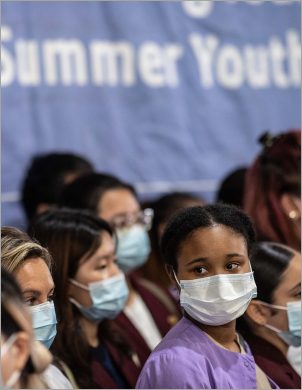

On a humid Friday morning last August, Mayor Eric Adams traded his customary suit for a cooking apron. In front of 250 delighted Summer Youth Employment Program (SYEP) participants at Gracie Mansion, New York City’s first vegan mayor mixed cucumbers, sweet potatoes, cabbage, onions, chickpeas, and spices into a salad. As he cooked, he talked: about his battle with diabetes and how he transformed his diet; about the intersection of history, culture, and food; about healthy eating and healthy living.1 When the mayor’s demo was complete, a diverse panel of young restaurateurs, celebrity chefs, and other culinary industry stars followed, engaging the teens in an hour-long discussion about jobs and careers in the field.

The event marked a high point in a memorable summer for SYEP: 100,000 young New Yorkers placed, thanks to a record $236 million investment from Mayor Adams and City Council. Yet, as the program reaches its 60th anniversary in 2023, SYEP could be doing much more to prepare the mostly low-income youth it serves for a labor market utterly transformed from when the program began. City leaders should take bold steps toward this goal by making SYEP more structured and standardized across providers, more connected to participants’ educational experiences and goals, and more intentional in readying youth for career success in high-demand sectors of the city’s economy.

***

SYEP runs for six weeks each summer, providing New York City residents ages 14 to 24 with up to 150 hours of paid work experience. Participants ages 16 and up earn the state minimum wage of $15 per hour. The NYC Department of Youth and Community Development (DYCD) administers the program through more than 60 contracted provider organizations. Each provider separately recruits participants and host employers. Most SYEP slots are filled through a series of lotteries, with the rest reserved for youth who meet specific criteria such as enrollment in designated schools or being in foster care, among others.

For decades, SYEP simply aimed to help keep participants out of trouble and provide them some additional money. It succeeded at these modest goals. A 2015 study of SYEP participants from 2005 to 2008 found that nearly a decade later, participants were significantly less likely to have died or been incarcerated than non-participants. But the experience had no measurable positive effect on their subsequent employment or earnings.2

DYCD has implemented a series of reforms to change that. In 2017, SYEP clarified its goal as “provid[ing] young people with experiences that prepare them for the workforce.”3 New program options are available, including the Ladders for Leaders competitive internship; Emerging Leaders, serving youth facing barriers such as foster care, homelessness, and justice system involvement; a separate track for 14 and 15 year olds, featuring career exploration and project-based learning; and CareerReady SYEP, a partnership with NYC Public Schools that reserves slots for designated high schools serving high-poverty communities to help align classroom learning with work experiences.

SYEP more than doubled in size under Mayor Bill de Blasio, who partnered with the City Council to increase city funding by over 600 percent during his mayoralty. Mayor Adams lifted the program to the next level in 2022, when he publicly committed to increasing SYEP from 75,000 to 100,000 jobs. To help achieve this dramatic expansion, DYCD added a small team to recruit larger employers. The city itself employed nearly 4,000 participants across 82 agencies and offices last summer, while exhorting private sector employers both to host participants and to offer site visits, panel discussions, and other activities to “turn the city into a classroom.”4

All these innovations clearly have made SYEP a richer and more valuable experience. At the same time, the world around the program has changed even faster than SYEP itself.

For all the good SYEP does, the program is not currently designed to help participants acquire the building blocks of career success, such as skills and credentials that employers value; a toolbox of personal attributes including resiliency, creativity, communication, and self-advocacy; and a strong support network. Nor does it connect enough participants to meaningful work experiences in the companies, occupations, and industries that drive NYC’s economy and are projected to grow over the next few years. This is particularly important considering the overwhelmingly Black and Brown population that SYEP serves—groups that remain strikingly underrepresented in fields such as technology, advertising and media, healthcare, and finance.

For example, the city’s healthcare and technology sectors accounted for just 5 percent and 1.6 percent of SYEP worksites respectively in 2022. The media and entertainment industries together comprised just 1.7 percent of all sites. Business and financial services together accounted for just 1.3 percent. Instead, placements were concentrated in low-paying industries like daycare providers and day camps (15.3 percent), social services (7.5 percent), and retail (8.4 percent)—the latter of which is projected to lose more than 10 percent of its jobs by 2028.5

Ideally, providers could utilize work settings like retail or daycare to help younger or less experienced participants build foundational skills, before advancing in subsequent years to more challenging placements in higher-demand fields. But two structural factors render this impossible. First, most participants enroll through a lottery system, meaning that providers might not know who they are serving until late spring, when it is often too late to fully assess participants’ needs and interests. Second, SYEP’s decentralization—with each provider responsible for recruiting its own host employers, with limited access to the small pool of centrally recruited partners—means that placement options for youth might be limited to the nonprofits and retail sites those providers already know. For now, these elements combine to dampen the long-term value of SYEP experiences.

***

As they learn and grow, young people move beyond what’s familiar, comfortable, and limiting, to mature into the best versions of themselves. Programs must similarly evolve. Mayor Adams and City Council have proven their commitment to SYEP through funding and championing the program. To make SYEP the best version of itself—a powerful engine of career readiness—they should adjust the program in alignment with three key principles:

- Emphasize durable skills and holistic development through an explicit sequential model. Young people hone skills in academic disciplines like English and math over a period of years, not weeks. SYEP should reflect that approach by defining clear goals for each program experience toward helping youth build workplace skills over multiple years—from self-regulation and workplace communication for younger participants, to sector-specific competencies for those closer to the labor market.

- Rationalize employer engagement and other SYEP functions. Making every provider responsible for every aspect of SYEP represents a missed opportunity to leverage providers’ respective strengths and create efficiencies that could free up money for programming. DYCD could restructure the current approach by consolidating contracts to engage networks of providers on a community or borough level, further centralizing employer engagement to generate additional placement opportunities shared by a common pool, or other possibilities for expanded place- and sector-based approaches.

- Make SYEP universal. Programs like CareerReady Work Learn & Grow, a partnership between DYCD and NYC Public Schools that offers a year-round complement to SYEP serving 3,000 high school students, implicitly recognize that all youth need early work experience and skill development to be on track for career success. New York City should embrace this reality with an explicit commitment to making career-connected learning and access to paid work experiences, including SYEP, available for all. This move would enable stronger year-over-year planning, provide structure and resources to fully integrate career readiness into education and youth development, and powerfully demonstrate the city’s determination to give every resident a strong shot at a life of choice and purpose.

David Jason Fischer is principal of Altior Policy Solutions, a public policy consultancy. From 2015 to 2022, he served as executive director of the NYC Mayor’s Office of Youth Employment.

Endnotes

1 “Mayor Eric Adams Hosts Summer Youth Employment Program Student Cooking Demonstration,” August 5, 2022; online at https://www.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/577-22/transcript-friday-august-5-2022-mayor-eric-adams-hosts-summer-youth-employment-program

2 Alexander Gelber, Adam Isen, Judd B. Kessler, “The Effects of Youth Employment: Evidence from New York City Lotteries,” 2015; online at https://gspp.berkeley.edu/assets/uploads/research/pdf/gelber_isen_kessler_051915.pdf

3 Youth Employment Task Force Report, 2017; online at https://www.heretohere.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Youth-Employment-Taskforce-Report.pdf

4 Summer Youth Employment Program, 2022 Annual Report: online at https://www.nyc.gov/assets/dycd/downloads/pdf/2022SYEPAnnualReport.pdf

5 Center for an Urban Future analysis of 2022 SYEP worksite data provided to CUF by DYCD. Employment projections from the New York State Department of Labor.