Testimony of Thomas J. Hilliard

Senior Fellow for Economic Opportunity, Center for an Urban Future

Before the New York State Assembly Committee on Higher Education

on The Excelsior Scholarship and the Enhanced Tuition Awards Programs

December 12, 2017

Good morning, Chairperson Glick and members of the Assembly Committee on Higher Education. I am Tom Hilliard, Senior Fellow for Economic Opportunity at the Center for an Urban Future, a non-partisan public policy think tank based in New York City. The Center develops public policy strategies to strengthen economic opportunity and economic growth across New York State. Helping colleges and universities serve their students more effectively is key to both economic opportunity and growth. Last week, we published Degrees of Difficulty, a study that identified college completion as an urgent priority for New York City and documented key reasons why students fail to complete their college education.1

College completion is not just one educational priority among many. It is a determining factor in whether our educational system leads to upwardly mobile careers or to disappointment, stagnation, and wasted expense. However, our report shows that an alarming number of New Yorkers who enroll in public community colleges and four-year institutions end up leaving without a degree. Statewide, only 26 percent of students who enroll in SUNY community colleges earn an associate's degree in three years. At CUNY community colleges, it's just 22 percent. College outcomes across New York fall far short of what our state’s employers and communities need.

Making public higher education more accessible to New Yorkers is only common sense in the emerging knowledge economy, in which the gates of upward mobility have mostly closed for young people whose education ends with a high school diploma. Opening those gates generally requires at least one year of postsecondary education or training, along with a credential that is meaningful to employers. That’s why, in January of this year, I called Governor Cuomo’s Excelsior Scholarship plan “a bold idea and a smart investment.”2 Excelsior sends an important message of college affordability to New York’s aspiring college students.

Yet Excelsior has shortcomings that threaten to cripple its effectiveness. As currently structured, this program excludes many students who need its services, puts at risk a potentially large fraction of the students who will receive its benefits, and ignores the most urgent priority of all college students: to graduate with a degree.

EXCLUSION. The Excelsior Scholarship program is effectively a gated community that excludes working students, student parents, and underprepared students – all populations that are disproportionately people of color. As a result, black and Hispanic students are likely to be sharply underrepresented in the Excelsior program.

An October 2017 press release from the governor’s office estimated that about 22,000 students will receive Excelsior benefits in the first year.3 That is in line with a SUNY projection that the total eligible pool of students is 31,300, about five percent of the undergraduate student population.4 This relatively small eligibility pool is at odds with the state’s “free college” messaging around Excelsior. But the bigger problem is how the state shrinks the eligibility pool: by excluding students whose tuition is covered by TAP and Pell, and by imposing a rigid 15-credit-hour standard that the vast majority of students cannot meet. At CUNY, for example, only 16 percent of associate’s degree students earned 30 credits in the 2015-16 school year, including remedial courses, which do not count toward Excelsior’s eligibility threshold. Even on the baccalaureate side, only 32 percent of CUNY students earned 30 credits per year.5

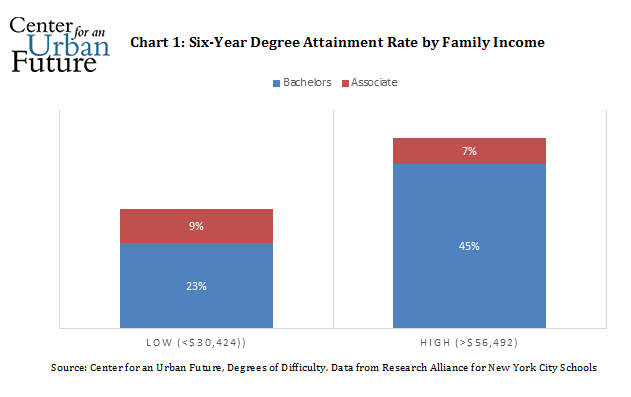

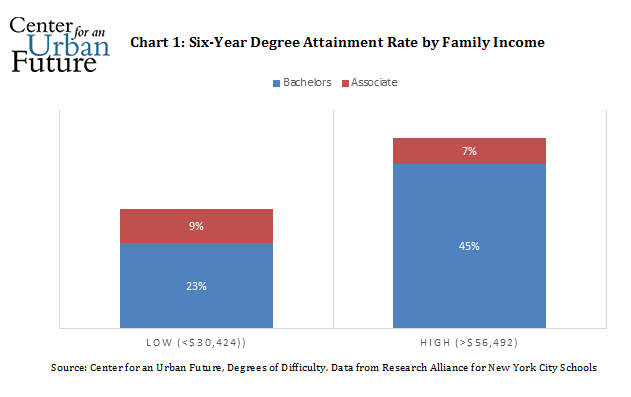

Low-income students might appear to be taken care of already, since they receive (or are at least eligible to receive) Pell and TAP grants. Yet our study found that low-income high school graduates in New York City are only half as likely to obtain a bachelor’s degree as higher-income students. See Chart Two. Financial barriers other than tuition continue to drive them out of college at staggeringly high rates. Seven out of ten CUNY community college students come from households earning less than $30,000 a year, and half of those households earn less than $20,000. Students we interviewed said over and over again that the cost of transportation to classes constantly undermined their attendance and focus. The CUNY ASAP program has doubled the three-year graduation rate among community college students in part by covering the cost of transportation and books, in addition to tuition.

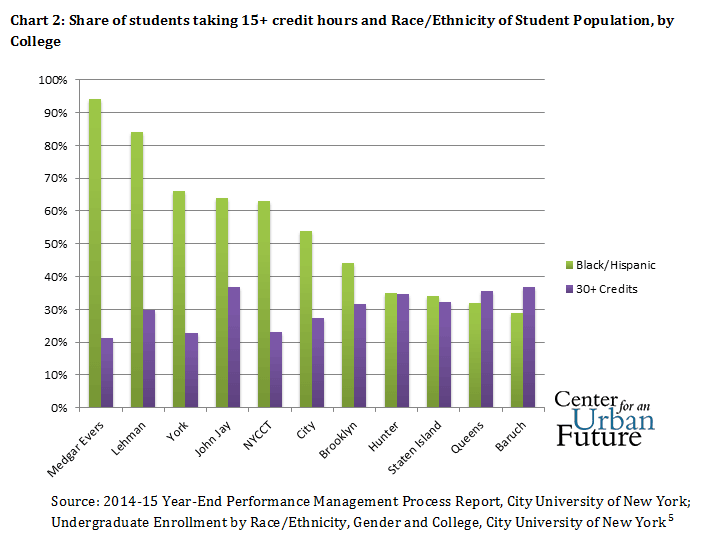

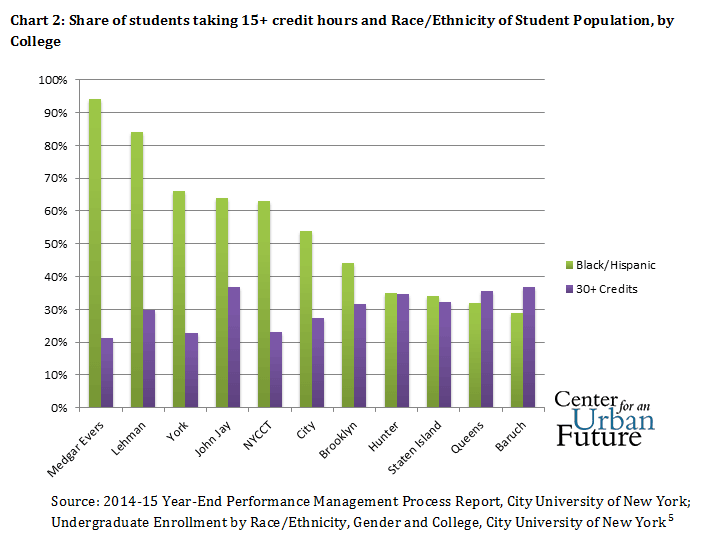

The 15-credit-hour standard is unattainable to students who work, care for children, or have to take developmental courses. At CUNY, more than half (53 percent) of community college students work while attending school, and one out of six support children financially. Those students are more likely to be disadvantaged, and in particular are more likely to be black or Hispanic. To illustrate this connection, consider the relationship between race/ethnicity and taking 15 credits or more per semester at CUNY senior colleges. The college with the lowest rate of 15+ course-taking is Medgar Evers, where 94 percent of students are black or Hispanic, while the college with the highest rate is Baruch College, where only 29 percent of students are black or Hispanic.

The difference between the lives of students at Medgar Evers and a selective senior college such as Baruch is stark. As our report shows, at Medgar Evers, 30 percent of students support children financially, compared to just six percent at Baruch. The degree of financial aid that would enable the average Medgar Evers student to take 15 credit hours each semester until graduation is likely to be far beyond anything the state legislature could ever support.

UNSTABLE BENEFITS. Students who qualify for Excelsior benefits receive a valuable financial aid grant – but an unstable one as well. Students must maintain a pace of 30 credit hours per year and remain on track for an on-time graduation or else permanently lose access to the program. The program does not pay for study in the summer or winter intersessions, thereby forcing the burden of credit accumulation on the fall and spring semesters.

Former CUNY university provost Alexandra Logue has noted several scenarios by which Excelsior scholars could lose their benefits, among them:8

- A community college student transfers to a senior college that refuses to take some of the student’s credits, a very common practice. The student loses the continuous record of on-track credit accumulation, and with it, the Excelsior benefit.

- A student is instructed to take remedial math, which does not contribute any college-level credits. The student is able to take five classes, but not six. Since the program does not cover summer or winter intersessions, all credits must be accumulated during the fall and spring semesters. The student must therefore give up the Excelsior benefit.

- The student graduates and takes an attractive job opening across the Hudson River in Jersey City. Now the student must pay back the entire benefit as a loan within ten years.

The trap doors in the Excelsior Scholarship program are numerous, arbitrary, and potentially devastating to students and their families. They add an element of risk that has no legitimate place in a promise program.

DISCONNECTION FROM STUDENT SUCCESS. The Excelsior Scholarship program seeks to bring many more students into our public higher ed system. Yet that system has a mediocre track record of getting students to a college degree. Our report shows that at New York state’s community colleges, the six-year graduation rate of the students who entered in 2010 was 32 percent. The graduation rate at senior colleges is better, but not great: about 55 percent at CUNY and 66 percent at SUNY colleges and universities. It would be a terrible irony for state policymakers to put out a welcome mat to colleges where students have a disturbingly high chance of failure and do nothing to address this discrepancy. Tennessee took a different path, spreading an evidence-based developmental education reform program statewide even as it expanded eligibility for its college promise program.

Having set forth our three major concerns, I would like to close by questioning a basic premise of the Excelsior Scholarship: the promotion of on-time college graduation. It is important to make a distinction between reducing time to degree and ensuring on-time graduation. The former is legitimate and important, while the latter is a relic of a long-dead era in higher education, when most college students were recent high school graduates whose parents could fully support them to study full-time. Today, such so-called “traditional students” are a minority of the student population. Six out of ten college students nationwide work, one in four have children, and more than half are independent.9 Some students may change their behavior to obtain the Excelsior grant, but most will find it unrealistic or counterproductive.

The state does benefit from reducing time to degree, since it subsidizes the cost of college attendance. But the budgetary savings of reducing time to degree are modest compared to that achieved by reducing college dropout. Furthermore, Excelsior does not address most of the root causes of slow progress to degree. For example, both CUNY and SUNY view outmoded developmental education programs as a drag on student progress and have proposed plans to modernize them. Instead of supporting this effort, Excelsior disqualifies developmental education students altogether. Other strategies to reduce time to degree, most of which are described at greater length in Degrees of Difficulty, might include:

- Improving transfer articulation between and within CUNY and SUNY to reduce wasted credits;

- Covering some non-tuition costs, such as transportation, or providing micro-grants that cover emergency expenses;

- Extending financial aid to the summer term, so that students can study year-round;

- Instituting a guided pathways system to reduce confusion and poorly chosen courses;

- And increasing base aid to colleges so that they can offer more sections of required courses and enhance the quality of instruction.

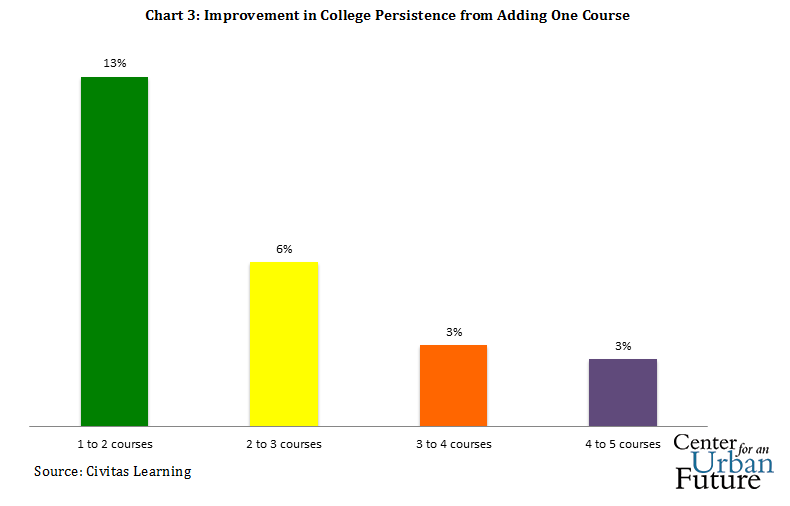

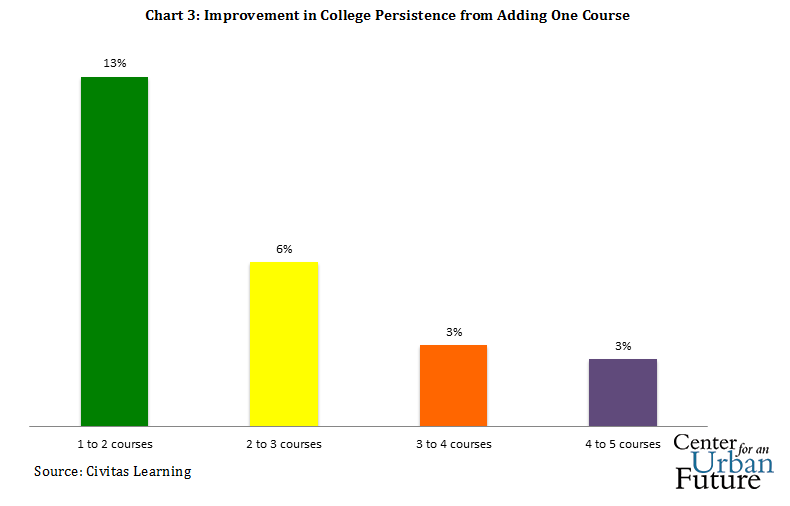

Students unquestionably benefit from taking more courses and reducing time to degree. But there’s nothing magical about taking 15 credits a semester. A more effective approach would be to encourage all students to take at least one more class and then support them. One recent study found that college persistence improves when students increase their course load, with the biggest gains at the low end.10 Students who increased their course load from one course to two experienced a 13 percentage-point gain in persistence, while those who increased their course load from four to five courses gained just under three percent. See chart 3.

I urge the State Assembly to take the following steps:

- Set measurable goals for Excelsior. The public deserves to know what Excelsior is intended to achieve, and whether it is approaching that goal. Making college affordable is a vision, but it is not a goal.

- Expand Excelsior eligibility to working learners. For example, the state could provide a certain number of credit-hours of eligibility, which students could use at their discretion.

- Explore strategies to expand benefits and supports for low-income college students.

- Establish a Student Success Fund that colleges could use to implement evidence-based initiatives to boost college completion.

I would be pleased to take any questions you may have.

1. Degrees of Difficulty is accessible at https://nycfuture.org/research/degrees-of-difficulty.

2. Tom Hilliard, “NY should make public college free-and help students graduate from it,” City Limits, January 9, 2017. Accessed from https://citylimits.org/2017/01/09/cityviews-ny-should-make-public-college-free-and-help-students-graduate-from-it/.

3. “Governor Cuomo announces approximately 53% of full-time SUNY & CUNY in-state students will go to school tuition free,” Press Release, Office of the Governor, October 1, 2017.

4. The eligibility pool will grow modestly in future years as the income ceiling rises from $100,000 to $125,000.

5. 2014-15 Year-End Performance Management Process Report, City University of New York, pp. 10 and 15.

6. Course-taking data accessed from http://www2.cuny.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/media-assets/PMP_University_Data_Book_2016_final_2016-07-29.pdf. Demographic data accessed from http://www.cuny.edu/irdatabook/rpts2_AY_current/ENRL_0033_RACE_GEN_UG_PCT.rpt.pdf.

7 Alexandra W. Logue, “Will devoting funds to Excelsior help students?” Ithaka S+R Blog, November 20, 2017. Accessed from http://www.sr.ithaka.org/blog/will-devoting-funds-to-excelsior-help-students/.

8. Demographic and enrollment characteristics of nontraditional undergraduates: 2011-12, National Center for Education Statistics, September 2015.

9. Community insights: Emerging benchmarks & student success trends from across the civitas, Volume 1, Issue 3. Civitas Learning, October 2017. Accessed from http://info.civitaslearning.com/community-insights-issue-3?hsCtaTracking=afb96daa-7349-4afc-a2a0-81f9c5f6c829%7Cf171d656-adf5-4d45-be13-5f940a0e8559.

Photo Credit: Andrew Hardy/ Flickr