This is an excerpt. Click here to read the full report (PDF).

Every year, nearly 37,000 youth across New York State drop out of high school and join the 2.8 million New Yorkers who are already out of school and lack a high school diploma.In today’s highly competitive knowledge economy, where employers in almost every profession are demanding higher levels of educational attainment, these New Yorkers are falling further behind their more educated counterparts and increasingly being relegated to low-wage, dead-end jobs—if they can find work at all. For a very motivated and fortunate few, the GED offers a second chance at success. But for the vast majority of these people, a woefully inadequate system prevents them from attaining their GED and going on to college or career training.

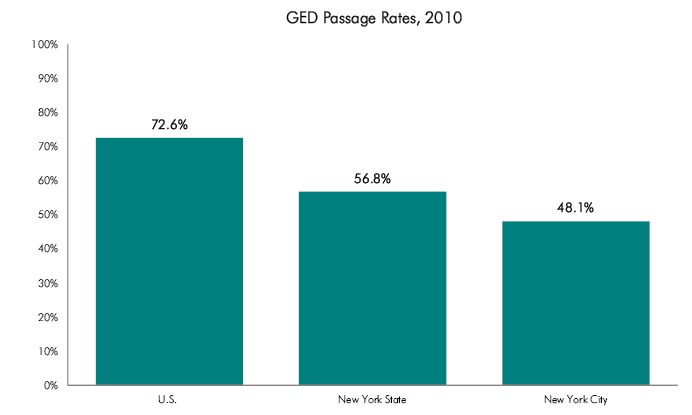

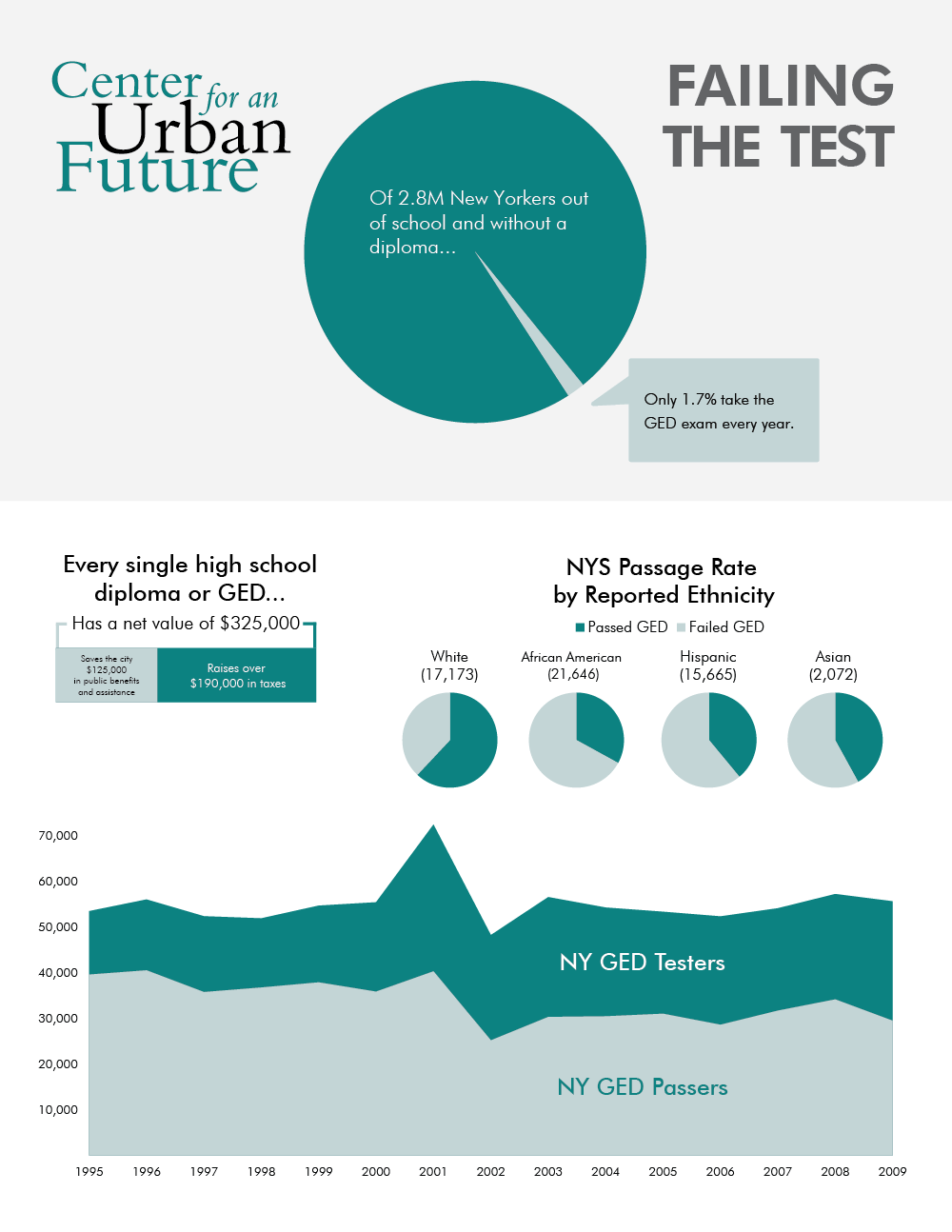

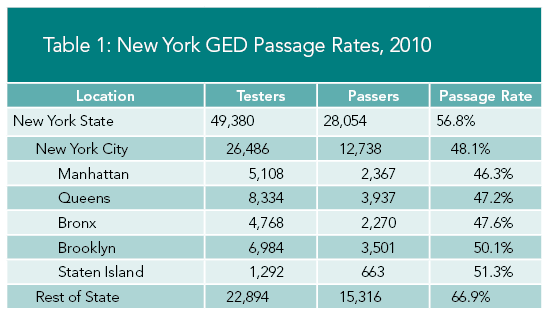

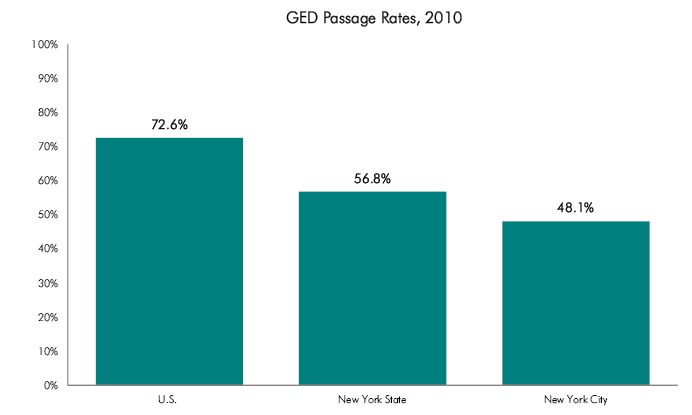

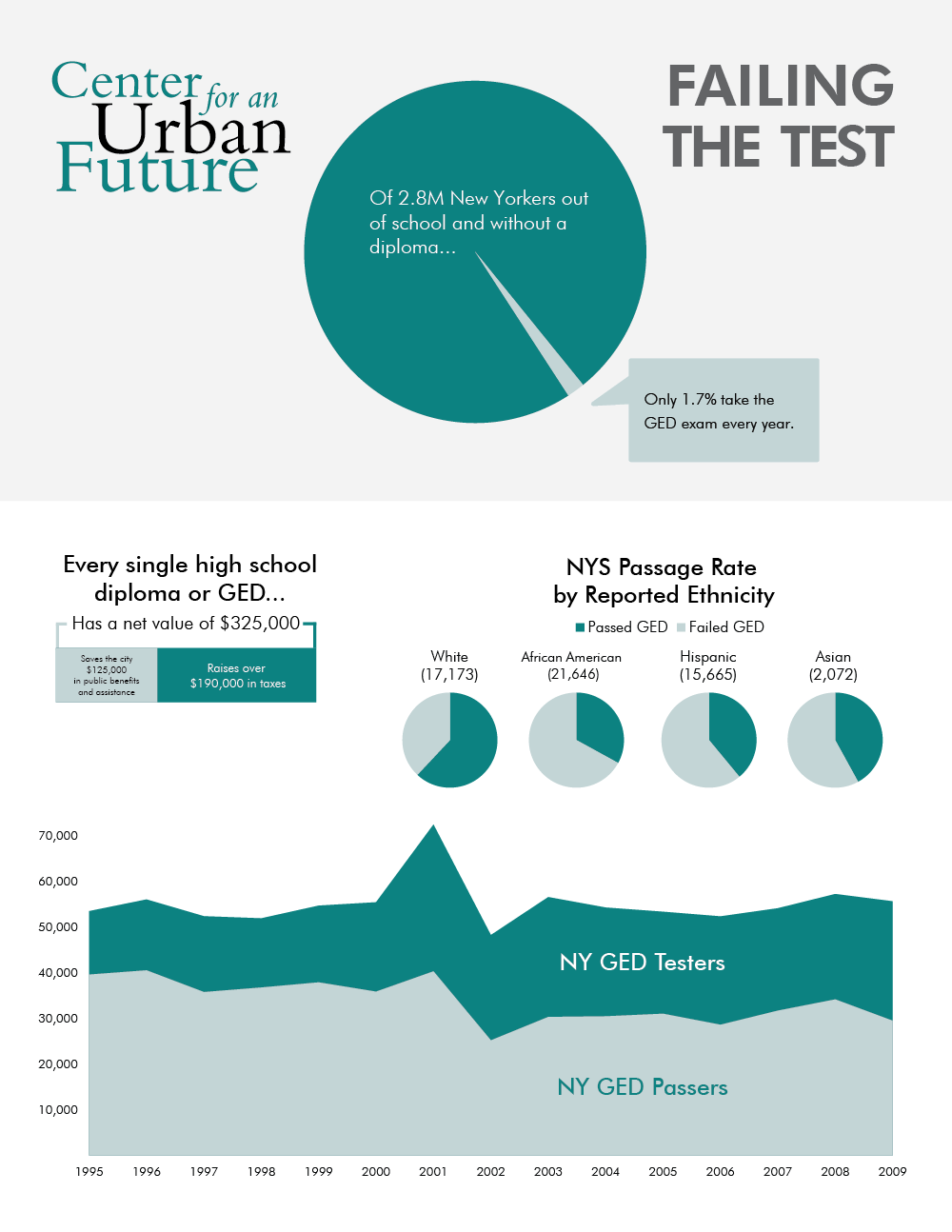

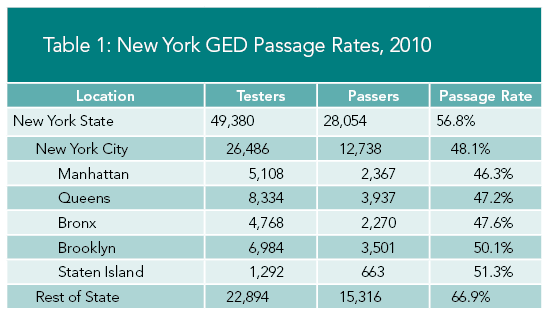

The GED system across the state and in New York City produces two related policy problems. First, not enough people are sitting for and passing the exam. And, second, very few of those who do pass the exam go on to postsecondary education or training. Of the more than 2.8 million people in New York State who are eligible to get their GED, only 1.7 percent takes the exam in a given year. And of those who do sit for the test, only 56.8 percent pass, making New York nationally ranked 49th out of 50 states in the country for GED attainment.

New York City fares even worse, with only 48 percent of people who take the GED exam passing it. Of those in the five boroughs who obtain their GED, only 11.6 percent go on to finish postsecondary career training or college.

Educators and policymakers on both the state and local levels have struggled to target the causes of these problematic outcomes and find creative solutions to address them. Resource constraints and a new GED exam planned for 2014 are now calling into question an already struggling system and are prompting calls for new policies and best practices. Our research suggests that there are meaningful changes that would produce systemic improvement, but they will require investment and collaboration among state and city officials and educators.

* * *

In this policy brief, we evaluate some of the policy and program recommendations that have been offered as models for improving the GED system. Our research was informed greatly by an array of insightful studies about the GED published in recent years, but we also gathered new data about GED policies and outcomes in other states and interviewed numerous state and local policymakers, program operators, advocates, and educators.

Our starting point is that New York’s poorly performing GED system is badly in need of reform. Doing so is not only vital for the thousands of New Yorkers who simply lack the skills and educational attainment needed to compete in today’s global economy, but it is critical to the future economic competitiveness of the city and state.

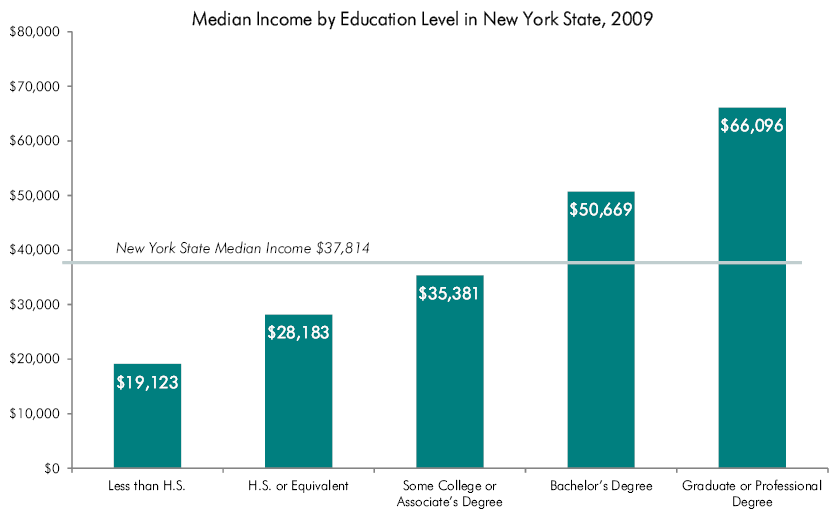

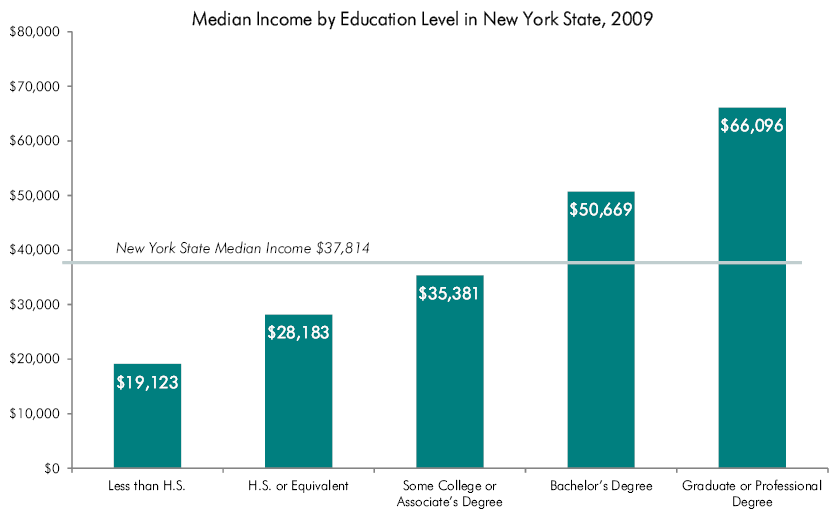

While the economy continues to struggle to rebound from the most recent recession, the forecast is even more dismal for those without a high school degree. The unemployment rate for high school dropouts is 14.3 percent, compared to 9.6 percent of those with a high school diploma and 4.3 percent of those with a bachelor’s degree or higher. Yet even for those who do find employment, their earnings fall short of what is needed to support themselves or a family. Dropouts earn an average of only $18,815 annually, a far cry from the average $31,735 it takes merely to be self-sufficient in New York City. “As a consequence of the recession, we are going to see a greater number of people who are ‘disconnected’. The chronic and perennial disconnection of young adults has not been effectively addressed” by the GED system or other programs, observes Lou Miceli, executive director of Jobs First NYC, a not-for-profit organization focused on reconnecting young adults to the economy.

The disparity in earnings between those without a high school diploma and other workers is growing. Whereas the income for workers without even a high school diploma has fallen two percent over the past few decades, earnings of high school graduates has increased by 13 percent. Meanwhile, income for workers with a bachelor’s degree has grown by 34 percent.

Although high school dropouts face enormous individual and financial challenges throughout their lifetimes, the issue is not theirs alone. There are also significant costs to the city and state as a result of such a poor performing GED system. According to the Community Service Society, a New York City based nonprofit that advocates on behalf of low-income New Yorkers and has authored studies about the GED, each person who does not complete high school or the GED costs the city $135,000 more than they pay in taxes over their lifetime. In contrast, those who finish high school pay over $190,000 more into the city treasury than is expended on their behalf. Thus, a high school degree or GED is worth $325,000 to the city.

With New York City having one of the highest concentrations of people lacking a diploma, the economic impact is staggering. There are approximately 1.6 million New Yorkers throughout the five boroughs who lack a high school diploma, more than half the statewide population of people lacking a diploma. This could amount to over $500 billion potential lifetime earnings lost after dropping out of high school. Fully 29 percent of the working age population in the city lacks a high school diploma, a clear and unsustainable failure of New York’s educational system.

All of this makes it clear that city and state officials need to focus more attention and resources on building up the skills of New York’s population so that more New Yorkers have the opportunity to obtain middle income jobs and more New York employers have access to the skilled employees they need. One good place to start is by repairing our failing GED system.