This is an excerpt. Click here to read the full report (PDF).

New York City has never been a particularly easy place for teenagers and young adults to break into the workforce. Even during the boom years of the 2000s, the city’s unemployment rate for teens between the ages of 16 and 19 hovered just under 20 percent. By the end of 2010, it had risen to 40 percent.

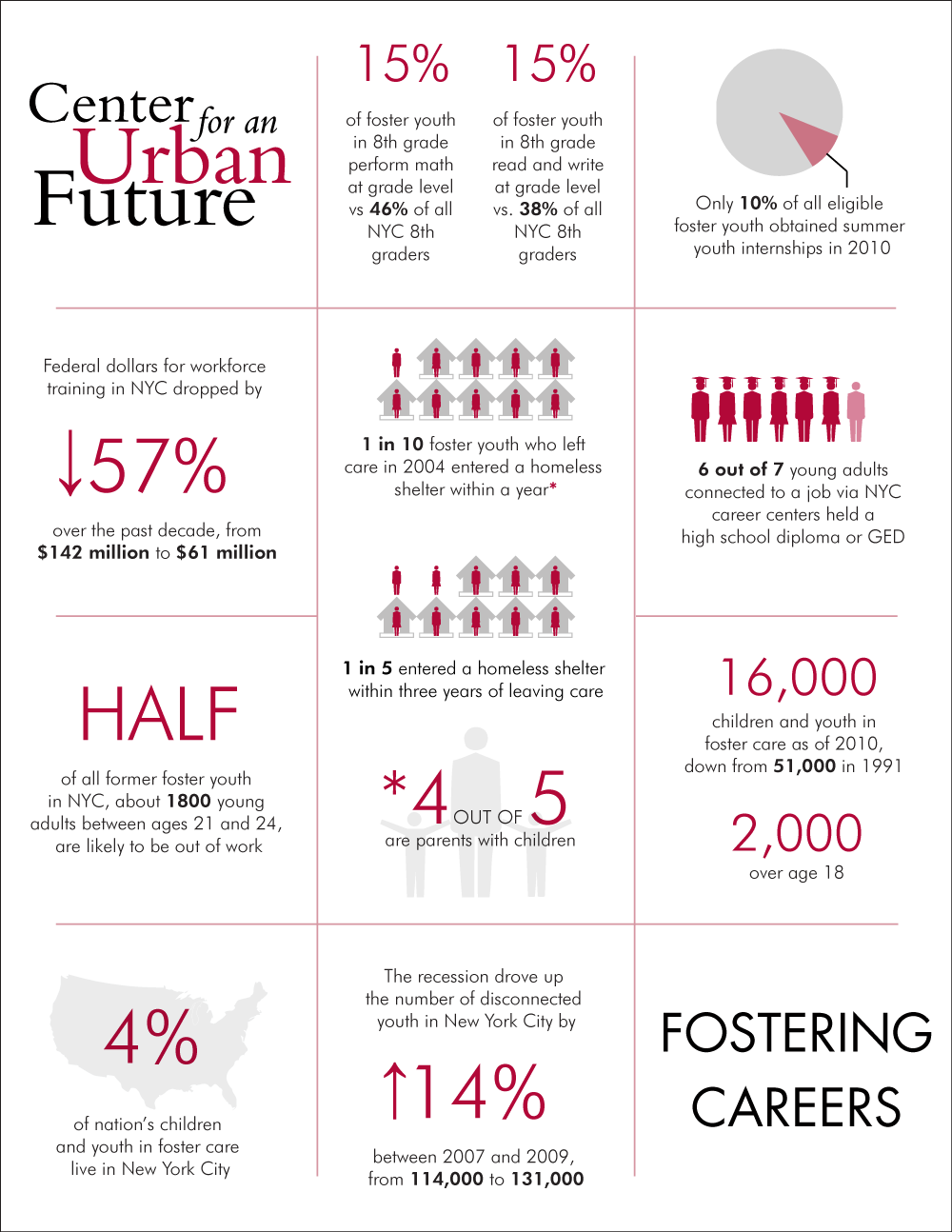

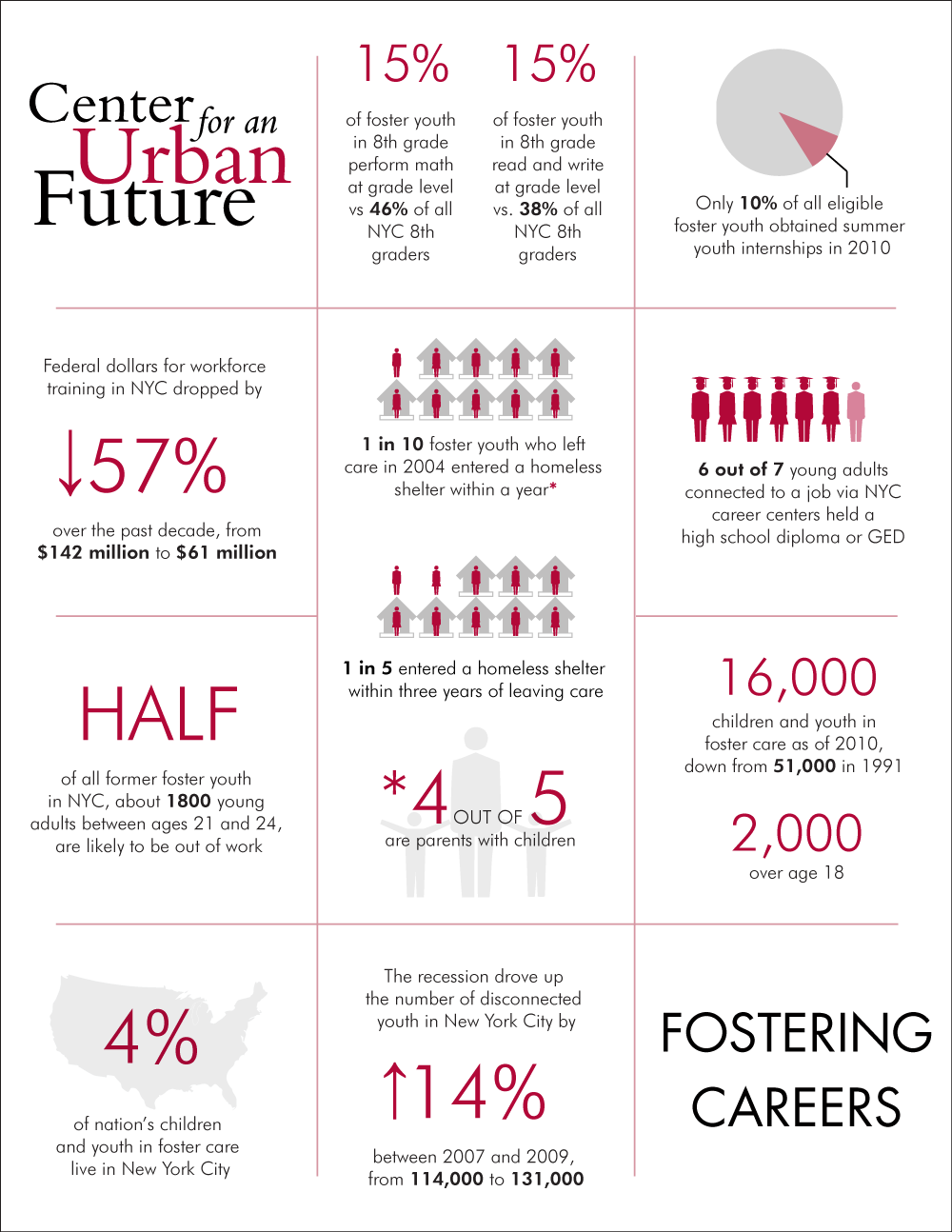

As shocking as these numbers are, however, young people aging out of the city’s foster care system appear to be faring even worse. Based on dozens of interviews with child welfare practitioners across the five boroughs, we estimate that that no more than half of the young people who have recently left the foster care system have jobs at any given time. With nearly 1,000 foster youth aging out of the system every year, that means that close to 500 young people each year are failing to connect with the world of work.

The tragic result is that far too many foster youth go from being minor wards of the state to adult wards of the state, with high rates of incarceration, public assistance use and homelessness. According to the Administration for Children’s Services (ACS), one out of ten foster youth in New York City who left foster care in the mid-2000s entered a homeless shelter within the year. And within three years, one of five entered a homeless shelter.

These dismal outcomes might very well be different if more foster youth were able to access—and hold onto—jobs. But, as we show in this report, not enough is being done to help foster youth connect to jobs and careers. While there is a lot that is right with the child welfare system today, neither the city agencies that oversee the child welfare system nor the private foster care agencies that provide direct services to foster youth are adequately equipped to help young people who are aging out of the system to succeed as adults. And the greatest shortcomings are with assisting foster youth to prepare for the workforce.

* * *

This study takes an in-depth look at the challenges foster youth have in getting and keeping jobs as adults and examines what the various players in the city’s foster care and workforce development systems are—and aren’t—doing to help young people transition from foster care into adulthood. It offers a range of recommendations on what could be done to improve employment and educational outcomes of young people aging out of the system. The study is based on an extensive data analysis as well as interviews and focus groups with more than three dozen experts and practitioners in foster care, workforce development, youth development and education.

As of 2010, there were approximately 16,000 young people in foster care in New York City, of whom 7,000 were between the ages of 14 and 21 and 2,000 over the age of 18.1 Foster youth must leave care by age 21, although many leave earlier. Over the past decade, an average of 918 young people have aged out of the foster care system each year—with a high of 984 in 2008 and a low of 832 in 2005.

While it’s clear how many New Yorkers move out of the system every year, unfortunately no one—not the city and not the city’s foster care agencies—tracks employment outcomes among former foster youth in New York City. But though data is lacking, the long list of foster care professionals we interviewed were in broad agreement: an alarmingly high number of foster youth are not working.

“It’s quite apparent to me that former foster children fare poorly in the job market,” says Richard Altman, executive director of the Jewish Child Care Association (JCCA), one of the city’s largest foster care agencies. “Children in foster care are behind on every indicator for future employment success once they leave care.”

“Of foster care alumni, the number who fail to find stable employment is probably 50 percent or higher—at least”

Most of those we spoke with estimated that around 50 percent of their former clients are unemployed. “Of the foster care alumni removed from family and aging out of care, the number who fail to find stable employment is probably 50 percent or higher—at least,” says Jeremy Kohomban, executive director of Children’s Village and one of the nation’s most respected foster care experts.

Foster youth are not the only young people who struggle in today’s labor market. The likelihood that a teenager can find employment has dropped steadily over the past decade due to shifts in the national economy, and the recession has only worsened and accelerated the trend. One particularly troubling indication of how badly young people in New York City are faring is that in 2009, the most recent year for which the city has data, there were roughly 177,000 young people between the ages of 16 and 24—almost one in five New Yorkers in this age group—who were neither in school nor in jobs. Three out of four of these youth have been jobless for a year or more and are referred to as “disconnected” from school and work.

Most of these “disconnected” young people have never gone through New York’s foster care system. However, experts who study disconnected youth have found that teenagers in foster care are much more likely to disconnect from school and work than other youth. Indeed, foster youth are greatly over-represented in every adult population that is considered dysfunctional—prison, welfare, homeless shelters.

Although there is no official data on employment outcomes of foster care youth in New York, studies at the national level confirm the anecdotal information we have gathered. The Midwest Evaluation of the Adult Functioning of Former Foster Youth (Midwest Study) is an ongoing cohort analysis that has been tracking a sample of young people from Iowa, Wisconsin, and Illinois as they transition out of foster care into adulthood. The researchers—a team involving Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago; Partners for Our Children at the University of Washington, Seattle; the University of Wisconsin Survey Center; and the public child welfare agencies in Illinois, Iowa, and Wisconsin—found that youth in the study struggle more than other youth. Half were unemployed at age 21 and the same share was unemployed three years later. Of those who were employed, almost a third was working part-time. Of those who were unemployed, one out of six was incarcerated.

If, as in the Midwest study—and as we heard in our interviews—half of the former foster youth in New York City are unemployed at any given time, then about 1,400 of the nearly 2,800 alumni between the ages of 21 and 24 are likely to be out of work.

One chronic effect of unemployment is loss of housing and homelessness. Here we do have some information on what foster youth experience in adulthood. Dennis Culhane, a researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, matched data held by the Administration for Children’s Services (ACS) and the Department of Homeless Services (DHS). He found that 13 percent of youth over the age of 17 who left the foster care system in 1996 entered a city homeless shelter within three years. When ACS and DHS revisited the study in 2008 with a similar methodology (looking at youth who left care ages 16 and older), they found that the situation had worsened: of all youth ages 16 and older who left care in 2004, 21 percent had entered a DHS homeless shelter within three years. In less than a decade, the likelihood of homelessness had increased by more than one-third.

There are clear reasons why foster youth are having difficulty entering and staying in the workforce. Perhaps the clearest and most unambiguous problem is in education. Employers are increasingly likely to hire only high school graduates, making low-literacy youth less employable each year. According to data we received from the New York City Department of Education, only 15 percent of foster youth in 8th grade have English or math skills at or above grade level—roughly one-third the proportion of all 8th grade students.

A primary cause of poor school performance is multiple foster care placements. The average youth who ages out of care has moved from one home to another seven times. Each time the youth is likely to change schools and miss days or weeks of class, and each time fall behind a little more. Practitioners in the field report that multiple placements cause other problems too: a wariness and mistrust of adults, emotional trauma that compounds the trauma of being removed from parents, lack of close connections and socialization with other youth. The effect on work habits can be highly destructive. “While an employer might understand and be sensitive to these issues, their expectation is that employees come ready to work, that they will be punctual, in attendance consistently and that they approach work with a focused and positive outlook,” says Courtney Hawkins, vice president of education and youth services at at F.E.G.S., one of the largest social service agencies and providers of foster care services in New York. “And while many of us take these work characteristics for granted, they’re often a challenge for foster care youth.”