The fast-growing technology sector represents one of the best opportunities for New Yorkers from low-income backgrounds to springboard into the middle class. But too many New Yorkers from low-income communities lack the required early exposure, hands-on skills, and educational credentials needed to compete for these jobs.

To create a tech sector that reflects the diversity of New York while greatly expanding access to economic opportunity, city leaders will need to set ambitious goals and commit to a bold and long-term agenda to expand and improve the tech skills-building ecosystem—starting with investments in the K–12 education system, where policymakers can have the greatest impact. What follows is a select group of high-priority solutions and a small number of additional recommendations for policymakers, agency leaders, education officials, workforce organizations, philanthropy, and the tech sector.

1. Make a significant new public investment in expanding and improving New York City’s tech education and training ecosystem. New York City has taken some vital steps toward expanding access to technology careers, including the launch of CS4AllNYC and the Tech Talent Pipeline. But as our research shows, opportunity gaps and inequities persist in the tech skills-building ecosystem—and the city still has a long way to go. New York City should make a significant new public investment to grow and strengthen the tech skills-building ecosystem, allocating funding to expand in-school computing education to every public school beginning in kindergarten; close geographic gaps by funding and scaling in-school STEM enrichment and tech workforce training programs in underserved communities; and invest in intensive, career-aligned tech training models for working adults that lead to employment in the sector. An investment of $50 million—leveraged against additional private funding—would allow the city to strengthen crucial initiatives like CS4All and the Tech Talent Pipeline, while allocating additional resources to reach more New Yorkers with computing education programs, close geographic gaps, and scale up effective adult workforce programs.

2. Set clear and ambitious goals to greatly expand the pipeline of New Yorkers into technology careers. The mayor and City Council should create a unified set of goals and benchmarks ensuring that every student has in-school access to computational thinking and computing education beginning in kindergarten by 2025; expanding in-depth tech workforce training programs to reach at least 5,000 low-income New Yorkers annually by 2025, up from just a few hundred today; and, along with New York State, tripling the number of CUNY students who earn postsecondary STEM degrees and credentials each year by 2030.

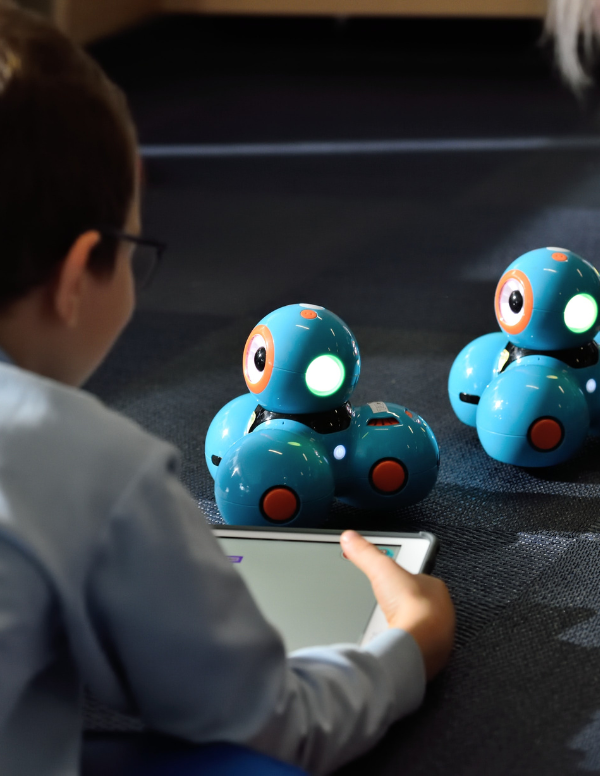

3. Prioritize long-term investments in K–12 computing education. If city leaders do just one thing to expand access and build equity in the city’s growing tech sector, our research suggests the most effective use of resources is a long-term investment in expanding and improving K–12 computing education. While New Yorkers of all ages can benefit from tech skills-building initiatives, this report finds that long-term investments in computing education are essential in order to tackle the city’s persistent opportunity gap at the root. By ensuring that every student has access to effective, age-appropriate computing education—including the core concepts of computational thinking—New York City can greatly expand the pipeline into tech careers by building skills, interests, and confidence from the earliest years of a New Yorker’s life.

- Fully fund and champion the expansion of CS4All to reach every student by 2025. The mayor and the City Council should work together to ensure that the ten-year CS4All initiative becomes a permanent pillar of the Department of Education’s strategy and meets its goal of ensuring that every student at each grade level experiences at least one unit of computing education by 2025. City leaders should ensure that CS4All has the funding and institutional support needed to achieve that goal on time, and officials should hold school and department leadership accountable for successfully integrating computing education into every school and classroom.

- Go beyond CS4All to bring computational thinking into every classroom. The mayor, the schools chancellor, and local elected officials should build on the foundation of CS4All and further grow the city’s approach to computing education. To complement the expansion of computer science classes, the Department of Education should integrate computational thinking into other topics and classrooms, including English, social studies, art, and science. In doing so, students will gain familiarity with and fluency in computational thinking concepts and processes in ways that can better prepare students for college and careers—whether they ultimately pursue computer science, technology, creative industries, the humanities, or nearly any other field.

- Significantly expand computing education in grades K–5. Today, the majority of the city’s K–12 tech skills-building programs are targeted toward high schools and middle schools, with too few programs reaching New Yorkers at the youngest ages. This lack of early exposure contributes to the alarming underrepresentation of Black and Latinx students and women in elective STEM programs and college majors, with consequences that can last a lifetime. To bring computational thinking and exploration of digital tools and technology to every grade and school, policymakers should focus on closing gaps in the K–5 system. The city should make computational thinking as fundamental as critical thinking in a child’s intellectual and cognitive development and set a goal of greatly increasing persistence of underrepresented students in STEM throughout K–12 by starting from the very beginning.

- Ensure that teachers at every grade level receive professional development in computing education. Our research suggests that the most effective way to expand computing education throughout grades K–5 is to integrate it into everyday lesson plans. But in order to do so effectively, far more K–5 teachers will need access to professional development, training, and support. The city should commit new funding to ensure that far more K–12 teachers—especially those in K–5—are accessing professional development for computational thinking and STEM learning. This investment should include funding for a full-time professional development coordinator at the DOE focused on computing education, and fund the expansion of current professional development and coaching programs like Cornell Tech’s Teachers in Residence initiative to dozens of new schools.

- Launch clear statewide standards for teacher certification and require a recognized credential in computing education for all new teachers by 2025. New York State is in the process of developing a certification for computer science teachers, but the release of guidelines has been delayed. New York State should ensure that clear guidelines for teacher certification are developed and disseminated before the end of the 2019 school year, and include clear mechanisms for educators to receive credit for prior professional development so that ongoing investments will count toward future certification. In addition, New York State is adopting new standards for computer science education beginning in December 2019, but city schools will need a larger and more consistent pipeline of trained educators to meet them. To support the development of this pipeline, the Department of Education should require a recognized credential in computing education for all new teachers by 2025—the last year of the current CS4All initiative. This requirement could help spark expanded pre-service training for aspiring teachers and create a market for designing and delivering these credentials.

4. Scale up tech training with a focus on programs that develop in-depth, career-ready skills. Although prioritizing K–12 computing education will have the greatest long-term impact on expanding access to technology careers, New York City also needs to make significant near-term investments to ensure that more working adults can train for opportunities that exist today. Seizing these opportunities will require new investments to double or triple the capacity of the specific type of programs that are in short supply today: multi-week, in-depth training programs focused on applied technical skills and real-world career readiness—and informed by specific employer needs—that consistently lead to employment, retention, wage gains, and career advancement. Today, New York City is home to a wide variety of workforce development programs and other skills-building initiatives focused on basic computer and technical skills. But relatively few free and low-cost adult training programs are focused on career-ready tech skills, and the programs that do are serving from a few dozen to a few hundred New Yorkers each year. To help more working adults access opportunities in the tech sector, policymakers should focus on scaling up the relatively small number of intensive, in-depth tech training programs that consistently lead to employment in technical occupations and provide opportunities for career advancement. Close the geographic gaps in tech education and skills-building programs. Although New York City’s tech skills-building ecosystem is larger than ever, serious geographic gaps exist across the city. It’s understandable that a large concentration of programs exists in Manhattan, for reasons including proximity to employers and accessibility across multiple transit lines. But for both K–12 and adult workforce programs to reach more low-income New Yorkers, more needs to be done to place programs in communities with few, if any, options for tech skills-building today. Efforts could include grants for existing organizations to create new program locations in underserved locations and co-location of programs in community-based infrastructure like libraries and schools.

5. Build the pipeline of educators and facilitators serving both K–12 and career readiness efforts. For both K–12 schools and tech skills-building organizations focused on serving working adults, finding and developing skilled instructors poses a growing challenge. Although greatly expanding access to professional development training is one important way to stem this shortage, our research finds that the overall pipeline of trained educators is simply too small to meet the growing demand. To strengthen this pipeline, the city should fund and launch a citywide pre-service training collaborative for computing education, in partnership with local colleges and institutions. This initiative should support pre-service training to help aspiring K–12 teachers build the skills needed to integrate computational thinking into core subjects. To strengthen the instructor pipeline for workforce training programs, the Department of Small Business Services and/or the city’s Economic Development Corporation should launch a training grant for technical facilitators designed to help in-depth workforce skillsbuilding organizations prepare recent graduates and current staff to become instructors.

6. Close the geographic gaps in tech education and skills-building programs. Although New York City’s tech skills-building ecosystem is larger than ever, serious geographic gaps exist across the city. It’s understandable that a large concentration of programs exists in Manhattan, for reasons including proximity to employers and accessibility across multiple transit lines. But for both K–12 and adult workforce programs to reach more lowincome New Yorkers, more needs to be done to place programs in communities with few, if any, options for tech skills-building today. Efforts could include grants for existing organizations to create new program locations in underserved locations and co-location of programs in community-based infrastructure like libraries and schools.

7. New York City’s tech sector should play a larger role in developing, recruiting, and retaining diverse talent. New York City’s growing tech sector is looking for ways to get involved in the broader skills-building ecosystem but lacks clear guidance around effective opportunities to help build and strengthen pathways for underrepresented talent. New York City’s tech companies can make progress on multiple fronts: reworking hiring practices to move away from college degree requirements and toward portfolio and competency-based hiring; recruiting actively from CUNY while building relationships with college leadership and career counseling offices; expanding internship and mentorship programs in partnership with local public schools, colleges, and community-based organizations; and partnering with training organizations to inform curricula while committing to hiring their graduates. In addition, the city’s tech leaders should work with existing intermediaries to develop shared infrastructure that can help small and mid-sized tech companies launch and expand internship, mentorship, and apprenticeship programs in partnership with other employers.

8. Increase access to tech apprenticeships and paid STEM internships through industry partnerships, CS4All, and the city’s current Summer Youth Employment Program. Many organizations that provide STEM skills-building programs to underserved youth report that their participants are unable to find paid internship or work-based learning opportunities in STEM fields. The result is that too many young adults from low-income communities end up choosing paid work in industries like retail or food service over unpaid internships in STEM-driven occupations. The city should support the expansion of new apprenticeship programs in tech occupations, including youth apprenticeships; work with existing industry partnerships and sector-based organizations to coordinate paid internships in STEM fields; invest in CS4All to scale from 100 to 1,000 paid internships each year; and set a goal of greatly increasing the number of STEM-related jobs available through the Summer Youth Employment Program.

9. Expand efforts to market STEM programs to underrepresented students and their families. Much of the high-quality STEM programming available to young New Yorkers today is offered on a voluntary, elective, or extracurricular basis, which means that students with a preexisting interest and confidence in STEM—as well as families with more resources—tend to benefit the most, while many underrepresented students and their families just don’t see STEM enrichment programs and tech careers as a viable, affordable, or welcoming option. To address this issue, the Mayor’s Office should launch a multi-year campaign to raise the visibility of underrepresented people in STEM fields and market STEM programs of all kinds to both parents and children, with a focus on lower-income communities. Associated activities could include family-friendly demo days featuring women entrepreneurs and entrepreneurs of color; STEM career exploration initiatives focused on the middle-school level; intergenerational programming aimed at both parents and their children; and program outreach through public libraries, cultural institutions, parks, NYCHA developments, and other community hubs.

10. Develop and fund links from the numerous computer literacy and basic digital skills-building programs to the in-depth programs that can lead to employment. Although working adults have numerous options for acquiring basic computer skills and digital skills training, very few of these programs have connections across the broader skills-building ecosystem. To better leverage the ecosystem that already exists, New York City needs to incentivize and fund partnerships across the continuum of skills-building offerings, from basic computer skills to in-depth, career-oriented programs. For instance, new city RFPs should incentivize partnerships between libraries and other training providers focused on basic digital skills and entry-level, career-oriented training programs aligned with employer needs. These linkages can help ensure that New Yorkers have a logical next step in their skills-building pathway and support outreach efforts by career-focused training providers into lowincome communities.

11. Expand the number of bridge programs to provide crucial new on-ramps to further tech education and training for New Yorkers with fundamental skills needs. Today, more than 1.1 million adults in New York City lack a high school diploma, and more than 1.8 million speak English less than very well. Due to these and other skills barriers, no matter how much the city does to grow the number of high quality, career-focused tech training programs, hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers will remain unable to access them. The city should invest at least $70 million annually in bridge programs that can serve as key on-ramps into effective education and training programs for New Yorkers with lower levels of skills and formal education.

12. Develop major new supports for the non-tuition costs of adult workforce training. For many low-income New Yorkers, the cost of attending an in-depth training program—even one with free tuition—is often prohibitive. Program managers say that too many prospective participants choose not to attend or drop out due to nontuition financial barriers, like paying for the costs of transportation and childcare, or needing to work a full-time schedule just to make ends meet. In recent years, the city has launched important new programs aimed at offsetting some of these costs, including universal pre-kindergarten and expanded reduced-price MetroCards, but much more needs to be done. The city should work with community-based organizations and nonprofit training organizations to identify the key barriers to persistence and success, and launch targeted interventions designed to help offset some of these costs for New Yorkers who choose to pursue intensive, approved training programs—including childcare support for children under age three, MetroCards for participants in intensive tech training programs, and RFPs to support food and housing security assistance for organizations that provide in-depth tech training.