor way before that. When I finally did, it was a 30-minute Zoom meeting, and she just pulled my records and built a schedule based on what she saw. I didn’t really feel like she had much patience. I got maybe one question in, and that same day I had to go enroll in courses.”

Another factor exacerbating the transfer shock challenge is a reliance on aging data systems that inhibit communication between colleges. “So much of what we need is related to technology,” says CUNY Associate Vice Chancellor for academic effectiveness and innovation, Alicia Alvero, who is leading the systemic effort to improve transfer outcomes. Because each campus uses its own data system, she explains, “When a student transfers from a community college to a senior college, the advisor at the senior college can’t see anything about their previous experience in CUNY. Not even their attendance records. Native students who start from freshman year have tons of data that inform predictive analytics, and that advisors can use to customize what supports they provide. For transfer students, they’re starting all over.”

Although CUNY’s community colleges are generally more directly supportive of students than their four-year counterparts, students are still obligated to figure out a lot on their own—from course selection and managing expectations of credit transfer, to navigating available on-campus resources. Student-to-advisor ratios, while significantly lower than those at the senior colleges, still number in the hundreds, and students who are balancing school and work obligations, have limited English proficiency, or are the first members of their families to enroll in college are less likely to seek out advisors. Meanwhile, the highly effective CUNY ASAP program is only available to full-time students, which excludes the more than 31,000 part-time community college students enrolled at CUNY.

Limited knowledge of transfer pathways among students and faculty

Relatively few students enter community college with a detailed plan to take foundational courses, then apply to a specific senior college or a targeted degree program. “If you go into community college with a very clear and informed pathway and stay the course on that and then transfer, you’re fine,” says Lori Chajet, co-director of College Access: Research and Action (CARA). “But the majority of students who go from high school into community college are not going in with such a well-defined pathway.” The less clarity students have around their college goals and the steps needed to access the transfer pathway, the more an unanticipated bill, family issue, or academic challenge can derail their momentum.

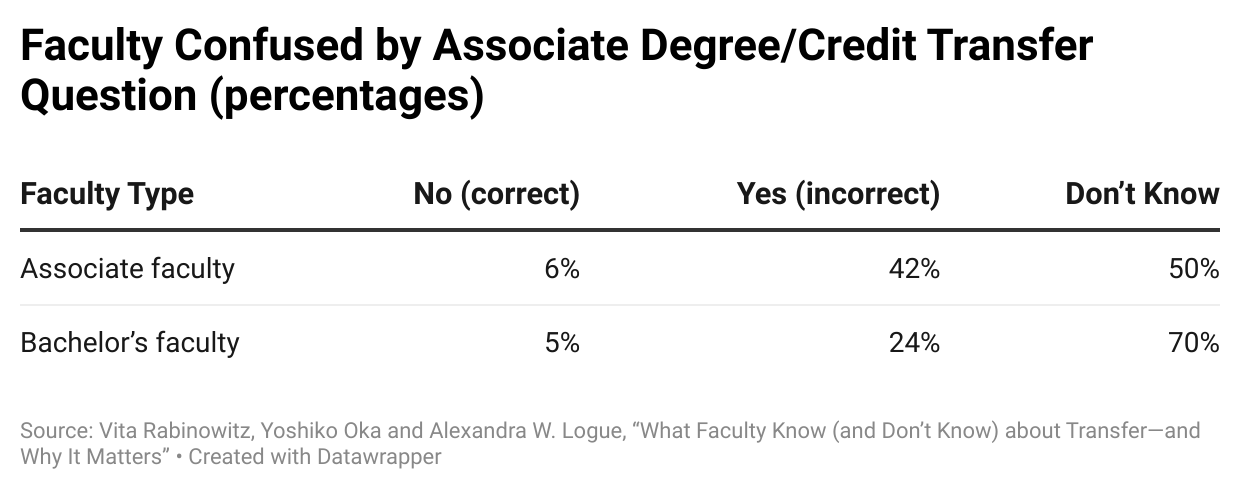

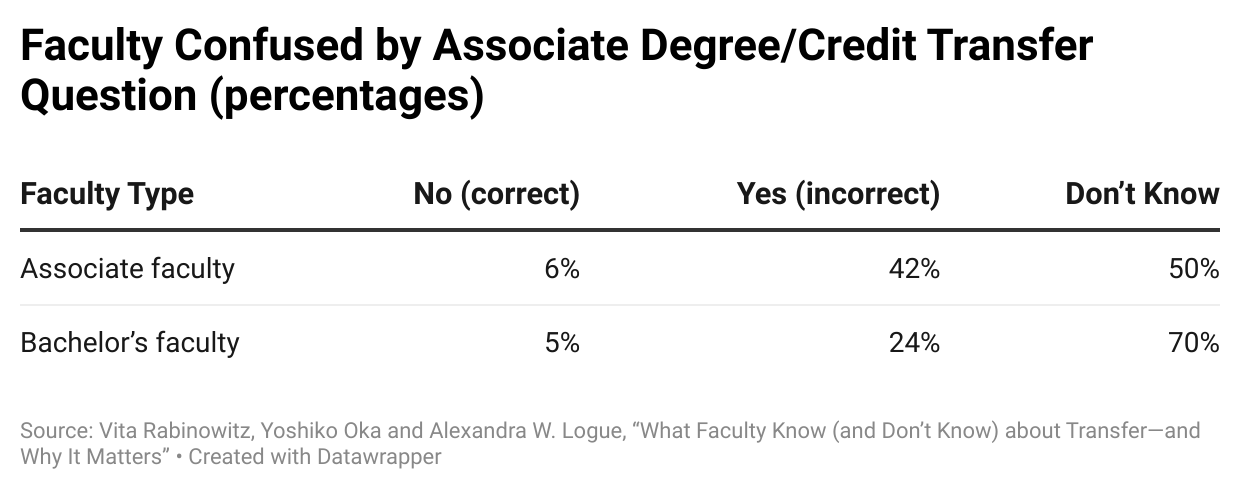

Making matters worse, good advice can be hard to find. Recent surveys of CUNY faculty and students found that both groups are frequently misinformed on issues of transfer policy. For example, faculty were asked whether students who complete an associate’s degree program before transferring have more of their credits count toward a bachelor’s degree than those who don’t complete the associate’s before transferring. The correct answer is “No,” but as Table 2 shows, around 5 percent of faculty members gave that response.13

With overstretched college advising departments offering limited hours and availability, students frequently turn to their professors for advice relating to transfer. A mistaken response such as the one above could convince a student to unnecessarily remain in their associate’s program until completing the degree. In turn, this might lead to them losing time and earning credits that will not count toward requirements for their major, at a cost of thousands of dollars in tuition. These knowledge gaps are likely a significant contributing factor to leakage across the transfer pipeline, from students’ not applying to transfer at all, to credit loss and struggling with academics and general adjustment after enrolling at their destination campus.

“There’s no question faculty don’t know a lot about transfer,” says Alexandra Logue, lead investigator at CUNY A2B. But she stresses that faculty, focused as they are on teaching courses and conducting research within their college, cannot address these challenges on their own. “By its nature, transfer has to do with more than one college. How is a faculty member going to know about these issues on their own, unless somebody tells them?”

The same survey found that CUNY staff and faculty are only “somewhat confident” in their understanding of university policies related to transfer, and that most faculty reported rarely or never communicating with other offices at their institution about those policies or related issues.

At Lehman College, advisors have tried to be proactive in closing this knowledge gap. “We’ve done a lot of campaigning with faculty to spotlight transfer more,” says Emily Denham, a pre-transfer advisor at Lehman. “We’ve created two-page worksheets that map out programs—if a student is enrolled in a certain program at a two-year school, page two is what they have left to take at Lehman. It helps faculty see the student holistically as a transfer student.”

CUNY A2B Finds Leaks in the Pipeline

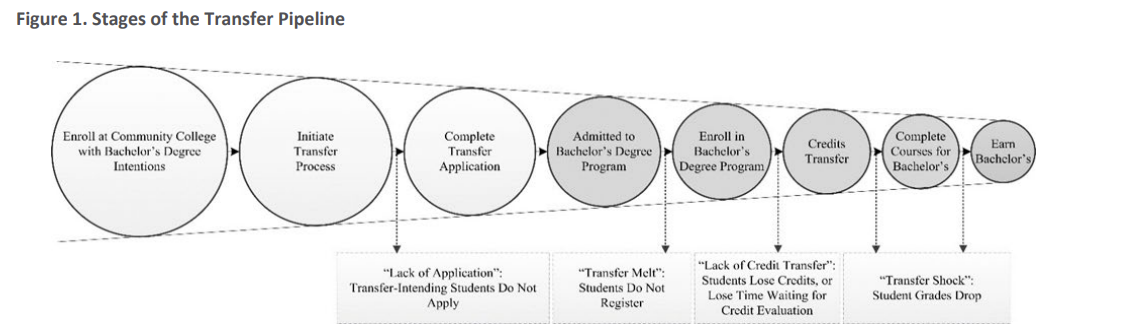

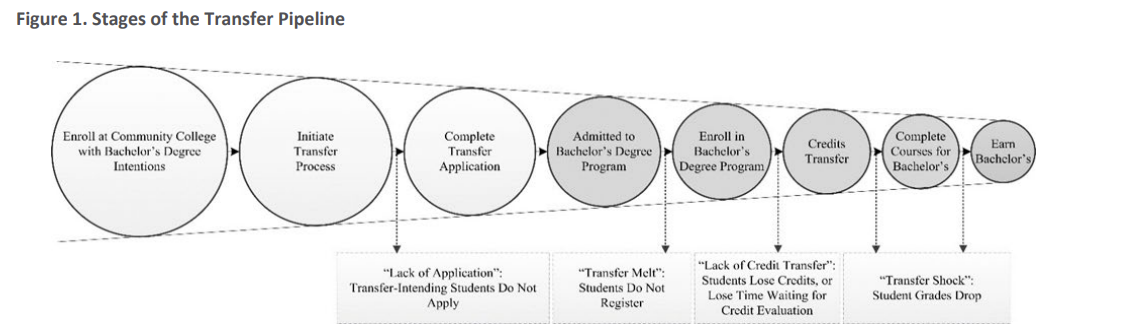

CUNY’s Associate’s to Bachelor’s (CUNY A2B) project has conducted extensive research to understand the typical pitfalls facing community college students looking to transfer into bachelor’s degree programs. A2B researchers identified four major points along the transfer pipeline where students are most likely to fall off track. In sequential order as shown in Figure 1 below, they are:

Not applying to transfer. Between a third and half of students who start community college end up dropping out before earning an associate’s degree or transferring to pursue a bachelor’s.

“Transfer melt.” This term describes students who were admitted into a bachelor’s degree program but did not enroll. In the period CUNY A2B studied, between 21 percent and 39 percent of admitted students did not enroll during the first term after being admitted. While many of them entered the bachelor’s program to which they had been admitted in subsequent terms, 9 percent never did.14

Credit loss. Perhaps the best known challenge facing transfer students, the failure of credits to transfer from the student’s community college in a manner that counts toward their major in a four-year college affects a significant number of CUNY transfer students.

“Transfer shock.” Some students who successfully complete the transfer often find themselves in newly challenging academic circumstances, and their performance suffers as a result. 60 percent of CUNY transfer students see their grade point average fall at their new college, with an average decline of 0.72 points.15 Research from CUNY A2B suggests that nearly 13 percent of CUNY students who transfer drop out within one semester of doing so, and more than 21 percent are no longer enrolled after one year.16 While a number of these students subsequently re-enroll in later semesters, most do not return.

Source: CUNY Transfer Opportunity Project, “Transfer Application and Transfer Melt: Longitudinal Analysis of Students who Start in Associate Programs,” July 2021.

IV. Systematizing Success: Scaling Up Transfer Best Practices at CUNY

For all the difficulties that CUNY and colleges across the country have faced in serving transfer students, there is growing consensus around the mix of policy changes and supports that are effective in boosting their success. Schools and systems that offer clear and actionable information, look to say yes rather than no to credit transfer, and emphasize a welcoming and supportive culture tend to see significantly better outcomes. CUNY has developed a number of highly effective practices in all three of these areas, which should be scaled across the university’s 20 undergraduate colleges.

Transfer Explorer: Bringing transparency to transfer

Perhaps the single highest-profile change of recent years to support transfer students across the CUNY system is the online tool Transfer Explorer, known as T-Rex. Developed as part of the ACT project, the tool includes an estimated 1.6 million “transfer rules” that show how courses at one CUNY campus will be credited at other campuses.

T-Rex performs two vital functions. First, it gives students greater certainty about how their specific courses will translate at other CUNY campuses. For example, a Bronx Community College student who has taken the three-credit course “Bio 19: Food, Sex and Death (Selected Topics in Biology)” would be credited for the three-credit “Biology 1010: Biology for Today’s World” at Brooklyn College, a biology elective credit at Lehman College or Medgar Evers College, a three-credit liberal arts elective at Queens College, and so on.17

“Before T-Rex, you could never really say with confidence that what you see would be what you get,” says Chris Buonocore, director of student success initiatives at Lehman College and a key figure in the development of the tool. “With T-Rex, when you see an equivalency, that’s what you’ll get when you actually transfer. Previously a student would have to know an advisor, or contact someone in admissions.”

The second, related function is that T-Rex provides a new level of transparency regarding how transfer-friendly various campuses’ credit transfer policies actually are—and a lever for pushing campuses to be more generous. “If you have a more specialized psych or business course that one senior college accepts for credit but the other doesn’t, that can help inform the student’s decision about what senior college to go to—it performs a market information function,” explains Alexander Ott, associate dean of academic affairs at Bronx Community College. “It also opens the door for a discussion with the senior college about why its peer accepts a course for transfer and it does not.”

Lehman’s Buonocore notes that since T-Rex launched in May 2020, he has seen several CUNY colleges change credit equivalencies for certain courses from elective to counting toward a major. “We’re changing all these things that previously weren’t helping students to things that will benefit them as they transfer to other CUNY institutions,” he says.

Buonocore and others add that CUNY’s central office has come to champion T-Rex and other digital tools—a notable example of the institution’s leadership pushing campuses toward a unified course of action. One way CUNY has done this is by creating a network of key contacts for T-Rex on every campus, with opportunities for them to ask questions, seek or provide training, and share effective practices.

College advisors and others think that Transfer Explorer could do even more to support student success. “It is a great way for students to figure things out ahead of time,” says Ambrosia Powell, a former transfer student who graduated from Brooklyn College and now works there as a Transfer Advisement Coach supporting students coming to the school from Kingsborough Community College. “I would love to see students using it at their original [pre-transfer] school. It should be part of their advisement, especially for students who are working and have families.”

CUNY ASAP, College Discovery and SEEK: Proactive advising and support

In an ideal world, preparation for transfer would begin in a student’s first semester of community college—if not while they are in high school. Utilizing tools such as T-Rex, advisors could help students build an academic program that would maximize their financial aid resources while minimizing the time they spend in school, which is a key factor that helps increase the likelihood of getting to graduation. This support would continue through and beyond the point of transfer, helping students navigate their destination college and access the support needed to complete their degrees.

While CUNY doesn’t have this kind of system comprehensively, it does offer community college students access to some of the most effective college-success programs in the nation. The best known of these is CUNY ASAP, which provides a range of services from free MetroCards and textbooks to individual and cohort advisement and “block” scheduling that helps students balance school with work and family obligations. ASAP now serves roughly 42 percent of full-time students in associate programs,18and they complete their associate’s degrees at close to double the rate of non-ASAP students.19A counterpart program for students at senior colleges, CUNY ACE (Accelerate, Complete, Engage), has shown similarly strong results—but serves only a tiny fraction of those eligible.20

Another valuable program is College Discovery (CD), which provides a range of supports on community college campuses for students with defined educational and economic needs. Celebrating its 60th year of operation in 2023, CD offers supplemental instruction and advisement as well as need-based financial aid and peer mentoring. Operating across six CUNY community college campuses (all except Guttman), the program serves a total of 817 students.

Lehman College student Jeremy Quinones benefitted from CD after he was accepted at Hostos Community College even before getting on campus in the fall. “That summer the CD staff told me they were going to check our math and English to see if we needed to take pre-college courses,” he recalls. “I was able to get those out of the way in the summer, and start that fall without having to waste time taking pre-math and pre-English.” He cites CD’s providing support through a stipend for textbooks and access to counseling and tutors.

As he was transferring from Hostos to Lehman College, Quinones was offered a job as a peer mentor with College Discovery. “I loved the support I received when I was in the program, so being able to be a part of that experience for other students was really special for me.” Working with a cohort of up to 30 students, he keeps in touch with them throughout the semester and offers help with everything from keeping financial aid up to date to completing transfer applications and all-purpose discussion.

When a student in CD transfers to a senior CUNY college, they sometimes can transition into SEEK, the equivalent program to CD for students seeking a bachelor’s degree. SEEK serves 4,625 students across 11 senior colleges. Unfortunately for him, Quinones was not able to join the program. “I filled out my form and sent it in twice, and both times I was told they put me on a wait list. When I reached back out, they told me I was still on a wait list, and finally they said they couldn’t take me right now.”

Still enrolled at Lehman following a difficult change of major, Quinones feels that SEEK would have made his path easier. “I don’t feel as well connected at Lehman as I did at Hostos,” he explains. “I don’t have that community anymore. They literally tell you, when you do your first couple years at Hostos or BMCC, that this program goes with you. But when I transferred, and over the two years plus that I’ve spent at Lehman, I’ve had none of that.”

For many aspiring transfer students, a program that would enable community college supports to continue after transfer—from ASAP into ACE, or College Discovery to SEEK—could mitigate transfer shock and improve outcomes. Ensuring the continuation of these supports across colleges, however, would require a commitment from both policymakers and CUNY leaders to grow and reliably fund these initiatives with transfer students in mind.

Bronx Transfer Affinity Group: supplementing student supports

The idea of providing a stronger sense of community for transfer students animates the Bronx Transfer Affinity Group (BTAG), a collaboration that includes Hostos and Lehman as well as Borough of Manhattan Community College, Bronx Community College, and Guttman Community College. The Bronx Opportunity Network (BON), itself a collective of eight Bronx-based community-based organizations that provide student-facing social services in the borough, is also part of BTAG. In the words of one supporting administrator, BTAG is there to help students form a “graduation habit” in which they complete associate’s degrees at their home college and then transfer to Lehman.

From the BON’s perspective, the partnership with BTAG validates and systematizes the work that these nonprofit community-based organizations were already doing outside the CUNY system, explains Theory Thompson, chief program officer for educational and vocational programs at Good Shepherd Services and a co-chair of the BON. “We go to BTAG meetings and can provide real-time examples of when students trying to move from Bronx Community College to Lehman encounter certain obstacles, and what can be done about that.”

For Thompson, the key is to ensure that students feel connected to the resources and supports they require to be successful. “One of the most profound things I heard when we started the work was one young participant who said, ‘I don’t know why they assume we don’t need the same type of supports we had at our two-year schools.’ That resonated with me. I understand that they want to get them ready for the real world, but we also have a responsibility to make sure that students get the supports they need.”

BTAG helps leverage another best practice that has taken hold in the Bronx: pre-transfer advisement. This model comes closest to the vision of supporting community college students’ transfer goals from their first day on campus. According to Emily Denham, pre-transfer advisor at Lehman College, this is no coincidence. “We’re thinking about this as a four-year experience,” she says. “Long-term, big picture, and catching them early to make sure they’re doing what they need to do and taking what courses they need to take.”

To that end, Denham travels a circuit of the community colleges from which students are most likely to transfer into Lehman: Bronx Community College, Hostos, and Guttman from the CUNY system, as well as Westchester Community College. “I try to ensure that whatever they were doing at the two-year school will optimize their transfer credits at Lehman,” she explains. “I start off by asking what it is they want to do at Lehman, and then try to make sure they take the right courses that will transfer.”

Baruch Business Academy: Guaranteeing admissions to streamline the transfer process

Baruch College enjoys one of the strongest academic reputations of any CUNY campus, with its Zicklin School of Business particularly esteemed as a talent source for some of New York City’s most prominent financial services firms. But as Baruch conducted a broad review of its policies around diversity, equity, and inclusion several years ago, a problem came into focus—particularly at Zicklin.

“We looked at data and found that though we were admitting a substantial number of community college transfer students from under-represented communities, they were not enrolling at the same rate as other students,” recalls Sonali Hazarika, executive director of undergraduate programs at Zicklin and an associate professor of finance. “We decided to redouble our efforts to make sure students of all backgrounds, but especially Black and Latinx students, knew they were not only welcome but could thrive at our school.”

What emerged was the Baruch Business Academy, an agreement of Baruch with three CUNY community colleges—Borough of Manhattan, LaGuardia, and Queensborough—that students who complete an associate’s in science degree in business administration and meet additional academic criteria are guaranteed admission to the Zicklin School of Business. Qualifying students do not even have to file a CUNY transfer application. Other benefits include priority registration for courses and peer-to-peer mentoring from current Zicklin students both before and after transferring into Baruch. A number of these elements were inspired by the CUNY Justice Academy, a highly regarded partnership of seven CUNY community colleges with the John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

Launched as a pilot in fall 2021 with 25 students, the Baruch Business Academy has grown to 275 members, and expects enrollment to continue to increase. Data suggest that the Academy is achieving its goal of engaging a diverse group of students. Discussions are underway to expand to additional community colleges.

One particularly promising aspect of the Baruch Business Academy is its commitment to ensuring that transfer students get access to the networking and internship experiences that are often decisive in securing career-track employment following graduation. “Some want internships but can’t leave their barista job because it pays the bills,” says Ellen Stein, director of Baruch’s Starr Career Development Center serving undergraduate students. “It's important to recognize that real-world structural economic hurdles can impede student success. We provide a variety of support services to help students address these challenges.”

As part of their efforts to expand these pathways, the Baruch team invites recruiters from some of the city’s top firms to participate in information sessions and career fairs. “Baruch is a destination for recruiters since they know that our transfer students are diverse and can bring valuable different perspectives and skills to the workplace.,” says Sandra Kupprat, associate director at Starr Career Development Center. “Conversely, it is more meaningful for students of color to hear from recruiters with similar backgrounds saying, ‘We want to hire people like you,’—that gives the students confidence that they can really succeed in corporate America after graduation. I’ve heard students say, ‘It’s because of the recruiter I met that I want to work at that company.’”

Learning from Elsewhere: Virginia’s ADVANCE program

Operating across seven campuses and serving about 80,000 total students, Northern Virginia Community College (NOVA) is roughly comparable in size and scope to the community college portfolio within CUNY. Perhaps not surprisingly, NOVA faced many of the same issues with respect to transfer. The approach it took to addressing those issues somewhat resembles the Baruch Business Academy in structure and intention, but operates on a much larger scale.

In fall 2018, NOVA struck a partnership with George Mason University (GMU) to launch the ADVANCE program with an initial cohort of about 150 students. ADVANCE guarantees seamless admission into GMU for all students who meet eligibility criteria, including enrollment in a NOVA associate degree program, maintaining at least a 2.0 GPA, and having earned no more than 30 college credits before applying. Efforts to align curricula among institutions and departments have ensured that every credit a student earns at NOVA will transfer toward their GMU degree program.

By 2022, ADVANCE had grown to serve 3,300 students. The majority of ADVANCE students are non-white, and about 40 percent are low-income. The program includes 87 academic pathways or majors through which ADVANCE students can earn both an associate’s and a bachelor’s degree within four years. Students who follow this path save approximately $15,000 in tuition costs compared to four-year GMU students, while realizing the economic benefits of a four-year degree21

Participants can take some classes at GMU while enrolled at NOVA, as well as accessing facilities, specialized coaching, and other resources at both schools. The coaching includes regular meetings with fellow students who are further along in the program and can provide support related to coursework as well as challenges beyond the classroom. To date, ADVANCE students have a one-year retention rate at GMU which is 20 percentage points higher than the national average for community college students.

Endnotes

1 Center for an Urban Future analysis of data from CUNY Wage Dashboard, https://insights.cuny.edu/t/CUNYGuest/views/CUNY_Wage_Dashboard_BIRD/Wage.

2 https://www.cuny.edu/about/administration/offices/oira/policy/a2b/about-2/

3 Pooja Patel et al, “Archiving Degree Audit Data to Measure and Reduce Lost Transfer Credit,” Ithaka S+R, February 2022.

4 CUNY Transfer Explorer, “Percentage of Graduates by Transfer or Non-Transfer Student Status, 2021-22”

5 New York City Comptroller, “CUNY’s Contribution to the Economy,” March 12, 2021.

6 CUNY Newswire, “New Study Confirms CUNY’s Power as National Engine of Economic Mobility,” June 17, 2020.

7 CUNY Tuition and Fees

8 David B. Monaghan and Paul Attewell, “The Community College Route to the Bachelor’s Degree,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, Volume 37, Issue 1, March 2015, Pages 70-91.

9 National Student Clearinghouse, “The Challenge of Transferring College Credits,” Dec. 5, 2017.

10 CUNY A2B, “Credit Loss and Transfer Shock: Longitudinal Analysis of Students who Transfer from Associate to Bachelor’s Programs,” April 2022.

11 Beyond Transfer Policy Advisory Board, "Unpacking Financial Disincentives: Why and How they Stymie Degree-Applicable Credit Mobility and Equitable Transfer Outcomes,” February 2023.

12 Center for an Urban Future, “Playing New York City’s ACE Card,” March 2023, https://nycfuture.org/research/playing-new-york-citys-ace-card.

13 Vita Rabinowitz, Yoshiko Oka and Alexandra W. Logue, “What Faculty Know (and Don’t Know) about Transfer—and Why It Matters,” Inside Higher Ed, September 7, 2022.

14 CUNY Office of Policy Research, “Transfer Application and Transfer Melt: Longitudinal Analysis of Students who Start in Associate Programs,” July 2021.

15 “Credit Loss and Transfer Shock.” Importantly, however, 40 percent of students who transfer from a two- to a four-year program see their GPAs improve after transfer. Additionally, researchers have found that after accounting for baseline changes from one semester to another, only 16 percent of transfer students show a decrease in GPA in excess of expectations.

16 Ibid.

17 CUNY Transfer Explorer, accessed on July 5, 2023; online at https://explorer.cuny.edu/course-transfer/123117/1

18 As of Fall 2022, total enrollment at CUNY’s seven community colleges was 67,584, with 35,687 enrolled full-time and 31,897 enrolled part-time. Thus, the 42 percent of full-time students in ASAP would represent 22 percent of all community college students.

19 CUNY ASAP

20 Center for an Urban Future, “Playing New York City’s Ace Card.”

21 PBS, “Universities, community colleges partner to help transfer students earn degrees,” Sept. 27, 2022.

At the same time, transfer performance is wildly uneven across CUNY’s dozen senior colleges. Three-year graduation rates following transfer range from a high of 66.6 percent at Baruch College to 26.5 percent at New York City College of Technology (City Tech). Four CUNY colleges—Baruch, John Jay, Lehman, and the School of Professional Studies—have transfer graduation rates above 50 percent. Four others—Medgar Evers, City Tech, College of Staten Island, and York—see fewer than 40 percent of their transfer students earn bachelor’s degrees within three years.

At the same time, transfer performance is wildly uneven across CUNY’s dozen senior colleges. Three-year graduation rates following transfer range from a high of 66.6 percent at Baruch College to 26.5 percent at New York City College of Technology (City Tech). Four CUNY colleges—Baruch, John Jay, Lehman, and the School of Professional Studies—have transfer graduation rates above 50 percent. Four others—Medgar Evers, City Tech, College of Staten Island, and York—see fewer than 40 percent of their transfer students earn bachelor’s degrees within three years.

Building on this progress will require a new level of attention from city and state leaders and CUNY on addressing pain points in the transfer process. For starters, too often CUNY’s senior colleges will not accept at least some credits earned at the community college level toward the transferring student’s major, which costs students time, money, and lost academic momentum. Many students who do transfer end up with “excess” elective credits—with related costs that financial aid programs will not cover.

Building on this progress will require a new level of attention from city and state leaders and CUNY on addressing pain points in the transfer process. For starters, too often CUNY’s senior colleges will not accept at least some credits earned at the community college level toward the transferring student’s major, which costs students time, money, and lost academic momentum. Many students who do transfer end up with “excess” elective credits—with related costs that financial aid programs will not cover.