New Yorkers have watched the world of work transform over the past generation, as automation, outsourcing, contingent labor, online retail, and other powerful forces undermined one traditional springboard to the middle class after another. New York’s human capital policies, on the other hand, have mostly stayed the same. The widening gap creates a unique opportunity for the state to help more New Yorkers—including its nearly two million working poor families—access a path to better jobs and family-sustaining wages.

That opportunity is now. Governor Andrew Cuomo has proposed a package of reforms to invest in large-scale workforce training initiatives and direct those initiatives to respond to the real needs of employers across the state. The governor’s proposal, which aims to invest $175 million in workforce training initiatives, addresses the growing need for training and education pathways that can help New York residents gain skills relevant to growing fields, while earning credit toward a postsecondary credential.

It is vital that policymakers fully support a new statewide investment in workforce development. This policy brief, funded by the Working Poor Families Project, details why this investment matters so much for New York’s workforce and economy, and outlines a handful of specific ideas for ensuring that new programs reach as many New Yorkers as possible with the most effective tools. This means providing more resources for traditional job training programs and emerging STEM initiatives that help New Yorkers develop the skills needed to access well-paying technology jobs. At the same time, an effective strategy will require increased investment in adult education and bridge programs, so the many New Yorkers with limited math and literacy skills can get a boost into career training. New York should also follow the lead of more than a dozen other states and develop a data clearinghouse to help ensure that the state’s new workforce dollars go to effective programs that result in decent jobs.

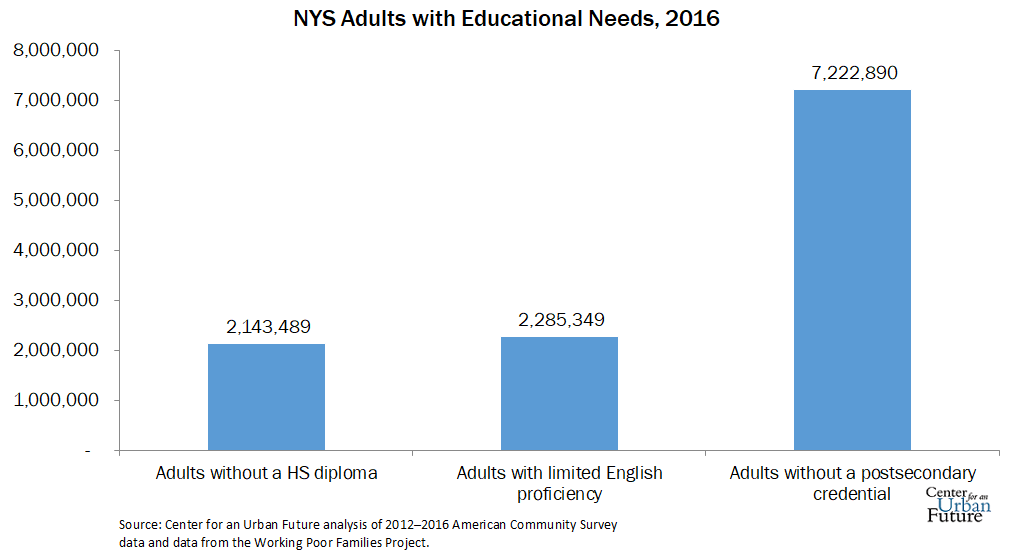

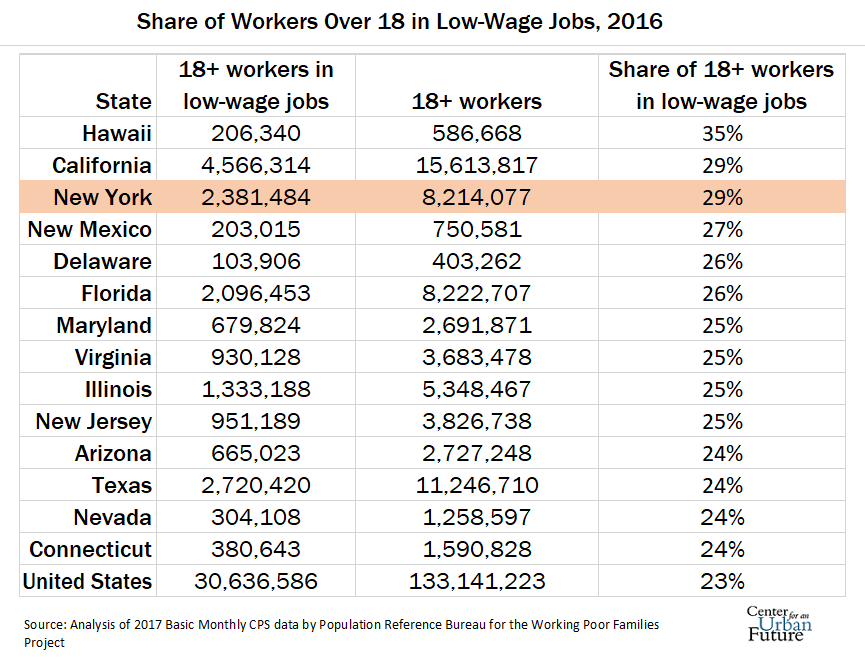

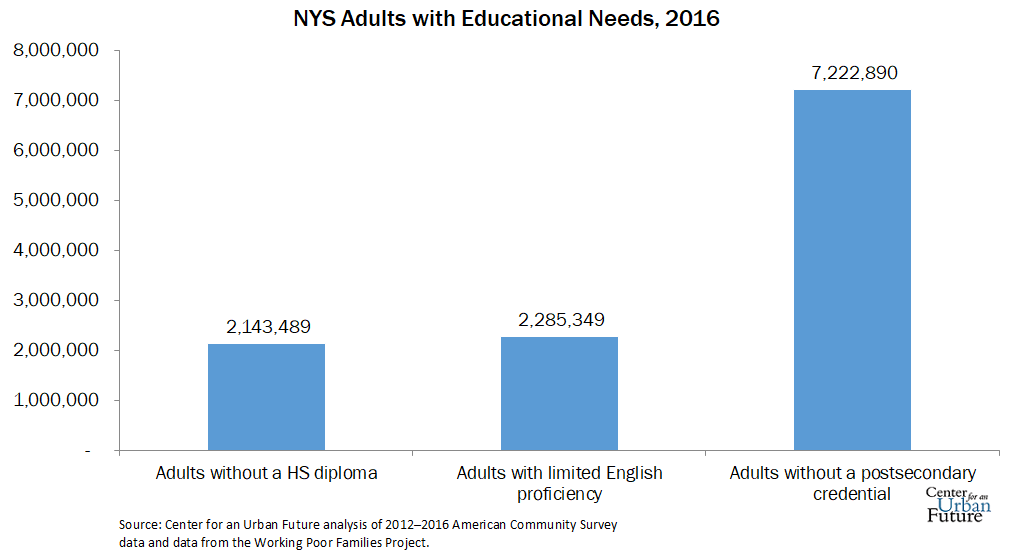

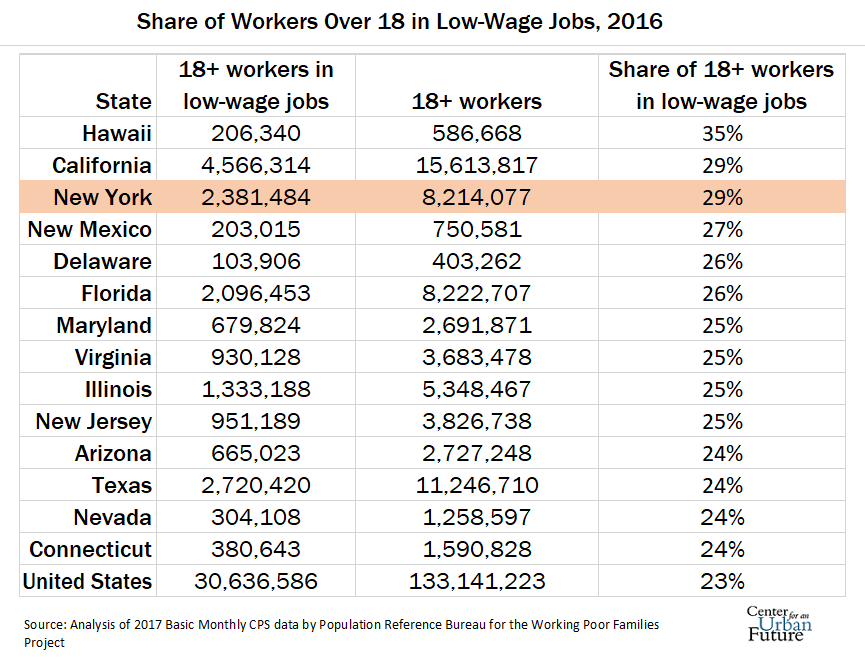

To get ahead in today’s economy, New Yorkers need skills and credentials that go beyond a high school diploma—and the demand has never been greater. Nearly 30 percent of all adult workers in New York are in low-wage jobs—the third-highest share of any state.1 Meanwhile, more than 7 million adult New Yorkers lack any form of postsecondary credential, according to data from the Working Poor Families Project, including more than 2 million without even a high school diploma.2

At the same time, a growing number of New York State employers are facing workforce shortages, especially when it comes to middle-skill jobs. In May 2016, the New York State Department of Labor reported on six important sectors that are projecting future labor shortages—including healthcare, skilled trades, and STEM occupations—and concluded that “these worker shortages are expected to worsen in the coming years.” The deficit is driven, in part, by the aging of the state’s labor force. Today, more than 22 percent of the state’s workforce is over age 55, including 400,000 workers in the healthcare sector alone.3 As nearly one-quarter of the state’s workforce heads toward retirement over the coming decade, companies across the state will be scrambling to replace these workers.

New York State faces a critical opportunity to upgrade and expand its statewide workforce development system, with broad-based benefits for millions of jobseekers and the economy. These new resources can invigorate existing workforce development infrastructure—including nearly a dozen state agencies, ten Regional Economic Development Councils, 33 local workforce development areas, 36 community colleges, and a kaleidoscope of community-based organizations—and scale up services in every corner of the state. This brief lays out the case for new statewide investments in workforce development and makes several recommendations to ensure that these investments are as far-reaching and effective as possible, including an increase in resources for adult basic education, ramped-up bridge programs, and accountability through better data.

Why New York needs to up its investment in effective workforce training

Governor Cuomo’s workforce plan, announced in January, is the most ambitious proposal in years aimed at bolstering the state’s workforce development capabilities. First, the plan proposes to invest $175 million into workforce development through the state’s Regional Economic Development Councils, of which $150 million is new and $25 million is repurposed from existing workforce funding streams. Second, the plan establishes a new Office of Workforce Development to provide a “focal point of accountability and coordination for all workforce training programs for the state.”4 Third, the plan creates an online portal to offer information and access to services, available to both workers and businesses. Finally, the plan calls for advanced data analytics capacity that will enable regional economic planners to develop sector-based workforce development plans.

A bold new investment in workforce development can capitalize on a major opportunity to strengthen the state’s economy while connecting New Yorkers with careers. As New York State has transformed from an industrial economy to a knowledge-based economy over the past two decades, the demand for effective workforce training and skills-building has exploded. Widespread use of automation and outsourcing has wiped out most of the state’s factories, where generations of New Yorkers once obtained good-paying jobs out of high school. Indeed, between 1991 and 2005, New York lost more than 340,000 blue-collar good jobs attainable without a bachelor’s degree.5 At the same time, new opportunities are growing—in fields from healthcare and construction to technology and design—but these jobs increasingly demand specialized skills beyond a high school diploma.

Today, education beyond the high school level makes career aspirations possible, and it is increasingly what employers need from job applicants. Along with high school diplomas and postsecondary credentials, employers seek workers with a blend of basic skills such as fluent reading and writing, math ability, English literacy, and computer savvy, as well as specific vocational skills. Jobseekers with limited experience may also need a crash course in essential workplace skills, such as punctuality, collaboration, and problem-solving. Without any one of these skills, workers end up left behind.

For some New Yorkers, the best option is a traditional four-year college degree, which is linked to significant increases in earnings. But for many others, especially working adults with families and responsibilities, that route can seem all but unattainable. Yet other educational and training pathways exist. An effective workforce development system opens opportunities to obtain postsecondary and industry-recognized credentials that are more than a high school diploma but less than a bachelor’s degree, leading to middle-skill jobs and higher earnings.

Roughly one in four jobs in New York falls in this category—including carpenters, paralegals, dental hygienists, and many more—and the New York State Department of Labor projects high growth for about 80 percent of these jobs over the next decade.6 This means that New York State is on track to add more than a quarter-million jobs that require either an associate’s degree, an apprenticeship, or some kind of certificate or certification.

Unfortunately, New York already has a gap between employer demand and the occupational and employability skills of the workforce. According to the National Skills Coalition, employer demand for middle-skill jobs in New York outstrips the supply of appropriately trained applicants by about 24 percent—in contrast to low-skilled jobs, for which there is an oversupply of applicants. In short, if the state commits to educating and training low-income New Yorkers for middle-skill jobs in an employer-responsive way, the jobs will be ready at the other end of the pipeline.

As a result of this looming labor shortage, New York’s employers have just as much to gain from new investments in education and training as its workers do. Their plight is likely to worsen over the next several years as the baby boomer generation reaches retirement age. In fact, the Department of Labor forecasts that more than 40,000 New Yorkers will leave their jobs each year in the decade ahead. The coming wave of retirement will have a disproportionate impact on several key sectors where most workers are older than the statewide average. In healthcare, manufacturing, and education, for example, more than one-quarter of the workforce is age 55 or older.7

The need for New York State to invest in workforce development has never been more urgent. As traditional sources of good jobs disappear—even amid an increasing shortage of workers in a variety of sectors—the opportunity to strengthen the state’s workforce system grows. However, to reach the largest number of New Yorkers with effective workforce programs, a portion of the state’s investment should be directed toward adult education and bridge programs. These programs can help prepare more of the state’s lowest-skilled workers to access educational and training opportunities and a path toward middle-skill careers. Taken together, new investments in education, training, and adult education can prepare many more New Yorkers for jobs in growing fields, while helping to ensure that the state’s economy has a healthy supply of trained workers in the decades ahead.

Increase resources for adult education—including literacy, math, and ESOL—as an onramp to the workforce

New York absolutely needs a major new investment in job training and workforce development programs. But with hundreds of thousands of adult New Yorkers most in need of basic literacy and language skills—and not just sector-specific training—Governor Cuomo and the State Legislature should devote a portion of the state’s new workforce investment to adult education.

Adult education programs form an essential piece of the workforce system by helping New Yorkers acquire the building blocks for success in today’s economy. They include literacy, math, and computer skills classes that prepare adults to earn a high school equivalency credential, as well as English for speakers of other languages (ESOL) programs that help immigrants gain proficiency.

It’s impossible to overstate the need for adult education programs in New York State. More than 2.1 million adults in the state lack a high school diploma or equivalent. Additionally, 2.3 million adults speak English “less than very well,” signaling a lack of English proficiency.8 These New Yorkers face serious barriers to career opportunities and advancement, and lack access to some of the most effective skills-building and job training programs, most of which require participants to have first demonstrated fluency in these basic skills.

Unfortunately, the state’s main funding source for adult education, the Employment Preparation Education (EPE) program, has not been increased since 1996. This is the case even though the number of adult New Yorkers with limited basic literacy skills—and the number of immigrants with limited English proficiency—has skyrocketed over the past two decades. In inflation-adjusted dollars, EPE funding has declined by 36 percent over the past two decades.

Federal adult education funding has likewise stagnated over the years, resulting in grants whose value erodes over time. Deterioration is not only visible in the number of adult learners served, but in the quality of their instruction. Where providers of adult basic education once hired full-time instructors with health benefits, offered professional development, and occasionally upgraded their computers and learning materials, such seemingly essential features have been cut back.

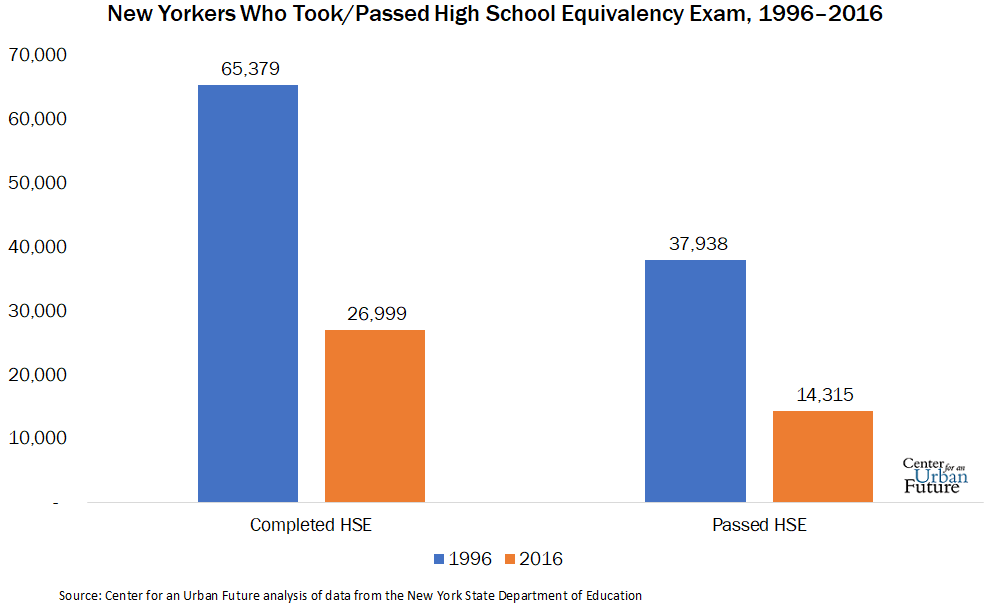

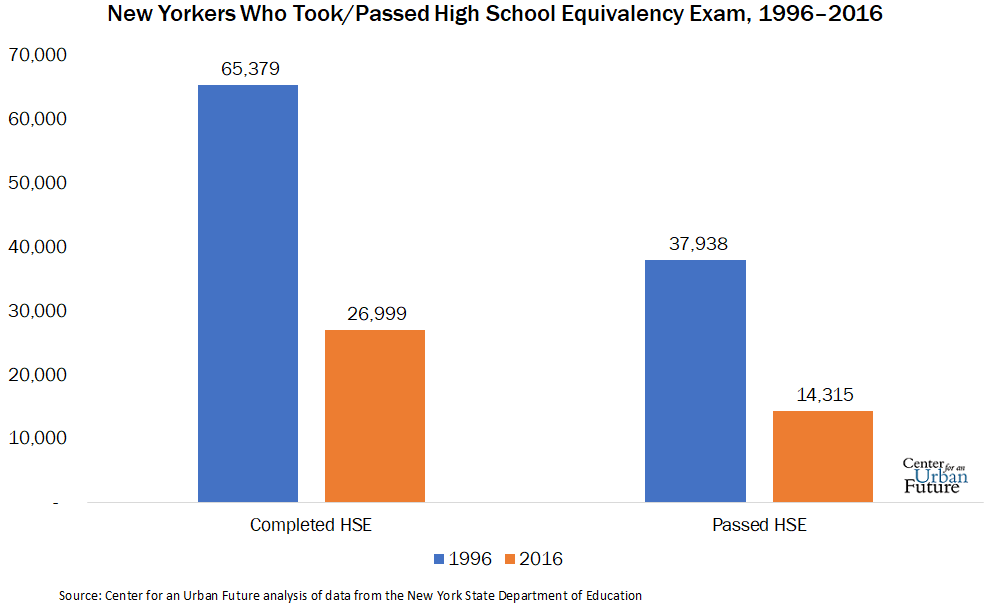

The impact can also be seen in the decline of high school equivalencies (formerly called GEDs), the primary gateway to good jobs for adults who did not graduate from high school. In 1996, 38,000 adults obtained a high school equivalency in New York. In 2016, only 14,000 did, a steep 62 percent decline over two decades. Between 2005 and 2013, the number of New Yorkers lacking English fluency grew by 14 percent, while the number of state-funded ESOL seats fell by 32 percent. Today, state-funded ESOL seats can accommodate only 1 in 39 residents who would benefit from ESOL instruction.

A major new investment in the state’s workforce development system presents a vital opportunity to reinvigorate adult education programs and connect them to further postsecondary education and career training. New York needs to reinvest in basic skills instruction to ensure that more New Yorkers are prepared to benefit from effective workforce training programs, while ensuring that adult education functions as a starting point for further skills-building—not the end of the line. New York should allocate a portion of the state’s new workforce investments to expand and improve adult literacy and math programs, computerize the state’s high school equivalency testing system, double the number of seats in ESOL programs, and scale up other adult education programs. The result would be a revitalized adult education system that can reach millions of underprepared New Yorkers and serve as an on-ramp to effective workforce development programs.

Ramp up bridge programs across the state

To ensure that low-income, working New Yorkers will benefit from the state’s new workforce investments, a portion of the plan should target the training needs of those who are hardest to serve. The first step is to include funding for adult basic education. But an emerging model can take this approach one step further, by preparing lower-skilled adults to transition into job training programs.

That is the idea behind bridge programs, which provide a crucial on-ramp to workforce training for the most skills-deficient workers. While precise definitions of bridge programs vary, a bridge approach typically includes basic skills instruction (often in math, literacy, or ESOL, and ideally taught in the context of an industry), while helping participants prepare for a job training or educational program.

Instead of treating adult education and career training as separate concepts, bridge integrates the two—a more practical approach for participants with serious barriers to employment, and one that allows them to build momentum toward a career. Optimally, the bridge model provides adult education in the context of an industry, leads to attainment of a credential such as a high school equivalency, and feeds into a training program that offers an industry-recognized certificate or other postsecondary credential. The training program might be a short-term occupational credential at a community college, a tech skills-building program run by a nonprofit, or a nurse’s aide training program at a local hospital—all of which can lead to higher wages and a stable career path.

Research has shown that bridge programs work for students with significant barriers to employment, including those with a reading level as low as the 7th grade. Still, our research finds that there are fewer than a dozen bridge programs in New York State. This is a missed opportunity in a state where 2.1 million adults lack a high school diploma and 2.3 million speak English less than very well.

New York boasts one of the most well-known and successful bridge programs in the nation: The Bridge to College and Careers program at LaGuardia Community College, which prepares students to pass their high school equivalency exams by teaching math and literacy coursework in the context of healthcare, science, or business.

Roughly half of LaGuardia’s bridge students are 26 or older; almost half are immigrants; and over 50 percent read at a 7th- or 8th-grade level. Many of these students have commitments that make going back to school complicated, such as multiple part-time jobs and children at home. Bridge offers them a clear sense of direction in their academic learning, and momentum toward postsecondary education and a career. A 2013 study by MDRC showed that students in LaGuardia’s bridge program were twice as likely as their peers to pass the equivalency exam, and three times as likely to pursue a postsecondary credential.

But LaGuardia is the only community college in the state that offers a robust program that includes education in an occupational context. With additional state support, there are clear opportunities to expand this model to other community colleges.

There are a few emerging programs that implement the bridge model upstate. CenterState CEO, a business development organization in Syracuse, has had success with a green construction training program that also teaches basic math and literacy. Other initiatives organized by community colleges, nonprofits, and intermediaries use elements of the full bridge model. The New York Association for Continuing and Community Education offers basic adult education that also bridges into a certified nurse’s assistant training program, and Monroe’s Middle Skills Bridge program prepares adults for an accelerated program in the college.

Nonprofit organizations are also committing to the bridge model, especially for young adults. In New York City, JobsFirstNYC's Young Adult Sectoral Employment Project (YASEP) takes a bridge approach to help connect 18-to-24-year-old jobseekers with employer-guided education and training. Per Scholas and The Door have collaborated on one such program, the five-week TechBridge, which helps young adults catch up on basic math and English skills before transitioning to Per Scholas’s free IT Support course. Per Scholas also offers a six-week CodeBridge program that feeds into a web development course at General Assembly, an adult education school.

Despite these strong examples, bridge programs in New York serve only a tiny fraction of the adult learners who would benefit from them. Other states have invested in bridge far more aggressively, recognizing the model as a proven strategy to increase economic opportunity. Washington’s pioneering Integrated Basic Education and Skills Training Program (I-BEST) quickly teaches students literacy, work, and college-readiness skills in one seamless arc, while Minnesota has incorporated the bridge model into its long-term campaign to connect adult basic education to community college opportunities. Governor Cuomo and the state legislature should make similar investments.

New York should expand its strongest bridge programs, while giving others the funding to add the contextualized education component to their programs. Investing in LaGuardia’s bridge program is an obvious first step, as well as piloting bridge programs modeled after LaGuardia’s in as many SUNY and CUNY colleges as possible. The state should also support the work of intermediaries like CenterState CEO that recognize potential for bridge programs, bring stakeholders together to create them, and connect bridge providers with populations that need adult basic education. In addition to directly funding providers of bridge programs and intermediaries, the state could play an organizing role by encouraging partnerships between schools, nonprofits, and employers to create bridge programs tailored to the needs of their communities.

Create accountability through better data

The need for new statewide investment in workforce development is urgent. But to ensure that this crucial investment is well spent, New York State needs to create a clearinghouse for workforce data--including cutting-edge sources of labor market data and statewide unemployment insurance data—that will help make workforce development and education programs more responsive to the needs of employers and more accountable to the outcomes of their participants.

To Governor Cuomo’s credit, his proposal would grow the state’s capacity to collect and analyze workforce data. But the plan should go one step further. By developing a secure central data clearinghouse as part of its workforce investment, New York can expand accountability throughout the workforce system and ensure that researchers and programs from across the state can access data on labor market trends and workforce outcomes.

An investment in better workforce data should begin with extending the capabilities developed at Rochester’s Monroe Community College (MCC) to every region of the state. MCC is unique among the state’s community colleges in that it has developed a sophisticated tool for analyzing labor supply and demand by sector and occupation. A student exploring a career in heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) maintenance, for example, can use the school’s online labor market index to discover that there are only 91 HVAC annual program completions in the Finger Lakes region, compared to 357 annual openings, making it a high-demand field. The entry-level hourly wage of $16 and the average wage of $24 are livable, if not exactly generous. This information is also valuable for workforce and college practitioners, as well as policymakers seeking to allocate scarce funding to programs that lead to in-demand jobs.

Scaling Monroe’s supply-and-demand data system statewide would be a huge step forward for New York State. But the new state Office of Workforce Development proposed by Governor Cuomo could provide an even more powerful planning tool by creating a system to evaluate the effectiveness of workforce programs. After all, identifying a skills gap is only the first step. Workforce and educational providers must then develop programs to prepare workers to fill that gap, and some programs will work better than others. In order to evaluate and improve state-funded programs, New York should establish a data warehouse that collects reliable workforce and educational data from multiple sources, integrates and analyzes that data, and then reports the most important information to key stakeholders.

What makes a data warehouse achievable is that New York already has much of the data it needs, albeit not in one place, and not accessible to end users. Instead, potentially valuable databases reside in various state and local agencies, where they remain siloed from one another. Where data is shared with organizations, schools or colleges, they often find it difficult to use without specialized knowhow and staffing.

An effective data warehouse enables users to track the progress of students through one or more programs and into the workforce. This capacity enables program leaders and policymakers to ask meaningful questions like “What difference did this program make to the participant’s educational or labor market outcomes?”

In Washington State, answers to that question drive every aspect of human capital development, informing decisions made by agency leaders, legislative committees, the governor, community colleges and workforce organizations. For example, Washington State’s data warehouse provided the basis for creating and scaling an entirely new service model, I-BEST, which combines basic skills and vocational instruction and has since become a national model.

And it’s not just Washington State. Students and program managers in Michigan, Florida, and Colorado can visit web-based clearinghouses to explore information on careers, long-term employment projections on specific occupations, needed skills and credentials, and the performance of programs that deliver them. In Mississippi, economic development officials used their data warehouse to prove to an international tire company that they could provide the skilled workers needed to staff a new plant. They got the plant, along with the 500 jobs that came with it.

Such research around program improvement and accountability happens in New York only at the local level, led by innovative practitioners like Monroe Community College and New York City’s Labor Market Information Service. Meanwhile, most state and local policymakers in New York are making decisions in the dark on how to fund education and workforce programs.

Pairing the supply-and-demand system proposed by Governor Cuomo with a sophisticated data warehouse will give a crucial leg up to policymakers and program managers from around the state who can find creative ways to build the skills of workers, improve programs, and meet the urgent needs of employers. New York should follow the lead of the many states that have already established this critical infrastructure and develop a data warehouse as part of a reinvigorated workforce development system.

Photo Credit: Clark Young /Unsplash

1. Analysis of 2017 Basic Monthly CPS data by Population Reference Bureau for the Working Poor Families Project.

2. Analysis of 2015 American Community Survey microdata by Population Reference Bureau for the Working Poor Families Project.

3. Melinda Mack, Madison Hubner, Lesley Hirsch, and Yuemeng Zhang, State of the Workforce: A Labor Market Snapshot for New York State, New York Association of Training and Employment Professionals, 2017.

4. Office of the Governor, “Governor Cuomo unveils19th proposal of 2018 State of the State: Strengthen workforce development to prepare New Yorkers for the jobs of the future,” January 2, 2018.

5. Anthony Carnevale, Jeff Strohl, and Neil Ridley, Good Jobs that Pay Without a BA, Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, 2017.

6. New York State Department of Labor. NYDOL projected employment from 2014 to 2024.

7. Mack, Hubner, et al.

8. Center for an Urban Future analysis of data from the 2012–2016 American Community Survey.