Governor Hochul and the State Legislature have taken bold steps to help New York become a global leader in artificial intelligence (AI) and increase employment in the broader tech sector. Indeed, over the past decade, the state’s tech sector has grown 32 percent—nearly five times faster than the overall economy. But the state is lagging well behind in policies and investments to ensure that New Yorkers from Buffalo to the Bronx are prepared with the foundational digital and computational skills that power today’s tech economy—and that will be essential to accessing the well-paying careers of tomorrow.

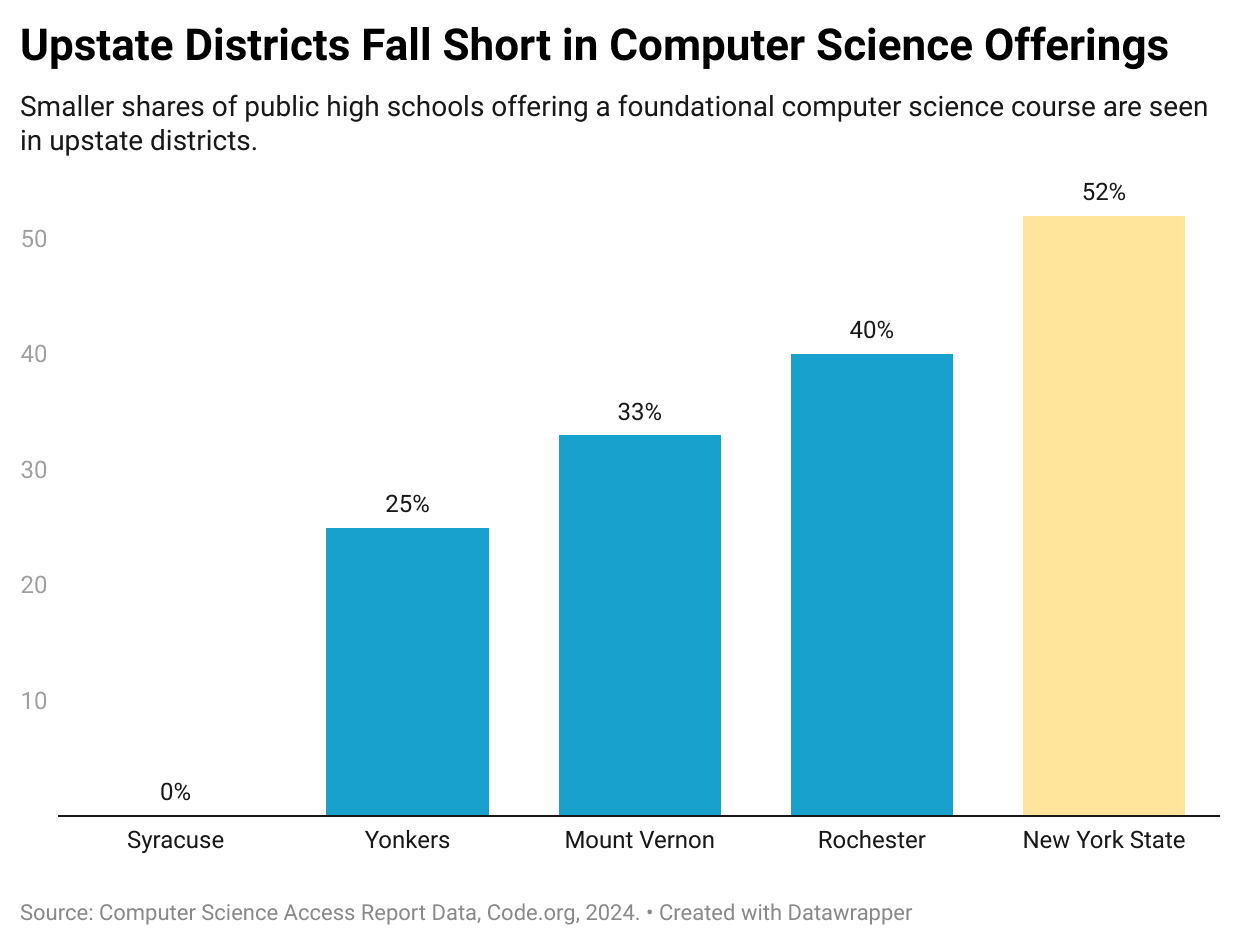

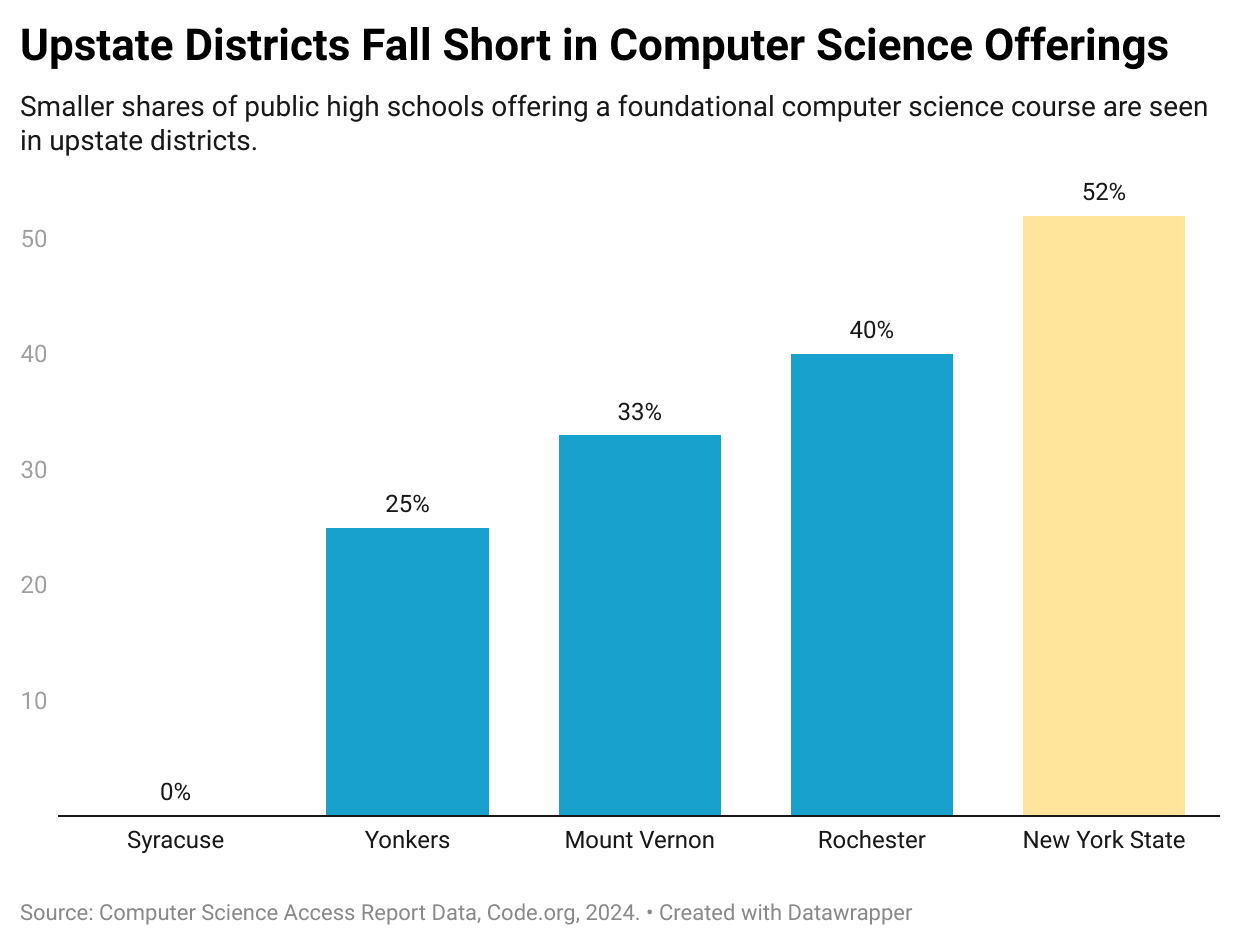

State policymakers have significant work to do in what may be the most critical area of all for preparing New Yorkers to succeed in a tech-driven economy: computing education in the state’s public K-12 schools. Today, New York ranks 37th among all other states and Washington, D.C., with only 52 percent of public high schools offering at least a foundational computer science course. That’s below the national average of 60 percent, and well behind leaders like Massachusetts (83 percent), New Jersey (86 percent), Arkansas (100 percent), and Maryland (100 percent).1

.png)

An even smaller share of students in the state’s public high schools—4.8 percent—are actually enrolled in foundational computer science courses. This is far below the 25 percent benchmark that many experts view as the minimum for universal exposure—meaning that over four years, nearly every student would take at least one computer science course before graduating high school.

Participation is even more limited among students from historically underrepresented backgrounds. Across New York State, just 57 percent of Black students attend a school that offers a foundational computer science course, compared to 67 percent of Hispanic students, 72 percent of white students, and 85 percent of Asian students. Girls make up only about 33 percent of students in computer science. Both urban (45 percent) and rural (45 percent) schools are much less likely to teach computing than suburban schools (79 percent).2

There’s also evidence that students attending schools upstate are especially far behind. While comprehensive data isn’t available for every district, computer science participation in New York City high schools (10.5 percent) is more than double the statewide average (4.8 percent)—suggesting that fewer than 2 percent of upstate high school students are taking computer science classes.3 Although New York City enrolls roughly 40 percent of all public school students statewide, it accounts for more than 80 percent of those taking a computer science course in high school. New York City may lead the state, but with only 10 percent of high school students taking computer science, schools across the five boroughs are still falling short.

Meanwhile, computer science offerings remain limited in many large upstate districts. In Syracuse, for example, not a single public high school offers a foundational computer science course. Statewide, 52 percent of high schools offer at least one computer science course, but that figure drops to just 40 percent in Rochester, 33 percent in Mount Vernon, and 25 percent in Yonkers.4

State policy decisions likely have contributed to these geographic, racial, ethnic, and gender gaps. New York is among a dwindling number of states that do not require all K–12 schools to offer computer science, do not mandate pre-service training in computing education for teacher candidates, and have yet to appoint a high-level state director of computing education.5 These policy gaps put New York’s students at a disadvantage, and pose a challenge to the state’s continued economic growth.

“If we’re investing in growing the economy without ensuring computer science access in our schools, we’ll end up seeing workers from other states filling the jobs we’ve created,” says Tom O’Connell, founder of CSForNY, a coalition working to expand high-quality computer science education in schools. “To build a strong talent pipeline, schools need support. That starts with the governor and state education leaders showing leadership on accountability and allocating resources for quality instruction. But at the district level right now, they’re not getting that.”

To prepare the next generation of New Yorkers for success in an increasingly AI-powered economy—and to close persistent opportunity gaps—Governor Hochul, the Board of Regents, and State Legislators must lay a stronger foundation for computing education across the K–12 system. In a world where AI can generate code and automate complex tasks, the most essential skill won’t be coding itself—it will be computational fluency: the ability to understand how these tools work, use them strategically, and critically evaluate their outputs. The students who thrive won’t just be users of AI—they’ll be the ones who know how to guide it, question it, and apply it effectively across fields. And even as the workforce faces significant disruptions, New Yorkers with those skills will be best positioned to adapt.

Supported by a grant from Robin Hood and the Robin Hood Learning + Technology Fund, this report puts forward three concrete, achievable steps to do just that: establishing a high-level statewide director of computing education; requiring all teacher preparation programs to embed computing education in their curricula; and expanding professional development in computing education for more teachers and school leaders—with a focus on ensuring that New York City is not left behind in state-level investments.

By taking action now, state leaders can help ensure that every student in New York has the opportunity to gain the skills needed to succeed in the tech-driven economy of today and tomorrow.

A range of state policies and investments will be needed to help New Yorkers get on the path to tech careers, from increasing the number of adults who can take advantage of high-quality tech training programs for adults and expanding tech apprenticeships to strengthening pathways into tech jobs for students at SUNY and CUNY. But nothing policymakers do is likely to be as important—or as effective—as strengthening computing education in the state’s public schools. As the state takes aggressive steps to become a global leader in emerging tech—including AI—it will need to move with similar urgency to ensure that New York’s public K-12 system is equipping students with the foundational digital skills needed to access these tech careers.

These critical investments in computing education should help K–12 students become computationally literate and fluent: able to understand how powerful technologies work, use them to solve real-world problems, and adapt as those tools evolve. Computing education goes far beyond learning to code—it equips students with a broader set of problem-solving and analytical skills rooted in logic, creativity, and collaboration. These foundational technology skills are more important than ever in an AI-driven era—one in which adults can no longer count on a 10-week coding bootcamp to break into the tech sector. Today, AI tools can generate code faster than any human, and many entry-level coding jobs are disappearing.

In this environment, it’s critical for New York to ensure students are exposed from the earliest grades through high school to the core concepts of computational thinking—such as how to break down complex problems, organize information, recognize patterns, and design step-by-step solutions using computers—while also building a strong foundation in digital literacy. These skills are essential not only for tech careers, but for success in nearly every well-paying job today—and to empower young people to move from being passive consumers of technology to active creators, informed decision-makers, and engaged citizens in an increasingly tech-driven world.

“In many ways, computing education is the fifth core subject area,” says Ron Summers, former executive director of New York City’s Computer Science for All initiative and the chief impact officer of Mouse.org, a nonprofit that runs tech education programs for underserved students. “It’s a language, and if you’re fluent in it, you can understand it and navigate it. If you know how to create with it, it opens so many avenues. Computational thinking is really important for a young person to develop over twelve years of their education and apply it to whatever field they want to be in.”

These opportunities abound across New York State. In Rochester, data scientists are helping healthcare systems analyze patient data to improve outcomes and reduce costs. In Buffalo, software engineers are driving innovation in advanced manufacturing—from roboticomputer science to quality control. In the Capital Region, computing skills are powering growth in cybersecurity, nanotechnology, and clean energy startups. And across upstate logisticomputer science hubs, from Syracuse to the Hudson Valley, automation and supply chain analytics are transforming how goods move—demanding a workforce fluent in digital tools.

Tech has become one of the state’s fastest-growing sectors, with employment surging 32 percent over the past decade—far outpacing the broader economy. Technology is also fueling much of the job growth in fields from finance and healthcare to education. In 2024, more than 37 percent of all job postings in New York State called for candidates with technology skills—nearly 570,000 jobs in total.6 Statewide, demand for tech skills has more than doubled since 2010—rising 120 percent across a wide range of industries. And this demand is likely to grow further as the state’s recent investments in AI and semiconductors take hold.

While New York City remains the state’s tech powerhouse, several other regions are emerging in their own right. Over the past decade, the tech sector has grown by 27 percent in Albany, 29 percent in Buffalo, and 33 percent in Westchester—all far faster than the overall economy.7 And Long Island, Syracuse, and Rochester are all home to significant clusters of tech employment.

In recent years, several key tech and computing occupations have emerged as among the fastest-growing well-paying jobs in New York—even outside of the five boroughs. For instance, the number of data scientist jobs outside New York City more than doubled since 2019, from 2,950 to 6,558—a 122 percent jump. Likewise, the number of web and UX designers surged 83 percent, topping 5,000 jobs for the first time in 2024. And New York added more than 10,000 jobs for software developers outside New York City since 2019.8

But amid this growth, the state’s tech workforce still has a long way to go before it reflects New York’s full diversity.

The state continues to experience major disparities in the tech workforce. Across New York State, just 19.2 percent of tech workers are Black or Hispanic, compared to 32 percent of the overall labor force. Women are similarly underrepresented, making up only 25.1 percent of tech jobs despite comprising 48.5 percent of the statewide workforce.9

There’s a lot that state leaders should do to close these gaps. But no strategy offers more potential to drive change at scale than an all-out effort to strengthen computing education across the K–12 public school system.

Other States Are Leaping Past New York in Computing Education

In recent years, New York has taken some important steps to expand computing education across all grade levels. Most notably, in 2020, the Board of Regents adopted the state’s first-ever Computer Science and Digital Fluency Learning Standards, setting clear expectations for teaching digital citizenship, digital fluency, and computer science from kindergarten through 12th grade. These standards are mandatory for all K-12 students to learn as of the 2024–25 school year, although they will need to be continually updated to reflect changes in technology, such as the rapid adoption of generative AI.

The state legislature has also funded the Smart Start Grant Program, which has awarded $6 million annually to 17 districts and consortia to support professional development in computer science for K–8 teachers.

Still, New York continues to lag behind many other states that are introducing important new policies to strengthen K-12 computing education. Among them:

- Massachusetts, which created a new PreK-6 digital literacy and computing license to make it easier for elementary teachers to learn about and teach computer science.

- Louisiana, which recently passed legislation that will require all elementary schools to start teaching computer science by 2027, and all teacher-training programs to add computer science lessons by 2026.

- Maryland, which created an innovative computer science ambassador program, training over 100 elementary educators in computer science to serve as advocates, mentors, and trainers within every district in the state.

- Arkansas, which became the first state to require all public schools to offer computer science, adopted a graduation requirement in computer science, and created an Office of Computer science within the state education department. Since implementing these policies, student participation has surged—from 7.2 percent in 2020–21 to 20 percent in 2023–24—including among young women, whose participation rose from 29 to 38 percent.

“In terms of where New York stands today, we are squarely in the middle,” says Sarah Henderson (Hendo) Rosenberg, senior program manager at Google.org. “While New York City saw huge momentum, particularly with the self-driven Computer Science for All (CS4All) initiative, there’s a clear need for new state policies to encourage broader adoption.”

And while New York City has led the state in efforts to bolster computing education, there is still a long way to go across the five boroughs.

In 2015, New York City made a major commitment to equity in computing education with the launch of Computer Science for All (CS4All). Since then, access to computer science instruction has expanded dramatically. According to a Center for an Urban Future analysis of data from NYC Public Schools, the number of students enrolled in computer science courses has more than tripled—from just over 54,000 students (5.5 percent) in 2016 to more than 175,000 (18.2 percent) in 2023.10

Yet participation remains far from universal, especially among students of color and those in under-resourced communities. In 2023, just 13.7 percent of Black students and 17.5 percent of Hispanic students were taking computer science classes, compared to 25 percent of Asian students and 19 percent of white students. Enrollment also varies widely by borough: while 25 percent of students in Queens and Staten Island took computer science courses, only 11.5 percent did in the Bronx. And just 19 percent of schools citywide are meeting CS4All’s equity benchmark, which calls for the demographics of students in computer science classes to reflect the school’s overall population.

Three ideas to accelerate computing education in New York State

States leading the way in computing education have done so by making it a major statewide priority—supported by strong policies, dedicated infrastructure, and sustained investment. Now is the time for New York State to join their ranks and take bold, statewide action to advance computing education. Our research recommends three concrete next steps, informed by interviews with more than 20 leaders in computing education, state and local K-12 education, and the tech sector.

They include:

- Appoint a high-level statewide director of computing education to lead policy development, coordinate implementation, and ensure accountability across New York’s education system.

- Launch a “Computing for All Teachers” initiative to embed computing education into pre-service training for all future teachers and make it a requirement—ensuring that every educator is prepared to introduce core concepts.

- Create a Smart Start 2.0 grant program to reach more teachers and school leaders with high-quality professional development in computing education—and ensuring that New York City is eligible for future funding rounds.

1. Appoint a high-level statewide director of computing education

New York lacks a dedicated, high-level leader to guide computing education across the state—a step that many states have already taken. By appointing a high-level director of computing education, Governor Hochul can help align policy, coordinate investments, and ensure accountability across schools, districts, and agencies.

Dozens of states have recognized the value of a dedicated statewide leader of computing education efforts and created a position in recent years. As of 2024, more than 40 U.S. states have appointed a supervisor of computing education—including, in theory, New York. However, the position’s role and function vary widely across states, which leads to significantly different levels of authority, influence, and impact.

In New York, the position is an associate role within the New York State Department of Education’s Career and Technical Education (CTE) division. While creating this role is an important first step, it is smaller in scope and more siloed than that of other states with a true statewide director of computing education.

By comparison, several other states have created an elevated role that is better positioned to drive impact. In Arkansas, the state director of computer science education leads a dedicated Office of Computer Science and reports directly to senior education leadership. Tennessee houses its computer science director within the academic affairs division, giving the role broad authority to coordinate K–12 curriculum, teacher training, and partnerships across agencies. And in Maryland, the state has established a dedicated Computer Science Supervisor within the Department of Education and created the Maryland Center for Computing Education to support statewide implementation, align computer science pathways with workforce needs, and expand access to high-quality computing instruction.

New York’s approach has nested responsibility for computing education within the state’s Career and Technical Education (CTE) team, which focuses on technical instruction that can prepare high school graduates for job training programs and careers. But while CTE is an important part of computing education, experts say that much more is needed to treat computing as a core subject area for all students and integrate it across the K-12 curriculum.

Without high-level statewide leadership, computer science too often remains siloed as an elective—limiting opportunities to build sequenced learning across grades, integrate computing into other subject areas, and connect K–12 education to college and career pathways. A dedicated director can help shift this dynamic by ensuring that computer science and computational thinking are not only treated as technical subjects, but are integrated across disciplines—supporting learning in math, science, social studies, and beyond. Integration is key to both universal access and real-world relevance, and none of this is possible without trained and supported educators.

“If you really want people to take computer science seriously, it has to be thought of as a curriculum area, a content area,” says Elissa Hozore, the former Maryland state supervisor for computer science. “And how you want to make that work in collaboration with math and science, that’s fine, but it has to be seen for the value of itself. It can’t just be stuck in with something else. Then it won’t happen.”

Paula Moore agrees. She’s served as the digital literacy and computer science content specialist in Massachusetts since 2020. She says Massachusetts has been an early leader in computing education policy in large part thanks to having a dedicated computer science team in the state education department since 2016.

“If New York State is committed to moving computer science education forward, there needs to be a person who understands the computer science landscape and content,” Moore says.

Having a dedicated director of computing education would also provide a point person within the state to connect with and forge relationships with other state computing supervisors. Currently, 30 states and the territory of Puerto Rico participate in the Expanding Computing Education Pathways (ECEP) Alliance, a national network that supports state-level computing education reforms. New York is notably absent from this alliance.

These relationships foster not only shared knowledge but also collaborative initiatives that advance computing education. For example, state computing supervisors in Washington, Oregon, and Idaho have secured National Science Foundation funding to research ways to strengthen elementary pathways in computer science for students in rural, low-income communities. Without a dedicated state supervisor and participation in networks like ECEP, New York risks missing out on opportunities to collaborate with other states and to bring innovative models back to its own classrooms. Likewise, the state is missing out on opportunities to collaborate with other states on tracking and monitoring progress and aligning data-gathering best practices—work that ECEP facilitates nationally.

Perhaps most importantly, a high-level state director could help marshal the state’s resources to pursue the next phase of computing education policy—such as requiring all schools to offer high-quality computing classes or adopting a statewide graduation requirement. But before any requirement can be implemented, schools will need the infrastructure, trained educators, and support systems in place to ensure equitable access. Reaching these goals will require far greater coordination among public higher education institutions, the State Education Department, school districts, employers, and philanthropy. An empowered director could play a pivotal role in aligning these efforts and laying the groundwork for long-term success.

2. Launch a “Computing for All Teachers” initiative to expand pre-service training for teachers—and make it a requirement.

None of the investments New York makes in computing education will succeed unless there’s a teaching force prepared to bring it to every student, from kindergarten through high school. Dramatically expanding access to computing education will require more than offering standalone courses or electives—it will take integrating computational thinking across subjects and grade levels. To get there, New York will need to prepare thousands of future teachers with the skills, knowledge, and confidence to incorporate computing into their everyday pedagogy.

Yet the state currently lacks any policy to ensure that all teacher candidates gain exposure to computing education. There is no statewide expectation that new teachers—whether they go on to teach elementary school, math, science, or even English—are equipped to teach students how to think computationally or understand emerging technologies like AI. One clear step forward would be to make computing education a pre-service requirement for all future teachers in New York—a smart step that six other states have already taken. Governor Hochul can lead the way by establishing this as a policy goal, with the requirement established though the Board of Regents. And the State Legislature can support this effort by funding a “Computing For All Teachers” initiative in the state budget.

“Similar to the momentum to build a future-ready workforce, we need to equally invest in building a teaching workforce equipped to prepare students for careers of tomorrow,” says Rosenberg of Google.org.

New York already has a model for how to build a pipeline of computing-ready teachers—in its own backyard. The City University of New York (CUNY), which prepares about one-third of all new teachers hired by New York City Public Schools, launched the Computing Integrated Teacher Education (CITE) initiative in 2020 to help future educators integrate computing and digital literacy into their classrooms.

Since its launch, CITE has trained more than 6,500 teacher candidates and roughly one-third of faculty across CUNY’s education schools. But with full implementation in just one of CUNY’s 16 colleges, the initiative is still only reaching about half of teacher education students. Scaling CITE across CUNY could prepare over 8,000 new computing-ready teachers within five years—reaching more than 40,000 students annually in NYC alone.

But even a fully scaled CITE initiative would only begin to meet the demand. Each year, New York City hires approximately 4,500 new teachers, and across the state, more than 215,000 educators serve over 2.4 million students. Reaching all classrooms with high-quality computing education will require preparing thousands more teachers annually with the skills and confidence to integrate computing into a wide range of subjects and grade levels.

“It’s nuts that this is still not part of teacher preparation programs,” says Diane Levitt, senior director of K-12 education for Cornell Tech. “We need to figure something out, because we can’t just retool our people. It’s not a good use of resources.”

It’s no wonder that even school leaders eager to bring computing into their classrooms face challenges—due not only to a shortage of computer science specialists, but also to the lack of elementary teachers, subject-area educators, and instructional technology staff equipped to integrate computing concepts into the classroom and coach other teachers. (In states like Massachusetts, instructional technology specialists are already playing a key role in supporting this work in schools.)

“Computer science education is different from the issues facing math and science educators— subjects where students have the content every year from elementary school, and where the teachers themselves have had training in the content since elementary,” says Moore, the Massachusetts computer science content specialist. “Computer science teachers do not have that benefit and need to be recruited, developed, and retained in different ways than other teachers.”

The bottom line is that building New York State’s capacity to expand computing classes and boost participation will require a major new effort to prepare the teachers the state needs. Training pre-service teachers is both cost-effective for schools and ensures students don’t lose valuable learning time while teachers are retrained. It also leads to more meaningful classroom experiences—where students actively engage with technology, like programming a basic game to reinforce the concept of fractions, rather than just playing a math game on a tablet.

“I get calls all the time from principals looking for computer science teachers because the city and state don’t have a recruitment plan for computer science teachers,” says Summers of Mouse.org.

If the state stepped in to support CITE, it would certainly make a dent. But CITE alone is not enough. That’s why the state should make it a priority to fund teacher training programs to prepare all future teachers not only at CUNY but also at the State University of New York (SUNY), where 5,000 students graduate with teaching degrees each year. SUNY also provides nearly one-quarter of New York’s K-12 teachers.

“I think everyone in teacher education sees the potential and the opportunity and the need, but they aren’t sure how to get there,” says Aankit Patel, University Dean for Technology and Computer & Information Sciences at CUNY and former director of CITE. “There are a lot of teachers coming out of SUNY and they should all have these skills. Every discipline needs these types of skills.”

In addition to training pre-service teachers, New York could also leverage this initiative to support current teachers. In New York City, only about 4 percent of teachers have received computer science-related professional learning sessions through CS4All as of 2024,11 with most schools having just one or two trained teachers.12

The state can address this problem by establishing a microcredential for computing education—similar to one in the science of reading New York launched last year. In addition to $10 million allocated by the legislature to offer cost-free training, the state also established science of reading microcredentialing programs at SUNY New Paltz and the University of Buffalo Graduate School of Education.

This computing microcredential could also play a vital role in expanding the number of teachers equipped to bring computing into the classroom—beyond those pursuing full certification. New York’s newly announced requirement for computer science teachers to hold a computer science certificate is an important step toward ensuring quality and consistency in advanced computer science instruction. But to truly scale computing education, the state will also need to prepare a much larger pool of teachers—with the foundational skills to integrate computing concepts, foster computational thinking, and help students navigate emerging technologies like AI across subjects and grade levels. A combination of a pre-service requirement and a targeted microcredential could help build that broader base of computing-literate educators.

3. Create a Smart Start 2.0 grant program—and ensure that New York City is included.

One of the clear bright spots in New York’s efforts to expand computing education is the Smart Start Grant program. Since launching in 2021, it has awarded $6 million annually to 17 school districts statewide to develop and share innovative models for professional development in computer science and digital literacy for K–8 teachers.

But New York City—the state’s largest school district and home to nearly half of its public school students—was not among the grant recipients. To address this, Governor Hochul and the State Legislature should launch a second round of funding—Smart Start 2.0—with increased resources of $12 million per year; a commitment to expanding participation, including explicit support for New York City Public Schools; and eligibility across all of K-12 public education.

Despite significant progress over the past decade, New York City’s schools need more support to close the gap in computing education access and participation. A recent report from the Research Alliance for New York City Schools highlights why: although more than 3,000 teachers across 1,000 schools have completed CS4All training, that’s still just a fraction of the city’s teaching force. And even among those trained, only 68 percent went on to implement computing in the classroom—held back by structural barriers like rigid schedules, limited prep time, and insufficient support from school leaders. Given both the sheer scale of the system and the deep equity gaps that persist across schools and neighborhoods, it will be impossible to move the needle on statewide access or opportunity without a much larger focus on New York City. Smart Start 2.0 offers a clear opportunity to tackle these challenges head-on—with targeted professional development for teachers and school leaders, and accountability for moving from training to implementation.

In the past, the state has clearly shown a willingness to invest in computing in schools. It began with the Smart Schools Bond Act, which—after getting approval by New York State voters in 2014—authorized $2 billion in bonds to improve educational technology and infrastructure in public schools.

The Smart Start program builds on a foundation laid by the Smart Schools Bond Act, approved by voters in 2014, which authorized $2 billion to improve educational technology and infrastructure. Crucially, the state recognized that technology alone wouldn’t move the needle without investing in teachers. Smart Start filled that gap—providing thousands of educators with the training needed to integrate computing and digital literacy into daily instruction.

Since its inception, the program has supported professional development for more than 7,000 K–8 teachers across over 500 schools. And the results speak for themselves.

In Huntington Union Free School District on Long Island, one of the original grantees, computing education has expanded from a single high school computer science teacher to a full K–12 experience. Today, all students take a foundational computing course before graduation. The district now employs three computer science teachers, up from just one before the grant, and offers AP-level courses as well.

“The first year or two was rough because no one knew where we were going with the digital literacy standards,” says Teresa Grossane, Huntington’s director of K–12 math and computer science. “The first step was understanding the standards and the reason for them, and getting buy-in from teachers, which was hard. The first thing teachers say is ‘Where do I do this? How do I teach this?’”

Thanks to Smart Start, Grossane and her team had the time and capacity to figure it out. Over the first two years, they trained library specialists and ten classroom teachers annually, created a K–8 scope and sequence, and built activities to support the standards—work that eventually reached the broader staff.

More districts deserve this opportunity. But with the Smart Start grant set to expire in 2026, the state should renew and expand it.

“Continuing it, expanding it, making it more available to others, I think is important,” says Jeffrey Matteson, senior deputy commissioner for education policy at the New York State Education Department. “This funding, these grants that are tied to certain activities, they really do move the needle.”

The decision, however, lies with state elected officials. NYSED can propose a budget, which is then reviewed by the Board of Regents, but it is ultimately enacted by the governor and the legislature. Without sustained support, Smart Start could be cut—or fail to reach the scale New York’s students need. And New York City runs the risk of being left out permanently.

New York City’s exclusion from the first round was not due to a lack of effort. The city submitted proposals from each borough, but the application structure required submissions from individual Community School Districts (CSDs) or consortiums of two or more—an awkward fit for NYC’s centralized system. For Smart Start 2.0, the state should amend its application process to better accommodate New York City’s scale and structure.

Alternatively, New York City could adapt its approach by submitting district-level applications. Tom O’Connell of CSForNY believes this would improve the city’s chances.

"If New York City were able to apply for the Smart Start Grants this time through their community districts, I believe that they would be competitive applications that would likely result in meaningful funding for the district,” O’Connell says.

There’s evidence that this strategy can work. Looking at NYSED’s Learning Technology Grant—which awards $3.2 million annually for educational technology professional development—several New York City districts have successfully won funding.

For Smart Start 2.0, the state should not only encourage New York City districts to apply but actively support applications from high-need areas identified through CS4All data—and New York City’s Albany delegation should support this initiative both in the budget and at the district level. These efforts should be backed by district superintendents to ensure coordination and oversight.

“Districts care about computing education, but they’re not getting the signals that they need,” says Tom O’Connell of CSForNY. “They’re not seeing an interest from the state in measuring what’s happening in computing education. To meet the opportunity, it takes the state leading the way and a real reimagining from the top.”

Endnotes

1. “2024 State of Computer Science Education,” Hannah Weissman, Maggie Glennon, Bryan Twarek, Catherine Tabor, Sarah Dunton, Dr. Josh Childs, and Dr. Nicole Martin, Code.org, CSTA, ECEP Alliance, 2024, https://advocacy.code.org/stateofcs

2. Center for an Urban Future analysis of data from the Code.org Computer Science Access Report, 2024.

3. Center for an Urban Future analysis of data from the 2023 New York City Department of Education Local Law 177 report.

4. Computer Science Access Report Data, Code.org, 2024.

5. Weissman et al.

6. Center for an Urban Future analysis of data from labor market analytics firm Lightcast.

7. Center for an Urban Future analysis of Lightcast data.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid.

10. Center for an Urban Future analysis of New York City Department of Education Local Law 177 data from 2016 and 2023.

11. Fancsali et al.

12. CUF

.png)