The following are the introduction and recommendations to Bridging the Disconnect.

Read the full report (PDF).

View the charts and tables from the report.

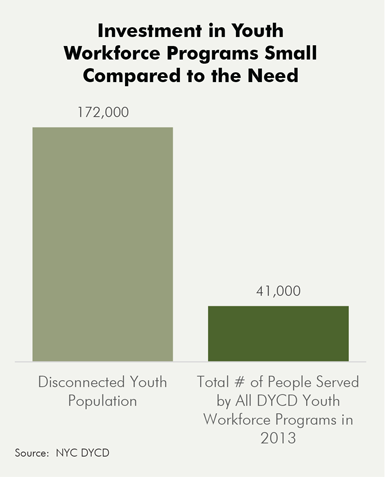

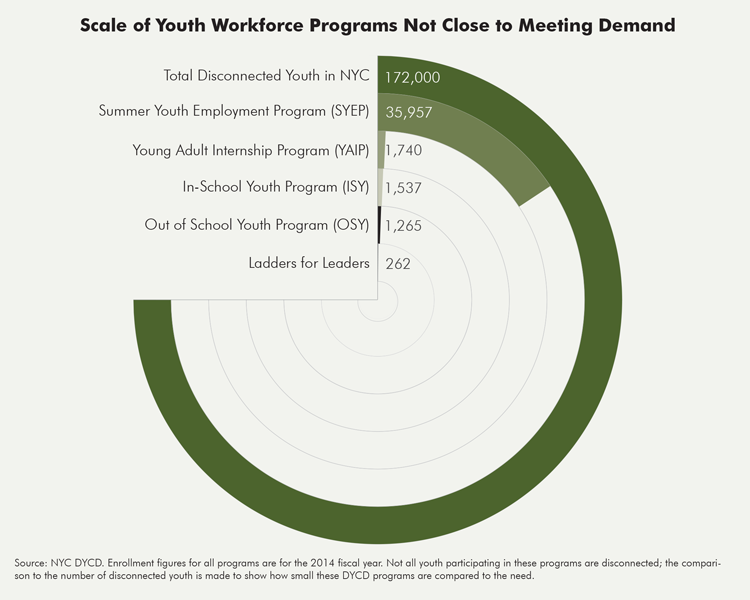

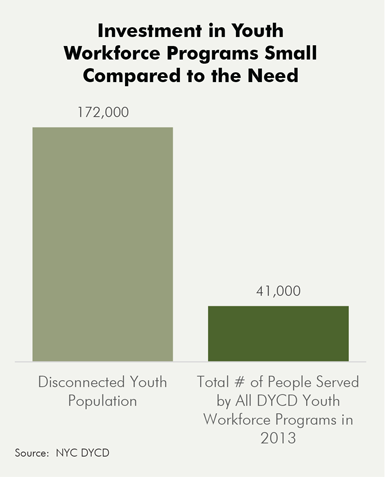

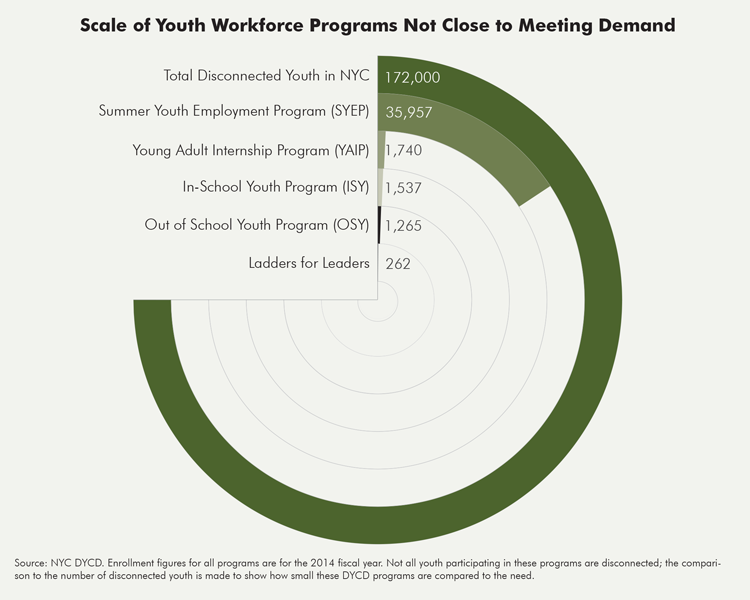

New York City is facing a youth employment crisis, with unprecedented numbers of young people reaching adulthood without the skills or experiences to secure career-track jobs that pay a living wage. Since 2000, the percentage of 16 to 24 year olds across the five boroughs participating in the labor market has fallen from 45 percent to 29 percent, while the unemployment rate for this group has spiked from 13 percent to 20 percent. Alarmingly, approximately one out of every five New Yorkers in this age bracket—an estimated 172,000 in all—are neither working nor in school, by far the largest number of any city in the United States.

Despite the magnitude of the problem, New York City’s youth workforce development system falls far short of what is needed. Youth-focused workforce programs reach only a tiny fraction of the young adults who could benefit from employment and training services. At the same time, too many of the city’s existing youth workforce development programs are deeply flawed and do little to help young people build skills and connect with decent-paying jobs.

The five workforce programs run by the city’s Department of Youth and Community Development (DYCD), the city’s primary youth workforce agency, served fewer than 41,000 young people last year. DYCD’s signature initiative, the Summer Youth Employment Program (SYEP), enrolled 35,957 young people in 2013 but had to turn away almost three times that number due to insufficient capacity. Perhaps even more alarming, DYCD’s four other workforce programs served fewer than 5,000 youth combined last year.

But while the city’s youth workforce system could undoubtedly benefit from more resources, it also needs a major restructuring. Indeed, as this report documents, the three city agencies that provide the bulk of youth workforce development services in the city—DYCD, the Department of Small Business Services (SBS) and the Human Resources Administration (HRA)—all have major shortcomings when it comes to helping young New Yorkers gain the education, skills and experiences necessary for career-track employment.

For instance, while DYCD’s Summer Youth Employment Program provides structured activity for six weeks over the summer and some income for those enrolled, most youth advocates believe it is poorly designed and does not do enough to help young people prepare for the world of work. SYEP lacks strong connections to employers, as do DYCD’s other programs. Virtually all of the agency’s workforce programs are ill equipped to serve youth with the most serious barriers to employment and career success, including those in foster care, court-appointed and homeless youth, those with disabilities, recent immigrants and LGBT youth. As for the other primary workforce agencies, while SBS and HRA provide workforce services to tens of thousands of young adults every year, their initiatives are largely misaligned to the developmental needs of young people, many of whom require substantial assistance before they are ready to hold and keep a job.

With fresh leadership now in place at DYCD, SBS and HRA, as well as a newly created Office of Workforce Development tasked with coordinating city workforce policy, there is a unique opportunity to address the youth employment crisis and improve publicly supported services to help young people transition into the labor market. Doing so could help Mayor de Blasio fulfill his goals of attacking income inequality and putting more New Yorkers on the path to the middle class.

In recent years, several studies have shed light on the troubling employment and educational outcomes for young adults and the high number of disconnected youth in New York City. This report builds upon those research efforts by evaluating how New York City has responded to the problems of youth disconnection and difficulties gaining traction in the labor market. Our report assesses the strengths and shortcomings of the city’s youth workforce development programs, identifies the challenges facing administrators and practitioners, and offers recommendations to address the system’s many flaws and deliver stronger outcomes for youth and greater return on public and philanthropic investment. Because the de Blasio administration has only begun to develop its own workforce agenda, our assessment focuses on how the city’s youth workforce development system was structured and managed over the past decade.

Based on eight months of research, the report is informed by interviews with over 60 youth workforce development practitioners, philanthropic leaders, city officials, employers and thought leaders in New York City and across the country. We also compiled and analyzed administrative data from the city agencies that manage programs serving youth, and considered best practices both locally and nationally.

Our conclusion is that a new level of focus and a new approach is desperately needed to power improvements to the city’s youth workforce development system.

There’s little doubt that New York is facing a youth employment crisis. In 2012, the unemployment rate for young adults ages 16 to 24 was 18.6 percent—more than double the citywide average, and twice as high as for any other age cohort. Last year, only 29 percent of 16 to 24 year olds were employed or seeking work. In 2012, among the nation’s 100 largest metro areas, New York City ranked 92nd in the rate of 16-19 year olds employed, and 97th for 20-24 year olds.

For youth, unemployment and marginalization can have long-term consequences. Research has shown that employment is “path dependent”: individuals who work in their mid-teens are more likely to work in their late teens, and more likely to have steady employment and higher earning power into their 20s and beyond. The converse is also true: individuals who aren’t employed during their teens are less likely to work consistently as they transition into adulthood. And while the recent sluggish hiring climate is part of the problem, the reality is that too many young adults lack the educational foundation, demonstrable skills and work experience that today’s employers demand.

Sadly, the city’s response to the youth unemployment crisis over the past several years has been woefully inadequate. The Bloomberg administration deserves credit for its commitment to improving the city’s public school system, and for expanding the number of Career and Technical Education (CTE) schools and launching promising new programs like the Young Men’s Initiative, a cross-agency attempt to improve outcomes for young African-American and Latino males. But its failure to make meaningful new investments in workforce development programs targeting unemployed and disconnected youth and young adults holds potentially dire consequences for years to come.

“The city’s youth workforce development infrastructure has not grown in relation with the scale of the crisis,” says Randy Peers, executive director of Opportunities for a Better Tomorrow (OBT), a Brooklyn-based organization that provides workforce services to youth. “The investments that target that population are minimal. We have some good programs, but we just don’t have the resources to take them to scale.”

This is most apparent at DYCD, the city agency with primary responsibility for workforce development programs serving teens and young adults. While overall city expenditures increased by 14.6 percent between fiscal years 2008 to 2013, DYCD’s expenditures declined by 15.5 percent.

In 2013, DYCD’s signature workforce initiative, the Summer Youth Employment Program (SYEP), provided summer jobs to just 35,957 individuals, 17 percent fewer than in 2008 (when its enrollment was 43,113) and 29 percent less than in 2000 (50,499). The declining enrollment numbers contrast with increasing demand. Indeed, 73 percent of the 135,388 applicants last year were turned away. Between 2010 and 2013, DYCD could not place more than 410,000 applicants to SYEP. Given the difficulties youth face in the labor market, it’s certain that the vast majority did not find work through other channels.

But the shortfall is by no means limited to SYEP. In fact, DYCD’s other four workforce programs, Out-of-School Youth (OSY), Young Adult Internship Program (YAIP), In-School Youth (ISY) and Ladders for Leaders, served only 4,372 young people combined in 2013—approximately 40 percent fewer than in 2010. The two DYCD workforce programs focused on disconnected youth—the Out-of-School Youth program (OSY) and Young Adult Internship Program (YAIP)—combined to serve just 2,835 New Yorkers last year, less than two percent of the city’s estimated disconnected youth population. DYCD’s In-School Youth (ISY) program served 1,537 young people, while Ladders for Leaders, a highly regarded internship initiative, served just 262 youth last year. Although its enrollment increased from 190 to 262 over the past four years, a mere 11 percent of young people who applied to Ladders for Leaders last year were placed into internships.

There are other indications that the city’s youth workforce programs reach only a small percentage of those in need of services. While the bulk of New York’s youth workforce services are delivered by nonprofit and for-profit service providers, even many of the largest and most highly regarded organizations have fairly limited capacity. For instance, The Door, a Manhattan-based group, serves roughly 500 and OBT serves approximately 700.

While limited resources are a significant constraint, there are also serious flaws with the way the city’s youth workforce programs are structured and delivered. The core shortcoming of the city’s youth workforce development system is that services are poorly aligned to the life circumstances and developmental needs of the young people who need assistance.

The majority of young New Yorkers who could benefit from city workforce development services have at most a high school degree or equivalency, have limited or no work experience and face significant barriers to employment—from chronic health issues to unstable housing arrangements. Most simply aren’t ready to succeed in a workplace, and need assistance that goes well beyond finding a job. Yet, too few of the city’s workforce programs are structured with all this in mind. Most do not offer opportunities for young people to explore career options, provide youth with sufficient time to build skills and prepare for employment or furnish them with a range of services.

A related problem is that the city’s youth workforce system is particularly ill suited to help the large and growing number of high-need youth. Immigrant youth, those in foster care, youth with disabilities, youth involved in the justice system, homeless and LGBT youth are all over-represented among New York’s disconnected population and typically face more significant barriers to employment. Yet these groups often find little assistance from the city’s publicly funded workforce programs. Indeed, their more serious barriers represent a disincentive for providers to enroll them, because they are less likely to meet the required outcomes for which the city reimburses on performance-based contracts.

The federal Workforce Investment Act (WIA), which has guided the nation’s job training and workforce preparation programs since 1998, has not been good for youth-focused workforce development. WIA prioritizes and rewards quick attachment to the labor force: in fact, job placement is the only career outcome on which the federal government evaluates each area’s WIA performance. Yet, effective youth workforce services aren’t intended to make a short-term job match, but rather to put in place a foundation for long-term labor market success. Organizations cannot use WIA funds to pay for services that might better support long-term outcomes, such as fellowships, subsidized internships or opportunities to learn about different possible career paths and better define their interests and goals. Worse, WIA-funded contracts create a perverse incentive for organizations that offer youth workforce services: by rewarding only job placement or quantifiable literacy gains, and limiting the time providers have to deliver these results, they encourage providers to avoid enrolling those with the deepest educational and socio-emotional deficits. Instead, many organizations reluctantly “cream,” enrolling the most job-ready individuals. The new Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act, signed into law by President Obama in July 2014, should address a number of these issues—if city leaders are prudent in taking advantage of their new options under the law.

While the federal policy context has not been helpful, much of the problem lies closer to home, with the city’s youth workforce system and the three main city agencies—DYCD, SBS and HRA—that deliver workforce services to youth and young adults.

DYCD oversees an array of youth initiatives, including afterschool programs, literacy programs and school-based community centers. But it is also the only city agency specifically charged with designing and managing programs that prepare young New Yorkers for employment and career success. Unfortunately, the consensus of the youth practitioners and policy experts we interviewed is that the agency’s workforce development programs frequently fall short of helping young people build skills, determine their career goals or gain valuable workplace experiences.

“DYCD is not an employment agency,” says Lowell Herschberger, director of career and educational programs at Cypress Hills Local Development Corporation. “They do fabulous work around K-12 and afterschool programs, but there’s nobody there to hold together a system for disconnected youth.”

Two of DYCD’s workforce initiatives—Ladders for Leaders, a program track within SYEP, and the Young Adult Internship Program (YAIP), generally draw praise from the field. Ladders for Leaders is the sole DYCD effort that boasts truly strong employer connections, and YAIP is alone among DYCD’s workforce programs in having received a rigorous quantitative evaluation that showed strong results. The agency also deserves credit for making some key changes to SYEP over the past decade, including increasing the number of job placements with private sector employers, expanding the number of slots set aside for vulnerable youth and beefing up the educational training that is provided to participants.

But the balance of DYCD’s workforce portfolio is more problematic. Most of its programs lack strong connections with employers, a crucial flaw if the goal is to prepare young people for the world of work. Workforce observers and practitioners assert that DYCD has been less willing than SBS and HRA to adjust programs in response to labor market changes and push their vendors to change their practices and achieve stronger outcomes. The agency’s In-School-Youth (ISY) and Out-of-School-Youth (OSY) programs have not been evaluated to measure impact. And while SYEP provides youth and young adults with jobs that would not otherwise be available to them, most workforce experts criticize the program for offering low-value work experiences with no connection to participants’ school experiences or career interests. “SYEP is just warehousing kids in the summer,” says one workforce expert. “You have kids sitting in auditoriums with nothing to do. The kids get no training. They develop bad habits.”

SBS, which manages workforce programs for adults and dislocated workers, comes in contact with tens of thousands of young adults every year through its 18 Workforce1 Centers across the five boroughs. But these centers are geared to serve job-ready individuals and do not offer the specialized services or longer time frames that most young adults need.

HRA, the city’s welfare agency, provides workforce services to thousands of 18-24 years olds who receive public assistance and are required to enroll in its Back to Work program. But its “work-first” orientation is not well suited for young adults on the welfare rolls, a majority of whom lack a high school diploma and would be better served with programs that help connect them with education and training.

“TANF is the biggest funding stream and HRA is the biggest service provider,” says workforce consultant Celeste Frye, “but they don’t focus on young adults, even if they have young adults in their portfolio. There should be more TANF-funded services that are geared for young adults.”

Making matters worse, while DYCD, SBS and HRA each have their own problems in how they deliver workforce services to youth and young adults, the agencies also have failed to align their programs to offer integrated services for young New Yorkers in need. At the same time, public youth workforce contracts actually create disincentives for nonprofit providers to work collaboratively to provide the continuum of services young people need in order to become self-sufficient. As a result, most individuals receive only the services that any one provider may offer—not the services they most need. Only those programs that draw from multiple funding streams, usually including philanthropic support as well as public contracts, and have the resources to manage the resultant administrative burdens, can offer the holistic set of services most likely to make the difference for high need youth.

For all these problems, however, a number of vital pieces are in place that could allow the city to make significant progress in addressing the youth workforce crisis. The city boasts a number of effective youth workforce providers, from community-based organizations to nationally recognized models such as FEGS, Opportunities for a Better Tomorrow (OBT) and The Door among others that utilize blended funding from public and private sources. The city is also home to JobsFirstNYC, a youth-focused intermediary that advocates for policy change and best practices and has launched several highly promising pilot initiatives, as well as two other organizations, the Youth Development Institute and Workforce Professionals Training Institute, that deliver technical assistance to provider organizations.

New York also benefits from a particularly strong philanthropic sector that supports many of the best youth workforce providers and funds innovative approaches that restricted government dollars cannot pay for. Indeed, New York City enjoys more foundation support for employment and training programs than anywhere else in the U.S., thanks in large part to the efforts of a philanthropic collaborative known as the New York City Workforce Funders. Collectively, these funders invested approximately $28 million in youth-focused workforce programs and related services in 2013—an amount larger than the city’s WIA Youth allocation from the federal government.

There are also a number of encouraging signs from government. The FY 2015 city budget approved in June included a new investment of $15.2 million from the City Council that will enable an additional 10,700 young people to participate in SYEP this summer. In his first State of the City address in February, Mayor de Blasio pledged a new focus on job training and skills building. Shortly thereafter, he convened the Jobs for New Yorkers Task Force to provide ideas for overhauling city workforce development programs, and created the Office of Workforce Development to better coordinate the many city agencies and offices involved with job training and workforce preparation programs. The federal government has taken a key step as well, passing the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) with overwhelming bipartisan support. WIOA’s changes should make it easier for the city to overhaul work-focused education, training and employment services for younger New Yorkers.

This is a good start. But so much more is needed to improve and expand the city’s youth workforce development system.

More than anything, Mayor de Blasio and the City Council must make tackling the youth employment crisis a top priority. With more young people than ever unemployed, underemployed or stuck in low-wage, dead-end jobs, the de Blasio administration should take bold steps to address the problem and set ambitious goals for reducing youth unemployment across the five boroughs.

One vital step is simply to expand the capacity of programs to reach more youth and young adults—a significant challenge, given that WIA Youth funds for New York City have plummeted from $43.3 million in 2000 to $21.4 million in 2013. But as Mayor de Blasio demonstrated with his successful effort to create universal pre-kindergarten programs, and as former Mayor Bloomberg showed with his Young Men’s Initiative, focused mayoral leadership can go a long way toward identifying public and private funds for important programs.

But since the problem goes well beyond resources, administration officials also must commit to making a number of structural changes that could greatly improve how services are delivered to youth and young adults in New York.

There is no shortage of possible innovations that could improve practice and deliver greater value for youth. As this report details, New York City can learn from the examples of cities like Boston, Philadelphia and Los Angeles that have placed greater emphasis on supporting youth transitions into the workforce. Each of these examples offers lessons—around innovative governance, employer engagement and provider collaboration systems—which local policymakers would do well to consider.

City officials should also learn from what SBS did during the Bloomberg administration to improve adult workforce development outcomes. The agency brought new scale and standardization to employment services by creating a network of Workforce1 Career Centers across the five boroughs. Partnerships with private funders and the Center for Economic Opportunity helped SBS create sector-focused Workforce1 Centers that deepened engagement with employers, developed new models for training incumbent workers at small and mid-sized businesses, and leveraged resources through partnership with community-based organizations including libraries, CUNY campuses, nonprofit organizations and labor unions. The aggregate result was a vastly improved system that delivered real value to hundreds of thousands of residents and countless city businesses. The number of New Yorkers placed into jobs rose from 500 in 2004 to over 29,000 last year, showing how sufficient attention and investment can power dramatic gains.

The youth side is overdue for similar progress. Under a more effective youth system, city agencies could create a more seamless experience for youth and reduce compliance burdens for providers by coordinating case management and building shared systems. A central entity—most likely the newly created Mayor’s Office of Workforce Development—could serve to set strategy, analyze how practitioners can best meet labor market needs and support stronger relationships with employers.

With Mayor Bill de Blasio focused on improving the advancement prospects of all New Yorkers, and a new set of commissioners in place with no obligation to the old ways of doing business, now is the moment to commit anew to supporting New York City’s youth as they transition into working adulthood. With employer expectations steadily rising, there is no time to waste: before the end of this decade, two out of every three new jobs that will be created in the United States will require training beyond high school, and work experience might be more important still.