Retail is not only one of New York City’s largest industry sectors, it is home to an outsized share of the city’s most accessible jobs. More than 70 percent of the city’s retail workers are Black, Hispanic, and/or Asian, and over 20 percent of the retail workforce is under the age of 25. Fully 81 percent of city residents working in retail live in the four boroughs outside of Manhattan—even though just 58 percent of the city’s retail jobs are physically located in those four boroughs.

But this new analysis finds that the retail sector is lagging well behind the city’s overall jobs recovery and raises concerns about whether this vital and diverse part of the city’s economy will ever get back to its pre-pandemic employment level.

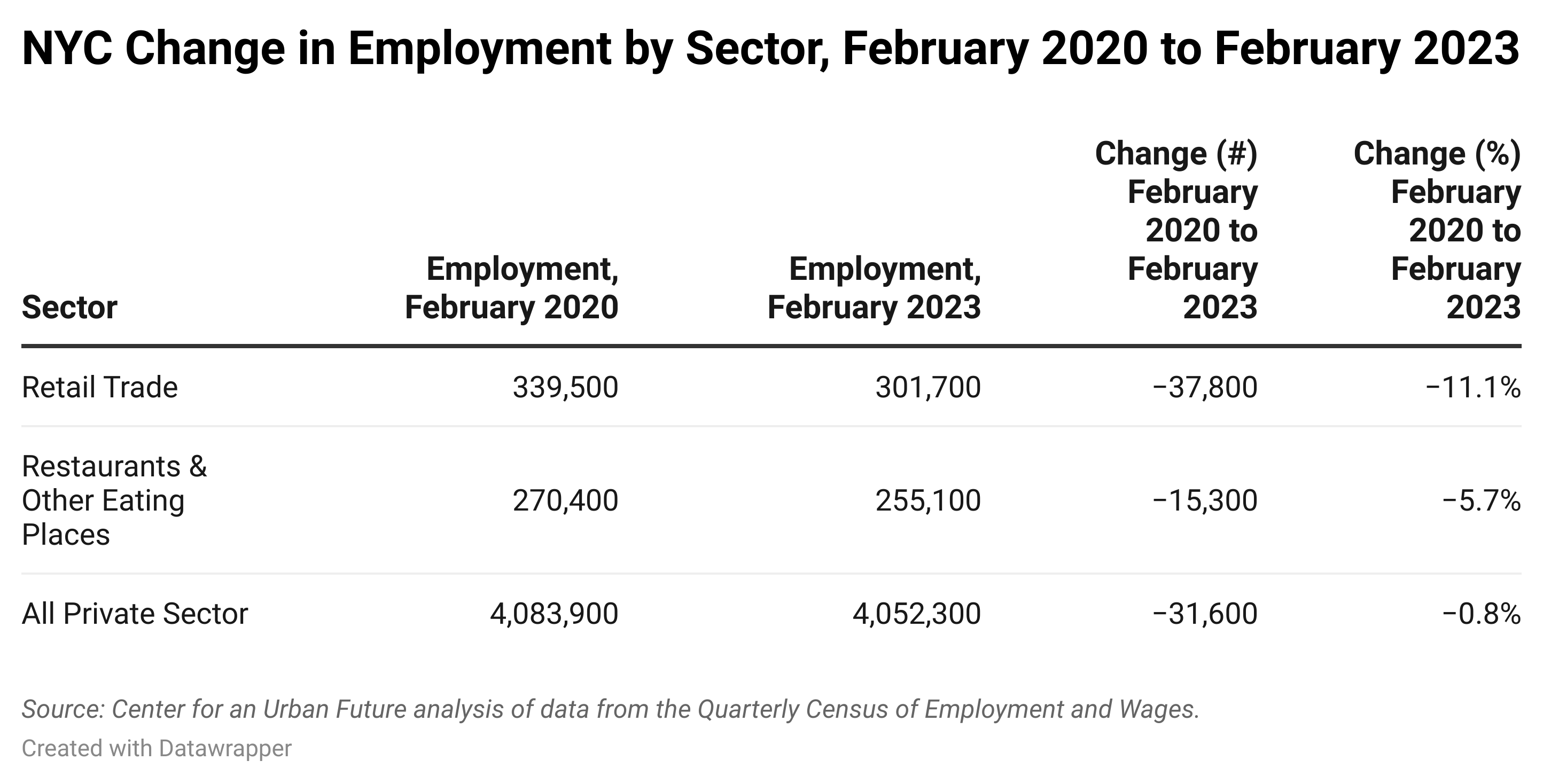

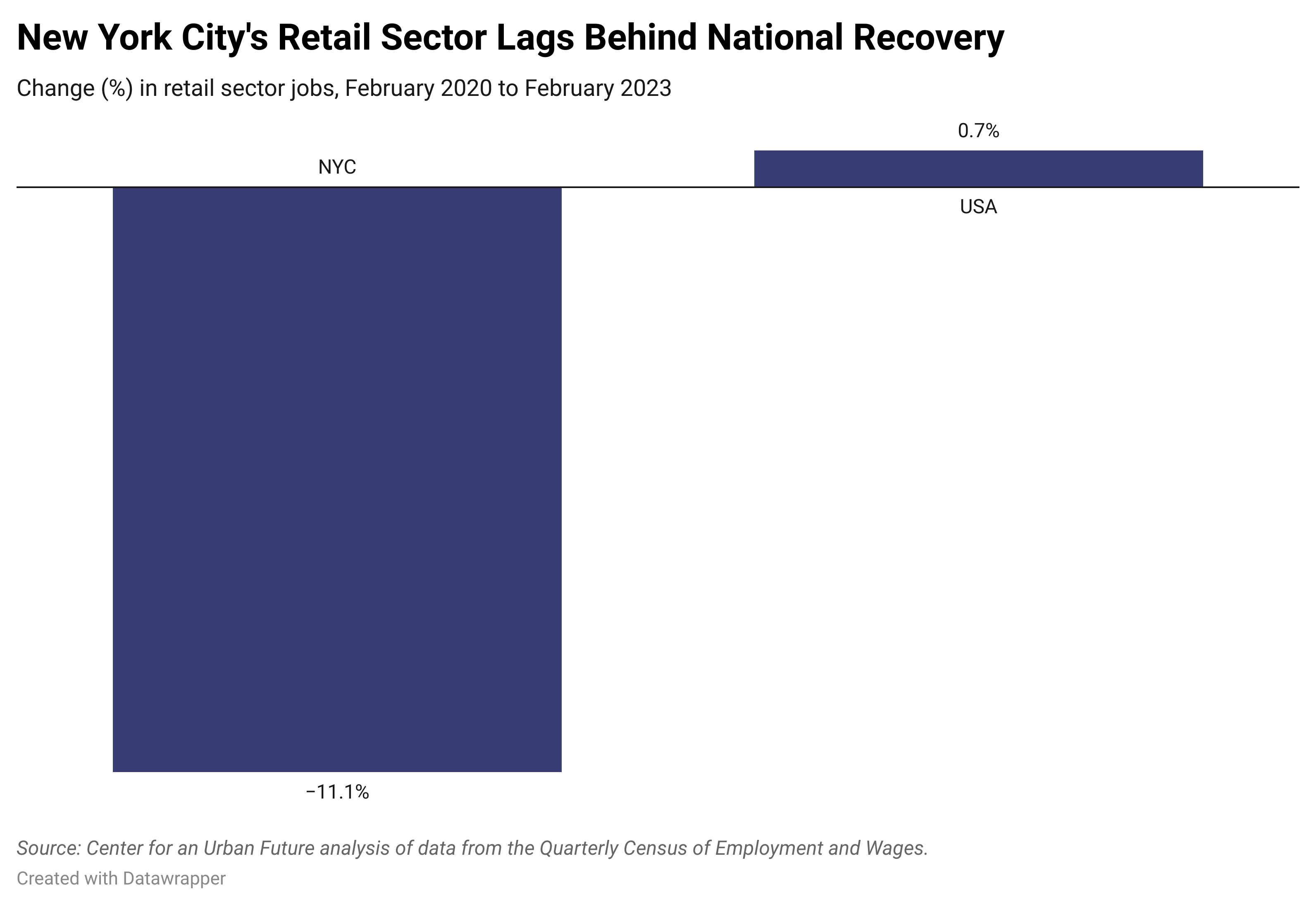

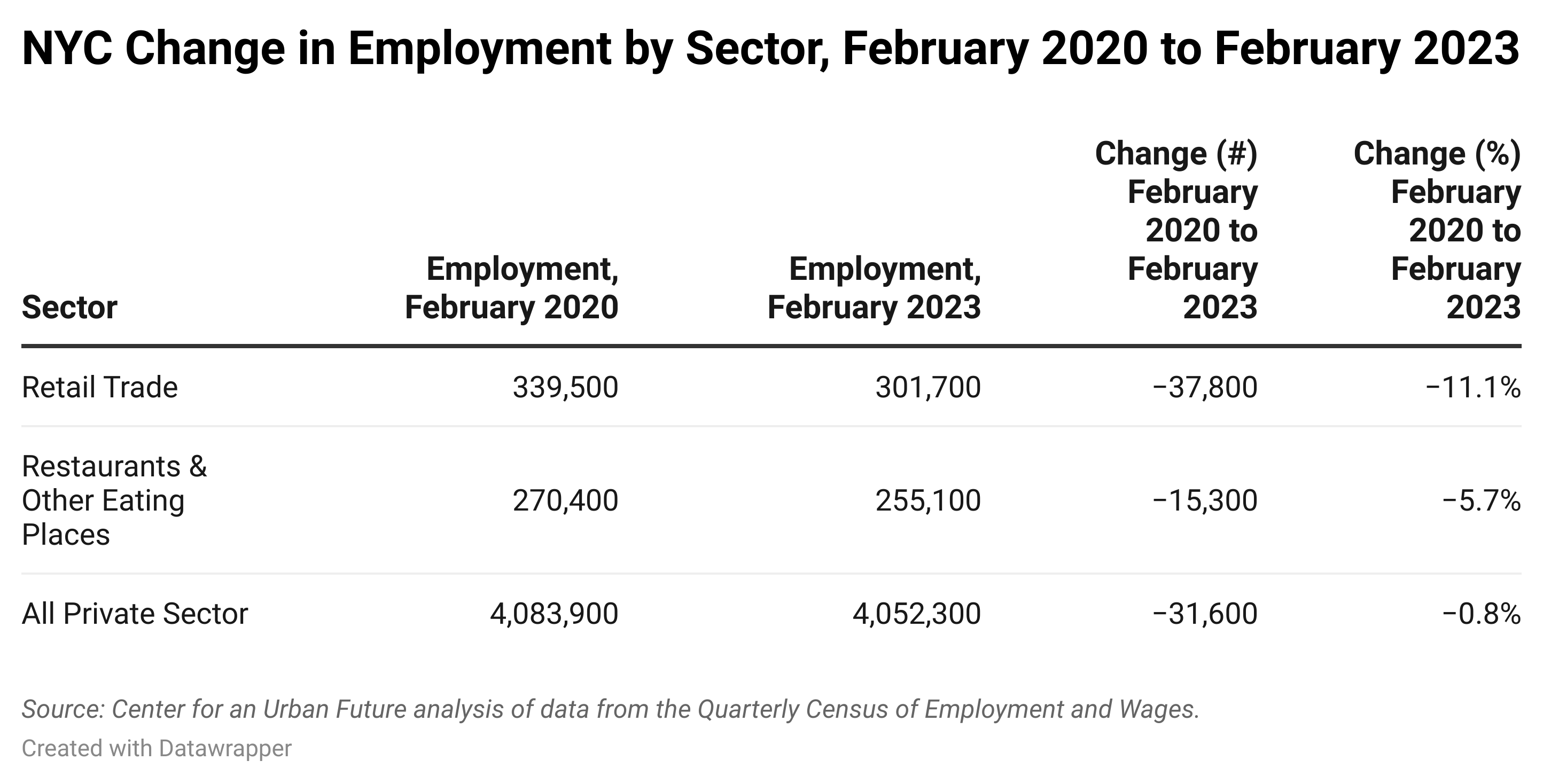

While the city’s overall economy has almost fully recovered all jobs lost during the pandemic—private sector employment is now down by just 0.8 percent from its pre-pandemic total—the city’s retail sector still has 11.1 percent fewer jobs than it did in February 2020.1 The retail sector’s jobs recovery has also lagged behind other face-to-face industries that were hit hard during the pandemic, including restaurants (which are still down from pre-pandemic employment numbers, but by just 5.7 percent).

A combination of factors is likely contributing to the retail sector’s stalled employment recovery, including the rapid growth of online shopping, the increasing adoption of automation by retailers, the slow return of office workers, and the sharp drop in the city’s population.

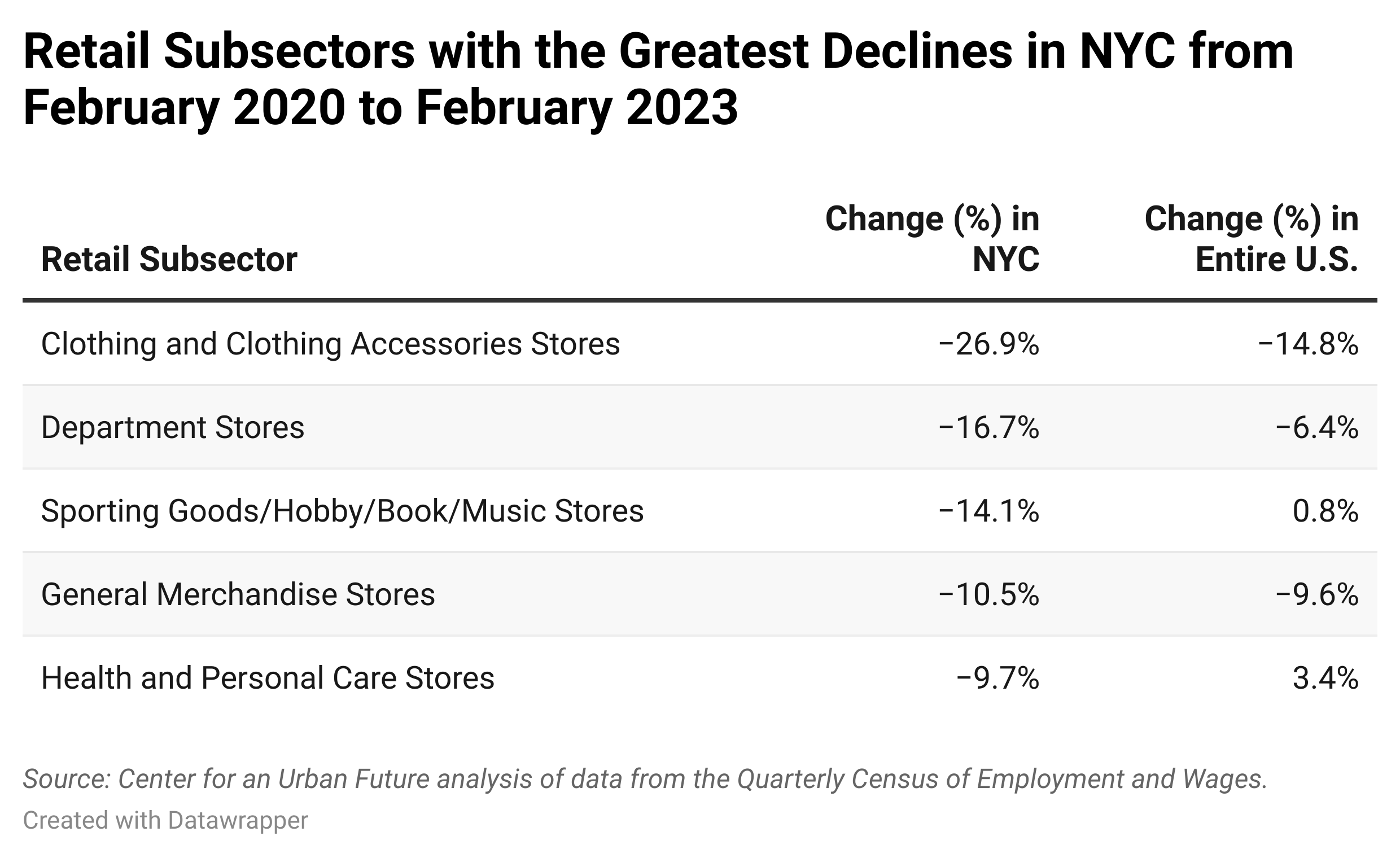

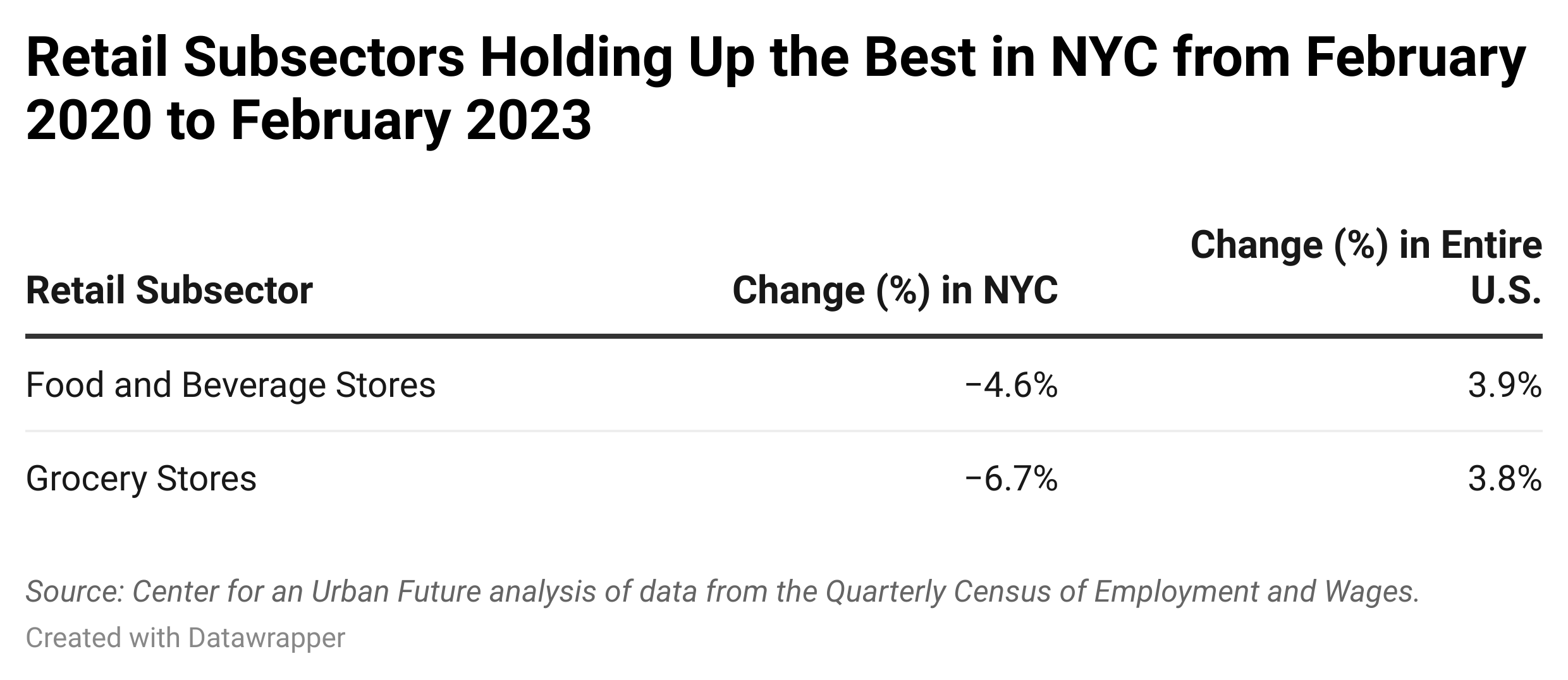

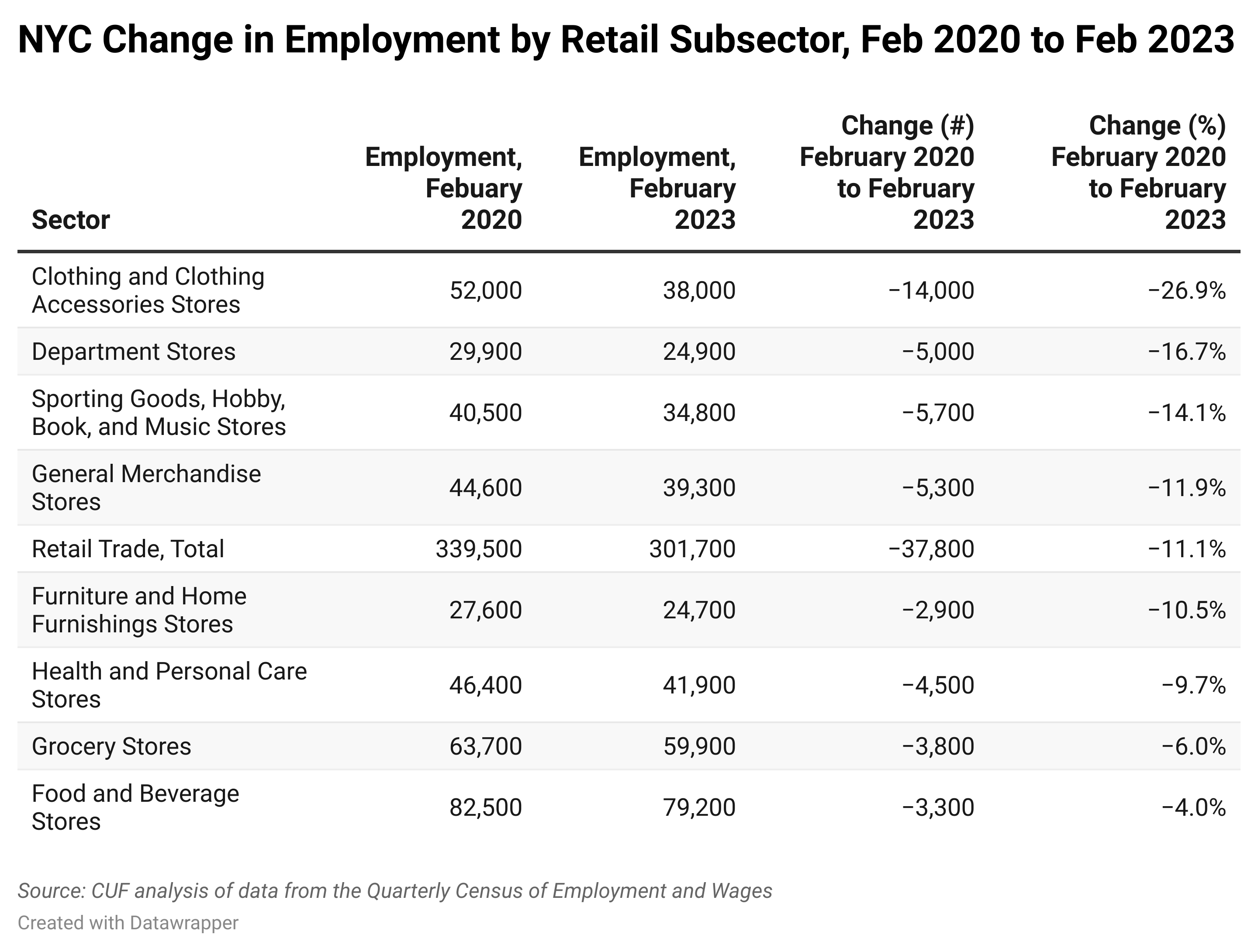

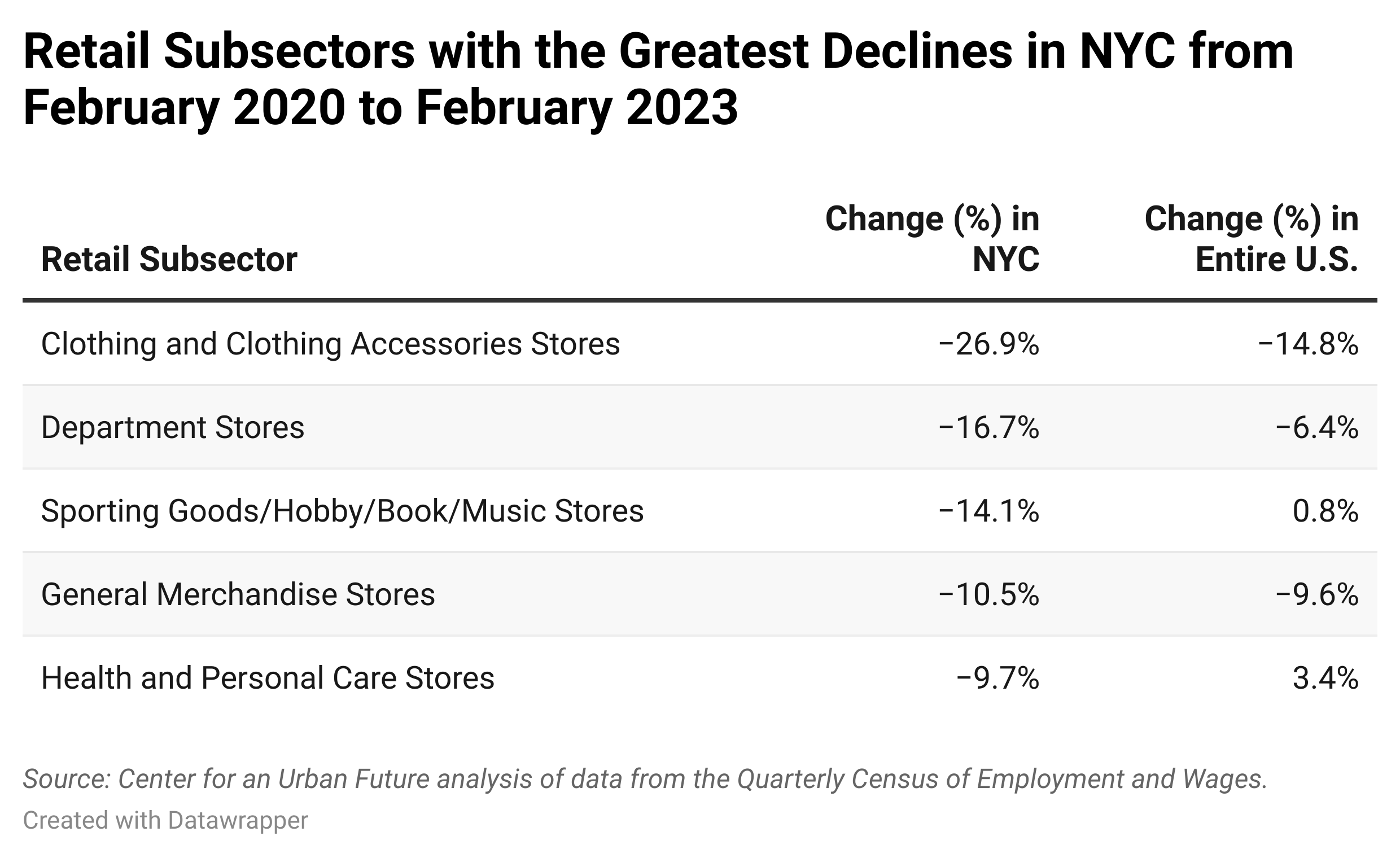

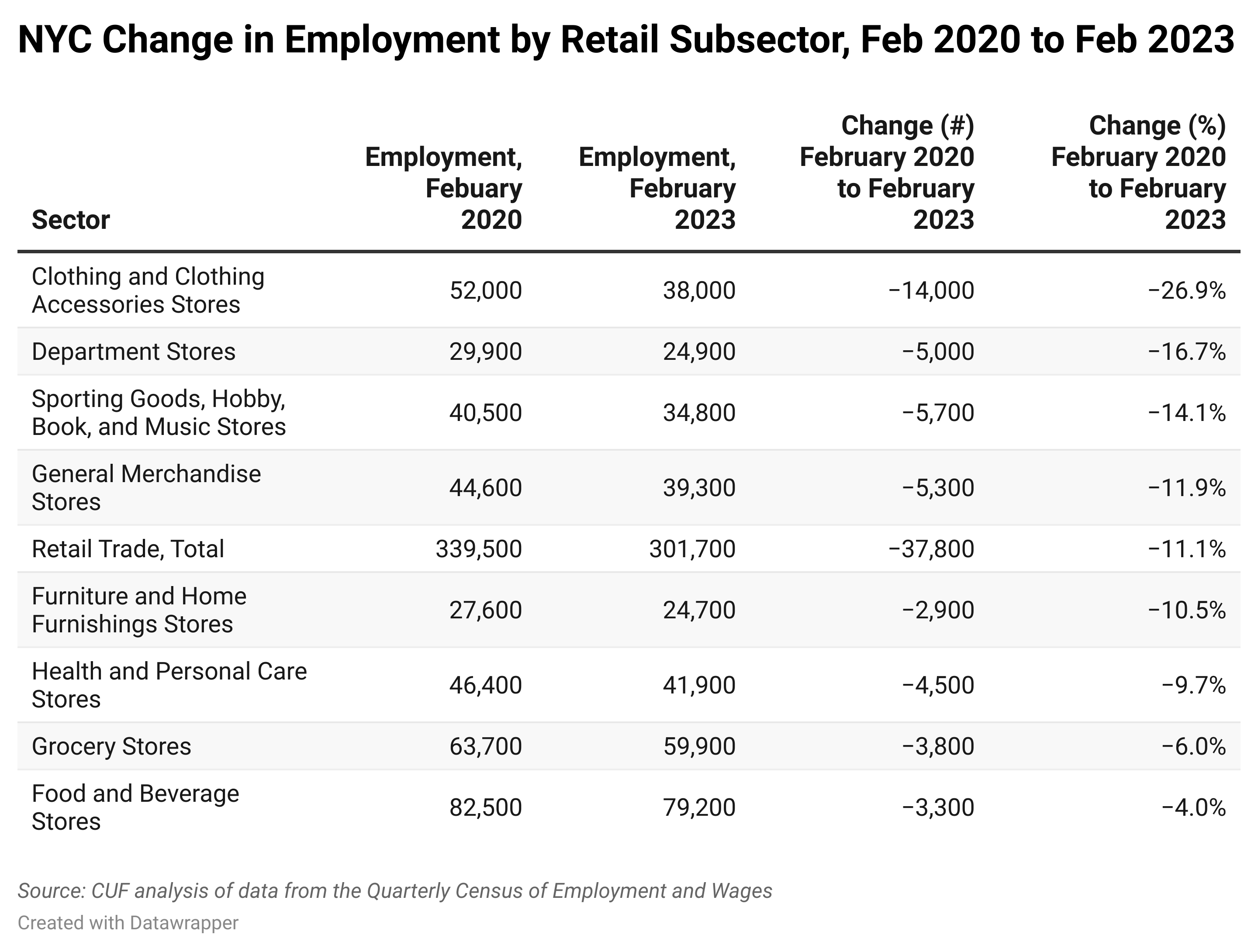

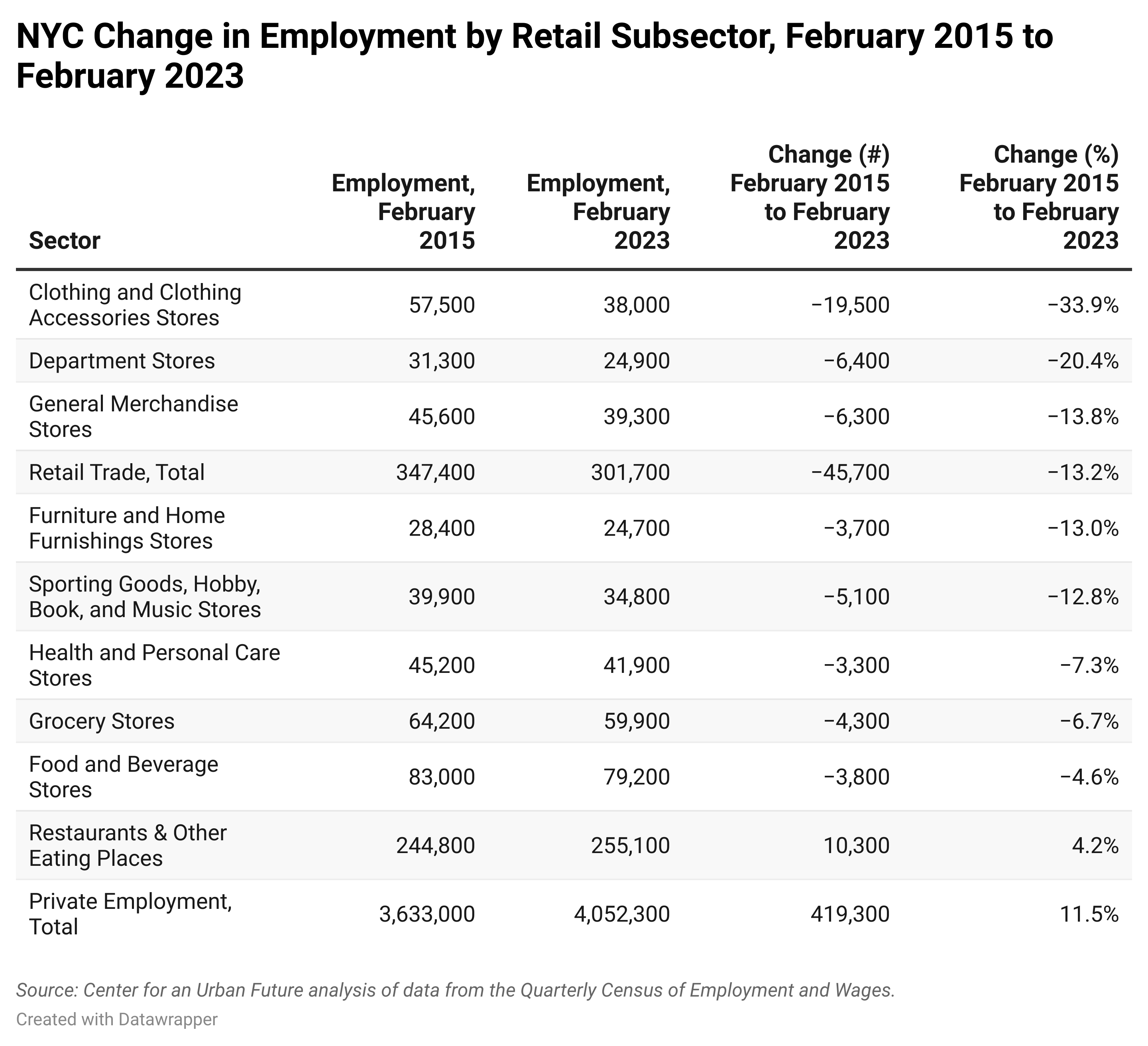

The impact of e-commerce appears clear. Every major retail subsector is well below pre-pandemic employment levels, with the largest job losses concentrated among stores that sell clothing, accessories, sporting goods, and other merchandise. Indeed, the three worst-performing retail subsectors between February 2020 and February 2023 were all merchandise retailers: 1) Clothing and Clothing Accessories Stores, where jobs are down by 26.9 percent since February 2020; 2) Department Stores (down 16.7 percent); and 3) Sporting Goods, Hobby, Book, and Music Stores (down 14.1 percent). In comparison, the two retail subsectors that have held up the best are food-related: Food and Beverage Stores (with jobs down 4 percent since February 2020), and Grocery Stores (down 6 percent).

There are four other worrying trends that raise questions about the long-term future of New York City’s retail sector.

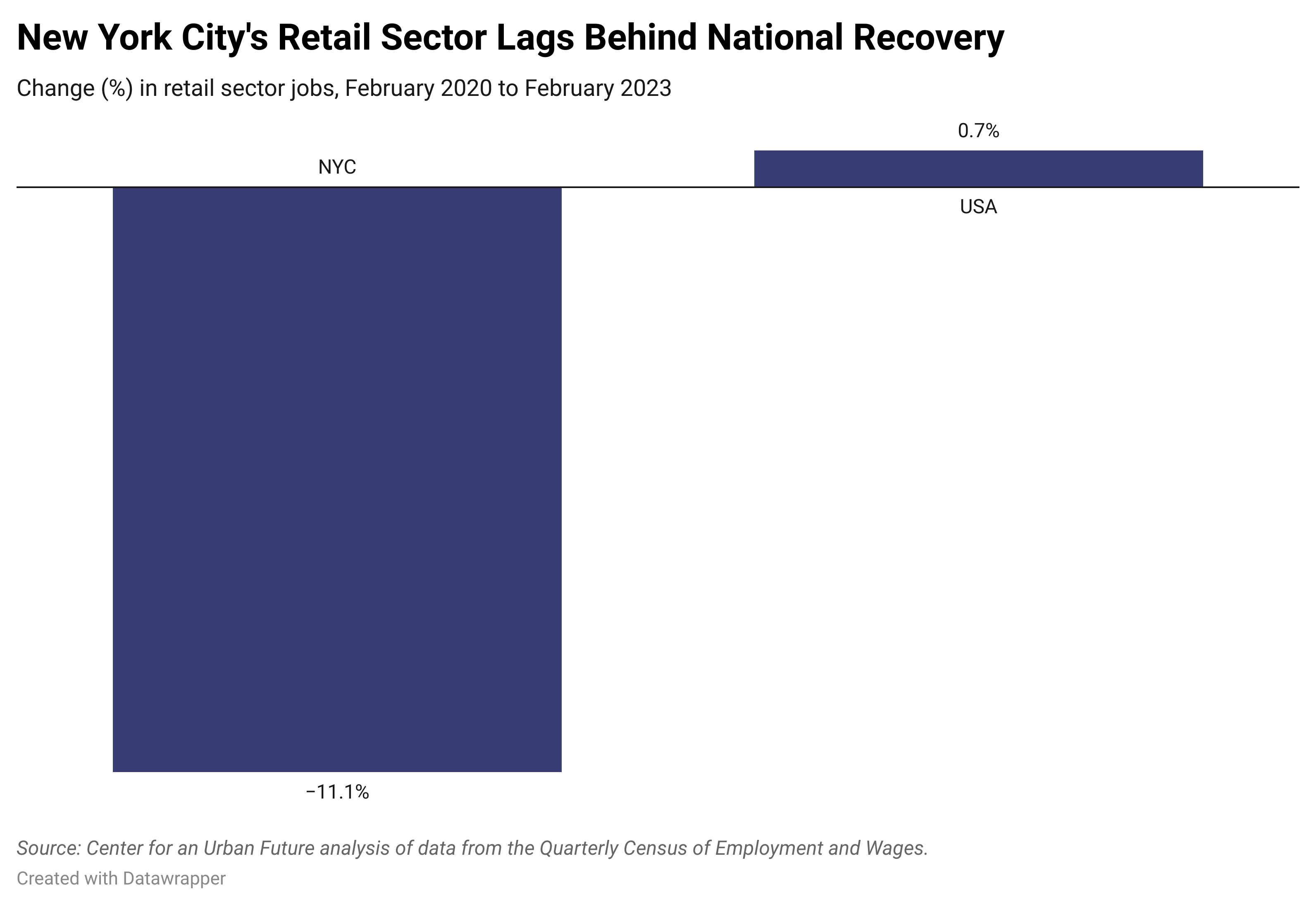

- New York’s retail sector has significantly underperformed the nation’s retail sector over the past three years. Indeed, retail jobs nationally have increased by 0.7 percent since immediately before the pandemic.2

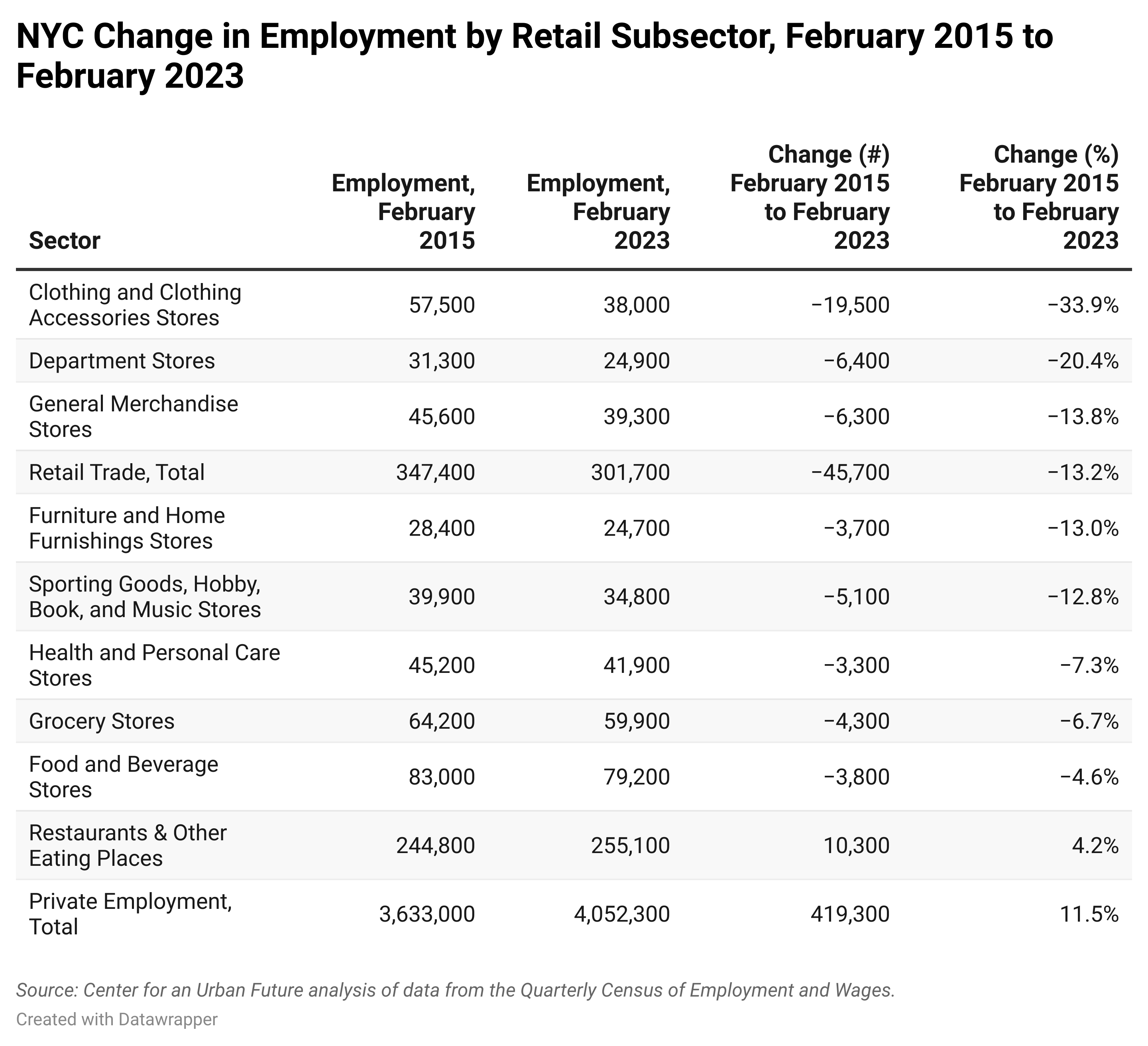

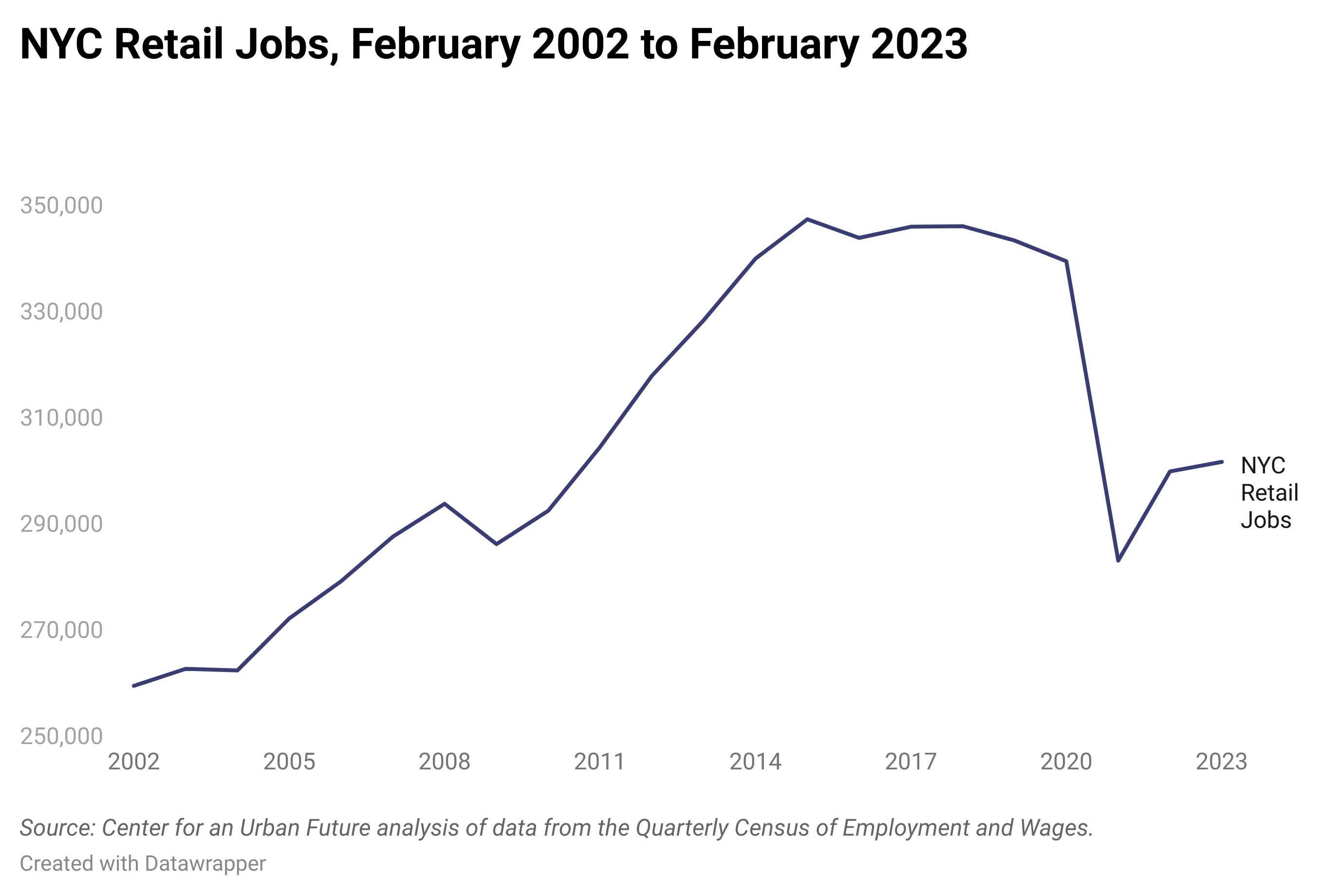

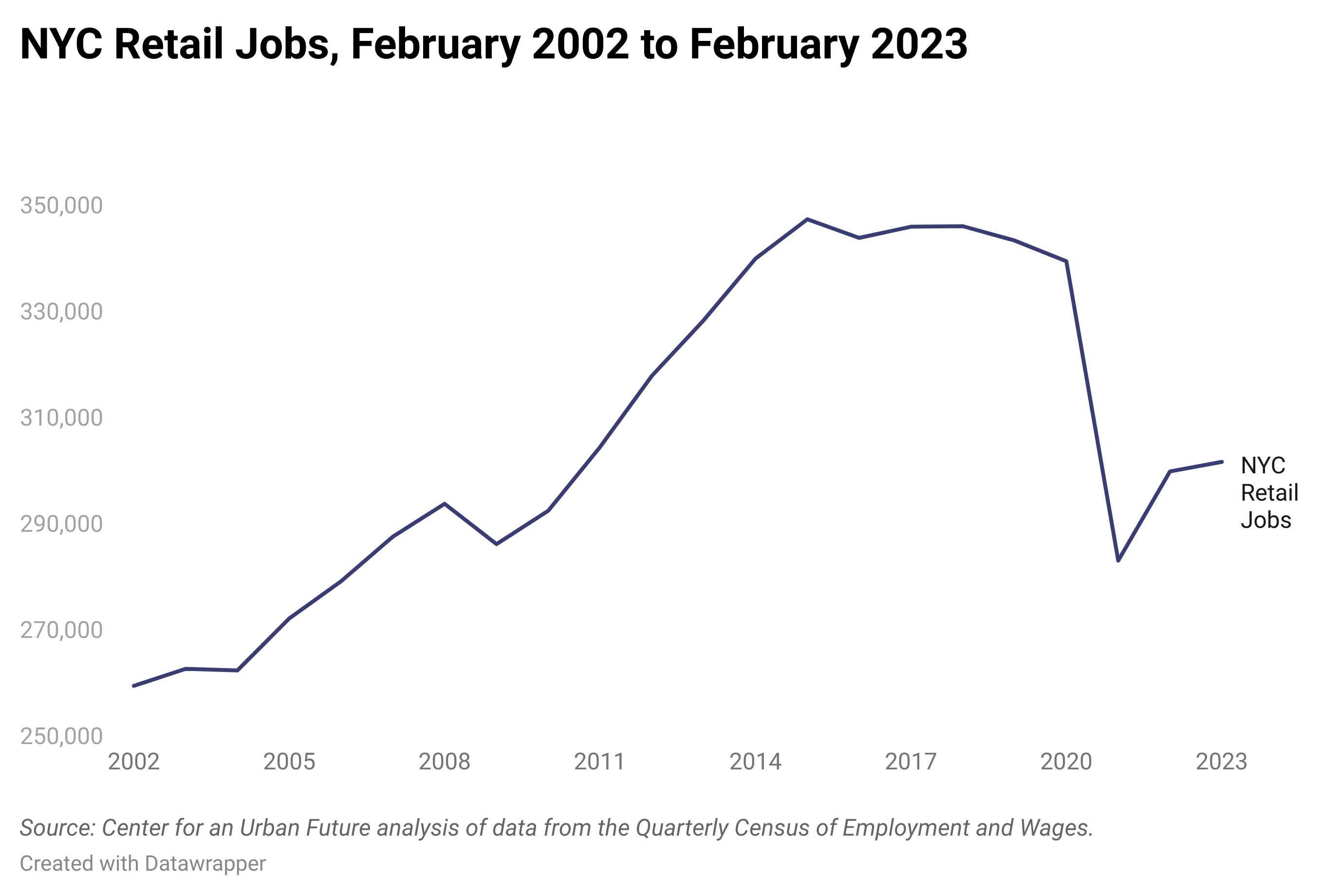

- Retail jobs in the city have been declining since 2015, suggesting that the sector’s troubles run deeper than the pandemic. In fact, while employment in the city’s retail sector declined by 37,800 between February 2020 and February 2023 (an 11.1 percent decline), it is down by 45,700 since February 2015—a 13.2 percent drop. During the same period (February 2015 to February 2023), total private sector employment in New York City increased by 11.5 percent, a net gain of 419,300 jobs.

- The average retail establishment in the city has nearly one fewer employee than it did before the pandemic—with the average size of retail businesses shrinking from 10.9 employees before the pandemic to 10.1 employees today. Although this may simply reflect owners reducing workforces to account for fewer customers, it could also be attributed to the growing adoption of automated check-out kiosks at stores from CVS and Target to Uniqlo and Home Depot (and a corresponding decline in staffing).

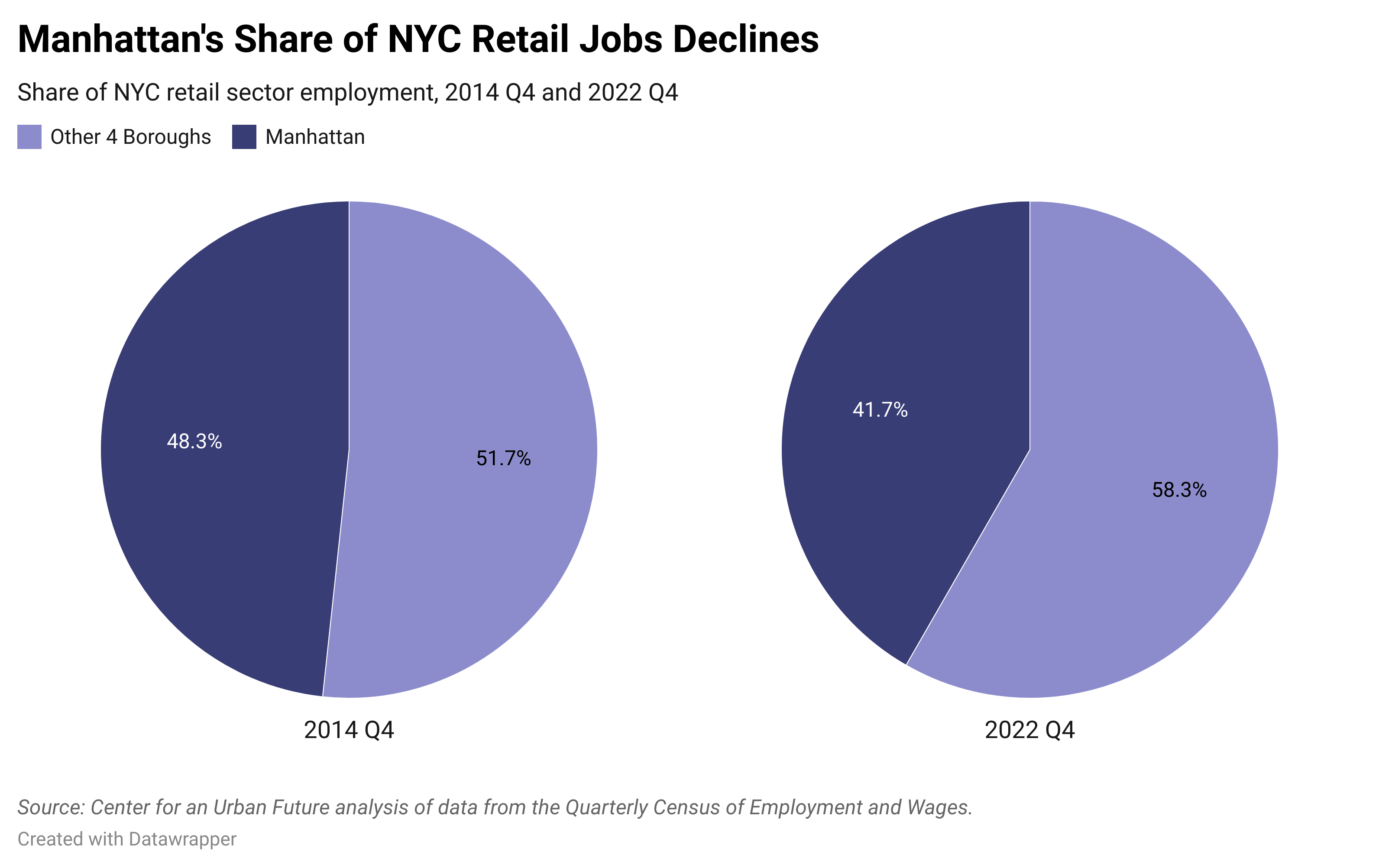

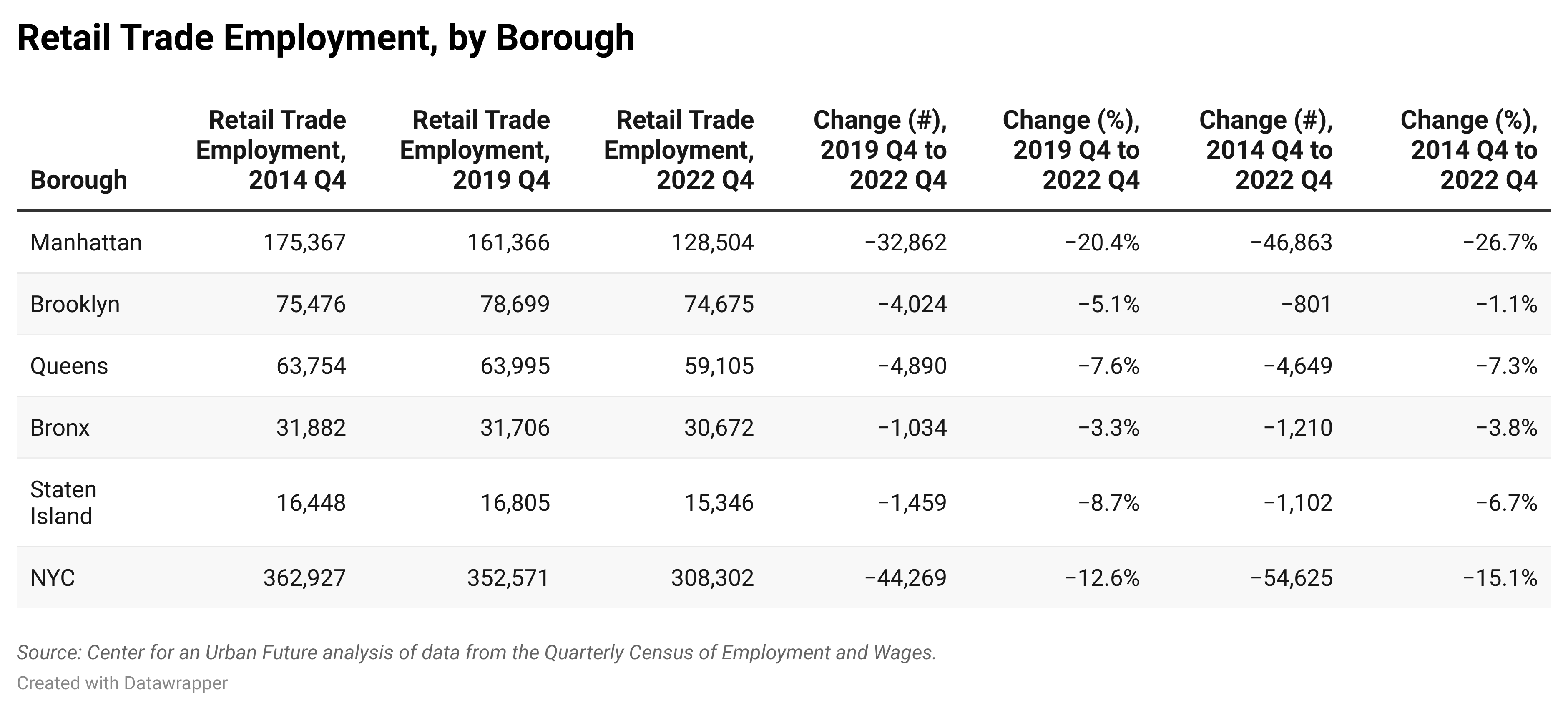

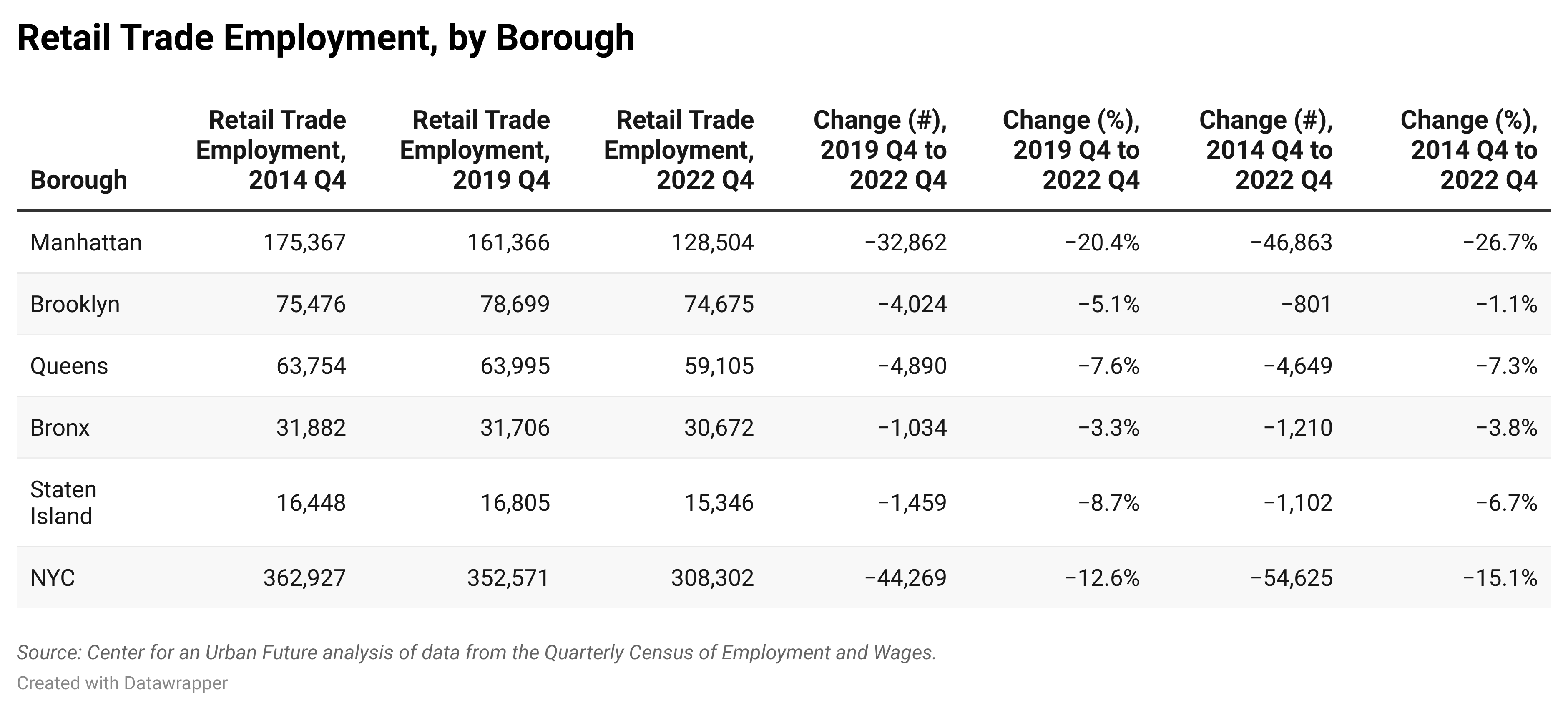

- While Manhattan has seen the slowest recovery in retail employment—not surprising given the precipitous decline in people working at offices in the city’s central business districts and the faster but not yet complete recovery of tourism—each of the other four boroughs also has fewer retail jobs than immediately before the pandemic. Manhattan lags the most, with 20.4 percent fewer retail jobs than its pre-pandemic total, but retail jobs are also down on Staten Island (8.7 percent decline), Queens (7.6 percent decline), Brooklyn (5.1 percent decline), and the Bronx (3.3 percent decline).3

The following are key findings from this analysis:

The following are key findings from this analysis:

Retail jobs have been slow to recover from the pandemic.

- The city’s retail sector still has 11.1 percent fewer jobs than immediately before the pandemic. In comparison, the city’s overall economy has almost fully recovered all jobs lost during the pandemic, with private sector employment now down by just 0.8 percent from its pre-pandemic totals.

- In February 2023, there were 37,800 fewer retail jobs in New York City than in February 2020. During the same period, total private sector employment was down by just 31,600 jobs, meaning that the losses in the retail sector account for more than 100 percent of all private sector job declines in New York City since the pandemic hit.

- Even the city’s hard-hit restaurant industry has come back twice as fast. Although the Restaurants & Other Eating Places industry has yet to recover all the jobs lost during the pandemic, restaurant jobs are down by just 5.7 percent since February 2020.

New York City’s retail sector is faring significantly worse than the nation’s.

- Whereas retail jobs in the city are still down by 11.1 percent since February 2020, retail jobs nationally have increased by 0.7 percent during the same period.

- In every major retail sub-sector—from clothing stores to grocery stores—jobs have recovered at a faster pace nationally than in New York City.

The largest job losses have been in stores that face the most direct competition from e-commerce.

- The worst-performing retail category in New York City has been Clothing and Clothing Accessories Stores, where jobs are down by 26.9 percent since February 2020. (Nationally, jobs in this subsector are down as well, but by just 14.8 percent.)

- The retail subsectors with the greatest declines in New York City (versus nationally):

- Clothing and Clothing Accessories Stores: - 26.9 % (-14.8%)

- Department Stores: -16.7% (-6.4%)

- Sporting Goods, Hobby, Book, and Music Stores: -14.1% (+0.8%)

- General Merchandise Stores: -11.9% (+4.2%)

- Furniture and Home Furnishings Stores: -10.5% (-9.6%)

- Health and Personal Care Stores: -9.7% (+3.4%)

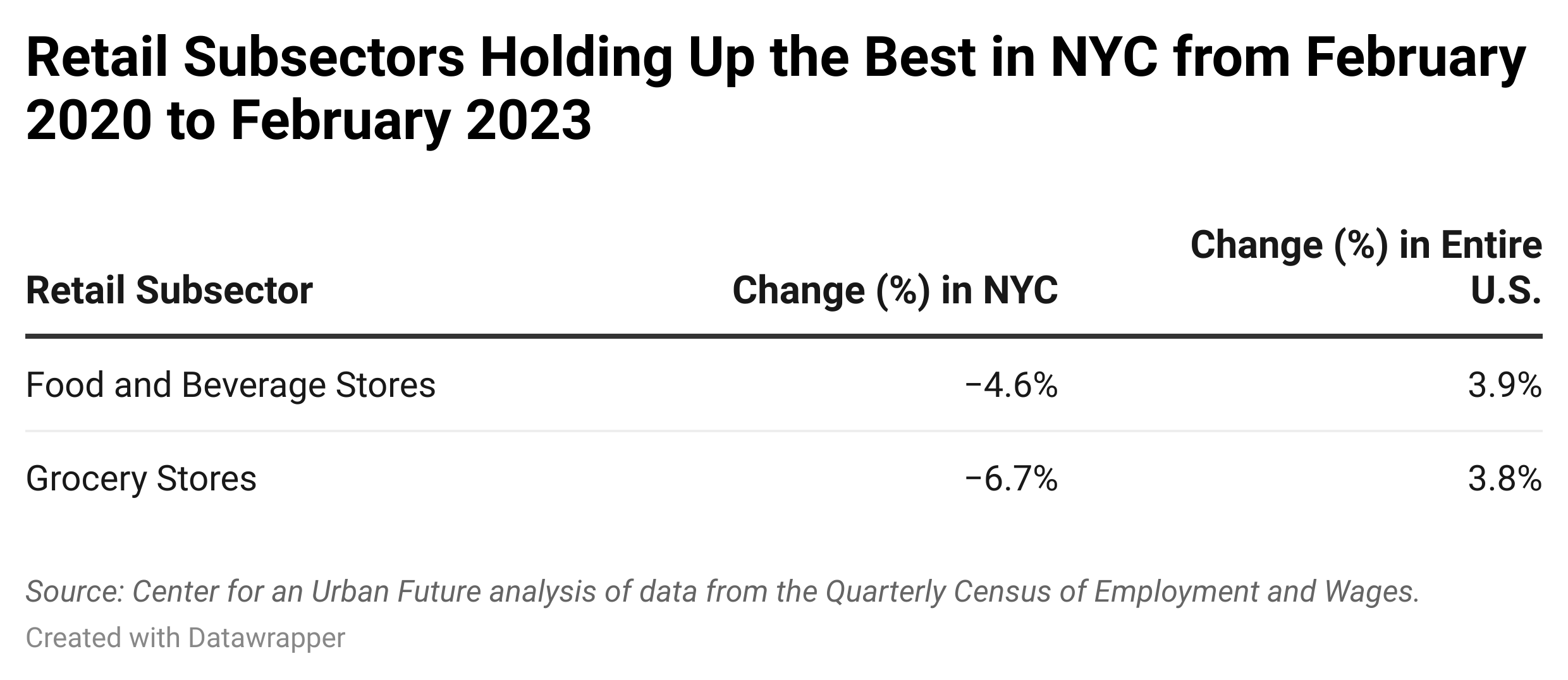

- The retail subsectors that have held up the best in New York City are those that involve food (versus nationally)

- Food and Beverage Stores: -4.6% (+3.9%)

- Grocery Stores: -6.7% (+3.8%)

New York’s retail sector’s problems run deeper than the pandemic. In fact, retail jobs in the city have been declining for eight years.

- While employment in the city’s retail sector has declined by 37,800 since February 2020, it is down by 45,700 since February 2015—a 13.2 percent drop. During the same period (February 2015 to February 2023), total private sector employment in New York City increased by 11.5 percent, a net gain of 419,300 jobs.

- For several decades until 2015, retail jobs had been steadily increasing. Between February 1993 (30 years ago) and February 2015, the city’s retail sector grew by 118,500 jobs—a 51.8 percent increase, going from 228,900 jobs in February 1993 to 347,400 in February 2015. Since February 2003 (20 years ago), the city’s retail sector added 84,700 jobs through February 2015, a 32.2 percent jump. But since 2015, retail jobs in the city have plummeted by 45,700 (a 13.2 percent decline), going from 347,400 in February 2015 to 301,700 in February 2023.

- The following retail categories have registered the greatest declines since retail jobs peaked in February 2015:

- Clothing and Clothing Accessories Stores: -33.9 percent (a loss of 19,500 jobs, from 57,500 in February 2015 to 38,000 in February 2023)

- Department Stores: -20.4 percent (a loss of 6,400 jobs, from 31,300 to 24,900)

- General Merchandise Stores: -13.8 percent (a loss of 6,300 jobs, from 45,600 to 39,300)

- Furniture and Home Furnishings Stores: -13 percent (a loss of 3,700 jobs, from 28,400 to 24,700)

- Sporting Goods, Hobby, Book, and Music Stores: -12.8 percent (a loss of 5,100 jobs, from 39,900 to 34,800)

- Health and Personal Care Stores: -7.3 percent (a loss of 3,300 jobs, from 45,200 to 41,900)

- Grocery Stores: -6.7 percent (a loss of 4,300 jobs, from 64,200 to 59,900)

- Food and Beverage Stores: -4.6 percent (a loss of 3,800 jobs, from 83,000 to 79,200)

Manhattan is furthest behind, but all five boroughs have yet to fully recover retail jobs lost during the pandemic.

- In Manhattan, there are still 32,862 fewer retail jobs since before the start of the pandemic, a decline of 20.4 percent—from 161,366 in the fourth quarter of 2019 to 128,504 in the fourth quarter of 2022.

- In Queens, there are now 4,890 fewer jobs since before the pandemic, a 7.6 percent decline—from 63,995 to 59,105.

- In Brooklyn, there are still 4,024 fewer jobs since before the pandemic, a 5.1 percent decline—from 78,699 to 74,675.

- In Staten Island, there are 1,459 fewer jobs since before the pandemic, an 8.7 percent decline—from 16,805 to 15,346.

- In the Bronx, there are 1,034 fewer jobs since before the pandemic, a 3.3 percent decline—from 31,706 to 30,672.

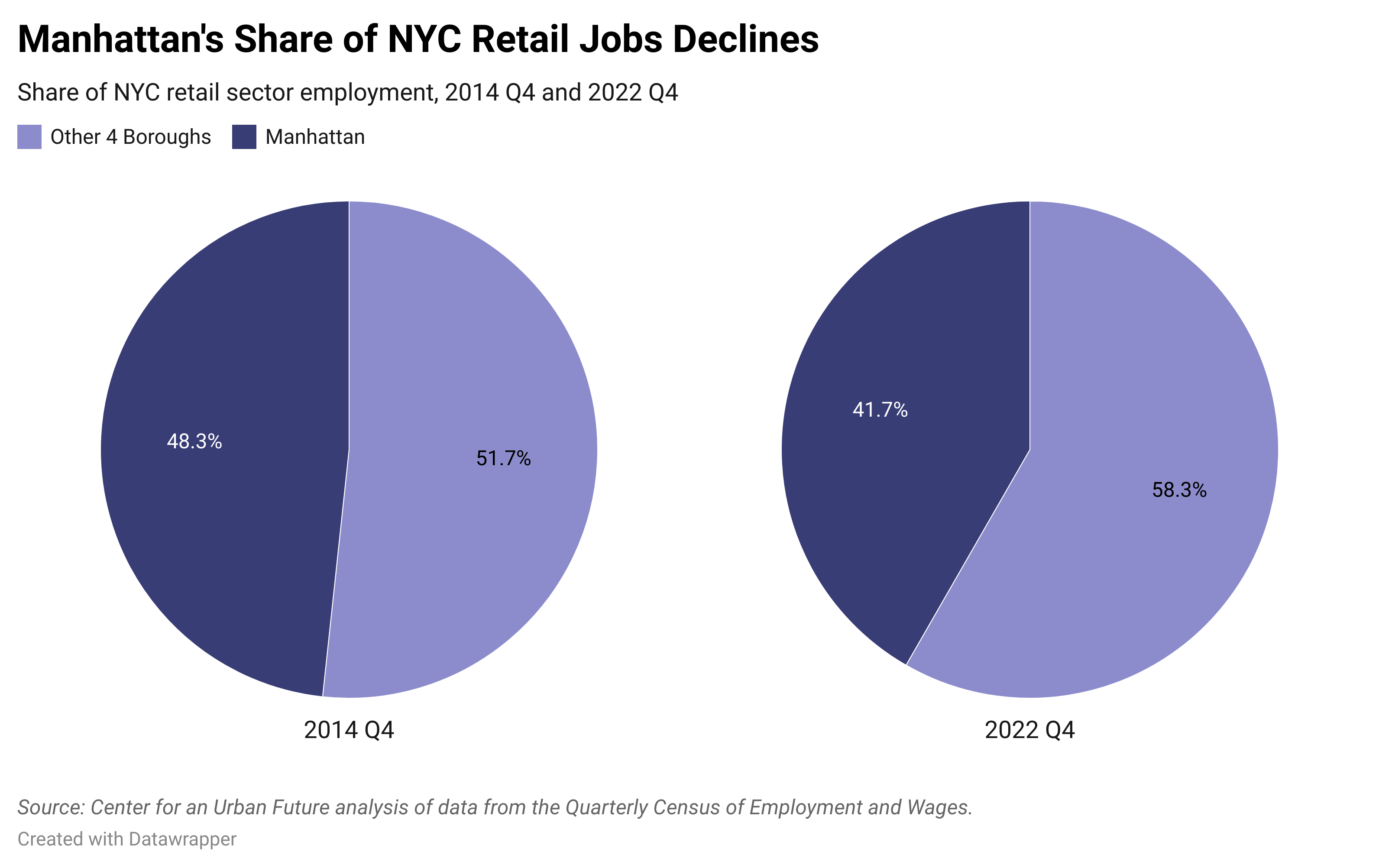

Manhattan’s share of all retail jobs citywide has fallen precipitously.

- In the fourth quarter of 2014, Manhattan was home to 48.3 percent of all retail jobs in the city. By the fourth quarter of 2022, Manhattan’s share had fallen to 41.7 percent.

The number of employees per retail business has declined in every borough.

- In Manhattan, the average size of each retail firm has shrunk from 15.4 employees in the fourth quarter of 2019 to 13.4 employees in the fourth quarter of 2022.

- In Brooklyn, the number of employees at the average retail establishment has declined from 8.21 to 8.1.

- In Queens, the number of employees at the average retail establishment has declined from 8.9 to 8.6.

- In Staten Island, the number of employees at the average retail establishment has declined from 12.8 to 12.4.

- In the Bronx, the number of employees at the average retail establishment has barely changed, declining from just over 8.48 to just under 8.48.

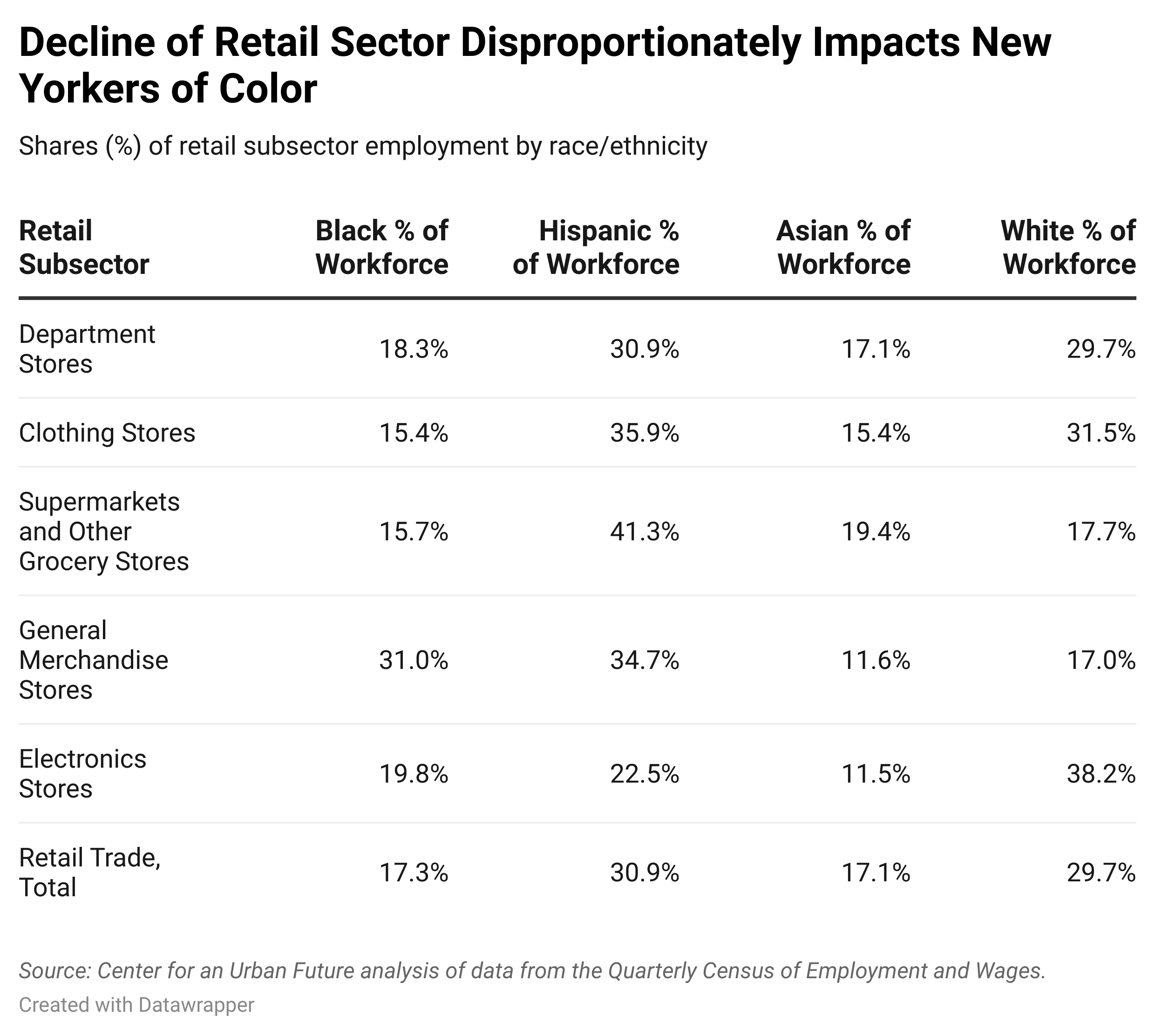

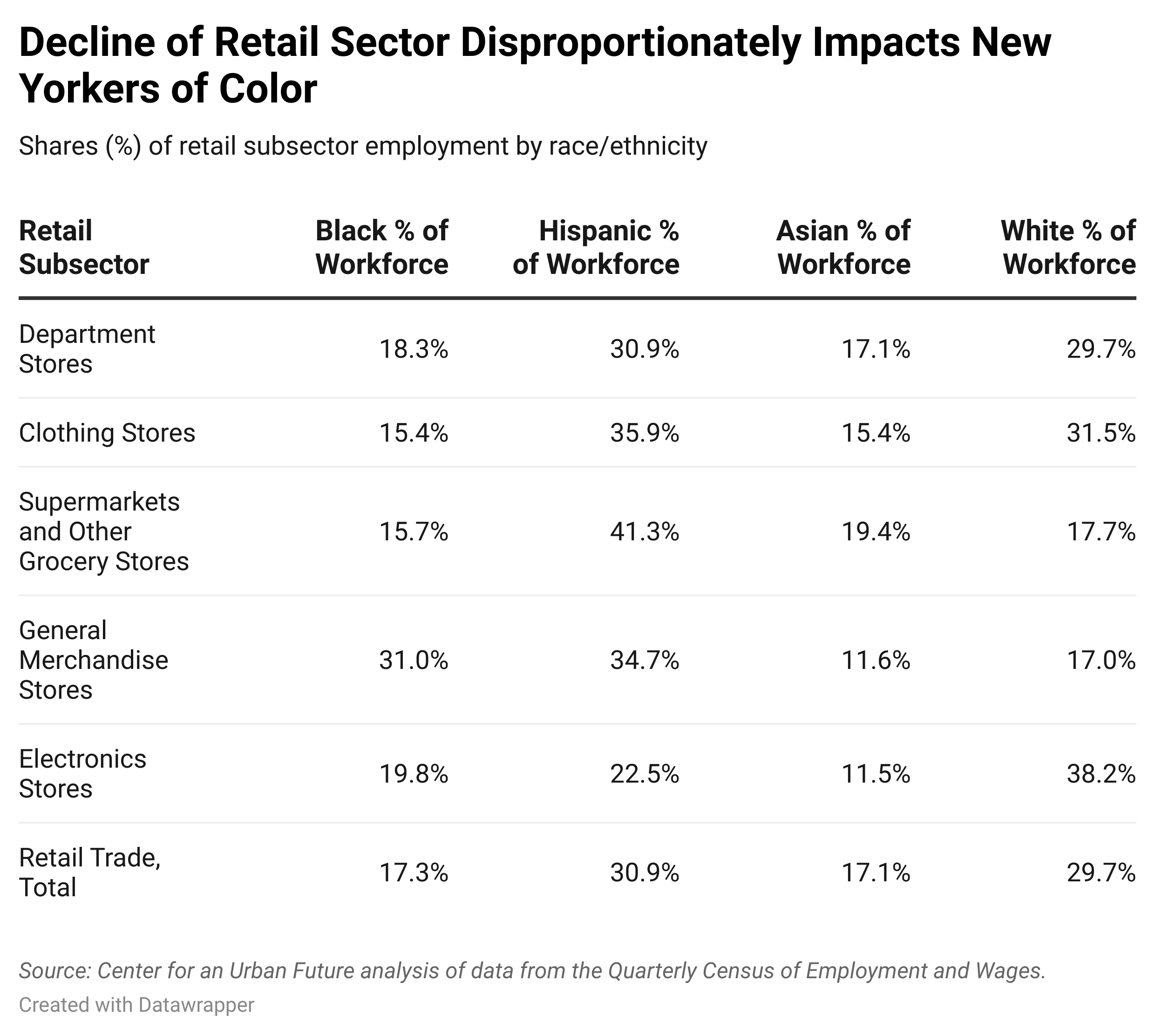

The city’s retail job losses are likely disproportionately impacting New Yorkers of color. Indeed, the workforce in most retail subsectors is predominantly non-white4:

- Retail: 70.3% non-white (17.3% Black, 30.9% Hispanic, 17.1% Asian, 29.7% white)

- Department Stores: 73% non-white (18.3% Black, 35.9% Hispanic, 15.4% Asian, 27.3% white)

- Clothing Stores: 68% non-white (15.4% Black, 30.1% Hispanic, 17.4% Asian, 31.5% white)

- Supermarkets and other grocery stores: 82.3% non-white (15.7% Black, 41.3% Hispanic, 19.4% Asian, 17.7% white)

- General Merchandise Stores: 83.0% non-white (31.0% Black, 34.7% Hispanic, 11.6% Asian, 17% white)

- Electronics Stores: 61.8% non-white (19.8% Black, 22.5% Hispanic, 11.5% Asian, 38.2% white)

The retail sector decline is disproportionately affecting New Yorkers who live outside of Manhattan.

- 81 percent of the New Yorkers working in retail live in Brooklyn, the Bronx, Queens, or Staten Island, even though nearly half (42 percent) of retail jobs are located in Manhattan.

- Bedford Park/Fordham North/Norwood and Richmond Hill/Woodhaven have the largest share of residents working in the retail sector (13.4 percent and 13.3 percent of the workforce are employed in retail, respectively), followed by Pelham Parkway/Morris Park (12.4 percent), Sheepshead Bay/Gerritsen Beach/Homecrest (11.8 percent), Prospect Heights/Crown Heights North (11.2 percent), and Howard Beach/Ozone Park (11.1 percent).

- In raw numbers, Prospect Heights/Crown Heights North has the most residents employed in the retail sector (10,644).

The continued job declines in retail also disproportionately affects young adults.

Approximately 20.5 percent of New York City’s retail workforce is under the age of 25, according to the Center for an Urban Future’s analysis of labor market demographic data from Lightcast.

The Way Forward

New York has largely made up for the retail sector’s extended job losses with new employment growth in tech, health care, finance, and a handful of other industries, but a permanent loss of roughly 40,000 retail jobs would disproportionately impact New Yorkers of color. The retail sector’s troubles have almost certainly contributed to the widening gap in unemployment among Black and white New Yorkers—10.4 percent compared with 2.5 percent.

To address this employment crisis, city and state policymakers should invest in workforce training and continuing education programs that can help retail workers transition into other industries.

City leaders should also explore policies that could help boost in-store shopping. Nothing would help more than significantly increasing housing development across the five boroughs, which would result in thousands of new residents and an expanded customer base for struggling retailers. More immediately, the city can expand efforts to boost foot traffic along major commercial corridors through public art installations, streetscape improvements, and support for local cultural events and festivals. New York policymakers should also consider programs that incentivize New Yorkers to shop in-person, such as a sales tax break or special discount program. For example, New York ought to consider something similar the United Kingdom’s “Eat Out to Help Out” scheme, which provided a government-backed 50 percent discount for dining out at local restaurants on Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday nights in August—but for spending at local retailers. Similarly, the “Buy Local Bonus” program in San Luis Obispo, California, provided shoppers with a gift card to one of 147 local retailers in exchange for submitting a receipt for $100 or more from a local business.

Finally, city economic development officials should do more to help make local retailers more competitive in the ecommerce era. The city can help more small and mid-sized retailers get online, sell directly to consumers, and connect with Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs) to make the investments needed to improve their sales and margins and help strong small retailers scale up.

Appendix

Endnotes

1 CUF analysis of data from New York State Department of Labor, Current Employment Statistics, February 2020 to February 2023, Not Seasonally Adjusted.

2 CUF analysis of data from U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, February 2020 to February 2023.

3 All analysis of jobs in NYC’s five boroughs from NY State Labor Department, Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, Q4 2019 to Q4 2022.

4 New York City's retail workforce is 70.3 percent non-white (17.3% Black, 30.9% Hispanic, 17.1% Asian, 29.7% white; another 5 percent self-identify as two or more races or another race). In each of these industries, workers who identify as two or more races and/or another race make up the differece between the sum of all Black, Hispanic, Asian, and white workers, and 100 percent of all workers in that industry.

The following are key findings from this analysis:

The following are key findings from this analysis: