As part of its New York Works jobs plan, the de Blasio administration hopes to add at least 4,000 good jobs by expanding logistics and distribution networks around the five boroughs. The initiative, dubbed FreightNYC, is right to focus on freight—an important source of middle-class jobs—but it does not include New York’s air cargo sector, one of the largest sources of freight jobs across the five boroughs and a sector increasingly in need of support.

With global trade again on the rise, nearly every major airport in the country is experiencing increases in air cargo volumes. But New York’s dominant air cargo hub, JFK International Airport, is trending in the opposite direction.

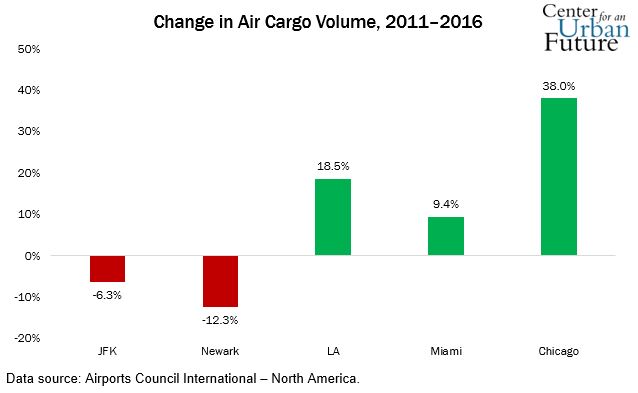

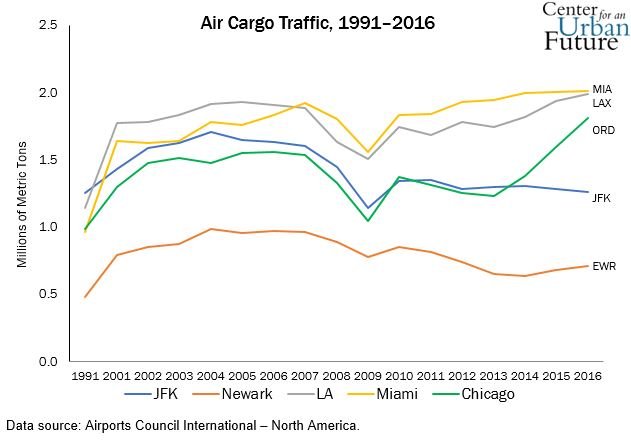

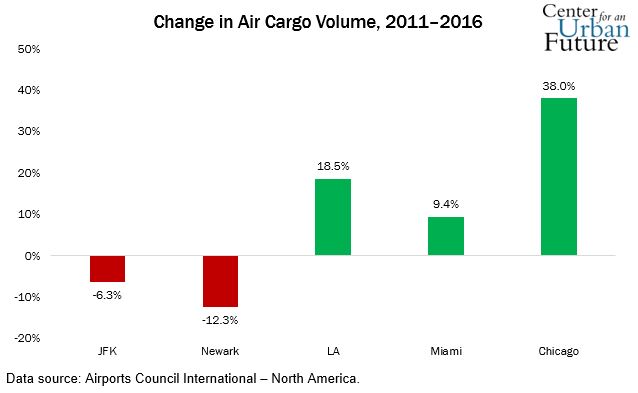

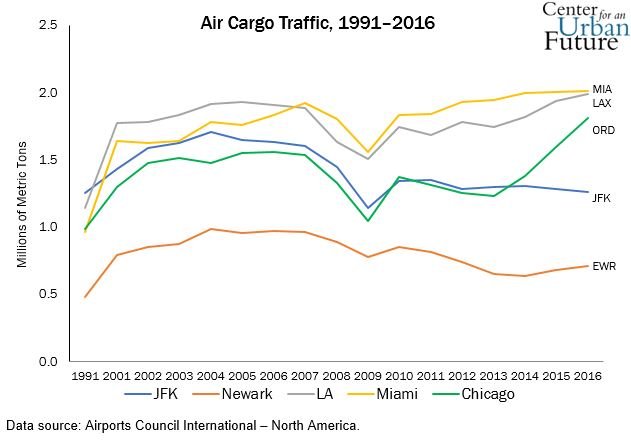

As this new analysis shows, the city’s once dominant air cargo sector is rapidly losing market share to competitors across the country. Kennedy handled more cargo than any other airport in the world until 1990. Now, JFK has fallen to seventh in the United States.1 Over the past five years, cargo volumes at JFK have declined more than 6 percent, while rising 9.4 percent at Miami International Airport, 18.5 percent at Los Angeles International Airport, and a whopping 38 percent at Chicago O’Hare.2

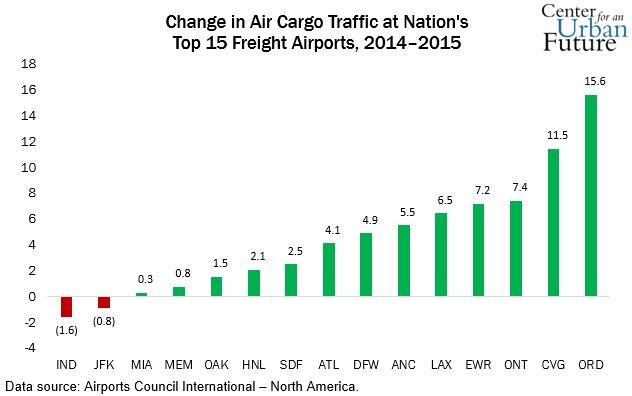

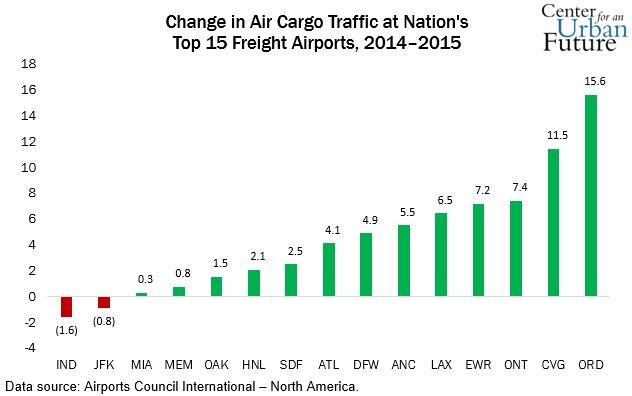

Between 2014 and 2015—the most recent year for which data is available for all U.S. airports—only two of the nation’s 15 largest airports experienced a decline in air cargo traffic: JFK and Indianapolis International Airport.

Despite the recent declines at JFK, there is ample reason to believe that—with the right support—New York’s air cargo sector has significant potential for growth in the decades ahead. Air cargo movements in the United States and internationally are expected to grow at a significant clip over the next two decades. According to the 2017‒2037 Aerospace Forecasts from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), air cargo movements in and out of U.S. airports are projected to increase at an average rate of 3.1 percent per year through 2037. Domestic cargo movements are forecast to increase at an average annual rate of 1.3 percent, while international cargo traffic—which is a particular strength for JFK—is forecast to grow an average of 3.8 percent annually.

If JFK could capture a proportional share of this growth, it would mean hundreds if not thousands of new middle-class jobs for New Yorkers.

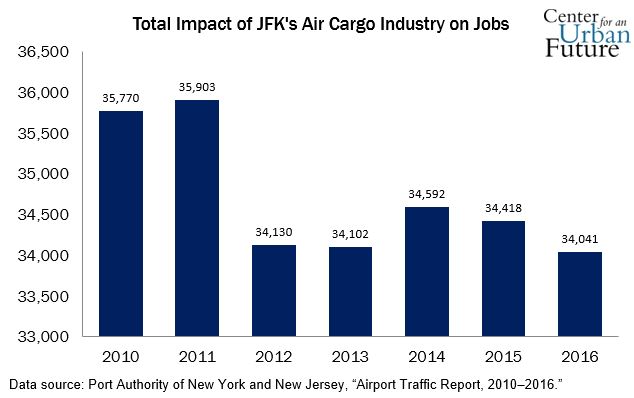

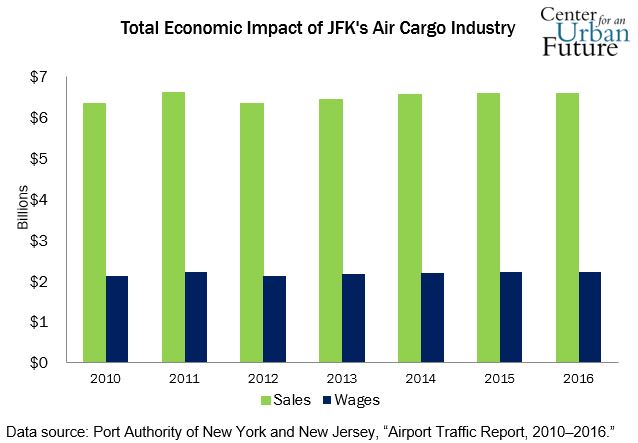

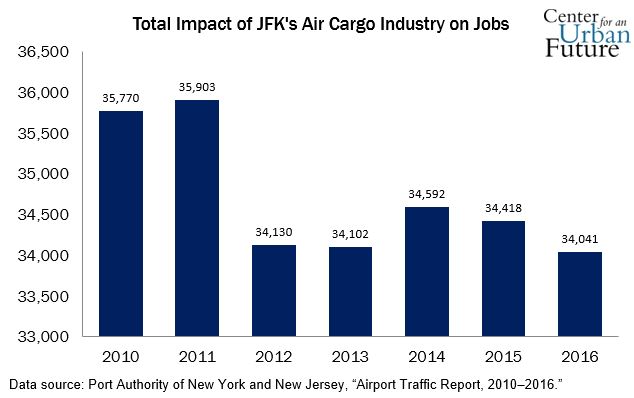

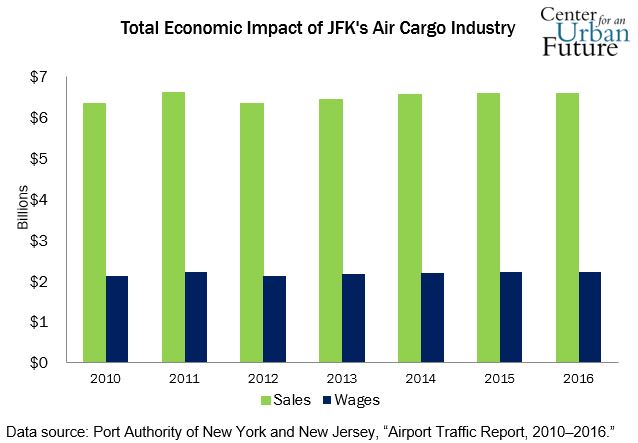

Air cargo is already a critical source of good jobs in the city. JFK’s air cargo industry sustains some 34,000 jobs citywide, both on-airport and in off-airport warehouses, distribution facilities, and regional suppliers, according to the Port Authority’s count.3 Of these, more than 15,000 jobs are at the airport itself, comprising roughly 20 percent of JFK's total on-airport workforce.4 Air cargo workers earn on average more than $44,000 annually, with pathways to supervisory roles and higher incomes.5 The majority of these middle-wage jobs are accessible to most New Yorkers, with roughly four out of five requiring only a high school diploma. In addition, thousands of ancillary jobs stretch across the region—that fresh tuna for tonight’s sushi or pasta may have just flown in from Tokyo or Palermo. JFK’s cargo industry generated $6.5 billion in sales last year, underscoring the economic impact of this vital global link.

The Center for an Urban Future (CUF) has found several key trends reshaping the air cargo industry locally and nationally:

- Over past five years, air cargo tonnage at JFK has declined 6.3 percent, to 1,264,187 metric tons from 1,348,992 in 2011. Cargo volume is down 26 percent from 2004, when tonnage peaked at 1,706,468 tons.

- The total impact of JFK’s air cargo industry on sales has fallen 31 percent since 2004, when adjusted for inflation, from a high of $7.4 billion ($9.4 billion in 2016 dollars).

- During the same five-year period, tonnage has risen 9.4 percent at Miami International, to 2,014,205; 18.5 percent at LAX, to 1,993,308; and 38 percent at O’Hare, to 1,810,134.

- Even Newark Liberty International, where cargo volume declined 12.3 percent over past five years, has seen some growth since 2014. The nation’s 12th busiest cargo destination, it gained nearly 74,000 tons the past two years for a total of 713,469.

- Nationally, air cargo tonnage rose 6 percent among the top 50 airports between 2011 and 2015. Much of the growth has been among the top five airports, which underscores how much JFK is losing out.

- The only recent year of cargo growth at JFK was between 2009 and 2010, when there was a steep decline and subsequent recovery as a result of the Great Recession. Tonnage fell 21 percent in 2009, to 1,144,894 before recovering 17 percent the following year. It grew less than 1 percent in 2011 and has been falling ever since.

- The impact on jobs at the airport has, unsurprisingly, paralleled the decline in cargo, according to Port Authority surveys, although cargo volume is not the only reason for the decrease. The total economic impact of JFK’s air cargo industry sustained 34,041 jobs in 2016, down from 35,903 in 2011, a decline of 5.5 percent. The number of jobs peaked at 46,120 in 2004, meaning there are 26 percent fewer jobs today.

As the Center has detailed in previous reports about the city’s air cargo industry, the main challenge facing the industry-—by a long shot-—is road access to Kennedy Airport. Only one highway route, the Van Wyck Expressway, exists to bring trucks from JFK to Manhattan and the highways beyond, and that route is plagued by chronic congestion. Trucks picking up cargo at the airport often sit for hours on the Van Wyck on their way out of the city.

CUF warned as far back as 2000 that rival airports could overtake JFK, and none more so than O'Hare International Airport in Chicago. For years, the Second City had gained cargo traffic but still lagged behind New York, but in 2013 that began to change. O’Hare broke ground on a major 65-acre expansion to its cargo facilities, and though it will not be completed until 2021, the $222 million investment may have contributed to an explosion of traffic there. O’Hare has not only surpassed New York, but it is on track to overtake Los Angeles and Miami, as well.

Over the years, CUF has put forth a number of recommendations for city and state economic development officials, as well as the Port Authority, to address the challenges facing New York’s air cargo sector, including:

Improve traffic flow on the Van Wyck Expressway. Among other strategies, the Center has suggested closing one or two entrance ramps on the Van Wyck Expressway during certain peak hours. Doing so would help put an end to the common practice, used mostly by taxis, of driving on the service road to get off and on the Van Wyck—a ritual that slows down traffic on the highway.

Open the Belt Parkway to commercial vans. Currently, the Belt Parkway prohibits all commercial vehicles, from 53-foot trucks to the commercial vans often used by overnight delivery companies. The Belt would provide a much faster alternative route for companies delivering goods to offices in lower Manhattan, and could possibly enable Kennedy to recapture some of the lost overnight freight companies that shifted to Newark Airport over the past two decades. This change would not open the door for trucks to operate on the parkway, since the low height of bridges over the Belt simply makes it impossible for trucks to pass.

Modernize aging cargo facilities at JFK. To keep airlines from moving their freight business to other airports, the Port Authority should address the serious shortage of affordable, modern cargo facilities at Kennedy. According to our 2013 Caution Ahead report, JFK’s air cargo facilities are 40 years old on average, with 63 percent of cargo space considered “non-viable,” or unfit for modern screening, storage, and distribution.

Modernize the air traffic control system. To ensure that New York’s airports can handle anticipated growth, the FAA and Congress need to approve—and fund—a strategy to address gridlock in the airspace above New York and reduce incessant airline delays. President Trump and Congress can make this happen by fully funding the $35 billion that it would take to implement NextGen, a longstanding plan to convert today’s archaic air traffic control system to a system that uses satellite navigation GPS technology. Meanwhile, the Port Authority should give serious consideration to other ideas for expanding JFK’s capacity, including efforts to reconfigure or lengthen its runways, steps that were taken in recent years at O’Hare Airport in Chicago to reduce delays and boost capacity.

As the de Blasio administration embarks on its FreightNYC initiative, it should take a close look at these and other policy solutions for strengthening New York’s air cargo sector. Although the city does not have direct control over the airport itself, the administration could help address the ground access problems, and it could also make take steps to improve the many air cargo warehouses and logistics operations just off airport in Springfield Gardens and Jamaica.

Clearly, Governor Cuomo and the Port Authority also have significant responsibility for boosting New York’s air cargo sector. To his credit, in a January 2017 State of the State speech the governor announced a series of new investments to expand JFK that included specific proposals to improve traffic flow on the Van Wyck Expressway. And while that speech about the $10 billion overhaul planned for JFK did not specifically mention air cargo, an accompanying report prepared by a state commission called “for new, consolidated, and expanded cargo facilities.”

If the city, state, and Port Authority remain on the current path, the air cargo industry will likely continue its flight to other locales—and miss out on an opportunity to preserve and grow middle class jobs. But with a burst of renewed and sustained attention in City Hall and Albany, JFK could finally begin to turn around its recent air cargo slide.

1. In this brief, all data on air cargo traffic is from Airports Council International – North America, except where noted.

2. Data on air cargo traffic in 2016 is from Airports Council International and is considered preliminary.

3. Estimates of the total economic impact of JFK’s air cargo industry on employment are from the Port Authority’s “2016 Airport Traffic Report,” https://www.panynj.gov/airports/pdf-traffic/ATR2016.pdf.

4. Data from NYCEDC’s “JFK Air Cargo Study,” January 2013, https://www.nycedc.com/resource/jfk-air-cargo-study. On-airport employment figures represent individuals who require airport security badges to work at the airport, so the total number of on-airport cargo employees is likely to be more than 15,000.

5. Wage data from the New York State Department of Labor, Long-Term Occupational Employment Projections, 2014‒2024.

Photo credit: Skyler Smith/Unspash