Higher education should be a ladder to career opportunity and upward mobility. But for many students at underperforming for-profit colleges, it has become a greased slide to student loan default and low-wage work instead. New York State is home to dozens of these schools in nearly every corner of the state. While some lead to career-track jobs and middle-class wages, data shows that thousands of students enrolled in for-profit programs statewide graduate with a degree but still end up stuck in low-wage jobs that provide little ability to pay off student debt.

New York State’s 141 for-profit colleges offer a variety of career-oriented programs in New York State, ranging from courses in medical billing to programs in building trades. At nearly one in ten of these programs (9 percent), graduates earned less than the 2015 federal poverty threshold of $12,331, a shockingly poor outcome.1 However, the vast majority of for-profit college graduates fared little better. At 73 percent of all programs, graduates earned less than $25,000, the average wage of high school graduates between ages 25 and 32.2

Graduates of for-profit programs also found themselves with particularly high levels of student debt—especially given their modest incomes. In nearly four in ten (38 percent) for-profit programs, graduates’ student loan repayments totaled more than 8 percent of their annual earnings, placing an enormous burden on these students as they entered the workforce.3 By comparison, graduates contributed 8 percent or more of their earnings to make loan payments at just 1 percent of nonprofit programs and 4 percent of public occupational programs.

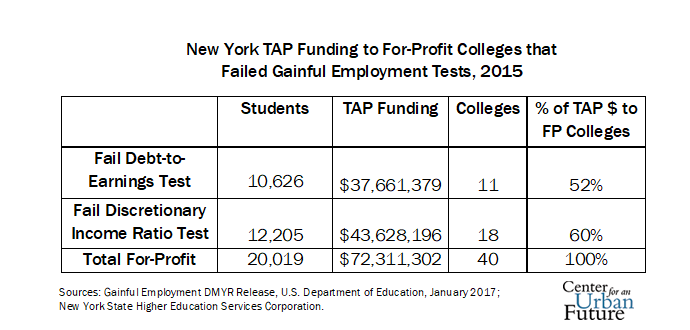

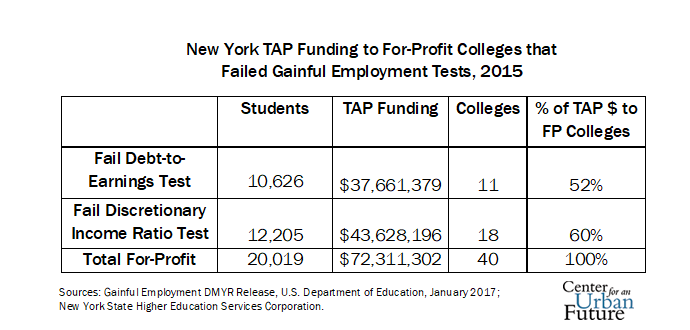

Yet even the worst performing for-profit schools receive tens of millions annually in state subsidies from New York’s Tuition Assistance Program (TAP). In 2015, more than $37 million in state TAP dollars went to colleges with at least one program that failed or nearly failed the U.S. Department of Education’s standard for post-college outcomes. What’s more, $31 million went to colleges at which no more than 30 percent of former students made a single payment to their loan principal within three years of entering repayment.

In 2014, the U.S. Department of Education took pioneering steps to end this type of misuse of government financial aid. By establishing a grading system called the “gainful employment” standard, the department planned to screen out of the federal financial aid pool colleges that consistently turned out graduates who—even with a degree—couldn’t access decent-paying jobs and were highly likely to default on their student loans. The new administration in Washington has chosen not to enforce the gainful employment rule, but Governor Cuomo and the state legislature have the power to enact—and enforce—a similar standard in New York State. Other states like California have taken this step, and New York should join them in 2018.

Creating a gainful employment standard in New York would limit TAP funds to colleges whose graduates earn enough to manage their student loan debt, ensuring that state tuition dollars are spent as effectively as possible. Most importantly, in the long term, it would steer more New Yorkers to colleges—public and private—that work.

This policy brief—funded by the Working Poor Families Project and informed by numerous interviews with higher education experts, policymakers, and education officials—offers the first ever analysis of postgraduate earnings and student loan burdens across New York State and presents a plan by which state policymakers can take action to ensure that the state’s crucial investments in higher education result in real economic gains for its students.

For-profit colleges occupy a modest corner of New York’s higher education sector, but one with an outsized impact on low-income and minority communities and nontraditional students. For many New Yorkers, these programs are recognizable as the occupational training schools that commonly advertise on subways. For students enrolled in these programs, including a disproportionate share of working adults who juggle family and job obligations while attending school, for-profit colleges entice with the promise of a quick route to better wages.

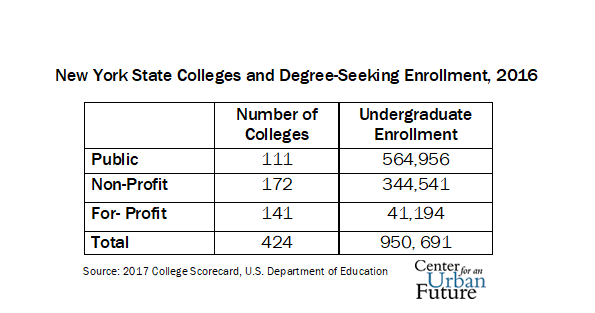

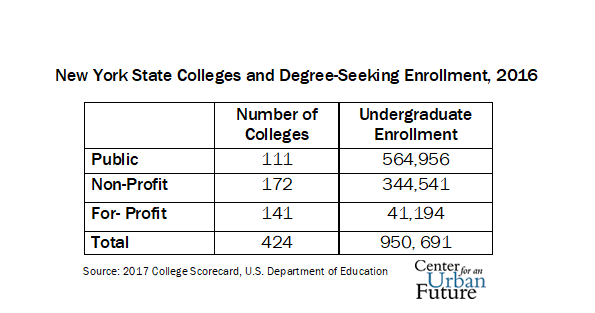

According to data from the U.S. Department of Education’s College Scorecard, about 4 percent of degree-seeking college students in New York—some 41,000 students—are enrolled in for-profit colleges.4 Degree-seeking students in New York’s for-profit college sector are more likely to be women than are students at public and independent nonprofit colleges. The majority of students at for-profit colleges are also black or Hispanic, and the share of black students is particularly high: 30 percent of degree-seeking students at for-profit colleges are black, twice as many as at public colleges and triple the rate of nonprofit institutions. Roughly half describe themselves as first-generation college students, meaning they will aspire to be the first in their immediate family to obtain a college degree.5 In general, students who enroll in for-profit colleges have fewer economic resources and less “college knowledge” than students at many nonprofit and public colleges. They are also likely to be older, returning to the educational system from the workforce rather than transitioning directly from high school.

Although there are a number of reputable for-profit schools in New York—and nationally—a disproportionately large share of these colleges have poor track records. For example, graduates of the College of Westchester’s associate’s degree program in web design face average annual loan payments of $2,563 and median annual earnings of $13,901. At Cheryl Fell’s School of Business in Niagara Falls, students who earn a medical secretary certificate end up with average annual loan payments of $1,899 and median annual earnings of just $9,731.6

Over the past few years, investigations revealing abusive practices hurt the for-profit sector’s reputation among investors and prospective students and led the federal government to take action. In 2014, the U.S. Education Department issued a new rule enforcing language in the federal Higher Education Act, which sets the rules for Pell Grants and Stafford Loans, stating that colleges may only use federal aid for occupational programs that lead to “gainful employment in a recognized occupation.” In short, the gainful employment standard holds that if a college program receives federal funding to prepare students for careers as auto mechanics or dental hygienists, for example, then most of those students should be able to get jobs that allow them to pay back their loans. Gainful employment covers public, nonprofit, and for-profit career education programs that served over 16 million students between 2008 and 2014.7

The federal government spends nearly $130 billion annually on grants and loan subsidies for students to attend occupational programs, some of which provide demonstrably poor value. Federal law had long required for-profit colleges to demonstrate that their programs actually lead to jobs, since these colleges lack the accountability built into nonprofit and public institutions. The Department of Education put teeth into that requirement by specifying minimum average post-graduation outcomes needed to qualify for financial aid. More recently, however, the agency has frozen enforcement of gainful employment and signaled an intention to dismantle its key components.

Under gainful employment, colleges with occupational programs of study must send the U.S. Department of Education information on students who are enrolled in those programs. The department then works with the Social Security Administration to get incomes for those programs’ graduates and creates a debt-to-earnings ratio. In doing so, the Department of Education examines two measures:

- Debt to earnings: A program passes the gainful employment test if the typical annual loan payments for graduates fall below 8 percent of their total annual earnings. If loan payments rise above 12 percent, the program fails. If loan payments are between 8 percent and 12 percent of total earnings, the program is in the “zone,” a warning area intended to prompt the school to improve performance.

- Discretionary income threshold: A program passes if annual loan payments fall below 20 percent of discretionary earnings, defined as annual earnings that are available to pay bills after paying for basic needs (150 percent of the federal poverty standard, or $17,050).8 The program fails if loan payments rise above 30 percent of discretionary income, and 21 to 30 percent is in the warning zone.

A program that fails both standards loses eligibility for Title IV federal financial aid. A program that falls into the zone in both standards for four years also loses eligibility.

This report analyzes the first year of gainful employment data, issued in January 2017, along with several other objective metrics for assessing student loan outcomes in New York State. The outcomes are serious cause for concern.

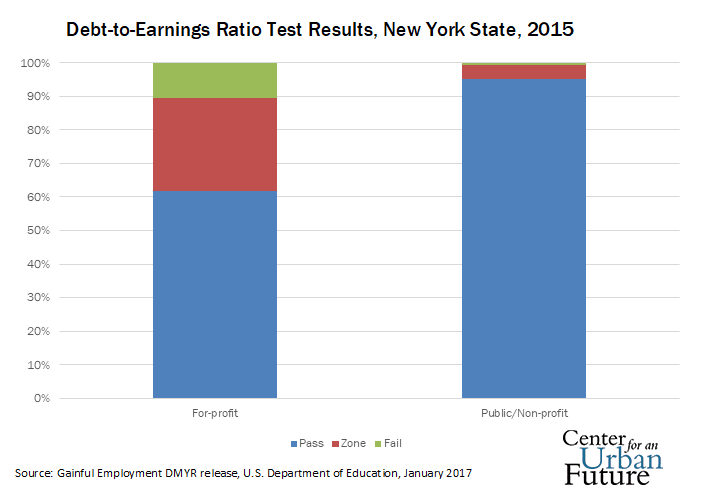

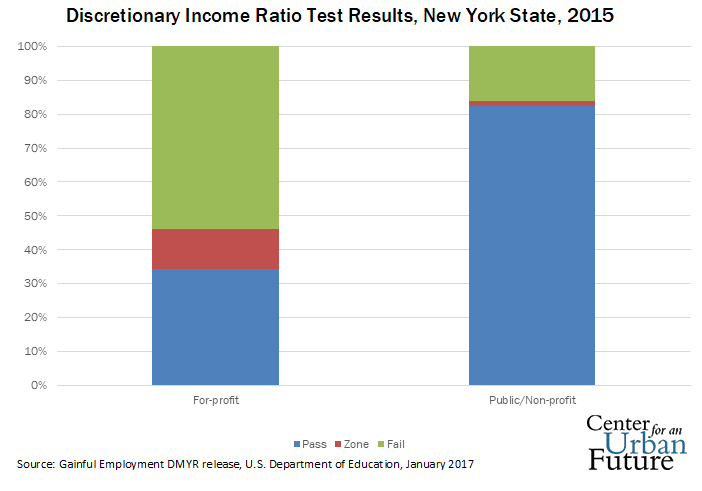

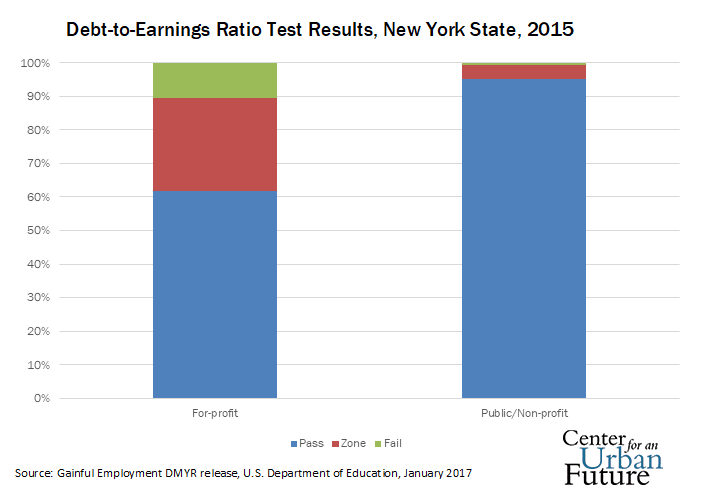

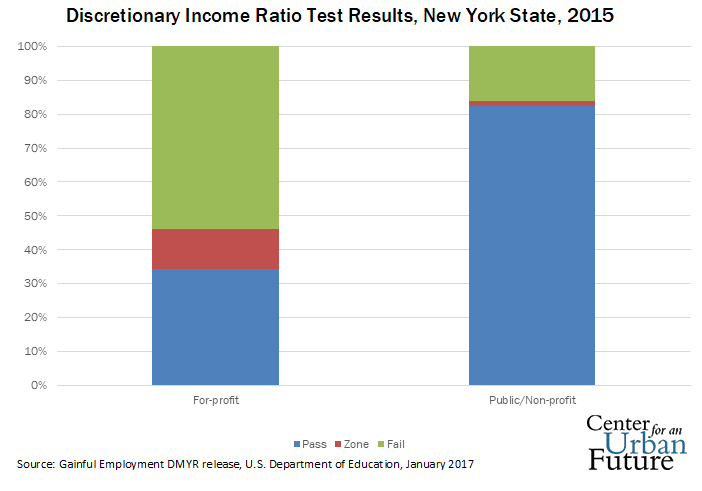

In New York, 10 percent of for-profit programs fail the debt-to-earnings test, and another 28 percent fall into the zone, compared to just 1 percent and 4 percent of nonprofit and public programs, respectively.9 The issues faced by graduates come into sharper relief, however, when examining the discretionary income threshold. Only one-third of for-profit programs in New York pass, compared to 82 percent of nonprofit and public programs.

This means that the majority of for-profit graduates are likely to struggle to make their student loan payments after covering rent, food, and transportation—especially in New York City, with its high cost of living. A program of study loses financial aid eligibility only if it fails both gainful employment tests. However, colleges must inform students of their performance, and students may think twice about attending a college offering high debt burden and low postgraduate income.

As federal policymakers signal their intent to roll back oversight of the for-profit college sector, New York should protect its residents by filling this impending gap with a New York–specific gainful employment standard. The state could do this by setting minimum standards for higher education institutions to qualify for TAP. In addition, the state should impose a similar standard on for-profit colleges that seek eligibility for the Enhanced Tuition Award program, which currently provides tuition subsidies to nonprofit colleges.10

As federal policymakers signal their intent to roll back oversight of the for-profit college sector, New York should protect its residents by filling this impending gap with a New York–specific gainful employment standard. The state could do this by setting minimum standards for higher education institutions to qualify for TAP. In addition, the state should impose a similar standard on for-profit colleges that seek eligibility for the Enhanced Tuition Award program, which currently provides tuition subsidies to nonprofit colleges.10

Other states have already adopted these policies, with positive results for students and taxpayers. California enacted a gainful employment standard for state financial aid in 2012, which has resulted in savings of more than $100 million annually. These funds are redirected to the state’s public higher education system, where students enroll in colleges with much lower student loan default rates.11 This is the future that New York’s aspiring students deserve, too.

Vulnerable New York college students are betting on a high-risk degree

At a time when a college degree has become a necessity for most well-paying jobs, getting low-income college students to graduation remains a critical problem for New York. More than seven million New Yorkers over age 25 lack a college degree and graduation rates remain stubbornly low at public community colleges and universities from the Finger Lakes to the Bronx.12

Today, according to data from the Working Poor Families Project, six out of ten working poor families in New York have no adults with postsecondary education at all.13 For most of these families, a college degree can mean the difference between upward mobility with family-sustaining wages and a lifetime of poverty. Yet the costs of attending college often outstrip the ability of working students to pay, especially at non-public colleges. And taking out student loans is a nerve-wracking gamble on both timely graduation and a boost in postgraduate income.

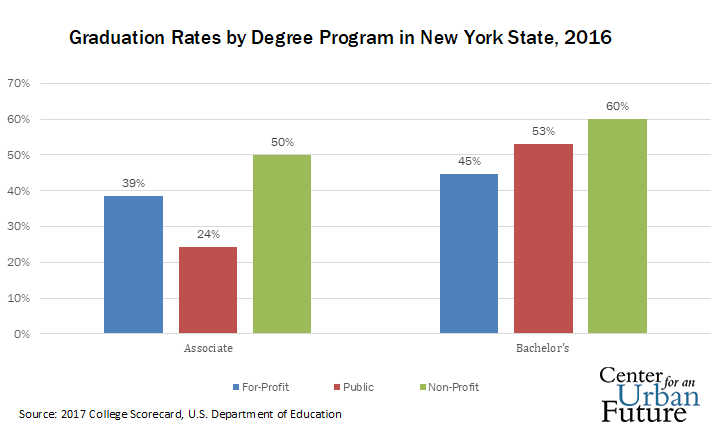

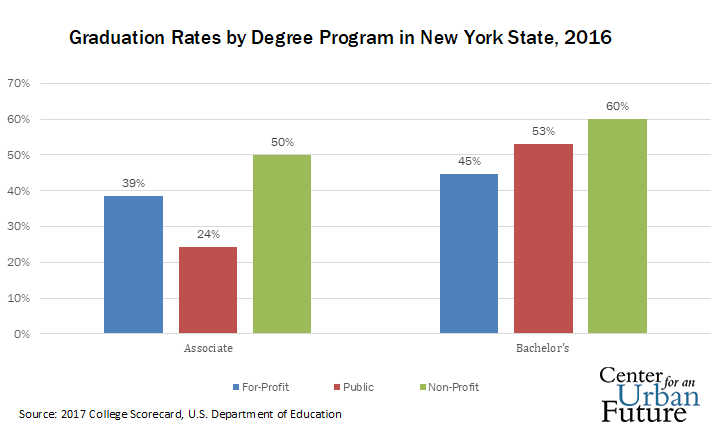

This problem is compounded by the high costs and poor outcomes at too many of the state’s for-profit colleges. To be sure, both for-profit and public colleges have distressingly low graduation rates. The six-year graduation rate for all first-year full-time students seeking a bachelor’s degree at for-profit colleges in 2016 was just 43 percent, significantly lower than the graduation rate at four-year public (53 percent) and non-profit colleges (68 percent).14The three-year graduation rate for students seeking an associate’s degree at two-year for-profit colleges was 39 percent, and at two-year public colleges, 24 percent.15

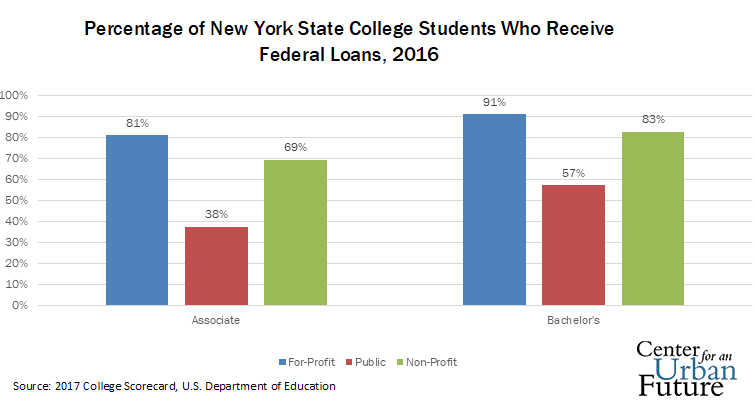

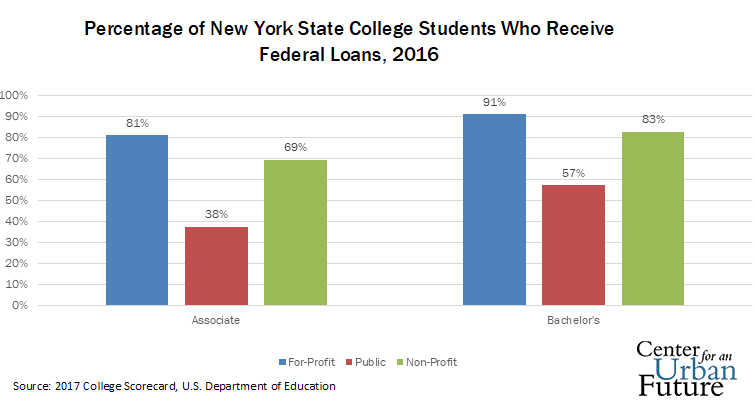

But even where the graduation rate at a for-profit college is comparable to other colleges, the consequences of dropout are more severe, due to higher tuition costs and the near-universal need to borrow money. Students who take out a student loan and then drop out are far more likely to default on their loans. Only 24 percent of students at the state’s public two-year colleges obtain loans, compared to 81 percent of students seeking associate’s degrees at the state’s for-profit institutions.16 Likewise, nine in 10 students seeking bachelor’s degrees at for-profit colleges take out loans, compared to 57 percent of students at public four-year colleges.

But even where the graduation rate at a for-profit college is comparable to other colleges, the consequences of dropout are more severe, due to higher tuition costs and the near-universal need to borrow money. Students who take out a student loan and then drop out are far more likely to default on their loans. Only 24 percent of students at the state’s public two-year colleges obtain loans, compared to 81 percent of students seeking associate’s degrees at the state’s for-profit institutions.16 Likewise, nine in 10 students seeking bachelor’s degrees at for-profit colleges take out loans, compared to 57 percent of students at public four-year colleges.

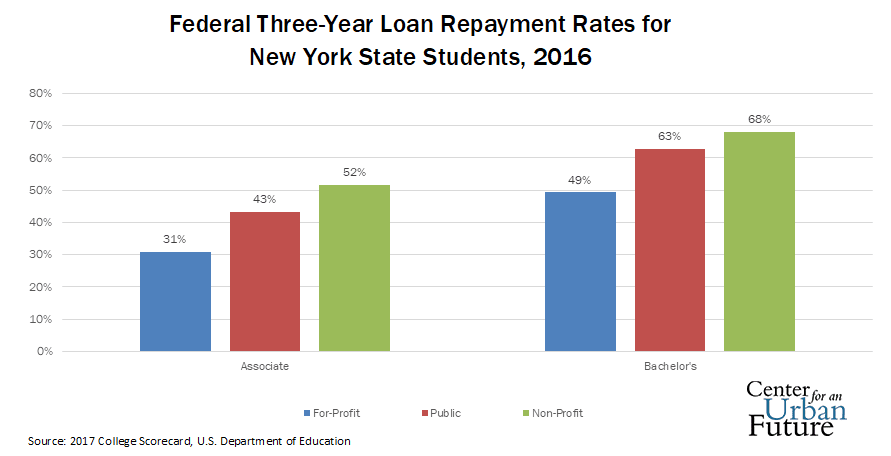

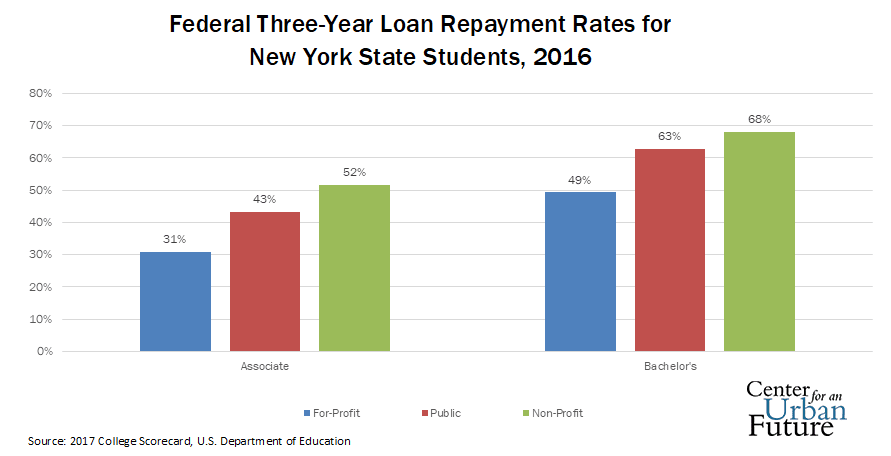

While gainful employment measures debt burden on graduates, another metric measures the ability of all students to repay their loans. The repayment rate shows whether students who leave the college, either as graduates or dropouts, make even a single payment to loan principal within three years of leaving college. In New York, only 30 percent of student loan borrowers seeking an associate’s degree at a for-profit college make a payment within three years; just under half of student loan borrowers seeking bachelor’s degrees make a payment in that same three-year window.17 These rates are significantly below those of nonprofit and public college graduates.

Students at for-profit colleges almost all borrow, and they are less likely to be able to repay their loans. Combining these two data points reveals that more than half of for-profit students seeking an associate’s degree (56 percent) take out a loan but do not begin to repay it within three years, and the same is true for almost half (46 percent) of for-profit college students seeking a bachelor’s degree. In contrast, only one in five students (21 percent) at public colleges take out a loan and fail to repay it within three years.

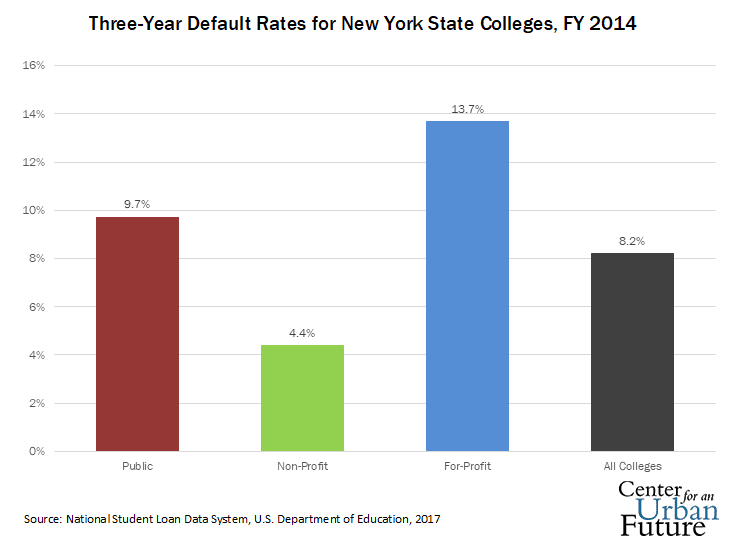

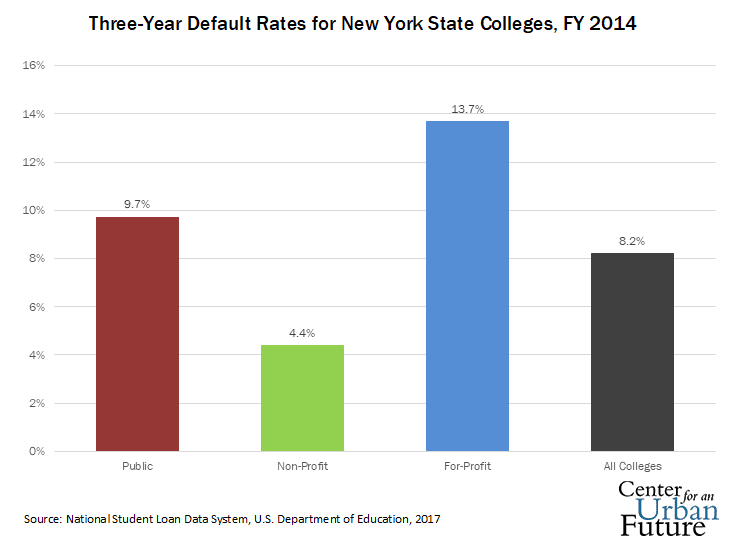

The U.S. Department of Education closely tracks the three-year default rate of federal student loans at colleges eligible for student aid. According to the most recent data on New York, 14 percent of for-profit college graduates default within three years, compared to 10 percent among public college graduates and 4 percent among non-profit college graduates. Sixteen for-profit colleges have cohort default rates above 20 percent, as do five public colleges. Students at for-profit colleges in New York comprise 15 percent of all borrowers, but 25 percent of borrowers in default. Students who are in default on their loans are barred from any further federal or state financial aid, sharply limiting their opportunity to attend a more affordable public college or university.

The three-year default rate understates the actual default risk students face. Nationally, students who entered a for-profit college in 2003–2004 had a 12-year default rate of 47 percent—and a projected 20-year default rate of almost 70 percent.18

Consumer concerns with for-profit colleges

For-profit colleges offer an appealing pitch to prospective students: obtain a marketable credential in an in-demand field, while covering the cost of tuition with a combination of federal and state grant aid and student loans. In theory, students will repay their loans from the added income they gain after graduation.

For some students at certain for-profit colleges, this value proposition works as advertised. Indeed, any higher education institution can meet or fail to meet students’ needs, regardless of ownership control or tax status. Still, this study identified several major risks for students at for-profit colleges, with significant consequences for New York State.

Colleges may not provide accurate or complete information to students. Much of what for-profit colleges tell students may stretch the truth, according to attorneys and consumer advocates who deal on a regular basis with for-profit colleges. For example, Career Education Corporation (CEC), a major for-profit provider, attracted students by claiming that graduates of its various colleges obtained placement in their professional fields ranging from 54 percent to 80 percent. But an investigation by the New York State Attorney General’s Consumer Frauds Bureau found that “CEC inflated its job placement rates . . . and used the inflated placement data to lure prospective students to attend their schools.”19 The settlement noted a practice in which CEC arranged for health companies to hire graduates to work at a one-day health fair and then counted them as employed for purposes of job placement statistics. CEC students were also recruited to programs that lacked program accreditation, such as one for ultrasound technicians, only to discover after graduation that they could not even take the certification exam.20

Aggressive recruitment can attract students who would be better off saying no. Providers and consumer advocates who deal with for-profit colleges report unusually aggressive recruiting tactics. Persis Yu, director of the Student Loan Borrower Assistance Project at the National Consumer Law Center, says that “New York City is one of the worst cities I’ve seen in terms of aggressive recruiting.” Her concern is shared by on-the-ground practitioners. “Our students get barraged with recruiting calls,” says Danae Mcleod, executive director of Grace Outreach, a nonprofit group that supports low-income women in the Bronx. Clients of her organization often receive college marketing calls just before taking their high school equivalency exams, even though such information is supposed to be confidential. The result can be that low-income adults enroll in for-profit colleges who would be better served by a different educational option.

For-profit colleges may be financially unstable. A number of for-profit colleges have gone under over the past several years, raising concerns about financial instability in the sector that could affect students. The best-case resolution involves “teaching out” students in an orderly fashion, either directly or by contract with another institution. But the worst-case scenario has happened as well. When Everest Institute, a subsidiary of Corinthian Colleges in Rochester, shut down in 2015, former students were abruptly saddled with student loan debt, no degrees, and no route to continue their studies.21

New York’s taxpayer stake in for-profit colleges

The rocky financial condition of former for-profit college students is more than just a private ordeal. New York is affected more broadly by the millions of dollars the state spends on financial aid to help students attend for-profit colleges, some of which appear to harm students’ career aspirations rather than helping them. The state’s support for for-profit colleges could rise again, since the state legislature enacted a law to extend the Excelsior Scholarship’s Enhanced Tuition Award benefit to students at for-profit colleges.

In 2015, $72 million in TAP funding went to cover tuition for 20,019 students at for-profit colleges, 8 percent of the state’s $956 million TAP budget. Of that amount, just over half went to for-profit colleges in which at least one program of study failed the debt-to-earnings test; six dollars in ten went to for-profit colleges in which at least one program of study failed the debt-to-discretionary-earnings test. Thus, more than $37 million in TAP dollars was spent on colleges in which some of the students accumulated loan burdens that the U.S. Department of Education considered financially destabilizing. In addition, $31 million in TAP dollars went to colleges in which no more than 30 percent of students made a single loan payment to principal after three years.

Take the case of Bryant & Stratton College, which has six campuses across New York State and 2,277 students who received $9 million in TAP benefits in 2015—about one in six TAP dollars claimed by for-profit colleges. According to the U.S. Department of Education’s gainful employment database, four of Bryant & Stratton’s 16 programs of study failed the debt-to-earnings test, including a bachelor’s degree program in criminal justice. Graduates in this program make annual loan payments of $4,272 annually on a median salary of $29,036, meaning that they must devote 15 percent of their annual income to repaying student loans. Not surprisingly, Bryant & Stratton students struggle with their loan balances. Only 18 percent of Bryant & Stratton students are able to make even a single payment to their student loan principal within three years of entering repayment, according to the federal College Scorecard.

New York’s financial exposure to for-profit colleges is about to get even larger. A provision of the state budget signed into law in April 2018 opens the Enhanced Tuition Award program— which previously only went to private nonprofit colleges—to the for-profit sector. Lacking any screening standards, the expanded program may attract students to institutions that fail to serve their best interests..

Learning from the California model

New York should learn from California’s experience and direct critical state tuition dollars to programs that work. In California, higher education spending has been tied to quality assurance for the last six years. In 2012, the nation’s largest state struggled with a budget crisis that threatened funding for the state Cal Grant program. The state responded by restricting Cal Grant eligibility in a way that actually benefited students. To qualify for Cal Grant eligibility, a higher education institution must have a minimum graduation rate of 30 percent and a loan default rate of less than 15.5 percent. Colleges at which fewer than 40 percent of students take out loans are exempt. The following year, more than 150 for-profit colleges lost Cal Grant eligibility.22 Since 2012, the gainful employment program has saved the state nearly $100 million, which the state has reinvested in colleges that provide far better student outcomes.23

The leadership of the California for-profit sector argued that the ultimate losers in such a policy would be students deprived of access to college opportunities. That is a concern to take seriously. In California, as in New York, students at for-profit colleges are predominantly low-income minority women in their 20s and 30s whose routes to upward mobility are few.

Yet two studies conducted by Stephanie Cellini, a professor at George Washington University, show that New York has little to fear from cutting off underperforming colleges. In a 2014 study, Cellini and a coauthor compared net prices of for-profit colleges eligible for Pell Grants under Title IV with other for-profit colleges that are not eligible.24 She found that the Pell-eligible colleges actually raise tuition to reflect the value of the financial aid for which they qualify. As a result, eliminating TAP eligibility for some for-profit colleges may simply lead them to reduce tuition, in order to remain competitive with other programs.

In a 2017 study, Cellini tackled the harder question: What happens to college access when for-profit colleges shut down? Cellini and her coauthors tracked enrollment patterns among Pell-eligible students after for-profit colleges were sanctioned by the federal government and closed.25 Enrollment at local community colleges rose by a level that more than compensated for the drop in for-profit enrollment. Furthermore, each for-profit college that received sanctions resulted in 31 fewer student loan defaults over the next two years. That’s because community colleges charge about one-quarter the tuition of for-profit colleges, relieving much of the burden on students to take out loans.

1. “Programs” refers to individual courses of study—e.g., dental hygiene, child care, or web design—that result in a credential. Most colleges offer multiple programs with varying results, which is why the outcomes discussed in this report are for individual programs, not colleges as a whole.

2. U.S. Census Bureau, 2015 Federal Poverty Threshold. Jaison Abel and Richard Deitz, “College may not pay off for everyone,” New York Federal Reserve, September 2014. Accessed from http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2014/09/college-may-not-pay-off-for-everyone.html#.VAmvfGSwI0g

3. A career education program loses eligibility for federal financial aid if it fails both gainful employment tests: graduates with a debt-to-earnings ratio of 12 percent or higher and a debt-to-discretionary-income ratio of 30 percent or higher. Ratios of 8 percent and 20 percent, respectively, put a college in the “zone,” a probationary class that also leads to expulsion after four years. See 34 C.F.R. §§ 668.404-668.406.

4. 2017 College Scorecard. Data accessed from https://collegescorecard.ed.gov/data/.

5. These figures are similar to the national profile of for-profit college students. See Cellini, Stephanie and Darolia, R, 2016. Different degrees of debt: Student borrowing in the for-profit, nonprofit, and public sectors. Brown Center on Education Policy, Brookings Institution (Washington DC). June 2016, p.6.

6. Gainful Employment DMYR 2015 Final Rates, U.S. Department of Education. Released January 2017. Internal data from New York State Higher Education Services Corporation.

7. Michael Itzkowitz, “How the ‘gainful employment’ rule protects students and taxpayers,” Third Way, January 5, 2017. Accessed from http://www.thirdway.org/memo/how-the-gainful-employment-rule-protects-students-and-taxpayers.

8. Discretionary earnings are determined by subtracting 150 percent of the federal poverty standard, or $17,050, from total earnings. If total earnings are $30,000, discretionary earnings would be $30,000-$17,050=$12,950.

9. Gainful Employment DMYR 2015 Final Rates. Note that some colleges have appealed their gainful employment findings.

10. The Excelsior Scholarship program, enacted in June 2017, covers tuition at all public colleges and universities in New York State for students who meet several criteria, including family income lower than $125,000, being on track for on-time graduation, and tuition not covered by other financial aid programs. The Enhanced Tuition Award program provides tuition subsidies to students at independent non-profit colleges using similar eligibility standards.

11. Mac Taylor, An analysis of new Cal Grant eligibility rules, California Legislative Analyst’s Office, January 7, 2013. Also see Cellini, Stephanie, Darolia, Rajeev, and Turner, Lesley. 2017. Where do students go when for-profit colleges lose federal aid? Working Paper No. 17-12, May 2017.

12. Analysis of 2015 American Community Survey by Population Reference Bureau for the Working Poor Families Project.

13. Ibid.

14. Data analysis based on 2017 College Scorecard database. Note that the official graduation rate is based on 150% of the expected time to completion, which is three years for students seeking an associate’s degree and six years for students seeking a bachelor’s degree.

15. The community college graduation rate is undercut by the large number of students who transfer to four-year colleges without obtaining an associate’s degree first. Also note that federal data on college graduation is less accurate than administrative data obtained directly from colleges, but in this case the topline numbers are nearly identical. A previous study found the three-year community college graduation rate to be 25 percent and the six-year rate to be 32 percent. See Tom Hilliard, Struggling to the Finish Line, Center for an Urban Future, December 2017.

16. 2017 College Scorecard, U.S. Department of Education.

17. Ibid.

18. Judith Scott-Clayton, The looming student loan default crisis is worse than we thought, Evidence Speaks Reports, Vol 2, #34. Brookings Institution, January 10, 2018. Accessed from https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-looming-student-loan-default-crisis-is-worse-than-we-thought/.

19. “A.G. Schneiderman announces groundbreaking $10.25 million dollar settlement with for-profit education company that inflated job placement rates to attract students.” Press Release, Office of the New York State Attorney General, undated. Accessed from https://ag.ny.gov/press-release/ag-schneiderman-announces-groundbreaking-1025-million-dollar-settlement-profit.

20.Carolyn Fast, Special Counsel, Consumer Frauds and Protection Bureau, Office of the New York State Attorney General. Personal interview.

21. See https://www.mcny.edu/blog/2017/09/06/abrupt-closure-tci-college-continues-pattern-higher-ed-diversity-loss-nyc/.

22. “1st-in-nation graduation and loan default rate benchmarks eliminate 154 schools.” Press release, California Student Aid Commission. July 31, 2012.

23. Kevin Cook. “The growth of Cal Grants,” The PPIC Blog. Public Policy Institute of California. May 19, 2017. Accessed at http://www.ppic.org/blog/growth-cal-grants/.

24. Cellini, Stephanie and Goldin, Claudia. 2014. “Does federal student aid raise tuition? New evidence on for-profit colleges.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 6(4): 174-206.

25. Cellini, Stephanie, Darolia, Rajeev, and Turner, Lesley. 2017. Where do students go when for-profit colleges lose federal aid? Working Paper No. 17-12, May 2017.

Photo Credit: Clay Banks/ Unsplash

As federal policymakers signal their intent to roll back oversight of the for-profit college sector, New York should protect its residents by filling this impending gap with a New York–specific gainful employment standard. The state could do this by setting minimum standards for higher education institutions to qualify for TAP. In addition, the state should impose a similar standard on for-profit colleges that seek eligibility for the Enhanced Tuition Award program, which currently provides tuition subsidies to nonprofit colleges.10

As federal policymakers signal their intent to roll back oversight of the for-profit college sector, New York should protect its residents by filling this impending gap with a New York–specific gainful employment standard. The state could do this by setting minimum standards for higher education institutions to qualify for TAP. In addition, the state should impose a similar standard on for-profit colleges that seek eligibility for the Enhanced Tuition Award program, which currently provides tuition subsidies to nonprofit colleges.10 But even where the graduation rate at a for-profit college is comparable to other colleges, the consequences of dropout are more severe, due to higher tuition costs and the near-universal need to borrow money. Students who take out a student loan and then drop out are far more likely to default on their loans. Only 24 percent of students at the state’s public two-year colleges obtain loans, compared to 81 percent of students seeking associate’s degrees at the state’s for-profit institutions.16 Likewise, nine in 10 students seeking bachelor’s degrees at for-profit colleges take out loans, compared to 57 percent of students at public four-year colleges.

But even where the graduation rate at a for-profit college is comparable to other colleges, the consequences of dropout are more severe, due to higher tuition costs and the near-universal need to borrow money. Students who take out a student loan and then drop out are far more likely to default on their loans. Only 24 percent of students at the state’s public two-year colleges obtain loans, compared to 81 percent of students seeking associate’s degrees at the state’s for-profit institutions.16 Likewise, nine in 10 students seeking bachelor’s degrees at for-profit colleges take out loans, compared to 57 percent of students at public four-year colleges.