In little more than a decade, Brooklyn has emerged as a national leader in the innovation economy. The borough’s recent growth in tech start-ups, creative companies, and innovative manufacturers is outpacing the rest of New York City and many other leading cities nationwide. This runaway success in the innovation industries has been a boon to both Brooklyn and New York City, adding thousands of new, well-paying jobs across Brooklyn, diversifying the borough’s economy, and giving Brooklyn an important competitive advantage in a part of the economy that is expected to grow significantly in the years ahead.

But despite its success, Brooklyn still has a ways to go to fully realize its vast potential in the innovation economy. For instance, although a disproportionate share of people working in tech and creative fields in New York City live in Brooklyn, surprisingly few large innovation companies have relocated to the borough. And though Brooklyn is teeming with small and mid-sized start-ups, many of them have struggled to scale up while remaining in the borough.

As this report details, a handful of challenges—from a lack of good intra-borough transit options to an insufficient amount of affordable office space for growing companies—are threatening to constrain Brooklyn’s future growth in the innovation economy.

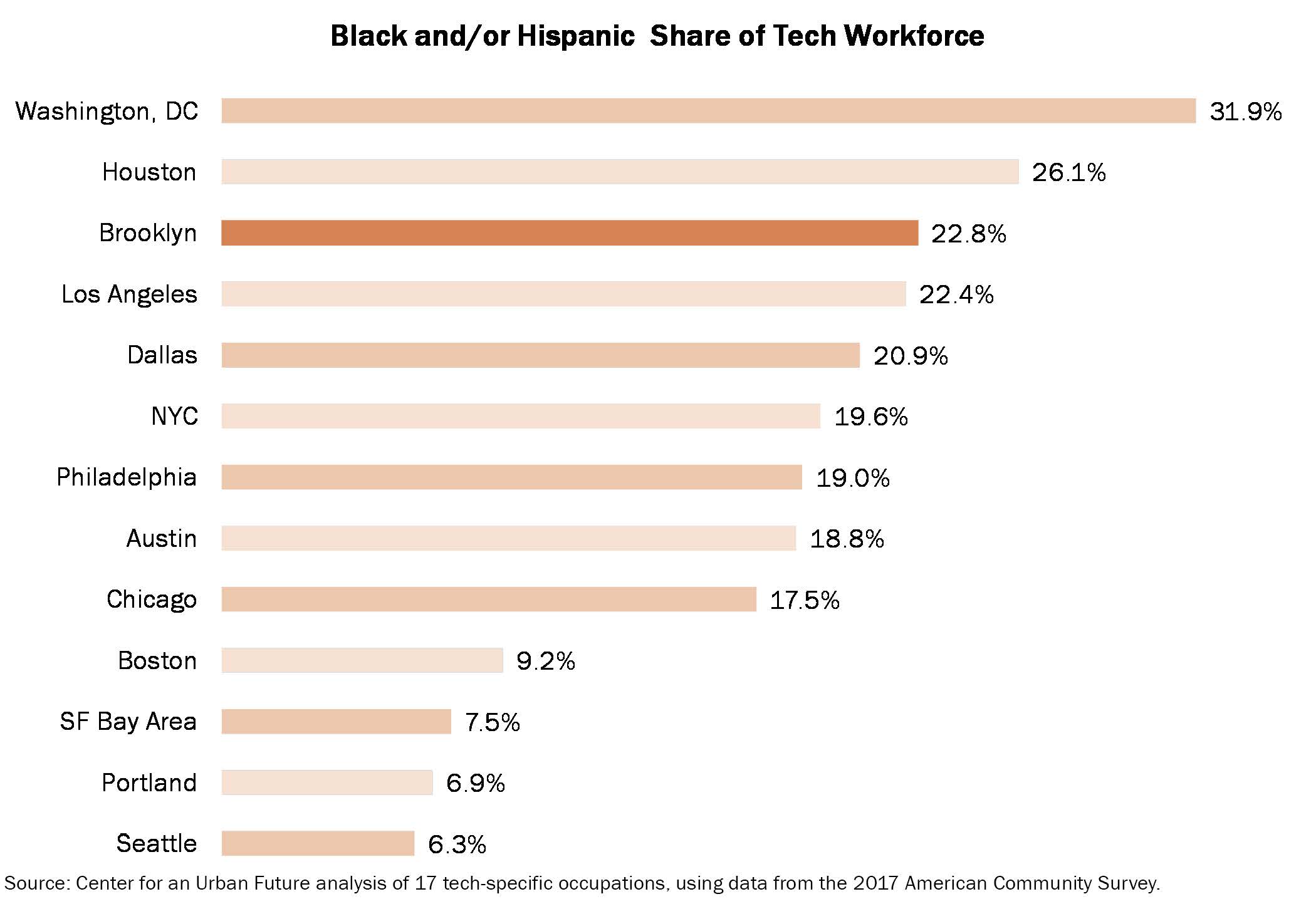

At the same time, Brooklyn has work to do to make sure that the growth occurring in its innovation industries is more inclusive. While our research finds that the share of black and Hispanic workers in Brooklyn’s tech workforce is notably higher than in many other major tech hubs such as Boston, San Francisco, and Seattle, significantly more progress is needed in expanding access to the good jobs being created in Brooklyn’s innovation economy.

Although the borough boasts some of the city’s best schools, colleges, and workforce development organizations, our research finds that Brooklyn is still lacking in education and training programs that help expose Brooklyn residents to career pathways in the innovation economy and prepare Brooklynites for these jobs.

There is much at stake for Brooklyn to address these challenges and build a larger and more inclusive innovation economy. Doing so could mean thousands of additional well-paying jobs for residents across the borough in the years ahead, a welcome prospect at a time when a disproportionate share of the job growth nationally and in New York has been in low-wage industries—and when a new wave of automation will likely cause some good jobs to disappear.

This report outlines the key obstacles to growing Brooklyn’s innovation economy and creating new pathways into these jobs—and it puts forth a series of achievable recommendations to overcome these challenges and realize the borough’s immense potential to develop a larger and more inclusive innovation economy. Researched and written by the Center for an Urban Future and produced in partnership with Downtown Brooklyn Partnership, Dumbo Improvement District, Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corporation, and Industry City, it is informed by interviews with more than 50 company founders, investors, educators, workforce development organizations, real estate developers, and economic development officials in Brooklyn, as well as more than a dozen experts working in relevant fields outside of the city. It builds on the Center’s June 2019 data brief, Brooklyn’s Growing Innovation Economy, which provided a new level of detail on the diverse mix of tech startups, creative companies, and entrepreneurial makers and manufacturers that are flourishing in Brooklyn today.

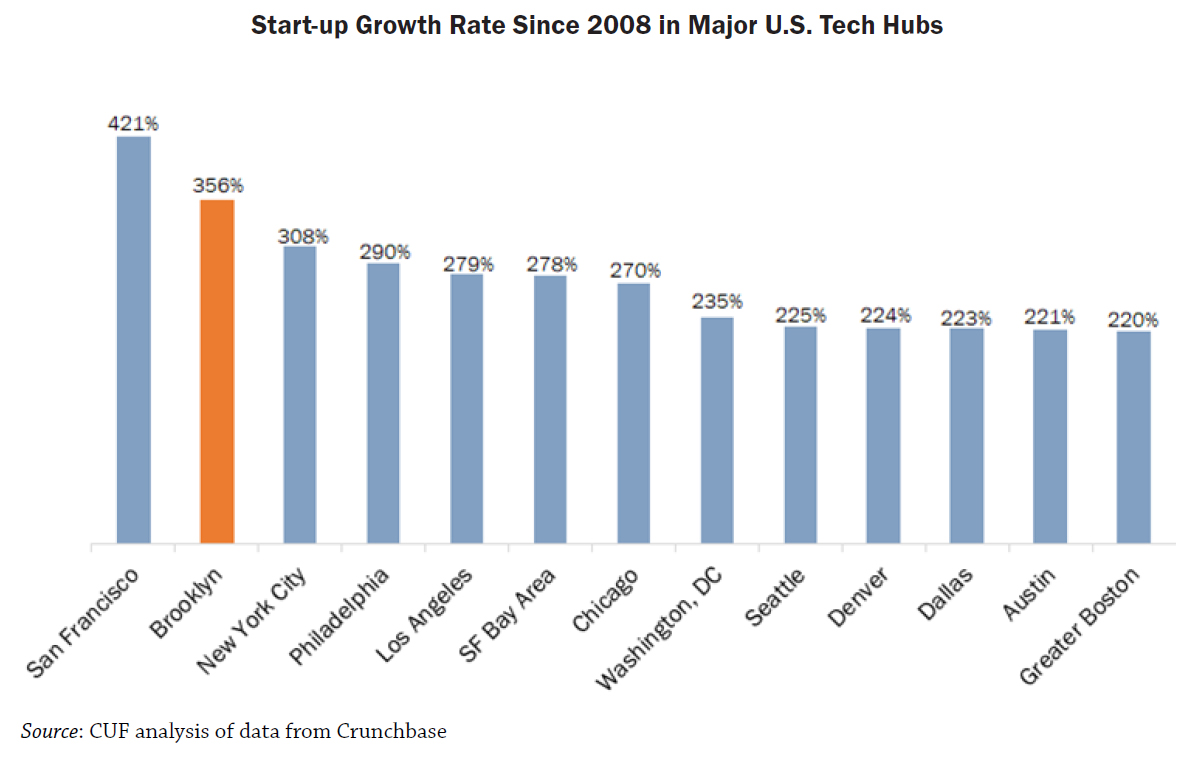

Our research shows that Brooklyn is one of just a handful of regions across the country to capture a significant share of the growth occurring in the innovation economy—a set of industries fueled by technology, creativity, and invention that is driving much of the nation’s high-wage job gains. In 2018, forinstance, Brooklyn was home to 1,205 tech-powered start-ups—a remarkable increase from 264 start-ups a decade ago. Additionally, employment in Brooklyn’s creative industries surged by 155 percent over the past decade, nearly ten times the growth rate of Manhattan. And Brooklyn’s manufacturing sector has significantly outperformed the city’s, with much of the growth coming from a new generation of companies at the intersection of manufacturing, technology, and design.

Nearly everyone we interviewed said that Brooklyn is well positioned for even more growth in the core industries of the innovation economy. Today, Brooklyn has a strong foundation of tech start-ups, creative companies, advanced manufacturers, and entrepreneurial makers that either started in the borough or have been planting roots here for several years. The borough is home to an unmatched pool of tech and creative talent. It also has a more diverse innovation economy workforce than most other cities, a point of strength at a time when many employers are understandably feeling pressure to diversify their workforces. And Brooklyn benefits from a robust innovation infrastructure—with vital R&D centers like NYU Tandon School of Engineering and New Lab, and roughly 60 incubators and co-working spaces.

- Transit Gaps – With more subway stations than any other borough, Brooklyn’s expansive transit network is one of the borough’s greatest assets. Yet in our interviews with innovation economy leaders, transit was also one of the most frequently cited obstacles to the growth of the borough’s innovation economy. In particular, our research found growing concerns about two types of transit gaps:

- Limited intra-borough transit connections. Although there is a large tech and creative workforce living in Williamsburg, Greenpoint, and Bushwick, interviews suggest that many opt to commute to jobs in Manhattan because of the lack of efficient transit options connecting North Brooklyn to innovation economy job centers in Dumbo, Downtown Brooklyn, and Sunset Park.

- Long commutes from the surrounding region. Large innovation companies are often deterred from moving to Brooklyn because they need to draw talent from all over the region but find Brooklyn lacking in easy transit commutes from New Jersey, Westchester, and even Long Island. Several company founders cited the lack of a direct ferry connection between New Jersey and Brooklyn, while others noted that employees commuting from Westchester are turned off by the additional 20- to 45-minute commute time to Brooklyn after arriving at Grand Central Terminal. And at a time when companies face fierce competition for top talent, these commuting challenges become a major factor in siting decisions.

- Space Constraints – A second key challenge raised in the majority of our interviews is the limited supply of affordable commercial space in neighborhoods across the borough that are most attractive for innovation companies. Although innovation companies are certainly not the only ones facing real estate obstacles in Brooklyn today, we heard about two specific space-related challenges that have become a major barrier to the borough’s growth in the innovation economy:

- Next-stage space for start-ups to grow. Brooklyn has no shortage of incubators, but start-ups outgrowing those facilities often find it difficult to locate other affordable spaces within the borough—especially in the neighborhoods that are seen as most attractive by innovation companies. “I have seen companies start in Brooklyn or consider Brooklyn, but they couldn’t get the right size space for around 25 to 40 people,” says Charlie O’Donnell, founder of Brooklyn Bridge Ventures, a seed stage investment fund. “We have to make sure these emerging companies stay and grow here,” adds Sayar Lonial, the associate dean for communications and public affairs at NYU Tandon, who says that companies coming out of NYU’s incubators often struggle to find the 500 to 5,000 square foot space with flexible leases they need as they grow.

- New commercial space in high-demand neighborhoods. Despite extremely low commercial vacancy rates, relatively few new office spaces are being built in Brooklyn. This is likely the result of zoning rules that give preference to residential development and create few incentives for developers to build commercial projects. At the same time, several of the most in-demand neighborhoods are home to commercial buildings that have clear potential to house innovation companies but are being used instead for municipal uses—from the tow pound at the Brooklyn Navy Yard to the Board of Election storage facility in Downtown Brooklyn—and for self-storage.

In addition, our research identified a range of other challenges that could inhibit the growth of theinnovation economy in Brooklyn, if left unaddressed.

These include:

- Talent shortages, particularly for engineers, software and hardware developers, UX designers,data scientists, cybersecurity specialists, and other highly specialized workers.

- Rising housing costs, which could make it difficult for the borough to hold onto its greatest competitive advantage in the innovation economy: its highly educated and entrepreneurial workforce.

- Concerns about Brooklyn’s ability to maintain its creative edge amid rising costs and the proliferation of national chains.

- Questions about the future of the Relocation and Employment Assistance Program (REAP), which will terminate next year if it is not reauthorized in Albany. REAP provides income tax credits of up to $3,000 per employee for companies relocating jobs to Brooklyn (and the other three boroughs outside of Manhattan) from outside the city or below 96th Street in Manhattan. According to our research, many of the innovation companies based in Brooklyn today would not have relocated to the borough without the REAP incentives.

While Brooklyn has more to do to keep its innovation economy growing, it also will need to take steps to ensure that a lot more residents from Brooklyn’s lowerincome communities are able to access the well-paying innovation industry jobs being created in the borough.

Jobs in the borough’s innovation economy have the potential to become the middle-income career paths of the future, transforming the lives of New Yorkers from lower-income backgrounds. But to realize this potential, city and local leaders needs to make significant strides in equipping Brooklynites with the skills and experience necessary to succeed in the innovation economy. Indeed, it was abundantly clearfrom our site visits and interviews that Brooklyn’s innovation economy workforce does not adequately reflect the borough’s diversity.

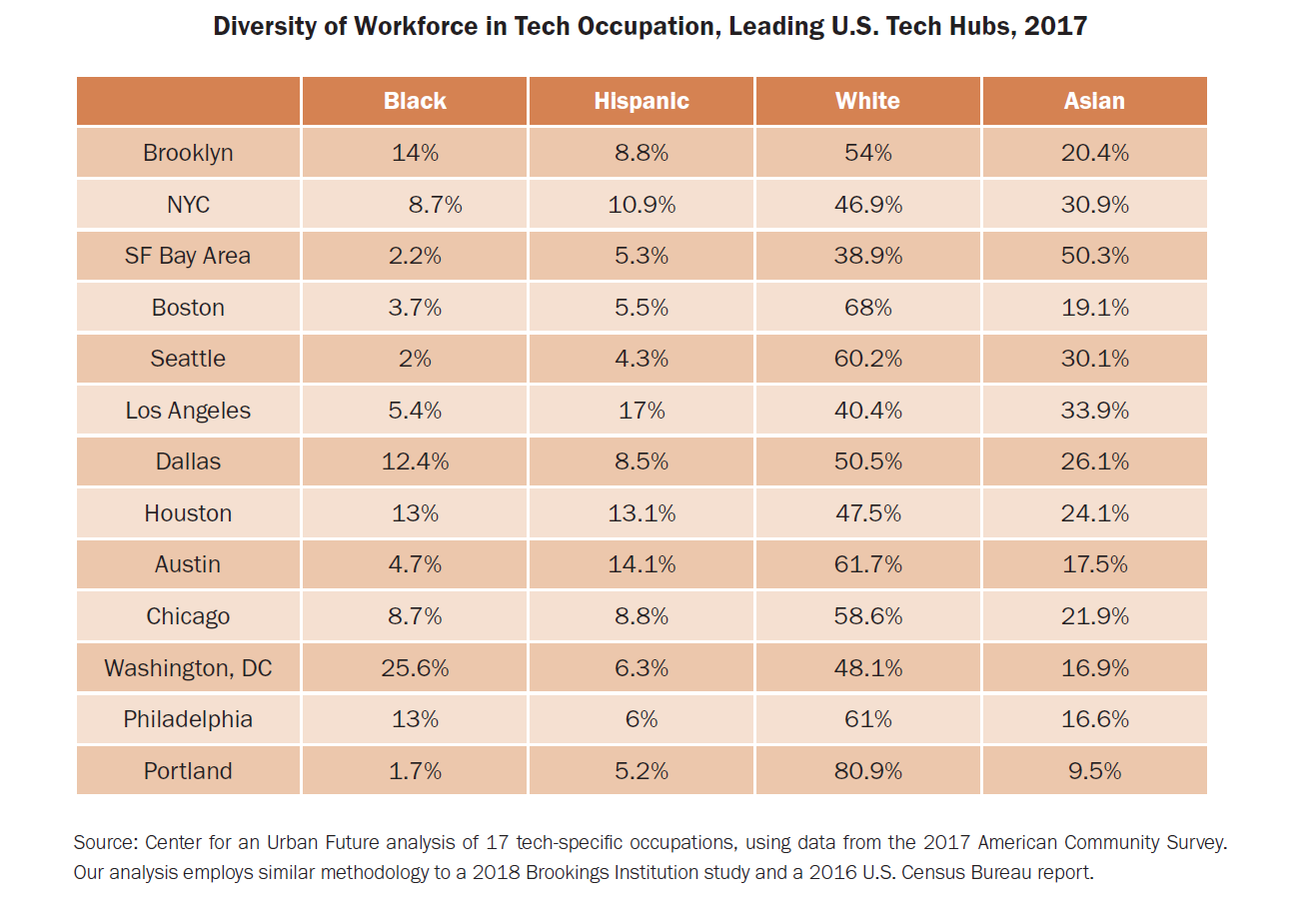

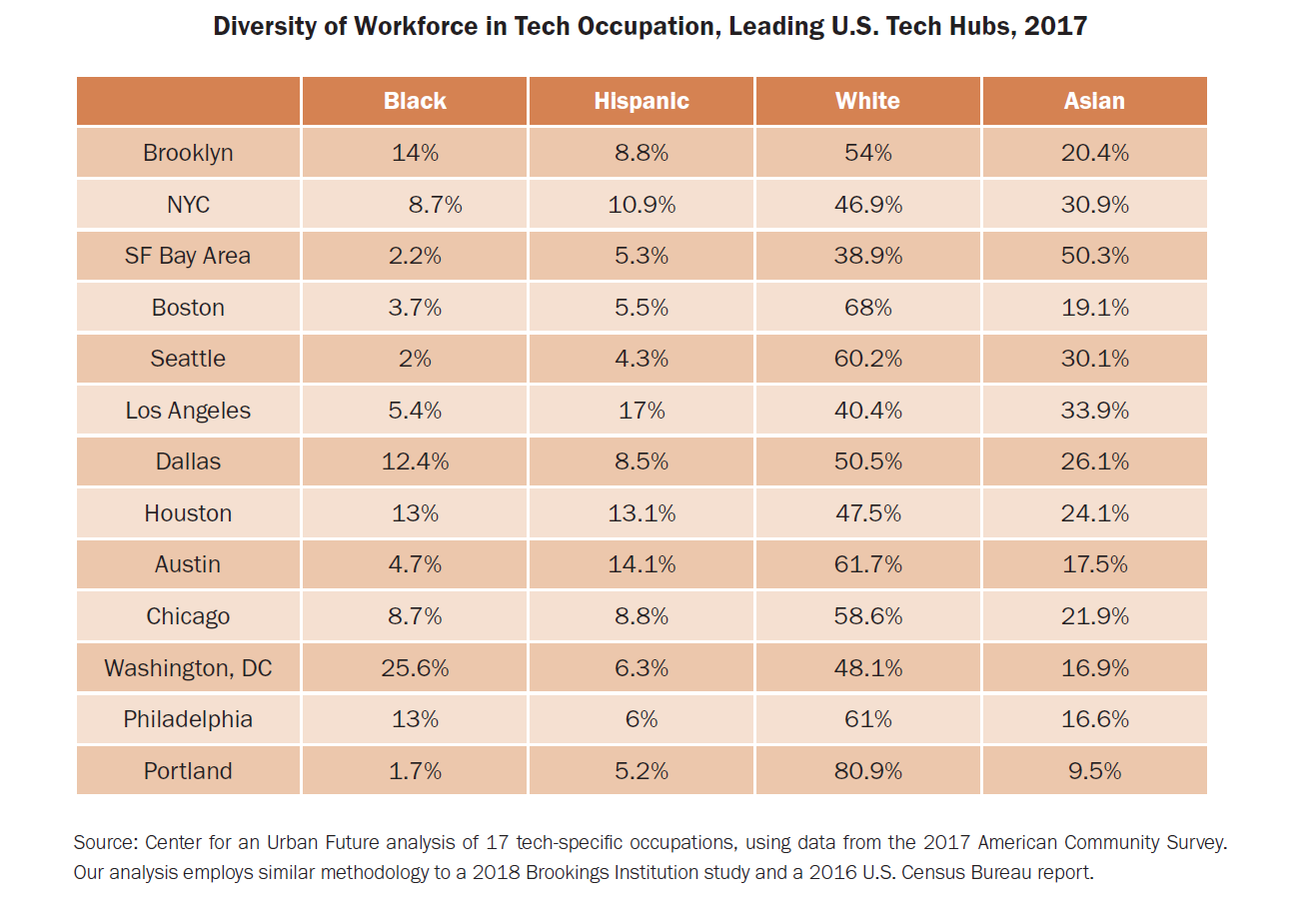

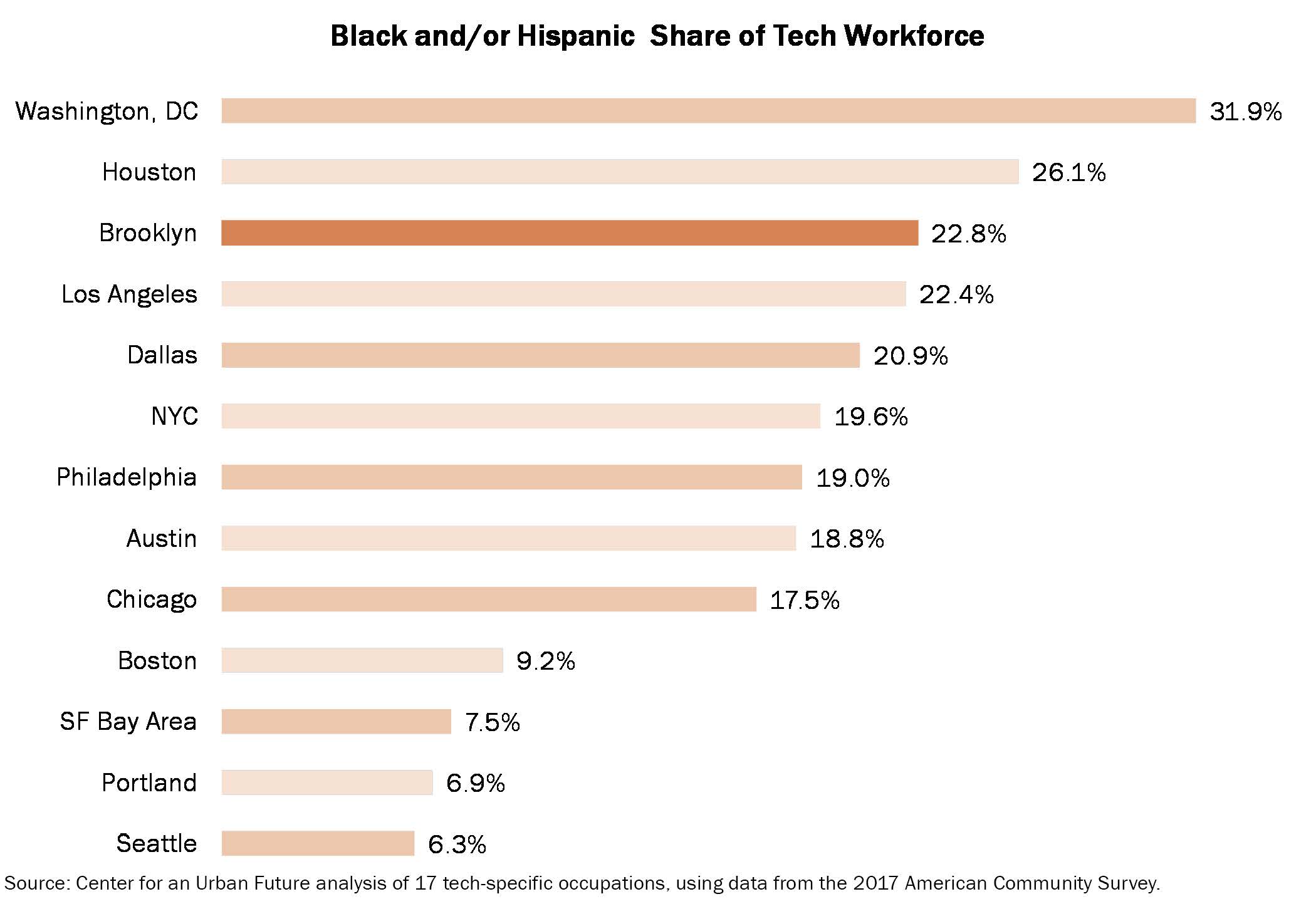

Brooklyn is far from the only city with a troubling opportunity gap in the innovation economy. In fact, an analysis we conducted for this report shows that Brooklyn’s tech workforce is notably more diverse than several other leading tech hubs. According to our analysis of 17 tech-specific occupations, Black and Hispanic workers account for 22.8 percent of Brooklyn’s tech workforce (14 percent Black and 8.8 percent Hispanic).1 This is significantly higher than Boston (9 percent Black and Hispanic combined), the San Francisco Bay Area (7 percent), and Seattle (6 percent).

The comparatively diverse workforce is a clear strength for Brooklyn’s innovation economy. But there is still much more progress to be made in a borough where the overall workforce is 27 percent Black and 21 percent Hispanic.2

Our research took a close look at how to expand access to the jobs in Brooklyn’s innovation economy. We conclude that the borough’s leading stakeholders—including policymakers, leaders of academic institutions, heads of workforce development organizations, philanthropic foundations, and innovation economy employers—will need to make meaningful new investments to expand and improve the borough’s education and workforce training infrastructure. In particular, Brooklyn’s stakeholders will need to address the following specific challenges that were surfaced in our research:

- Greatly expand the number of Brooklyn residents with a college credential – A large share of the well-paying jobs in the innovation economy typically require at least a bachelor’s degree, but just 35 percent of adults in Brooklyn hold a BA or higher, compared to 61 percent in Manhattan—and many of Brooklyn’s college graduates are more recent arrivals from other cities. College attainment rates are considerably lower in many neighborhoods, including Brownsville (where 13.6 percent of adults have a BA or higher), East New York (14 percent), Canarsie (18.6 percent), Sunset Park (19 percent) and East Flatbush (22.5 percent).

- Scale up the borough’s tech training programs – Although there are some notable exceptions, Brooklyn is home to relatively few training organizations with specific, in-depth programs tailored to careers in technology, creative industries, and innovative manufacturing, and most programs are serving just a few dozen participants annually. Moreover, the vast majority of the borough’s tech training programs only offer basic digital literacy and computer skills. Though there are a handful of more in-depth tech training programs that can lead directly to a well-paying tech job, these programs are also small, collectively serving no more than a few hundred people each year.

- Increase the number of employers that recruit and hire local residents – Too few of the borough’s employers in the innovation industries have established efforts to hire locally, recruit from CUNY, partner with the borough’s workforce development organizations, and offer hands-on career-exploration opportunities and paid internships to Brooklyn residents. There are a number of important exceptions, including dozens of companies that work with the place-based employment centers at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, Industry City, and Brooklyn Army Terminal. But there’s no question that a lot more Brooklyn-based innovation companies will need to take affirmative steps to recruit, hire, and train local residents.

- Expand work-based learning – There are hardly any apprenticeship programs so far in Brooklyn’s tech or creative sectors, although a new apprenticeship program for CNC technicians is connecting Brooklynites to jobs in advanced manufacturing. And while Brooklyn has a number of new Career and Technical Education (CTE) programs in public high schools, just one is in computer science and too few programs have meaningful partnerships with Brooklyn employers or are embedded among the borough’s job clusters.

- Strengthen Brooklyn’s CUNY campuses and foster partnerships between these colleges and local employers – Brooklyn’s four CUNY colleges have an important role to play in expanding access to careers in the innovation economy. As one example, graduates of Downtown Brooklyn–based New York City College of Technology (City Tech)—where 61 percent of students come from households earning under $30,000 annually—have the highest median earnings one year after graduation of all CUNY colleges citywide ($41,564), serving as a testament to the power of a postsecondary credential aligned with STEM careers. But all four Brooklyn-based CUNY institutions could benefit from additional resources and from investments to more closely align with the needs of employers in the innovation economy. For example:

- None of the Brooklyn-based CUNY campuses offers a bachelor’s degree program in engineering.3

- In 2016-17, the four Brooklyn CUNY campuses produced just 2,275 STEM graduates, with roughly half (1,203) coming from City Tech. Although the number has increased in recent years, there’s an opportunity to further boost these numbers.

- Only 15.4 percent of undergraduates at Medgar Evers College and 19.4 percent of students at City Tech participated in an internship, according to the 2018 CUNY Student Experience Survey. Of the borough’s three senior colleges, only Brooklyn College (where 23 percent of undergrads participated in an internship) surpassed the citywide senior college average (21.7 percent). Meanwhile, just 10.2 percent of students at Kingsborough Community College participated in an internship, which is roughly on par with the citywide community college average (10.3 percent).

- Expand bridge programs – Brooklyn has veryfew bridge programs designed to connect people with the greatest barriers to employment—like limited English and math skills and no high school diploma—to job training and further education.

Brooklyn has a golden opportunity to make progress on both areas that are the focus of this report: keeping its innovation economy growing and expanding access to the well-paying jobs in this sector. But it will requirepublic sector leaders—in Brooklyn and at City Hall— working closely with leaders from industry, academic institutions, and nonprofit workforce organizations to make new investments and institute new policies to help the borough overcome some key challenges.

This report outlines the key obstacles to growing Brooklyn’s innovation economy and creating new pathways into these jobs—and it puts forth a series of achievable recommendations to overcome these challenges and realize the borough’s immense potential to develop a larger and more inclusive innovation economy.

1. To examine the racial and ethnic composition of Brooklyn’s tech sector, we analyzed 17 tech-specific occupations, such as database administrators, web developers, and computer network architects, using data from the 2017 American Community Survey and employing similar methodology to a 2018 Brookings Institution study and a 2016 U.S. Census Bureau report.

2. Center for an Urban Future analysis of data from the 2013-2017 American Community Survey.

3. CUNY Office of Institutional Research and Assessment. Of the 594 engineering grads at CUNY senior colleges in 2016-2017, zero were at Brooklyn schools. All of the 594 were at City College, Baruch & CSI (and one at CUNY J School).