If there is one institution in New York ideally positioned to help ensure an inclusive economic recovery from the COVID-19 crisis, it is arguably the city’s community colleges. CUNY’s seven community colleges offer low-income New Yorkers the most accessible path to a college credential, the new baseline for obtaining well-paying jobs in the post-pandemic economy. But though these institutions have enormous potential to be this generation’s elevator to the middle class, that promise will not be fully realized without a fundamental shift in how the city and state help New York’s mostly low-income community college students afford the true costs of college.

Every year, thousands of students enrolled at CUNY community colleges drop out without earning a credential. Although some do so because of a lack of academic preparedness, our research finds that far more students leave school because of financial barriers that make it untenable to continue attending classes. Perhaps surprisingly, the main financial hurdle is not tuition but rather a variety of non-tuition financial challenges—from paying for a MetroCard to covering a parent’s emergency medical bill.

Although there is a popular perception that tuition costs impose the greatest burden on college students, a majority of CUNY community college students attend school tuition-free, thanks to federal and state tuition assistance programs. Indeed, the average full-time CUNY community college student received approximately $7,503 in aid last year.

While some community college students in the city do struggle with tuition, far more are getting tripped up by an array of other financial challenges: 1) the struggle to afford essential non-tuition expenses—including transportation, textbooks, Internet service, childcare, and food; 2) the ability to deal with sudden financial emergencies; and 3) the need to work long hours while attending college, which often impacts academic performance and, in turn, causes students to lose the government-backed tuition assistance that is predicated on maintaining a 2.0 grade point average.

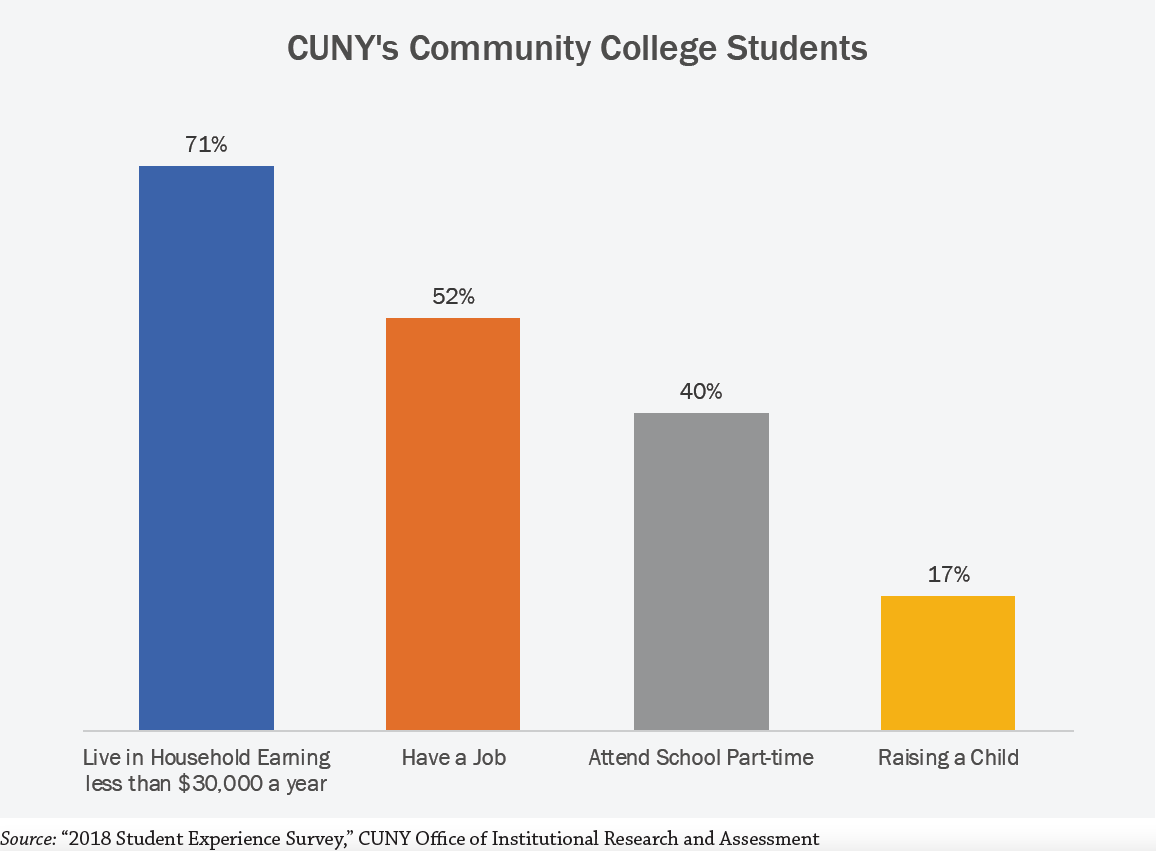

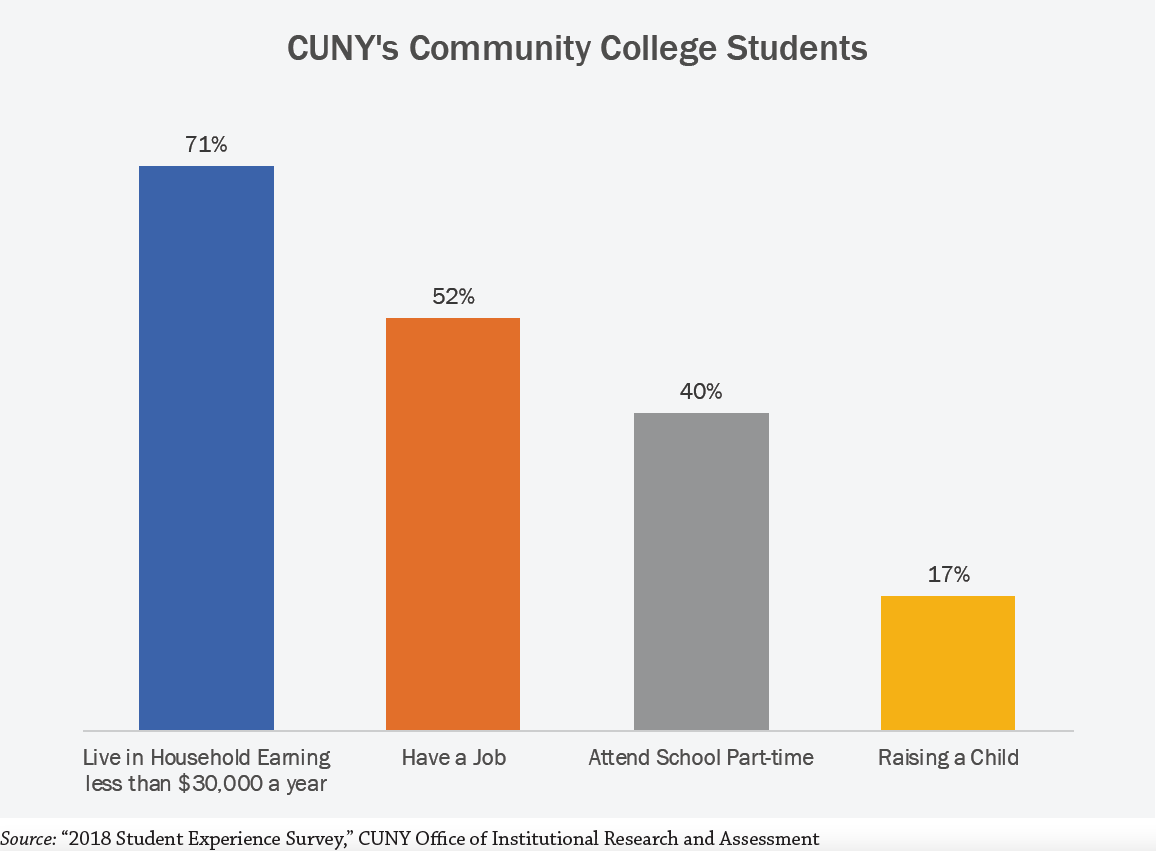

These non-tuition challenges are all too common in New York City, where nearly three-quarters of community college students (71 percent) live in households earning less than $30,000 a year; one in six students (17 percent) attend school while raising a child, 52 percent are working—the majority for more than 20 hours a week; and more than 40 percent attend school part-time, limiting options for aid and support.

Helping far more of these New Yorkers succeed in college—and gain access to good jobs—will require more than just tuition assistance. These mostly low-income students succeed in college at high rates when receiving help with non-tuition costs—through programs such as CUNY ASAP, which gives participating students textbooks and a MetroCard. But too few students currently get this help. Indeed, as this report shows, New York has some of the nation’s most generous programs that cover tuition costs but relatively little to help with the mountain of non-tuition costs.

This report, made possible thanks to a grant from the Deutsche Bank Americas Foundation, is the latest in a series of studies by the Center for an Urban Future focused on building a more inclusive economy in New York. It is informed by interviews with over 50 experts in college persistence and basic needs access—including staff at community-based organizations (CBOs), faculty and administrators at CUNY, and student advisors—and over 50 conversations with students at every CUNY community college, as well as an analysis of data from CUNY, New York State’s Higher Education Services Corporation, the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, and the Hope Center at Temple University’s #RealCollege Survey. The report concludes with concrete recommendations for how CUNY and policymakers across New York City and State can work together to improve college completion by tackling the non-tuition financial barriers that are holding students back.

The stakes are high: A college credential is an increasingly essential prerequisite for future economic opportunity. In New York City, residents with a bachelor’s degree earn twice as much as those who only have a high school diploma ($58,076 versus $28,781). Most of the city’s fastest-growing middle-income jobs, in fields like tech, healthcare, and the creative economy, require at least an associate degree. And as job losses mount in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, New Yorkers with a college credential are more likely to retain their employment and have an advantage in a flooded labor market. Community colleges—which serve low-income, first-generation students all over the city and are the gateway to a bachelor’s degree for many of their graduates—are uniquely well-positioned to respond to that need.

The problem is that far too many of the city’s community college students exit without a degree or credential. Just 27 percent of full-time, first-time CUNY community college students earn a two-year associate degree within three years. By that time, more than half have dropped out. Several factors contribute to the city’s low graduation rates—including lack of academic readiness, insufficient financial aid, and stretched systems of guidance and support. But across more than one hundred interviews with students, administrators, and community-based organizations—supported by a review of all available surveys of CUNY community college students—this report finds strong evidence to suggest that the greatest barriers to completion for New York City community college students are the non-tuition costs of a college education. These include a MetroCard, textbooks, a home Internet connection, childcare, food, housing, and emergency expenses—and the constant pressure to choose work over class.

In dozens of interviews we conducted, students, advisors, faculty, and administrators all agreed that thousands of CUNY students drop out each year because of these non-tuition costs.

“Non-tuition barriers are huge,” says Judith Lorimer, director of DegreesNYC at Goddard Riverside’s Options Center, an organization focused on closing the city’s postsecondary attainment gaps. “It doesn’t matter how small the amount is, it can form a barrier to being able to stay in school. We’ve had students who didn’t have a MetroCard and so stopped going to school. We’ve given students money to eat. The costs outside of tuition are forcing CUNY students to stop out or drop out.”

“I couldn’t afford the transportation. I had no choice but to leave,” says Kiara, a former LaGuardia student who dropped out in the spring of 2019 after she lost her job and could no longer afford the commute. (All students interviewed for this report are identified by their first name only.)

From a MetroCard and textbooks to childcare: the non-tuition barriers derailing students

The challenge of affording a MetroCard came up more than any other single barrier in the course of our research. Ninety percent of CUNY community college students commute to school primarily via public transit. For full-time students, a MetroCard will usually cost more than $1,000 each school year. “I can think of countless students who have dropped out of college because they can’t afford the price of a monthly MetroCard,” says Cassie Magesis, director of postsecondary access at the Urban Assembly, a nonprofit that supports a network of 23 public schools across the city.

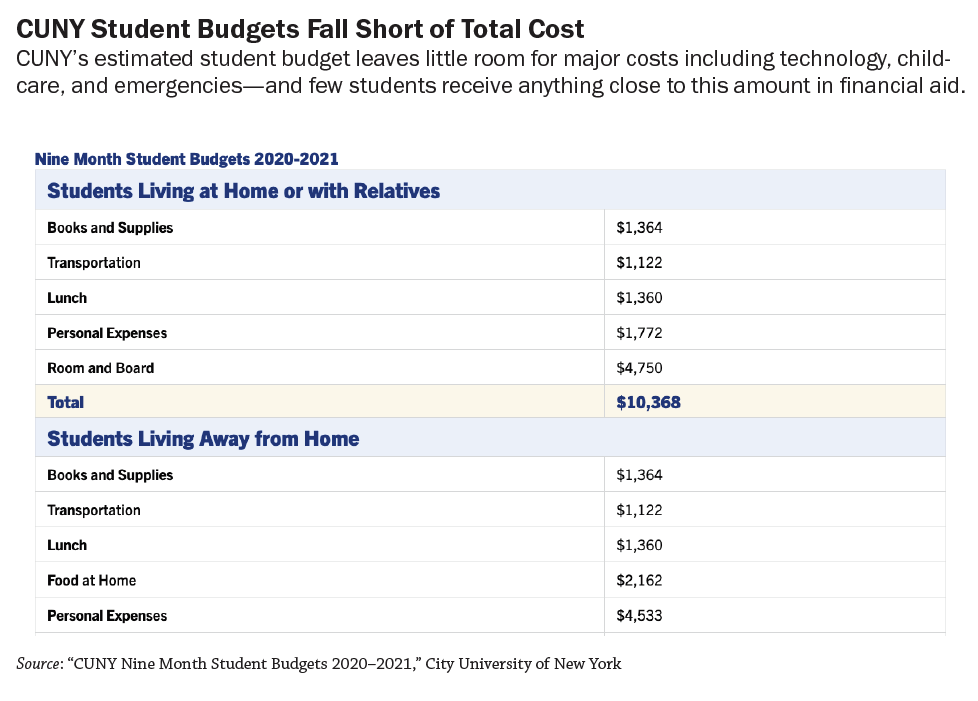

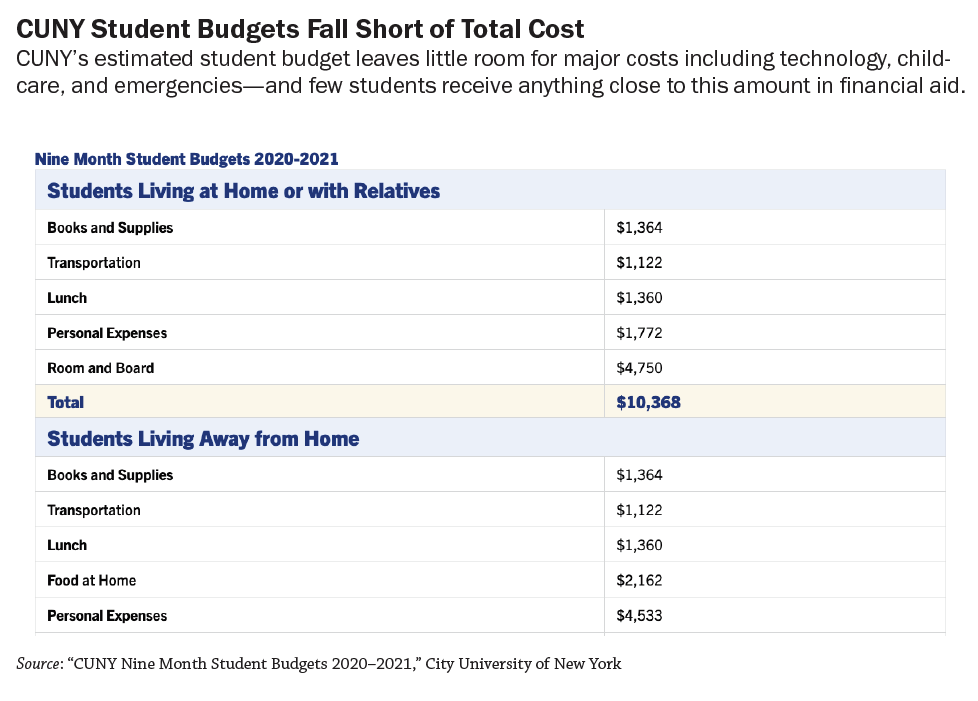

Many other students struggle to afford textbooks and other required supplies, which cost the average community college student $1,364 per year, according to CUNY. At the Borough of Manhattan Community College (BMCC), the required textbook and lab manual for the spring 2021 Biology 1 course together costs $165.55 at the campus bookstore. In STEM classes, students often have an additional cost: They’re required to buy an access code to an online platform used to submit quizzes and assignments, which cannot be bought used. Students and advisors told us it is not unusual for a textbook-and-access-code bundle to cost $200 to $300.

Internet service and computers add another burden, one that was especially problematic during the past year when most courses went online and students no longer could access campus computer labs. The most affordable home Internet service usually costs $500 to $600 a year, while a basic laptop costs an additional $300.

For thousands of students, childcare costs add another layer of expense. Indeed, there are nearly three times as many CUNY community college students who are attending school while raising children (roughly 16,000) than the entire undergraduate population at Columbia University (6,000). Overall, approximately 17 percent of CUNY community college students are parents, and for the student-parents we interviewed, private childcare costs at least $600 per month unless they qualified for Head Start.

To its credit, CUNY now offers on-campus childcare centers that are affordable, high quality, and an invaluable support system for the students who use them. But the 16 centers serve a total of about 1,300 students per year, a small fraction of the students who are raising children. Indeed, just 11 percent of community college student-parents report using an on-campus childcare center, while 39 percent pay for off-campus childcare. One reason for the low uptake is that the on-campus childcare centers do not accept children under two, which means students with infant children have to find alternative childcare or wait to start college.

Most community college students in the city also struggle with food and housing insecurity, and many encounter their biggest hurdles when financial emergencies arise, often requiring them to dip into money set aside for tuition to meet the sudden need.

Student supports for low-income high school students vanish in community college

Many of the same low-income students enrolled at CUNY community colleges benefited from free breakfast and lunch when attending public high schools across the five boroughs. In high school, students also were given a free MetroCard. But while their financial situation didn’t necessarily change between graduating high school and entering community college, those supports ended.

“We should think of higher education as a K-14 system and extend any support or service provided for K-12 by two years,” CUNY Chancellor Félix Matos-Rodriguez noted at a recent Center for an Urban Future forum. “That would make community colleges effectively free. You would get breakfast and lunch, so the food insecurity issue would be substantially addressed, and [you would also receive] a discount MetroCard. Instead, students lose these supports between May and September.”

Of course, CUNY doesn’t have the resources to do this on its own. But the city and state could provide the funding to cover MetroCards for all community college students and help subsidize other non-tuition costs like books and IT expenses.

Most of NYC’s community college students receive tuition assistance, but too little help with other costs

To be sure, tuition is also a heavy burden for many students. Current annual CUNY community college tuition for full-time students who are New York residents is $4,800, plus fees. This is more than four times the tuition bill for community college students in California ($1,104) and higher than the national average for two-year public colleges ($3,770). In addition, New York’s tuition costs have risen in recent years: community college tuition is up from $3,150 in 2009, a 52 percent increase over the past decade.

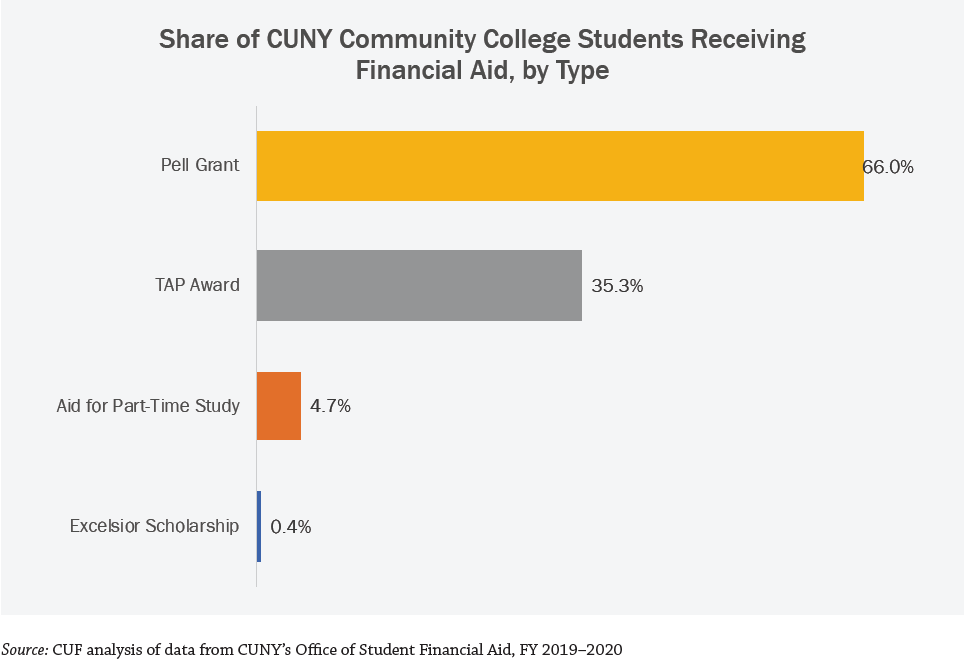

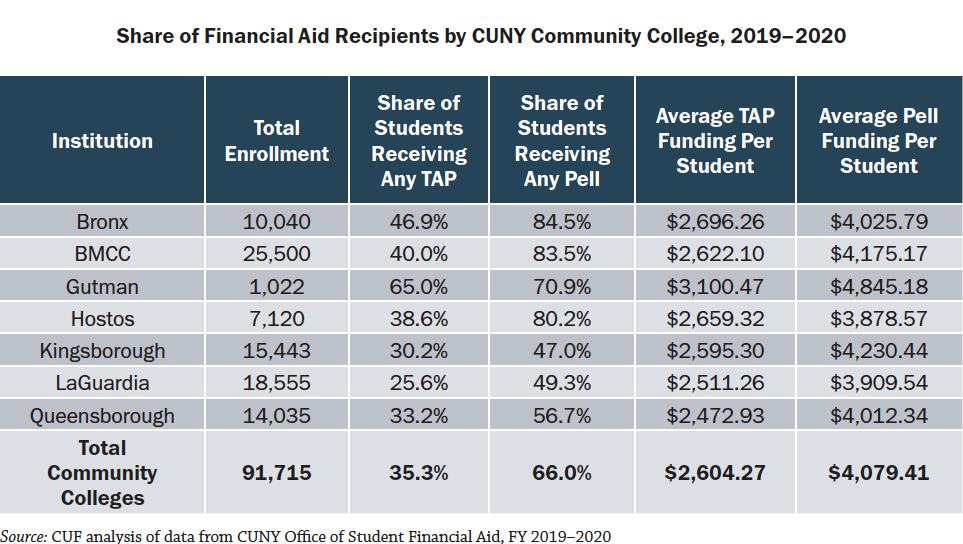

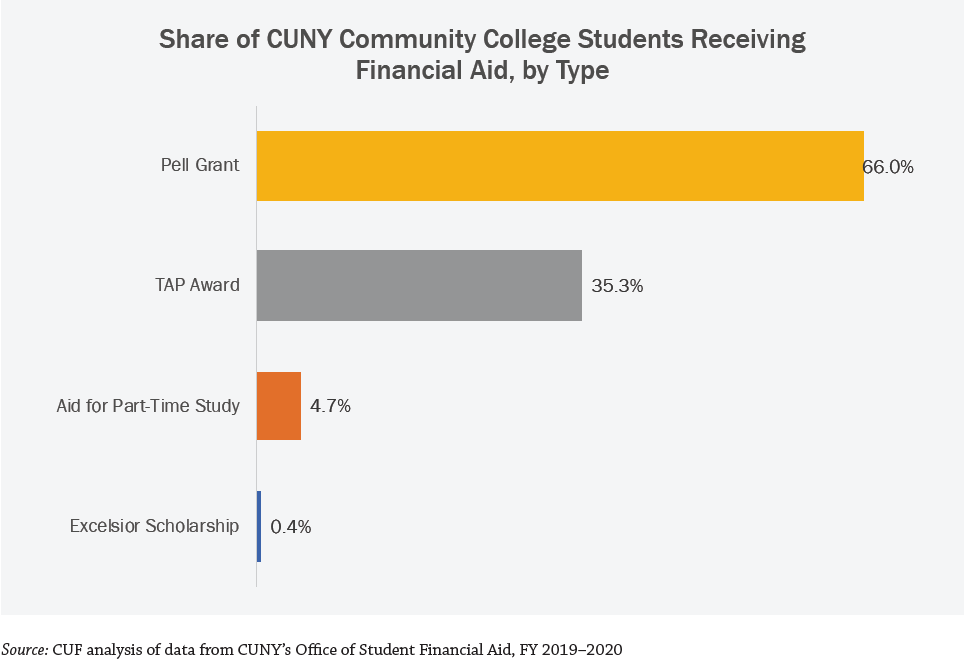

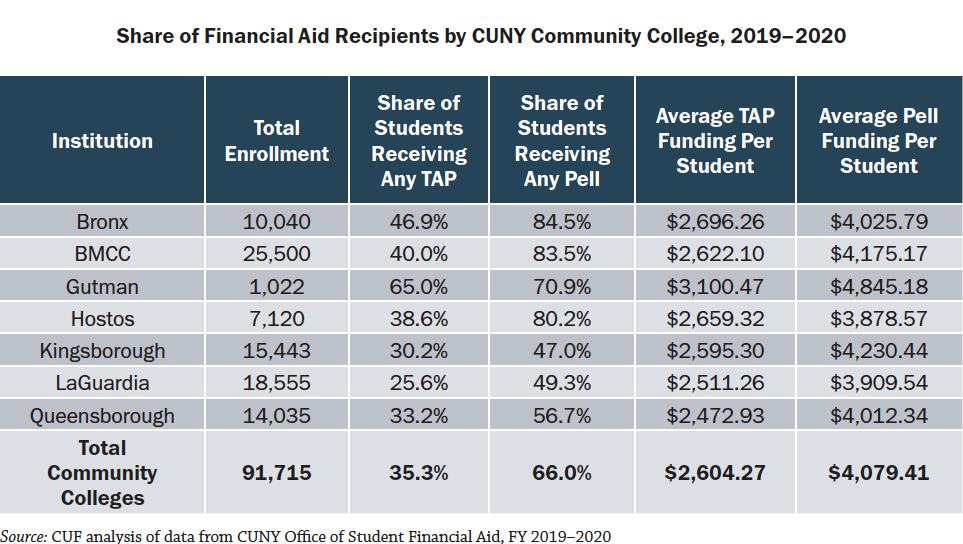

But a majority of CUNY’s community college students effectively pay no tuition, thanks to federal and state tuition assistance programs. Two-thirds (66 percent) of CUNY community college students receive federal Pell grants, and 35 percent receive aid from the state’s Tuition Assistance Program (TAP). Those grants allow over 58 percent of all full-time CUNY undergraduates to attend college tuition-free.

The problem is that even for those students paying no tuition, other costs can be debilitating. CUNY estimates that the average community college student who lives at home will need $10,368 for each nine-month school year to cover the non-tuition costs of attendance, including transportation, meals, personal expenses, books, and supplies. For students living independently, that figure rises to $24,446—more than many students’ entire households earn in a year.

“Even if they receive full financial aid, they may still not be able to pay for books and other personal needs that they may have,” says Rhonda Mouton, program director for LaGuardia CARES (College Access for Retention and Economic Success), which connects students at LaGuardia Community College with resources, referrals and local community services to overcome financial barriers to graduation. “Eighty-five percent of students at LaGuardia receive financial aid. But books, equipment, transportation, housing, and food insecurity are factors that may remain. If a student is impacted by those things, they will drop out of school.”

But relatively few community college students have much, if any, support for these non-tuition costs. At best, students who receive full Pell and TAP grant awards would receive around $11,000 in grant aid in the 2020–2021 academic year—approximately $5,200 to cover tuition and fees, and a $6,000 refund check, which can be applied toward some of these expenses. Even in that best-case scenario, a student living independently would have to come up with thousands of dollars on their own. Moreover, just two-thirds of community college students (66 percent) received a Pell Grant of any amount, and only 35 percent received a TAP award. For community college students who received both, the average award totaled about $7,503—leaving just $2,303 left over after tuition and fees to cover a full year of costs. For the majority of students, additional grant funding on top of tuition is minimal.

Non-tuition financial barriers force most students to work, impacting academic performance and jeopardizing students’ financial aid.

The lack of public aid for these other expenses precipitates the other huge reason for students to drop out early: an alarmingly high percentage of New York’s community college students work more than 20 hours a week.

Overall, more than 52 percent of full-time CUNY community college students work during any given semester. And for those students with paid jobs, 56 percent work more than 20 hours per week. By comparison, the average Harvard senior with a job works just 8 hours per week.

The high share of students who are working full-time or nearly full-time is problematic since research shows that academic progress often suffers when students work more than 15 hours a week. “The college graduation rate is low for a reason: People need to work,” says Daniel Diaz, executive director of East Side House Settlement in the Bronx.

“That’s the biggest reason why people don’t complete their schooling—because they have to work,” adds Amara, a part-time nursing student in her second year at Hostos Community College who works 48 hours a week as a home health aide. “Last semester, three of my friends dropped out because they couldn’t keep up,” she says.

Not surprisingly, students who work so many hours often struggle to keep up with their coursework or studying. Some miss classes because of the heavy workload. Others need to drop out of tutoring programs that helped them keep pace academically. “Students have to balance their study schedule and work schedule, and sometimes there is not enough time to do both,” says Mouton of LaGuardia CARES. “Students are often fatigued and overworked, and sometimes going to school is a challenge for those reasons.”

Unfortunately, the repercussions of this go beyond poor grades for the city’s community college students. That’s because students need to maintain “satisfactory academic progress” (SAP) to hold onto their financial aid. SAP requirements vary for federal and state aid but generally require students to maintain a grade point average (GPA) of at least 2.0 to continue receiving aid through graduation. If progress slips, students can lose their financial aid and must file an appeal for a chance at getting it back. Without their TAP and Pell grants, many students cannot afford to stay enrolled.

Every year, an alarming number of CUNY students lose their financial aid, and interviews suggest that a significant share of those who do invariably drop out. Advisors and nonprofit leaders we spoke with suggest that students’ financial stress often contributes to the loss of aid. “What’s going on behind the scenes that’s leading to poor academic performance at school?” asks Allison Palmer, executive director of New Settlement’s College Access Center. “A lot of times it’s that the student is hungry or homeless or they just didn’t have money for a MetroCard to get to school that month, and then it’s poor academic performance that leads to a student stopping out.”

CUNY can’t solve these challenges on its own

In recent years, CUNY has taken important steps to address non-tuition financial barriers. Every community college now has an on-campus food pantry and an Advocacy and Resource Center that can screen students for benefits and help them access other supports, including legal aid and emergency grants. Five of the seven community colleges have childcare centers. And privately funded emergency grant programs help students with costs that might have kept them from persisting in school. Moreover, its highly successful ASAP initiative, which has been proven to more than double graduation rates at CUNY’s community colleges, provides participating students with free textbooks and a monthly MetroCard, acknowledging that costs outside of tuition can be barriers to earning a degree.

But these efforts only begin to address the non-tuition financial stresses facing New York’s community college students. Making a bigger difference will undoubtedly require leadership—and financial support—from city and state government.

Indeed, while CUNY undoubtedly can do more to build on its recent efforts to boost student success—for instance, by continuing to expand academic advising, complete the phase-out of remedial education programs with credit-bearing courses and summer bootcamps, and simplify academic pathways—much of the power to address the non-tuition financial barriers facing community college students rests with the city and state.

City and state government officials have begun to help. Mayor de Blasio provided $42 million that enabled CUNY to significantly expand ASAP in 2015, and the City Council dedicated $1 million in its FY 2020 budget for a pilot program to increase food access at CUNY colleges. The state expanded SNAP eligibility for community college students and established the Family Empowerment Community College Pilot Program, an initiative to support 400 solo parents at CUNY and SUNY community colleges per year by providing free enrollment at a school’s childcare center, advising, and academic and career support. In addition, New York State’s 2021 budget included $8 million to expand CUNY’s open educational resource offerings that help to reduce the costs of textbooks.

But city and state policymakers could do far more.

Although Mayor de Blasio rightly made affordability a central issue of his mayoralty, his administration has not done enough to help students with the various non-tuition barriers that make their college experience so unaffordable.

Governor Cuomo’s widely touted free tuition program—the Excelsior Scholarship—was set up in a way that almost completely bypasses CUNY’s lower-income community college students. Our analysis of Excelsior awards from the first two years of the program finds that only 335 scholarships, amounting to less than $1.3 million, were awarded to students across CUNY’s seven community college campuses in 2018—just 1 percent of the total funding awarded that year. Just nine students at Hostos Community College and ten students at Bronx Community College received awards in 2018, the lowest numbers of any colleges in the state.

The governor’s 2018 No Student Goes Hungry Initiative importantly requires all New York public colleges to establish on-campus food pantries but leaves the colleges to come up with the funding. In addition, the governor and state legislators have not taken steps that would enable the nearly 40 percent of CUNY community college students who attend on a part-time basis to qualify for the state’s Tuition Assistance Program.

.png)

Source: CUF analysis of enacted state budget appropriations for CUNY Community College operations, FY2000 and FY2020, adjusted for inflation

Meanwhile, state funding for CUNY has stagnated. Since 2000, baselined state funding for CUNY community colleges is down nearly 7 percent on a per-student basis, from $2,927 per student in 2000 to $2,740 per student in 2019 (adjusted for inflation). Per-student funding needs to keep pace in order for the colleges to be able to provide the supports students need to persist in college.

City and state policymakers have also missed opportunities to leverage the community-based organizations that are so well-positioned to help New York’s low-income college students persist in college. Many of these nonprofits receive government grants to help teens earn a high school degree and apply to college. But there are few government funding sources that would enable the organizations to help these same students persist in college. “It has been very difficult, nearly impossible, to get any funding to help support our students once they are in college,” says Christie Hodgkins, vice president at CAMBA, a Brooklyn-based social services nonprofit.

Directors and staff at CBOs say they want to support students in college, and many are working to expand college success programs. But without a consistent source of city and state funding dedicated to college success efforts, many organizations report relying on funding from private donors to support their work with college students or even operating some of their most critical services at a loss. Across multiple interviews, CBO staff cite inflexible funding rules as an impediment, including in grants from the city’s Department of Youth and Community Development, the city agency best suited to support college persistence work. If given the resources and flexibility, say CBO staff, more would redirect funding to develop programs that respond to the needs they see among low-income college students, like college coaching and mentorship programs, and help completing Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) forms.

What New York City and State should do

Our research shows the harmful effect of non-tuition financial barriers on college persistence. On an individual level, these barriers interfere with a student’s ability to earn a credential; on a system-wide level, they undermine the mission of New York City’s community colleges to serve as powerful catalysts for economic opportunity. City and state government officials have the power to change this, but it will require them to make significant new investments both to expand the CUNY initiatives that are having an impact and to develop new programs to counteract the most persistent and destructive economic barriers.

In this effort, New York can draw from emerging models around the country. California offers financial aid grants that low-income students can use for housing, childcare, and other non-tuition costs, while Washington is one of a few states to implement state-funded emergency aid (both states have also made community college tuition-free). Los Angeles and Chicago are bringing CBOs onto community college campuses to address issues like housing insecurity. A new online platform that partners with colleges is getting emergency aid to students more quickly, and in an on-campus cafeteria at the University of Kentucky, lunch is always a dollar.

New York City and State—including the next mayor, City Council members, and leaders in the State Legislature—should take strong steps to expand financial support for low-income students, with a focus on overcoming persistent nontuition financial barriers. City leaders can act boldly to protect and expand the highly successful CUNY ASAP model to every community college student, which over time could result in more than 16,000 additional community college graduates every year. Other options include providing every community college student with a free MetroCard, expanding on-campus childcare, and restoring the full range of support services on every campus previously provided through the Single Stop centers. Likewise, the mayor should direct the Department of Youth and Community Development (DYCD) to launch new RFPs designed to encourage community-based organizations to continue and scale up support for college persistence.

The State Legislature can also play a major role in supporting college success by striving for free tuition while embracing lower-cost alternatives that reduce nontuition barriers and expand TAP to serve more low-income students. Meanwhile, CUNY should consider the targeted expansion of key services, like keeping campus libraries open until midnight to accommodate working students and committing to screen every student for benefits eligibility, helping thousands of students access free support for food and other basic needs.

As our research makes plain, the non-tuition financial barriers facing community college students are pervasive drivers of low graduation rates and stand in the way of economic mobility. This report concludes with concrete recommendations for city and state leaders, CUNY, philanthropy, and community-based organization to knock down the non-tuition financial barriers that keep students from graduating and ensure that far more low-income New Yorkers are able to succeed in college.

.png)