Below is the introduction to Seeking a State Workforce Strategy. Click here to read the full report (PDF).

In aggregate economic terms, New York State has grown and prospered over the last few years. The Empire State has added over 500,000 private sector jobs since 2011, reaching record highs for private sector employment, and the statewide unemployment rate has fallen to 5.9 percent from 8 percent three years earlier.1 Meanwhile, the state has empowered Regional Economic Development Councils and made available hundreds of millions of dollars to help them drive growth, declaring at every turn that New York State is “open for business.”

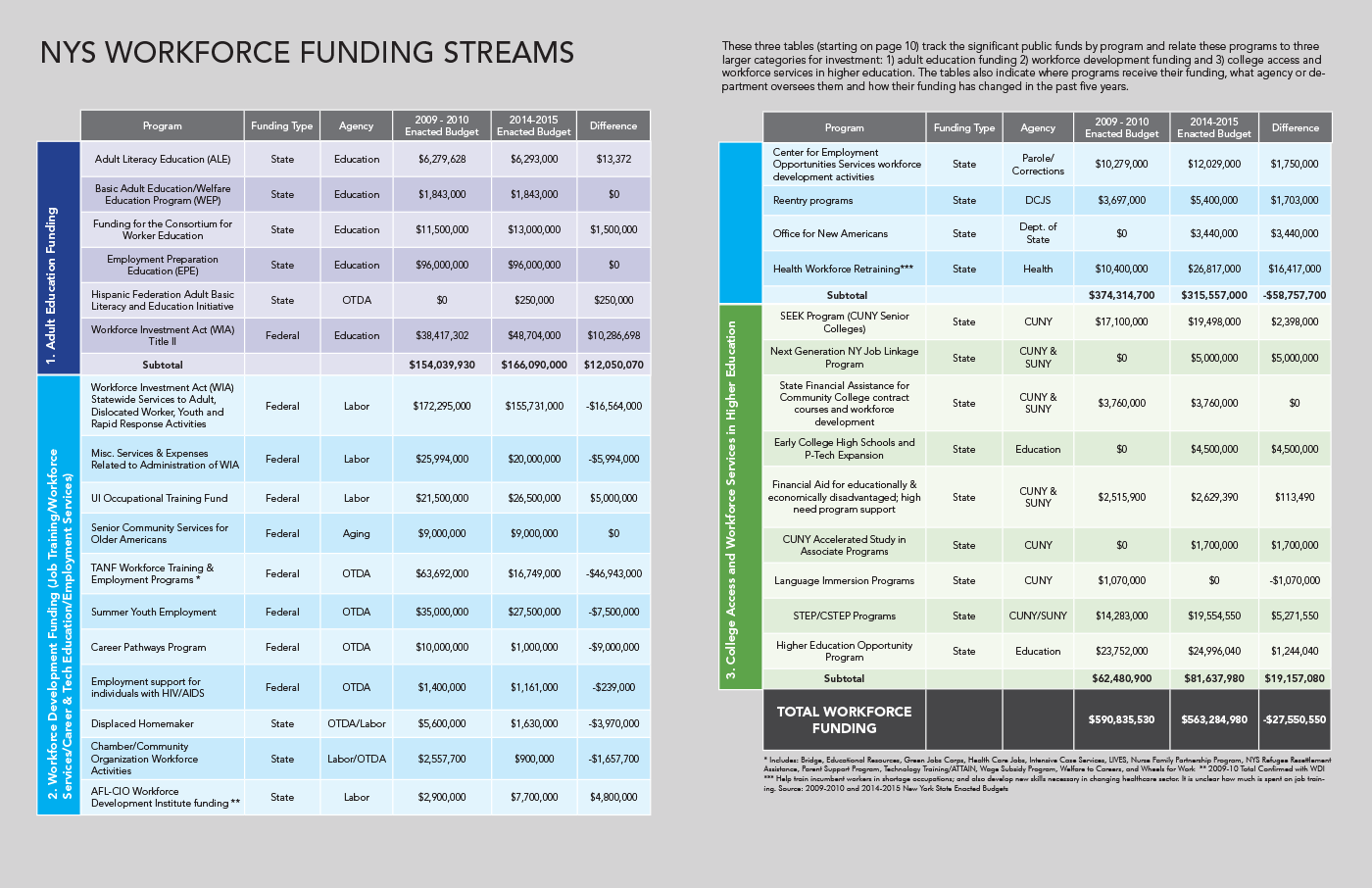

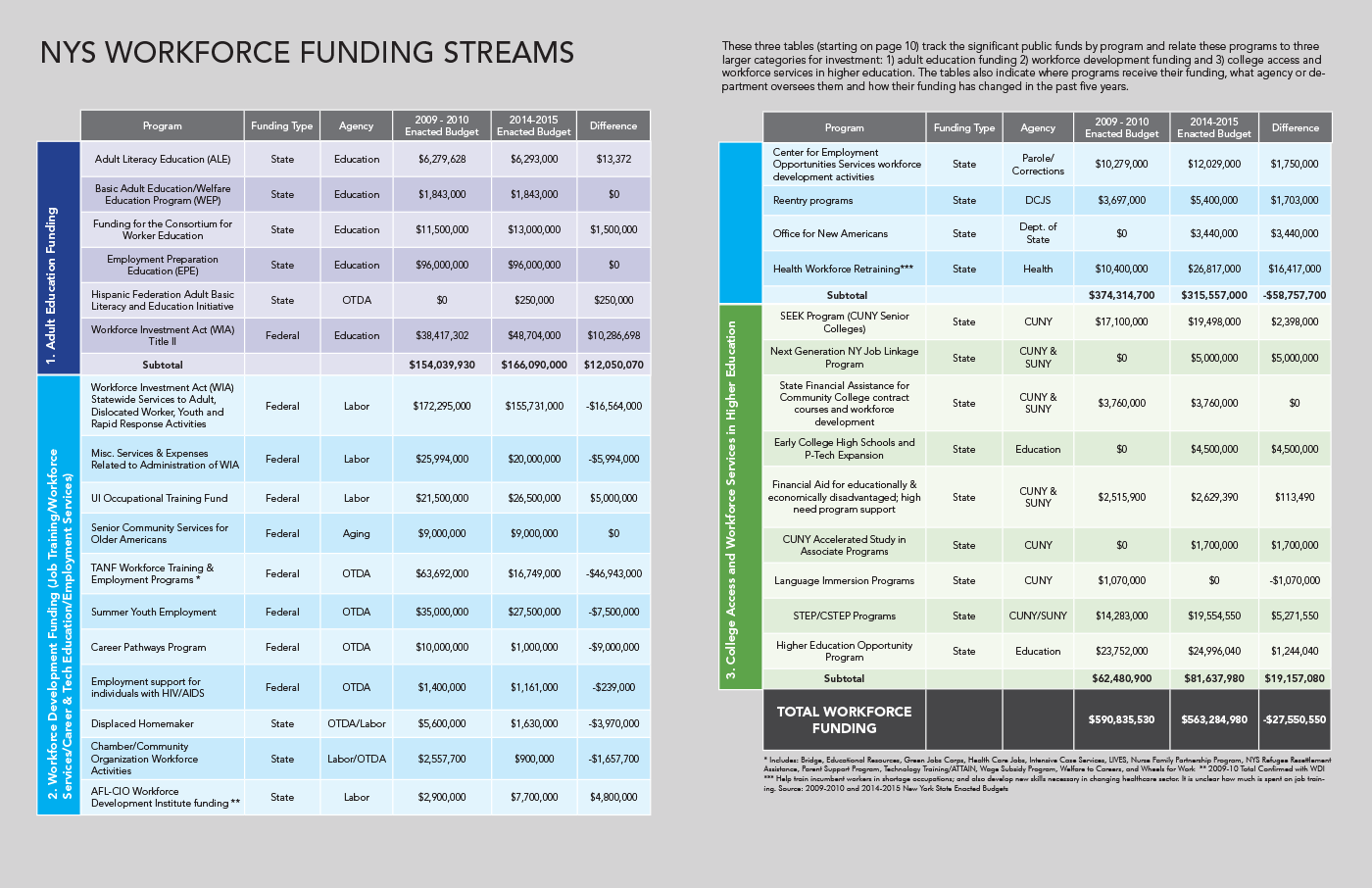

Unfortunately, this commitment to economic growth has not always translated into strong support for workforce development programs that can help ensure that all New Yorkers can share in prosperity. Our analysis of spending on a broad range of workforce services—adult education, job training and employment programs, and college access and related programs to help students connect with jobs and careers—finds that funding for these programs in New York State has fallen by five percent since 2009-2010, with the state spending approximately $563 million on its major workforce-related services in the 2014-2015 enacted budget.

To be clear, deep cuts to federal programs are the cause of the overall decline. In fact, the state has made a modest increase in its own spending since 2009 for these programs, though the totals remain considerably lower than what New York spent a decade ago.2 Nevertheless, state leaders do bear responsibility for the decisions to cut investments in a number of key initiatives that help New Yorkers build skills, gain work experience and connect to career pathways to employment. Among the programs that have suffered are Career Pathways, which help low-skilled New Yorkers gain skills and experience toward securing long-term, career-track employment, and Summer Youth Employment, which provides invaluable early work experience for low-income teens and young adults.

These choices bear troubling consequences in a “knowledge economy” that increasingly rewards skills, credentials, and experience. Without a helping hand from the public sector, too many jobseekers and incumbent workers who don’t have strong educational attainment or strong professional networks will not be able to seize emerging opportunities or partake in the benefits of overall growth. Exacerbating the problem is the absence of any clear strategy to raise the skills of New York’s entire workforce—there should be no such thing as a “spare” New Yorker—an omission that stands in contrast to other states in similar political and economic circumstances.

The ongoing disconnection of workforce activities from economic development represents another significant problem. The ten Regional Economic Development Councils (REDCs), created and championed by the governor as a key element of the state’s economic growth strategy, have not made significant investments in employment and training. In fact, our analysis found that despite a specific workforce focus within each local REDC plan in 2014, only about $7.8 million—just over 1 percent of the $709.2 million available through the REDC Consolidated Funding Applications (CFA)—is geared explicitly toward helping New Yorkers find jobs or access skills training.3

New York’s workforce system is a complicated entity that engages nearly a dozen state agencies and myriad funding streams originating at the federal and state levels, and operates on the ground in ten economic development regions, 33 designated workforce investment areas, community-based organizations, labor unions and 62 counties. This report lays out the state of New York’s aggregate expenditures on employment and training services, and tracks the change in funding levels in the enacted budgets from 2009-10 to 2014-15 (see p. 10). It also focuses on how the state needs to define, communicate, invest in, and implement a consistent strategy to increase its supply of skilled workers. This means investing in the full range of educational pathways and training mechanisms to boost the skills of all of its residents, to helping employers find the talent they need to prosper, and in instituting thoughtful policies that remove barriers to achieving a high quality, responsive workforce system.

Labor market trends suggest that policymakers should move quickly. Economists forecast that employment in New York State will continue to grow throughout the remainder of this decade: all told, the state is projected to add more than 840,000 jobs between 2010 and 2020. A significant share of those emerging jobs will require education beyond high school: as Governor Cuomo’s 2014 reelection campaign plan “Moving the New New York Forward” notes, economists forecast that by 2020, 69 percent of all jobs in the state will require postsecondary education.4 Too many New Yorkers now in the workforce lack the educational credentials to compete for those positions, particularly in communities that have never recovered from the disappearance of manufacturing jobs, or economic decline over the past 50 years.

The plateauing of educational attainment might help explain why average wages in New York actually have declined in real terms over the past few years. In 2009, the average working New Yorker earned $866.43 per week, equivalent to $946.27 in 2013 dollars. But average weekly wages in 2013 were only $940.32, meaning that workers’ real purchasing power fell even as job growth accelerated.5 The New York State Department of Labor (NYSDOL) has found a very significant “wage premium” for state residents who hold higher education degrees versus those with only a high school degree or equivalency ($60,500 compared to $27,200).6 Additionally, those with more education fare better in economic downturns, have increased family stability, and health outcomes, among other benefits.7

With the recent passage of the federal Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA), and examples of local innovation in training and employment services from Long Island to the Finger Lakes, the moment is ripe for Albany to think more holistically about statewide workforce policies, pipelines, and investments. Competitor states such as California, Massachusetts and Minnesota have made clear policy choices and substantial investments in training, to the benefit of both workers and employers within those states. New York would be wise to review what those states have done and consider similar action.

This report calls for state leaders to make a strong new commitment to helping New York’s workers and businesses add the skills they need, with a compelling strategy and smart investments to sustain and accelerate prosperity in the Empire State. In developing a statewide workforce strategy that effectively serves employers and jobseekers, New York policymakers must provide leadership to:

-

Thoughtfully connect workforce investments to the initiatives and priorities of statewide, regional, and local economic development;

-

Focus policy and emphasis on the full pipeline of workers—including not only the K-12 system and college, but also adult basic education and incumbent worker training; and

-

Fund the system at a level that demonstrates its priority status as a component of economic development.

1 New York State Department of Labor. “NYS Economy Adds 30,100 Private Sector Jobs in December 2014 and Statewide Unemployment Drops to 5.8%.” January 22, 2015. Retrieved from http://labor.ny.gov/stats/pressreleases/pruistat.shtm

2 See “A Thousand Cuts,” Center for an Urban Future and New York Association of Training and Employment Professionals, 2007, online at /pdf/A_Thousand_Cuts.pdf. The comparison is not exact, as that report and this one utilized different methodologies.

3 “Regional Economic Development Councils: Regional Partners, Global Success 2014.” Retrieved from http://regionalcouncils.ny.gov/assets/documents/REDC_2014_Guidebook.pdf

4 Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce, “Recovery: Job Growth and Education Requirements Through 2020,” June 2013. Online at https://georgetown.app.box.com/s/kg8r28e48gsaw8ypplxp. Cited in Governor Andrew M. Cuomo, “Moving the New New York Forward,” October 2014.

5 New York State Department of Labor. Average Hourly and Weekly Earnings. Retrieved from http://labor.ny.gov/stats/ceshourearn2.asp; inflation adjustments calculated on http://www.dollartimes.com/calculators/inflation.htm

6 New York State Department of Labor, Division of Research and Statistics, Bureau of Labor Market Information, “Analysis of New York State’s 2010-2020 Occupational Projections and Earnings by Education Level,” April 2013. Retrieved from https://labor.ny.gov/stats/PDFs/Analysis-of-2010-2020-Occupational-Projections-and-Wages.pdf

7 John Irons. “Economic Scarring: The Long-Term Impacts of the Recession.” Economic Policy Institute. September 30, 2009. Retrieved from http://www.epi.org/publication/bp243/.

The above was the introduction to Seeking a State Workforce Strategy. Click here to read the full report (PDF).