New York City’s Summer Youth Employment Program (SYEP) is, in many ways, bigger and better than ever. Thanks to record investments from Mayor Adams and the City Council, the program—which launched last week—will connect more than 100,000 young New Yorkers with paid work opportunities, more than double the number a decade ago. In addition, SYEP has strengthened its ties with the public schools over the years and added a host of innovative options, from the Ladders for Leaders competitive internship to CareerReady SYEP, a partnership with NYC Public Schools that aligns classroom learning with sector-specific internship placements.

Overall, SYEP has been a resounding success. But in one critical area the program has fallen short—namely, connecting young people to career opportunities in the highest-paying, fastest-growing companies that are shaping the city’s economic future.

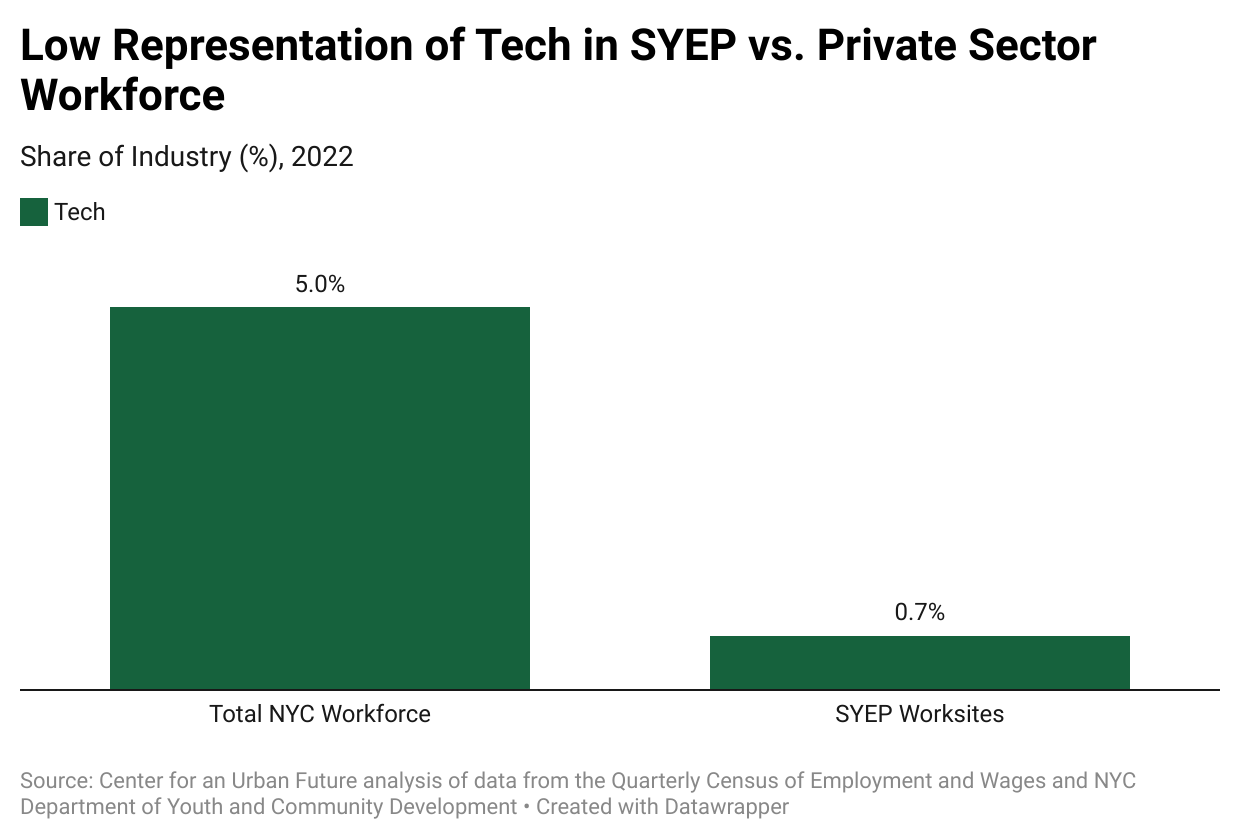

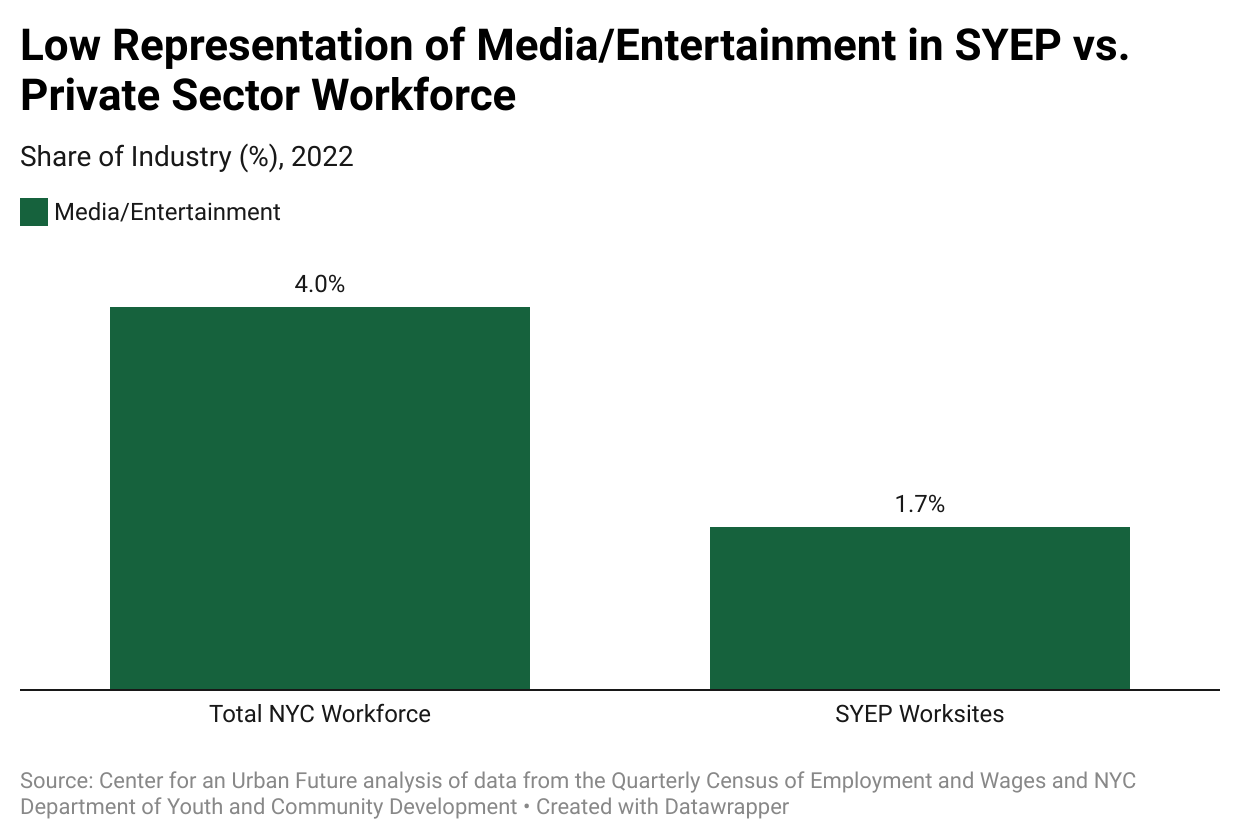

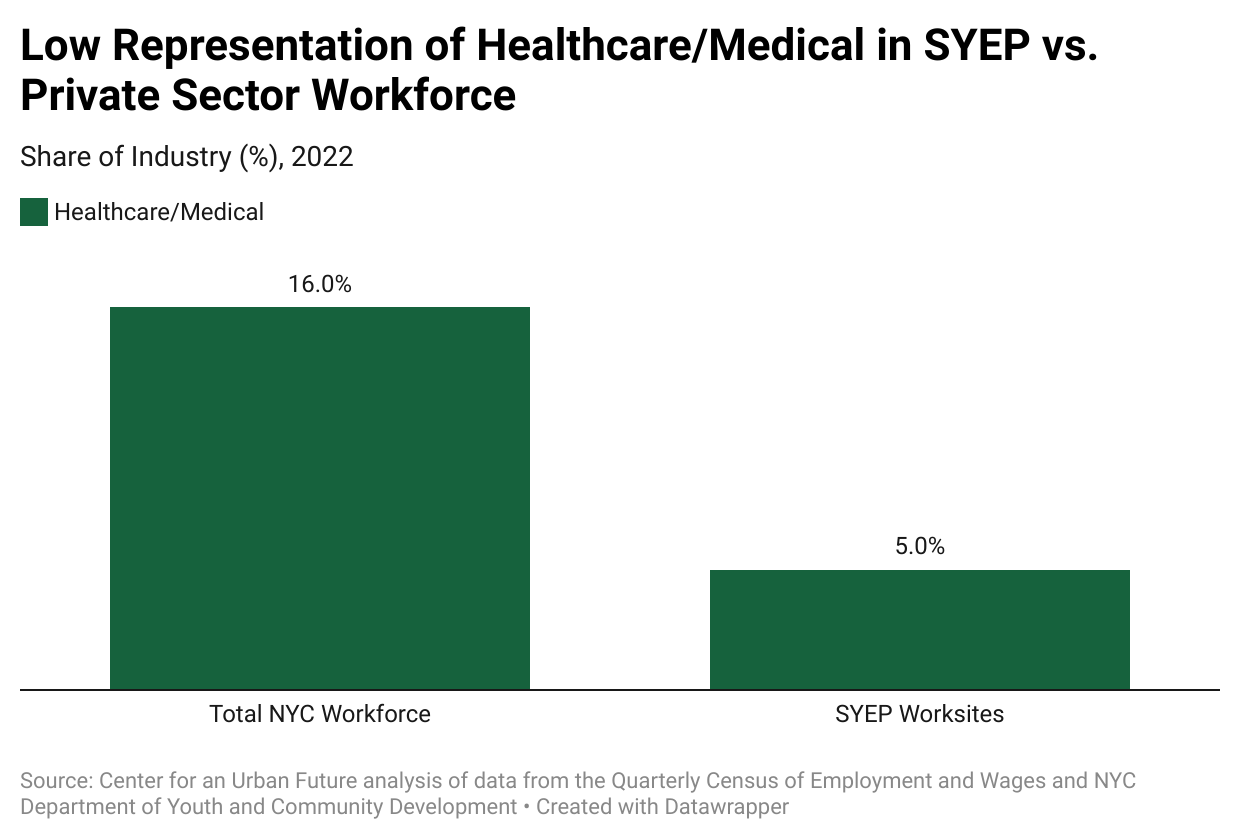

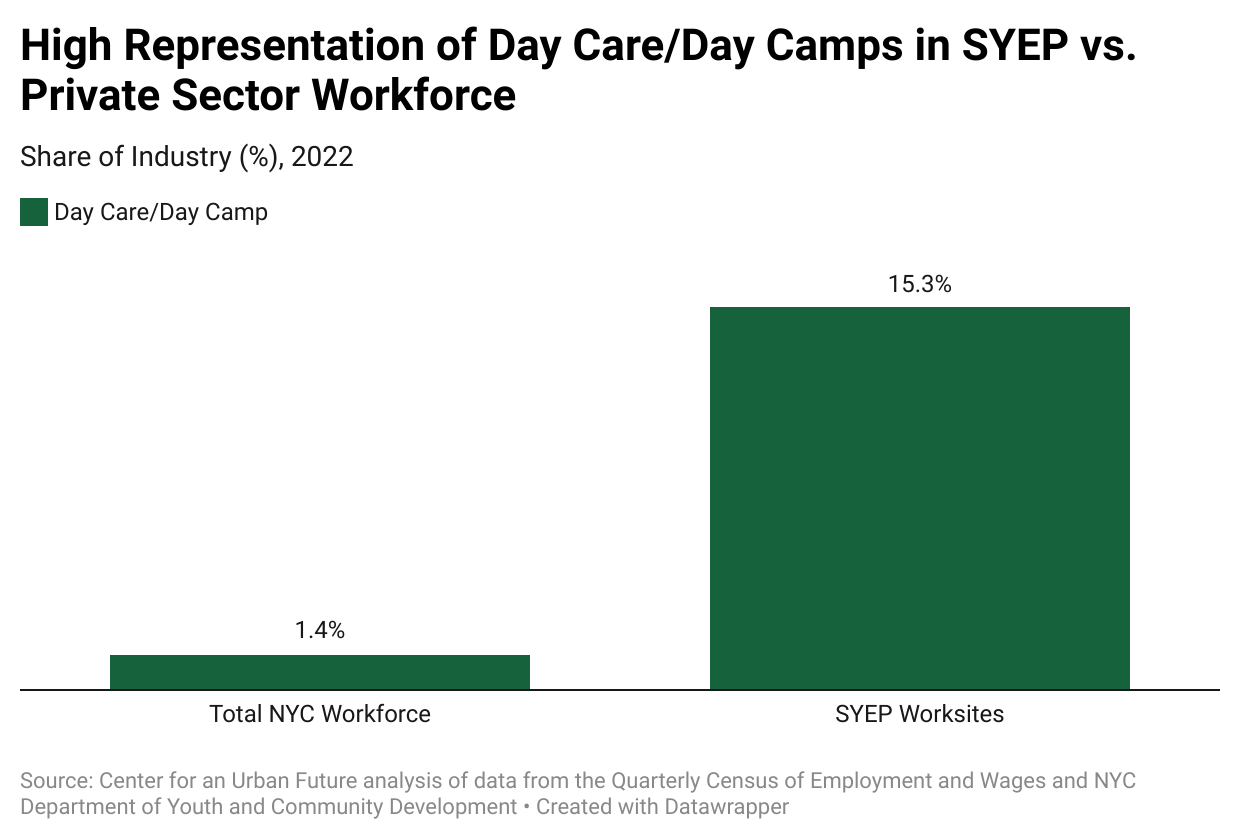

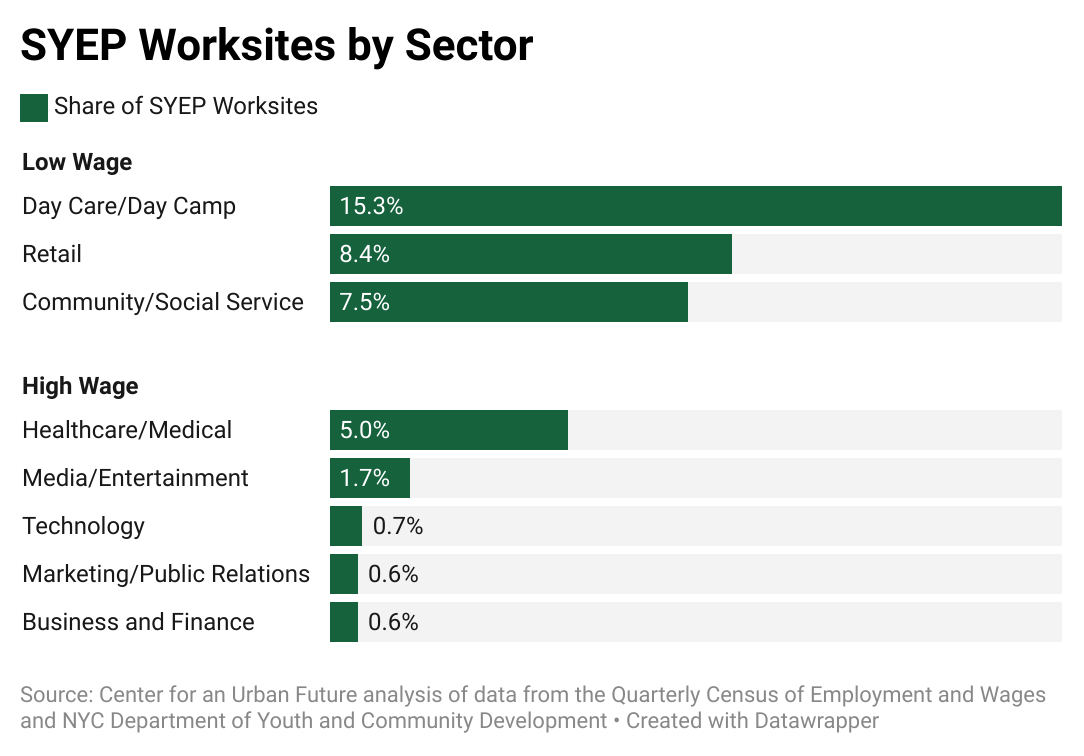

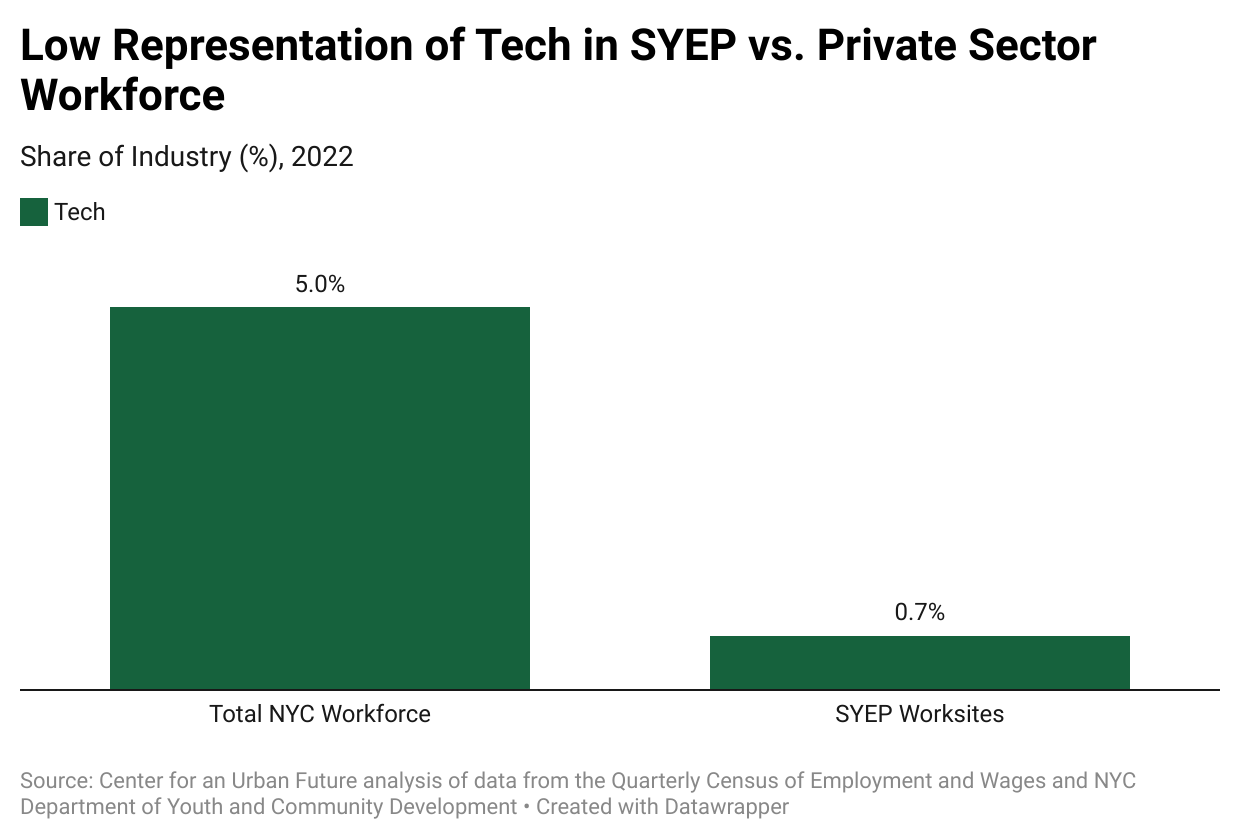

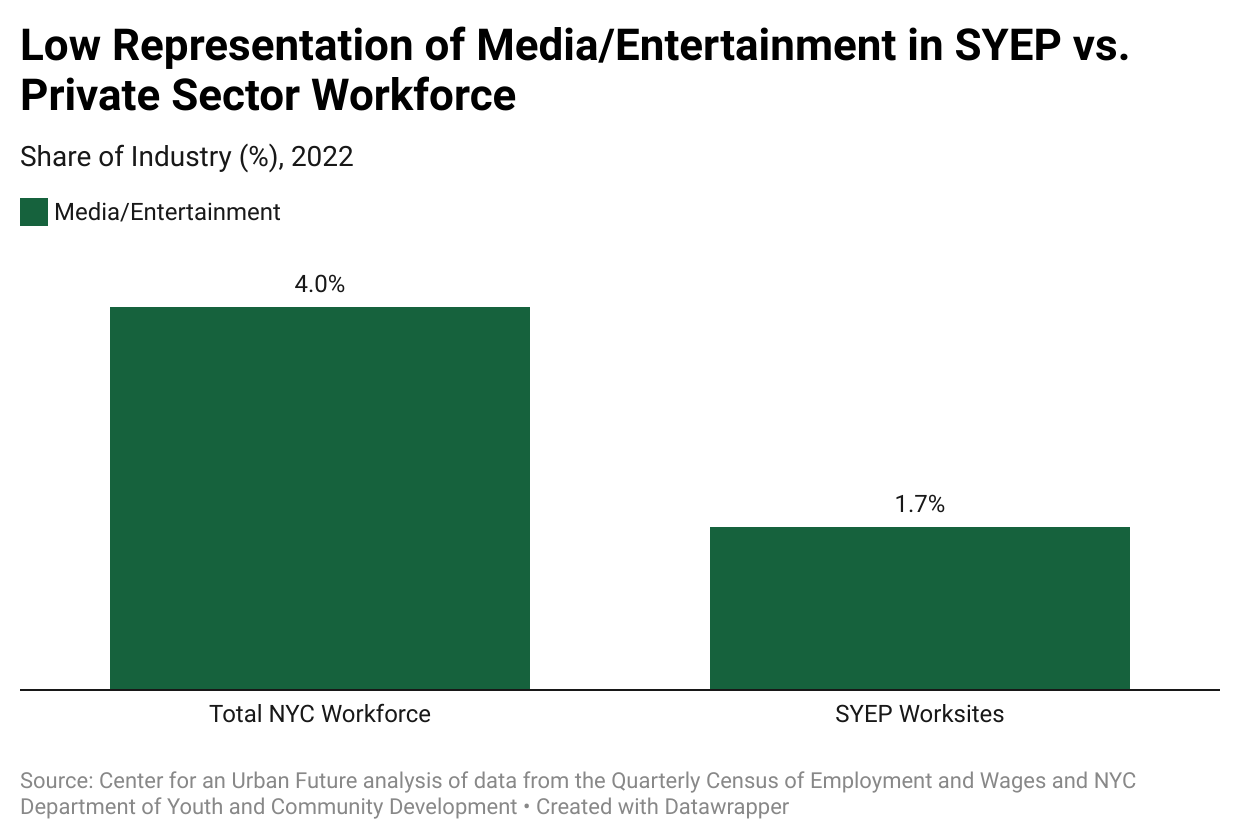

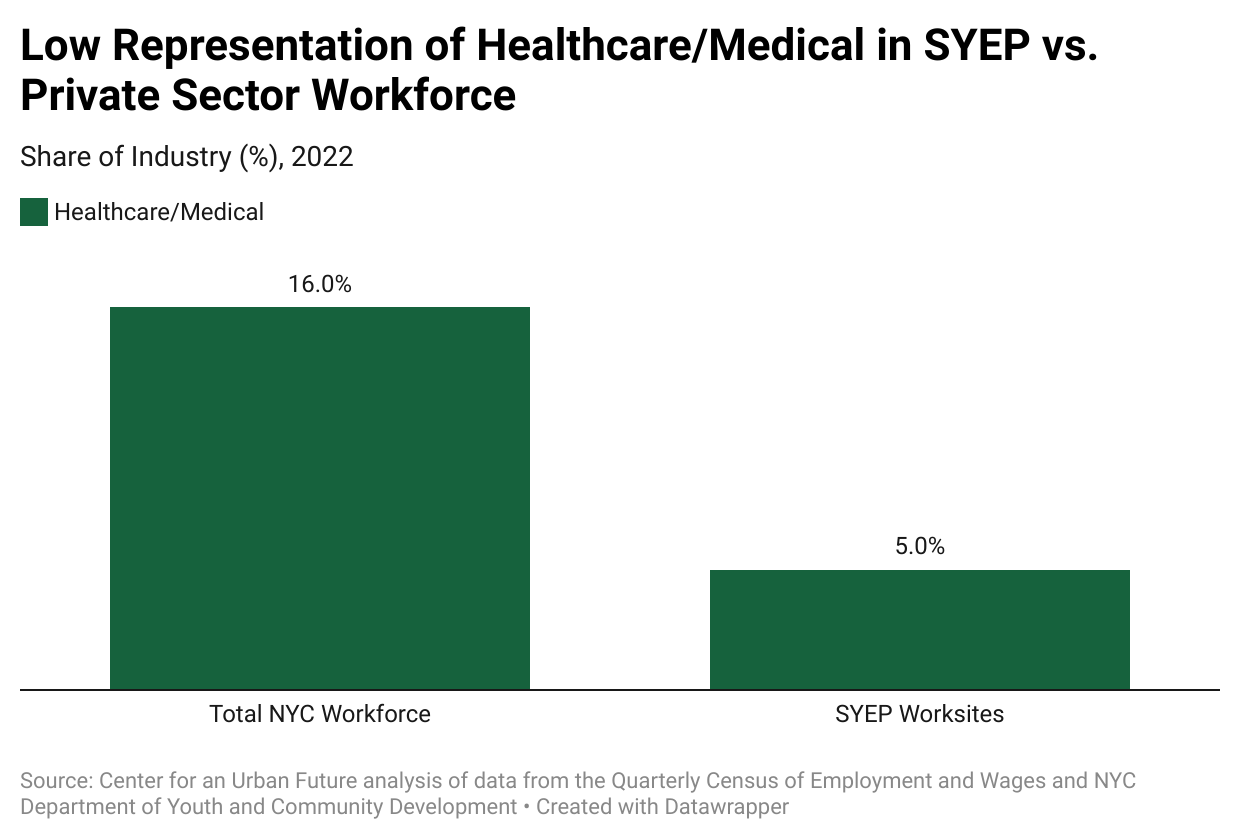

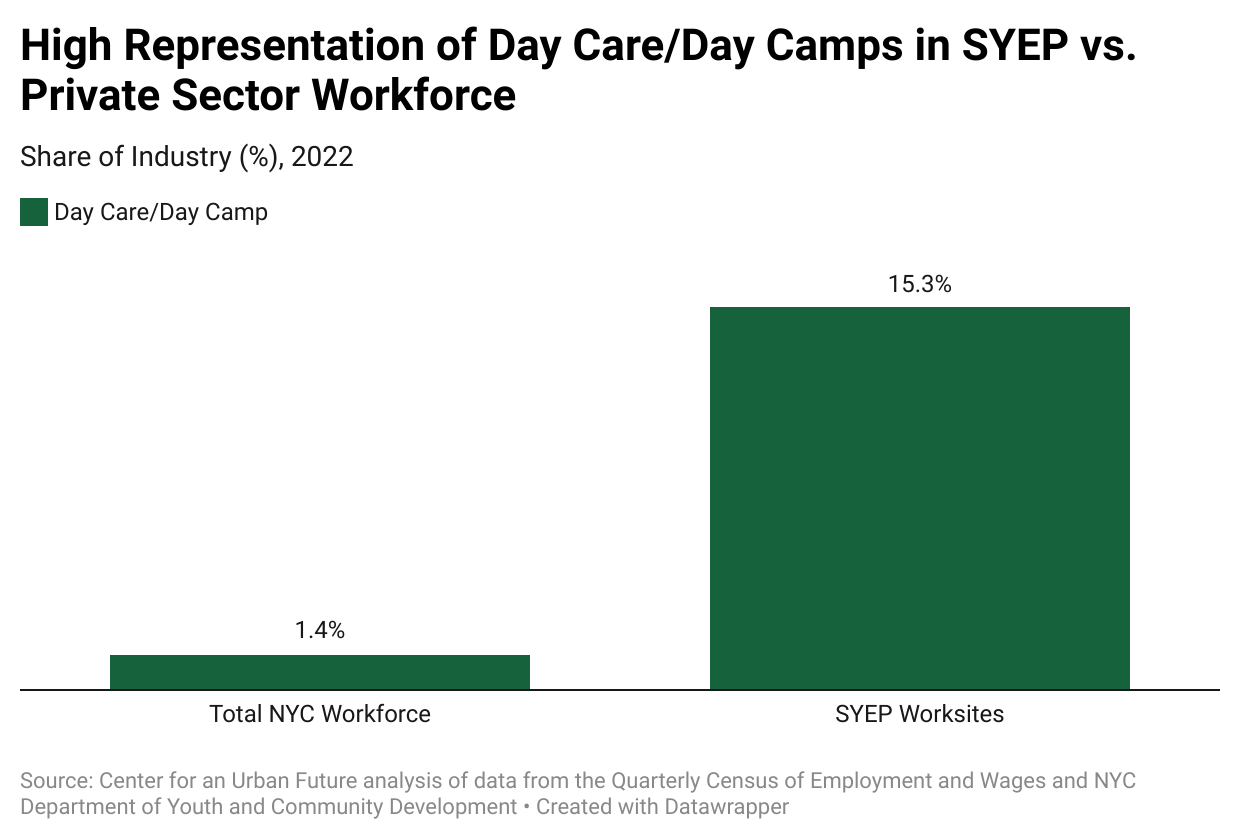

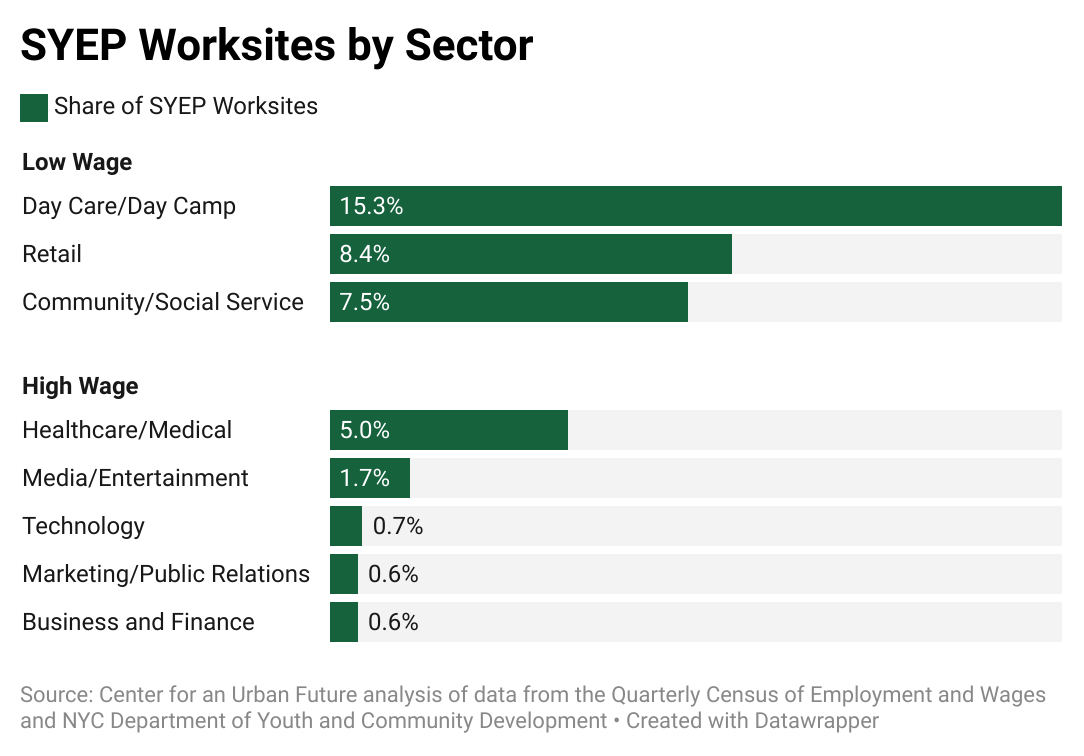

As of 2022, just 0.6 percent of SYEP worksites were with companies in the business and finance industry, only 0.7 of SYEP were with tech employers, 1.7 percent were in media and entertainment companies, and 5 percent were in the healthcare sector. Placements have instead been concentrated in lower-paying industries like daycare providers and day camps (15.3 percent), social services (7.5 percent), and retail (8.4 percent).1 Retail alone has lost 13.2 percent of jobs since 2015, and is projected to sustain further losses in the years ahead.2 And while day camps and social services organizations can all provide young people with valuable work experience, they are overrepresented in today’s SYEP.

“We're lacking the opportunity to light a spark with young people without the full access to the plethora of careers and industries available,” says Jessica Bynoe, president of PENCIL, a nonprofit connecting schools to industry, and an SYEP provider through its more career-focused Ladders for Leaders initiative. “If we're not really making sure they understand that there's multiple pathways, there's multiple types of jobs they never knew existed, how can we ever really create equitable access to that potential future?”

The near absence of high-growth and high-wage employers in the city’s largest youth employment program poses a significant challenge. At present, Black or Hispanic New Yorkers remain strikingly underrepresented in well-paying sectors such as tech and the creative economy. Black New Yorkers hold just 9 percent of jobs in film and TV, and 8 percent in advertising; Black and Hispanic New Yorkers make up 43 percent of the city’s overall workforce, but account for just 20.8 percent of tech sector employment.3 Closing these gaps will require new efforts to ensure that young people from diverse backgrounds are able to explore opportunities in these industries and build career-connected skills.

In particular, youth workforce development experts say that New York City’s young people need exposure to professionals who look like them to be able to imagine the full range of potential careers.

And as much value as there is for youth, SYEP providers add, there’s also a significant but often underrealized value proposition for employers, too, who gain the opportunity to shape their future workforce while benefiting from the fresh perspectives that young people provide.

“Employers feel these young people bring a lot of ideas and a lot of energy,” says Natalie Martinez, the director of workforce development at HANAC, a Queens social services nonprofit and long-time SYEP provider. “They love the innovation of young people, the new ideas.”

This report finds several points of frustration with the program’s operation, management, and bureaucracy that prevent more private sector employers from getting involved. Most importantly, the program’s short duration—six weeks—is a challenge for many employers. It gives them very little time to onboard young people with little or no work experience and to structure an internship that is valuable for both the business and the participant. Employers also cite confusion over how to connect with the program, frustration with fielding in-bound requests from multiple providers, and challenges with an internship model and schedule that many find rigid and rushed.

Other obstacles include: the limited resources to support employers during the process; too little support for industry-specific training to prepare interns to succeed; and the nature of SYEP’s lottery system, which limits the ability of young people to connect with employers that are aligned with their career interests. As a result, it is not only difficult to bring employers on board but also to retain them. For example, in 2020, approximately 100 companies from the tech sector participated; this year, according to Tech:NYC, the number has fallen to fewer than ten.

“I think tech employers want to plug in, but there's a lot of bureaucracy that exists around opting into the program,” says Sarah Brown, chief of staff at Tech:NYC, the industry association for the city’s tech sector.

Over the past two years, Mayor Adams and the City Council have reaffirmed their commitment to SYEP, boosting the number of seats, funding free MetroCards for participants, and allocating resources to develop a small, in-house employer engagement team at the Department of Youth and Community Development (DYCD), among other steps. But much more should be done to address the barriers that have historically prevented more private sector employers from participating in the program. As the city prepares to release a new SYEP request for proposals to providers in 2024, the months ahead present a major opportunity to rethink aspects of the program that are not working for employers and to create new mechanisms to strengthen employer partnerships. By bringing more employers from the city’s well-paying growth industries into the program, city leaders can ensure that New York’s flagship youth employment initiative evolves to become a more powerful engine of economic mobility.

Key Challenges for Recruiting More Employers Into SYEP

1. Entry points for employers into SYEP are decentralized and confusing.

Employers who want to partner with SYEP must navigate a decentralized marketplace of access points. Individual nonprofit providers are largely responsible for administering the SYEP program and for recruiting employers, although DYCD also seeks out employers directly and through city agency partners. But each entity is working individually to secure these partnerships. That means, SYEP affiliates say, that multiple providers may be trying to establish a partnership with a single employer, often leaving potential employer partners confused about where and how to tap in.

“If you think about a big company, let's say Walgreens, there are like 10 providers who are working with Walgreens in separate ways. And they are all competing for these same jobs,” says Monia Salam, program director of work-based learning at ExpandED Schools, an education-based nonprofit and SYEP provider. “And there might be employers who are like, ‘Well, right now I'm trying to run my organization and I don't want to get caught into one of these webs.”

DYCD has its own in-house employer engagement team, which has worked to boost SYEP’s employer relationships, but it has just four team members. While the agency has taken steps to support nonprofit providers to conduct employer outreach, there is almost no infrastructure in place to coordinate engagement. This has led to a competitive rather than collaborative mindset, with provider organizations vying for relationships or, in some cases, fearing that DYCD will take over their existing relationships.

In addition, efforts remain largely disconnected and uncoordinated among the city’s business-facing intermediaries, such as chambers of commerce and trade associations, entities with existing employer relationships like the city’s career and technical education (CTE) high schools, and other agencies with employer connections—from the New York City Economic Development Corporation to the Department of Small Business Services. Duplicative outreach from these intermediaries and agencies often sours some businesses on the opportunity to participate, while other employers are never contacted at all.

2. Too many employers from growth industries are left on their own to navigate SYEP.

The vast majority of SYEP worksites are coordinated by nonprofit organizations across the five boroughs. While these community-based organizations are often excellent at providing a range of supports for the young people participating in SYEP, most have extremely limited experience building relationships with private sector employers. According to industry leaders interviewed for this report, employers are given little assistance in navigating the many requirements of the program. This includes applying to host interns and developing a structure for the program, coaching staff on intern supervision, and aligning educational and business objectives. Fortunately, there are subsets of SYEP that operate differently from the main program’s lottery model in ways that successfully engage potential SYEP employer partners in growing and well-paying industries. The problem is that these components of the system make up a small share of total placements.

One segment of SYEP that is succeeding in developing more effective relationships with employers is SYEP CareerReady, in which nonprofits work with New York City public schools to co-create an SYEP program to reflect the career interests of their schools and students. For example, the nonprofit DreamYard, which connects students to pathways in the creative economy, works with three schools in the Bronx to give students SYEP opportunities in that high-opportunity sector. As a sector-based organization with strong connections to the industry, DreamYard recruits creative companies, communicates expectations to employers, and works with them on a robust framework of work-based learning opportunities. It also preps youth with the background knowledge needed to navigate a creative sector workplace—an important support that helps ease employer hesitation to bring on teens who may not have prior experience while setting interns up for success.

DreamYard’s co-executive director Tim Lord says industry-focused intermediaries like his can streamline the SYEP experience. “[Organizations like ours] have the mission alignment to create internship opportunities and relationships with employers aligned with the work that we do,” says Lord. “It’s sector based, it's interest based, it's mission based. It's a different kind of level of commitment to building out the employer partnerships.”

CareerReady SYEP has grown considerably, serving about 21,000 SYEP participants last year, up from 12,000 in 2021. Experts on employer partnerships say while the general SYEP lottery may help to facilitate short-term access to a program with more demand than available seats, options such as the schools-based CareerReady should be expanded significantly to bring more employers from growing industries into the fold.

“The only time that I recommend employers get involved with SYEP is if it's through a program with a strong intermediary,” says Merrill Pond, executive vice president of the Partnership for New York City, a nonprofit membership organization comprised of more than 300 leading employers. “I think the benefit of having an intermediary is that the high school student is not dropped at your door and you’re told to figure out how to develop a meaningful opportunity. Instead, the intermediary works with the employer every step of the way.”

Another subset of SYEP also has a higher volume of high-wage and fast-growing employers than does the traditional lottery system: Ladders for Leaders. Some notable employer partners include Bloomberg, A+E Networks, and LinkedIn. Instead of relying on the lottery, these intermediary-run programs develop more substantial job descriptions for each internship, focus more intensively on youth training, and match youth more readily with employers that reflect their career interests. But the program is selective—reserved only for students with at least a 3.0 grade point average and previous work or volunteer experience. The program also has very limited spots.

“Ladders [for Leaders] under the umbrella of SYEP really only represents about 2 percent of the slots that are available,” says Bynoe of PENCIL, one of three Ladders for Leaders providers this year.

A Ladders for Leaders internship training workshop. Photo credit to PENCIL.

A Ladders for Leaders internship training workshop. Photo credit to PENCIL.

3. The rigid internship model poses particular challenges for employers in the tech sector.

In 2020, SYEP operated as Summer Bridge, a virtual program where employers largely gave groups of interns a project-based “workplace challenge” to solve for their company. This highly flexible model—along with a major recruiting push from Tech:NYC—brought in scores of tech employers. But once the flexible structure of Summer Bridge dissolved after that year, dozens of tech partners left the SYEP program.

Tech employers and intermediaries say that the flexibility built into Summer Bridge was critical for making SYEP work for their industry. Under the project-based framework, teens helped Brooklyn-based Etsy improve its user experience, and recommended TikTok strategies to a tech firm’s marketing team. One group of young people worked with the professional social network LinkedIn to suggest how the career site could market itself better to young people. The workplace challenge, several SYEP affiliates say, was a highly successful model that allowed employers from growing and high-wage industries to tap into the program for the first time.

“The interesting thing about the workplace challenge was that employers were thinking of this mostly, when they engaged, as a way to give back,” says J.T. Falcone, deputy director of policy and advocacy at United Neighborhood Houses, an organization that represents the city’s 46 settlement houses and includes many SYEP providers. “But what they were surprised to learn, particularly in tech, was that it was actually super valuable because you’re getting a focus group of consultants within, in many instances, your target age range or an age range that you’re missing to ask very direct questions of. And do it in a collaborative environment.”

However, after 2020, SYEP providers and employers say the program scaled back the project-based model, reserving it exclusively for 14- and 15-year-old participants. Tech:NYC reports its SYEP partnerships with employers dropped dramatically from 100 to about five, largely due to this lack of flexibility.

A highly successful component of Summer Bridge for tech employers, alongside the project-based “workplace challenge,” was that it was virtual. Since 2020, SYEP has been somewhat flexible on whether internships are in-person, hybrid, or remote, but most internships remain entirely in-person; in 2022, 75.3 percent of worksites were in-person, 15.7 percent were virtual, and 8.8 percent were hybrid. And even while SYEP has allowed for more flexibility on remote work, industry leaders interviewed for this report say that many are under the impression that SYEP administrators strongly prefer in-person worksites where companies oversee participants in the office for up to 25 hours per week. For companies that are themselves operating with a significant share of remote or hybrid workers, providing hands-on, in-person management of high school interns has been a very challenging guideline to adopt. The Summer Bridge program also offered support to companies in supervising interns, a great boon to tech employers in particular.

“SYEP should think of reducing the number of hours of employer oversight,” says Sarah Brown of Tech:NYC. “That’s a barrier to entry—and it's a non-starter for many small- to medium-sized tech companies.”

The only hybrid, project-based models Tech:NYC’s employer partners facilitate within SYEP are with 14- and 15-year-old participants. Many SYEP affiliates and experts on developing employer partnerships say a project-based model similar to the 2020 workplace challenge–for all ages, not just the younger groups—could bring more high-wage and fast-growing employers to SYEP.

“When it [SYEP] switched to workplace challenges during the pandemic, it was all online. Several employers who were not previously engaged with SYEP got involved,” says Merrill Pond of the Partnership for New York City. “They saw it as a good opportunity to participate in the program.”

An expansion of the project-based program model would require better alignment between the city and New York State. According to providers, that’s because the state declined to reimburse the city for the subsidies granted to participants in the workplace challenge model because those placements weren’t classified as work in the same way that traditional internships are. Industry leaders and providers alike say that the city and state should be able to meet in the middle, enabling the workplace challenge model to qualify as “work” so that it can be opened back up to older participants and made widely available in industries like tech where the model is seen as particularly effective.

“The city wasn't able to recoup the state funding for 2020 because the state looked at that and said, ‘that's not work,’” says Falcone. “And so, as a result, DYCD has avoided re-implementing the workplace challenge in any kind of new version.”

4. Employers need help to design and implement SYEP internships—especially to meet industry-specific needs.

Another core obstacle to employer engagement and retention is the chronic lack of support for employers who are interested in the program but unsure how to make it work. SYEP providers and employers say that employers are given minimal training or guidance on how to design and implement the program, and there are few opportunities for employers in the same sector to learn from each other and create industry-specific iterations.

In recognition of this problem, DYCD’s small employer-engagement team has begun to develop some resources, creating an internship design kit last year and a short YouTube playlist for employers, but, as one provider says, employer training and support is still in its “nascent stages.” Nonprofit intermediaries and providers like PENCIL, Futures and Options, and several others have created effective and robust guidance for employer partners, but additional resources will be needed to expand those models across the entire SYEP ecosystem.

JobsFirstNYC, a nonprofit that focused on expanding economic opportunity for young adults, has convened government, nonprofit providers, and SYEP employer partners, to examine how to better build and sustain SYEP employer partnerships, especially among smaller businesses. It identified a significant need for expanded employer guidance and technical assistance, in particular “greater onboarding support for employers, including how to work with young adults.”4

SYEP affiliates describe different levels of training across the program, with some employers getting training while others receive virtually none. All providers are required to hold an orientation with their participating worksites, but the resources vary significantly from provider to provider. Complicating matters even more, that support is offered not long before the first interns arrive—and only once an employer has already agreed to participate.

“There are no resources for employers,” says Monia Salam of ExpandED Schools. “When you are a worksite or SYEP provider, you do one training where you learn about how to input or approve students’ time.” Salam and other providers suggest more is needed to train employers on everything from how to work with young people and how to create appropriate job descriptions to how to provide advice on career mentoring.

The lack of resources for employers is compounded by the limited training available to youth themselves before entering the program. While that might not be an issue for work sites such as day camps, it’s a particular problem for employers in growth industries where advance preparation can help ensure that interns are set up for success. Many SYEP providers and employers described the need for more industry-specific training that would give SYEP participants a foundation of knowledge and context before entering into a professional workplace.

“If someone had no experience in this space, and not having any training and support for supervisors, that's a tall order,” says Tara Bellevue, vice president of inclusion, diversity, equity, and access strategy at NAF, a nonprofit that helps students prepare for college and careers, and an SYEP affiliate. “[Employers] end up not being sure about what to do with the student because you're not sure of the student's level of expertise or content knowledge” and there are few resources available to help.

5. The short-term, standalone nature of SYEP is not aligned with the needs of many high-growth employers.

SYEP takes place over six weeks, starting in July, with placements made through a lottery system. Employers may not be notified of who they are receiving until late June. The result is a scramble to set up the supervision and structure needed to carry out a program that includes some interns with prior interest in the industry and others coming in completely unfamiliar.

The logistical challenges start with the very compressed timeline. The application for youth generally does not even open until March, with many SYEP affiliates saying that employers may not know whether or how many interns to expect until June. For some employers, it can be difficult to create meaningful work experiences in a short period of time, and not know if or who will be joining them, or what skills or interests they may have.

“It's very little notice,” says Dina Rabiner, vice president of economic development and strategic partnerships at the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce. “We applied to be a job site in the winter. And now we're in June and we've just found out who we’re getting. Why is that process so long?”

Additionally, the program is largely confined to that six-week period, meaning that all of the work required of employers only results in a very short time with their interns—with no clear path to building those relationships year over year.

"If you are an employer in one of these priority sectors that we're talking about,” says David Fischer, formerly of the Mayor's Office of Youth Employment,5 “how much value are you really getting out of somebody who is working six weeks for 25 hours a week who has no previous real training or understanding of your industry?”

One bright spot is the Work, Learn & Grow program, which helps maintain employer engagement beyond the summer through continued internships, career exploration, and job readiness training. The FY2024 city budget agreed to by Mayor Adams and the City Council includes an additional $22.5 million to add 5,000 slots to expand school-year employment opportunities.

“We always have more students who want to do it than we can serve,” says Tim Lord, co-executive director of DreamYard. “[Work, Learn & Grow] should definitely be an area that they consider for growth.”

Outside of Work, Learn & Grow, however, there are few opportunities to maintain SYEP’s employer relationships throughout the year and from year-to-year.

“The fact that SYEP is a lottery and isn't universal, makes it really hard to build a step-up curriculum,” says Falcone of United Neighborhood Houses. “If young people knew that every time they applied, they'd get a job, and providers knew that, too, then they could actually build a curriculum that advances on itself year after year.”

An SYEP participant working with Reel Works, a nonprofit that trains students in filmmaking. Photo credit to The Studio at Reel Works.

An SYEP participant working with Reel Works, a nonprofit that trains students in filmmaking. Photo credit to The Studio at Reel Works.

Recommendations: 7 Ideas for Strengthening Employer Partnerships with SYEP

- Consolidate employer engagement efforts to reduce duplication and increase efficiency. For many prospective employers, the challenge of engaging with SYEP begins with fielding in-bound requests from every angle—providers, intermediaries, schools, and city agencies. Under the current model, every provider is responsible for recruiting employers and supporting their experience through the program, which duplicates effort and creates confusion among companies. To facilitate more efficient employer engagement, DYCD should consider ways to consolidate contracts in the upcoming RFP to engage networks of providers at the community or borough level and centralize their employer outreach efforts, while expanding partnerships with experienced place- and sector-based intermediaries. This way, intermediaries that already have the trust of employers can feel more confident engaging with the program, while sharing the benefits of those relationships with young people they might not otherwise have met.

- Scale up the smaller programs that have succeeded in building strong relationships with employers. Currently, there are a few initiatives within SYEP that have demonstrated success in recruiting and retaining employer partners from growing and high-wage industries. The schools-based option CareerReady SYEP, where industry-focused intermediaries and participating schools work together to develop internship experiences in close collaboration with employers, has been particularly successful. The city should expand the CareerReady model and invest in scaling up programs like Ladders for Leaders that are already working well for employers in the city’s growth industries.

- Provide employers with significantly more support to make the most out of SYEP. Once employers agree to partner with SYEP, they receive little training on how to design an internship program for teens, align their industry’s unique needs with the requirements of the program, or tailor their program to the specific students that are assigned to them. DYCD should work with the knowledgeable intermediaries that are finding success through programs like CareerReady and Ladders for Leaders to create an expanded toolkit that prepares employers to become effective SYEP hosts. The program should also build the capacity of providers to enhance their employer-focused supports. Among the most important: pre-internship training that can help ensure that students are set up to succeed in their assigned worksites and equipped with helpful industry-specific background knowledge.

- Implement other models beyond the traditional internship that can better fit employer needs. The experimental Summer Bridge SYEP program in 2020 proved that more employers from the tech sector and other fast-growing and high-wage industries provide youth meaningful work experiences if they had options beyond the typical in-person, 25 hour per week supervised internship. DYCD should offer a project-based program similar to the “workplace challenge” model of 2020 for participants of all ages—one that is designed from the outset to meet the state’s definition of “work,” so that participants can receive the full hourly pay rate. DYCD should work with intermediaries to ensure that employers are aware of—and encouraged to create—hybrid and virtual internships when those models are the best fit for a particular company or industry.

- Move up the timeline for pairing students with employers to facilitate a smoother experience. Many SYEP affiliates noted that the timeline for recruiting and then notifying employers of their internship placements via the lottery system poses unnecessary strain on their relationships. Providers typically recruit employers in a rush between December and January, with worksite applications due in February. Then many employers have to wait until late June to learn if they will receive interns only a month later. By shifting the recruitment period for employers to the fall, recruiting SYEP participants earlier in the new year, and making notifications to employers no later than April, the program could provide employers with more guidance and support, and help companies plan at least three months ahead for the summer session.

- Evolve the structure of SYEP to enable year-over-year progression for employers and youth. The six-week lottery system that underpins the SYEP model poses challenges to employer recruitment and retention. Employers are unsure whether students will arrive with even a basic interest in their industry, let alone any relevant skills or previous experiences. Some employers understandably feel that the brief program offers only a minimal reward given the amount of prep work and supervision required, and the absence of any structure to allow interns to gain progressively more experience in the same company or industry from one year to the next. To start, the city should build on the promising expansion of the Career Ready and Work, Learn & Grow programs so that far more students have access to work-based learning experiences during the school year. Ultimately, SYEP should become a universal program, available to all students each year. This move would enable stronger year-over-year planning, provide structure and resources to fully integrate career readiness into education and youth development, and enable both young people and employers to build on their relationships over time.

- Amplify SYEP success stories through a citywide marketing campaign and annual Youth Employment Summit. Although significant challenges to recruiting and retaining employers in the SYEP system remain, the success stories of recent years get little attention. Young people have made innovative contributions to numerous workplaces and many employers have had positive experiences. To elevate these success stories and raise the profile of SYEP among employers, the city should work with advocates in the private sector—and even future cohorts of SYEP interns—to develop a citywide marketing strategy. The campaign should amplify the program’s most inspiring success stories, with a focus on the innovative work done by SYEP participants in the city’s growth industries. This campaign could culminate in an annual Youth Employment Summit, which would bring together youth, employers, providers, and intermediaries to celebrate what’s working, examine opportunities for improvement, and share best practices more widely across the city’s economy.

New York’s Summer Youth Employment Program has come a long way since its creation in 1963, mainly as a way to keep young people “off the streets” in the hot summer months. Today’s record numbers of young participants are gaining valuable paid experience and exposure, often for the first time, to the world of work. For all its successes, however, now is not the time for SYEP to rest on its laurels. With a few relatively modest adjustments that build on elements of the program already in place, SYEP could both serve its participants more effectively and contribute much-needed horsepower to the high-tech and creative industries that are destined to be the engines of the city’s future growth.

Appendix

Endnotes

1 All 2022 Summer Youth Employment Program data provided by the NYC Department of Youth and Community Development.

2 Jonathan Bowles and Charles Shaviro, "NYC's Stalled Retail Recovery," Center for an Urban Future, June 2023.

3 Center for an Urban Future analysis of demographic data on employment from the U.S. Census Bureau 2021 American Community Survey one-year estimates. To examine the racial/ethnic composition of the city’s tech sector, CUF analyzed 17 tech-specific occupations, such as database administrators, web developers, and computer network architects, using data from the 2019 American Community Survey.

4 JobsFirstNYC, "Building and Strengthening Employer Partnerships for Work-Based Learning," April 2023.

5 David Fischer, along with being the founding Executive Director of the Mayor's Office of Youth Employment (MOYE), is also a Senior Fellow at the Center for an Urban Future.

A Ladders for Leaders internship training workshop. Photo credit to PENCIL.

A Ladders for Leaders internship training workshop. Photo credit to PENCIL. An SYEP participant working with Reel Works, a nonprofit that trains students in filmmaking. Photo credit to The Studio at Reel Works.

An SYEP participant working with Reel Works, a nonprofit that trains students in filmmaking. Photo credit to The Studio at Reel Works.