Frustration with New York City’s subway system has reached a tipping point. Delays are rampant, trains are seriously overcrowded, and the core components of the network—from signal systems to tracks and train cars—are breaking down at an alarming rate.

But the city’s transit system faces another crisis affecting the daily lives of millions. Subway and bus service in the four boroughs outside Manhattan has not kept pace with massive increases in the number of New Yorkers living and working there.

No part of the city’s economy has been more deeply affected by these transit gaps than the healthcare sector.

Unlike most other sectors of New York’s economy, jobs in healthcare are not concentrated in Manhattan’s central business districts. Roughly two-thirds of all healthcare jobs—65 percent—are located in the boroughs outside Manhattan. The boroughs are also where much of the industry’s meteoric growth is occurring. Over the past decade, healthcare jobs increased by 55 percent in Brooklyn, 39 percent in Queens, 18 percent in the Bronx, and 10 percent on Staten Island. The sector grew by 15 percent in Manhattan.

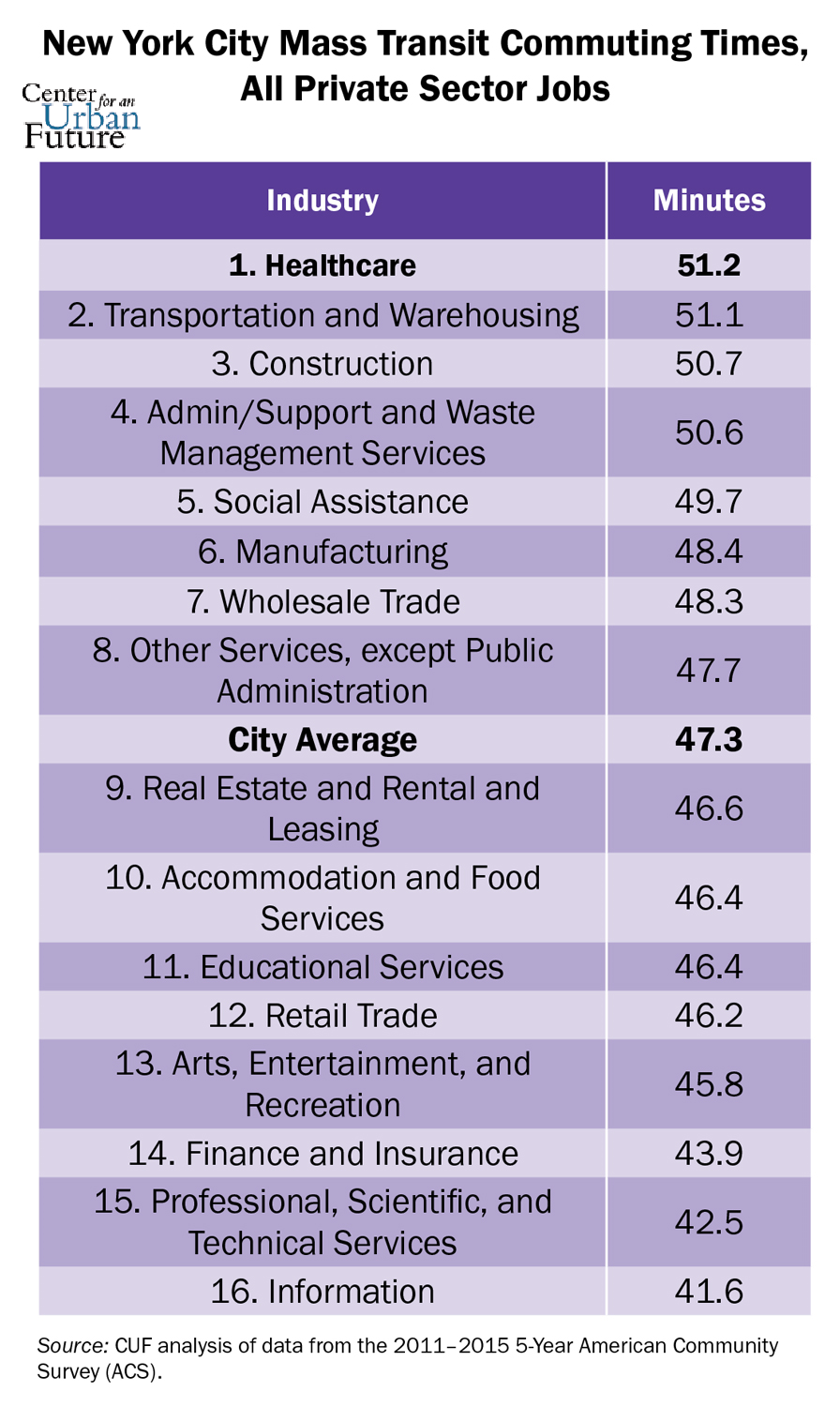

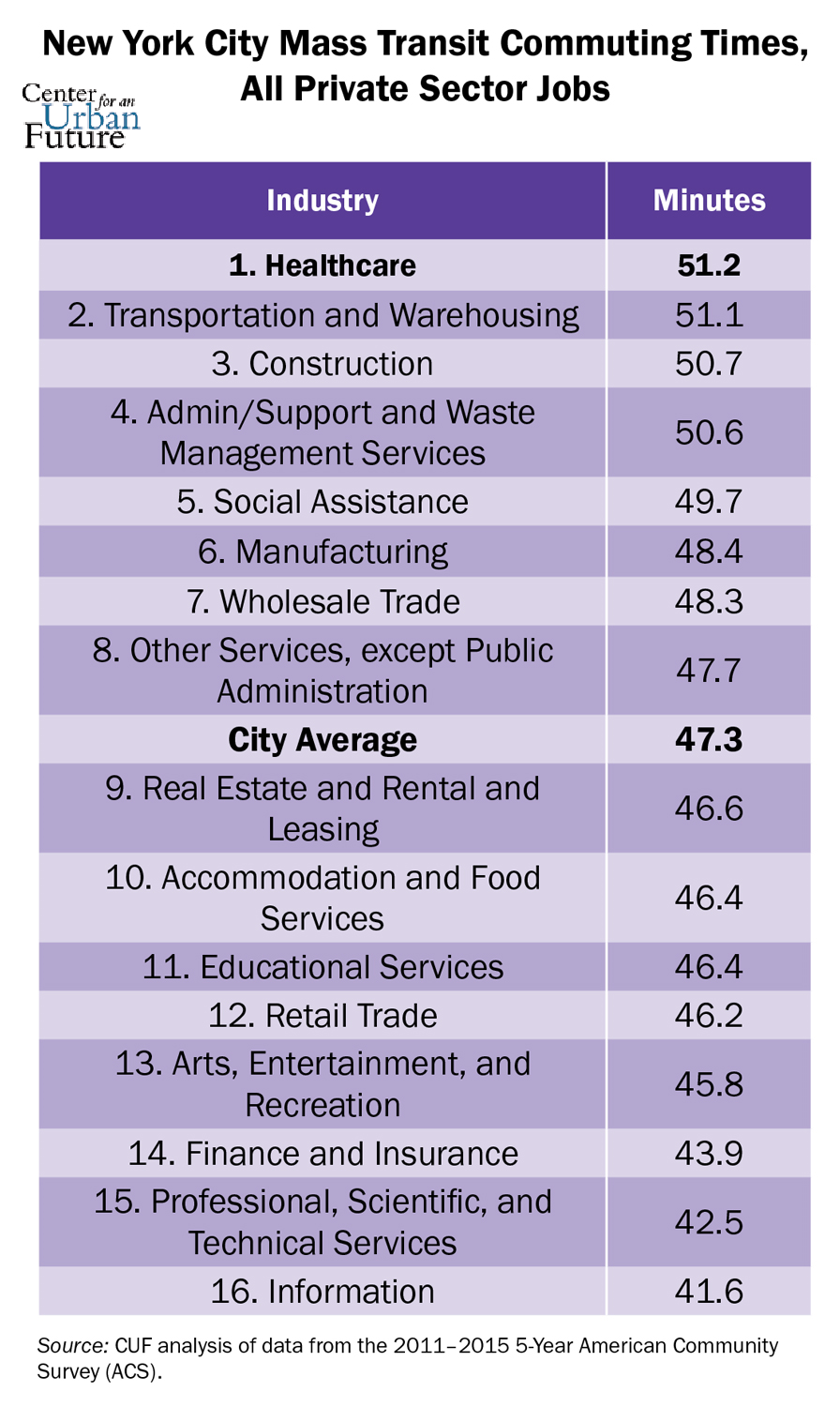

Hospitals, urgent care centers, nursing homes, and doctors’ offices are spread across the five boroughs, with many of the sector’s largest employers located in areas with severely limited transit options. The result is that healthcare workers today experience some of the worst commutes in the city. Healthcare employees who rely on mass transit face a median commute of 51.2 minutes—the longest travel time of any workers in the private sector. For healthcare workers living in Queens, the median commute is 56 minutes.1

Commutes for workers in the healthcare sector have also been increasing faster than those of any other industry. Between 1990 and 2015, the average healthcare worker’s commute increased by almost eight minutes, compared to a three-minute increase for all workers in the city. During this period, the commutes of finance workers actually decreased by three minutes.2

Although many straphangers face long commutes, those who work in the city’s healthcare sector experience unique challenges. Not only is healthcare a 24/7 business, it is one in which workers are required to be on time, alert, and enthusiastic—qualities that are necessary for providing life-saving services, but that are difficult to sustain when transit shortcomings take a grinding toll multiple times per day.

This report identifies the many specific transit challenges facing employers and workers in the healthcare sector and offers several practical recommendations to address these gaps. By working hand in hand with hospitals and other health providers, New York City can develop solutions befitting the city’s world-class healthcare system and ensure that this critical source of employment and opportunity can continue to grow.

This report, made possible by a grant from TransitCenter, provides the first comprehensive study of the transportation challenges facing the nearly half-million health workers in New York City. It draws on extensive analysis of demographic and commuting data, as well as discussions with more than 80 hospital administrators, home health care executives, union officials, community leaders, transit experts, and front-line healthcare workers serving hospitals, urgent care centers, and home health agencies across all five boroughs.

It’s not just the well-publicized subway delays and derailments that cause problems for workers in the health industry. It’s that the century-old radial design of the public transit system—intended to get workers in and out of Manhattan—is not equipped to carry essential health workers to the patients they need to serve in all corners of the city. Layer on slow buses, inconvenient scheduling, and rising fares, and healthcare workers end up with a difficult commute that is getting more challenging by the day.

It’s a situation that’s unacceptable and unsustainable, health experts say. “It’s not as though our five boroughs are rural America, but for some workers they might as well be,” says Barbara Glickstein, a public health nurse and co-director of the Center for Health Policy and Media Engagement at George Washington University School of Nursing. Glickstein is a born-and-bred New Yorker who lives in SoHo and is a major user of public transportation. “The inability of the healthcare workforce to get to work is a disruption to them and to those they are serving. It has a ripple effect.”

And when the commute is a struggle, patients suffer, say many healthcare administrators. “An employee has to be able to come to work rested and feeling good,” says Stacy Coleman, former vice president of employee performance management for Mount Sinai Health System. “When transportation in New York City leaves an employee tired and frustrated, the result is someone who’s going to have a much harder time being engaged in work throughout the day.”

Transit gaps abound in the healthcare system. Of the 105 hospitals and major medical centers we identified across New York City, at least 21 are more than eight blocks from a subway stop, as are 39 percent of the city’s 173 major nursing homes and long-term care facilities. Altogether, 32 percent of the major healthcare employers we documented in this study are more than eight blocks from a subway stop, representing the workplaces for tens of thousands of employees.

NYC's Major Healthcare Employers

But even for those healthcare employers in the boroughs outside Manhattan that are near a subway station, many still experience daunting transportation challenges. That’s because a significant share of the workers commuting to hospitals, urgent care centers, and other healthcare employment hubs live in neighborhoods that require intraborough commutes between neighborhoods that aren’t connected by a single subway or bus line.

For instance, Interfaith Medical Center in Bedford-Stuyvesant is only a short walk from the A and C trains. But Francesca Tinti, senior vice president for human resources at Interfaith, says that while a majority of the hospital’s employees live in Brooklyn, most reside in more affordable neighborhoods south of the hospital that aren’t on the same subway line. According to Tinti, of the hospital’s 1,400 employees, 119 live in Canarsie and 69 live in Flatlands. For those workers—and many more in similar predicaments—commutes to the hospital typically require two bus rides or one lengthy bus ride and a considerable walk.

In the Bronx, many major hospitals are served by the subway. But since most of the subways in the borough run north to south, workers that need to commute across the borough are left with significantly fewer transit options. We found a similar mismatch in Brooklyn and Queens, with consequences for thousands of healthcare commuters.

Our analysis of census data reveals that a significant number of the city’s healthcare workers live in neighborhoods on the city’s periphery that aren’t well served by subways. For instance, four of the New York City census districts with the highest number of resident healthcare workers—two in Brooklyn and two in Queens—are largely lacking in reliable rapid public transportation options. The 11,235 healthcare workers who commute from Queens Village, Cambria Heights, and Rosedale do not have a single subway station in their neighborhood. The 17,721 healthcare workers who live in Canarsie and Flatlands have just one station at the very northern tip of their district’s geographic boundary—too far for most residents.

As a result of these transit shortcomings, many of the city’s healthcare workers drive to work. Indeed, one Staten Island hospital administrator we interviewed estimates that 75 percent of their workers drive a car to work because transit options within the borough are so limited.

But for tens of thousands of healthcare workers in lower-wage jobs that either can’t afford a car or can’t afford the cost of parking, taking a bus to and from work is the only viable option. And for a large share of those commuters, the city’s bus network is wholly inadequate.

Many of the healthcare workers we interviewed report having to take two or more buses to work, with connections that sometimes take 15 minutes or longer as the line of waiting passengers grows. Several workers cited the particular frustrations of waiting for a poorly timed transfer or watching packed buses arrive and then depart, unable to squeeze any more passengers on board. “The bus is so packed most of the time when it gets to us that you can’t get on,” says Betty, an administrator at New York–Presbyterian/Queens, in southern Flushing, who asked to be identified by her first name only. “You fight every morning.”

These issues stem from the fact that too few of the city’s existing bus routes connect places where large numbers of healthcare workers live with hospitals, nursing homes, and other employment centers—and when they do, the service is insufficient to meet the demand. Numerous other workers say that buses don’t run frequently enough, especially during late night or early morning hours when shifts end for many hospital workers.

Our analysis of census data on commuting patterns reveals there are more daily bus commuters in the healthcare sector than in any other industry. Across the city, 17.3 percent of healthcare workers commute by bus, the second-highest share of any industry (18.5 percent of workers in the social assistance sector commute by bus).3 But the healthcare sector has nearly triple the number of daily bus commuters as does social assistance. In fact, more workers in healthcare take the bus to work every day (80,706) than do all retail and food service workers combined (78,291).

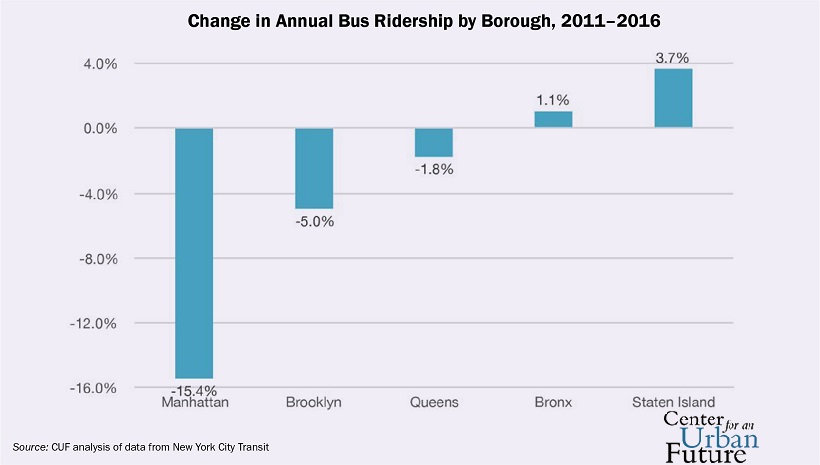

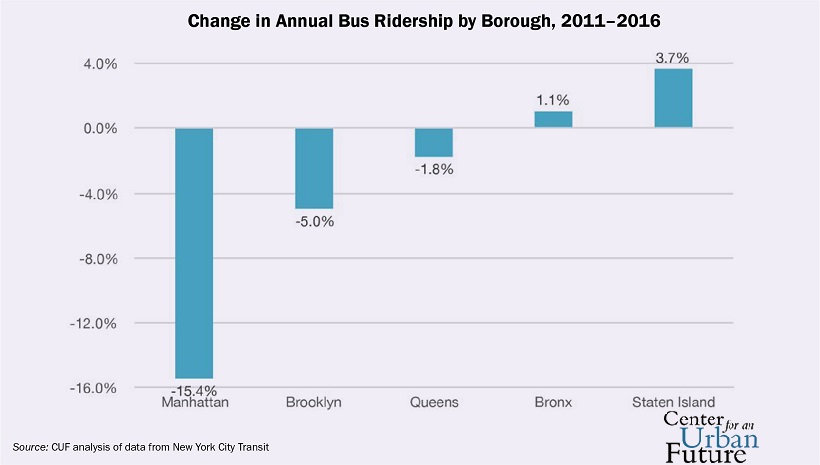

Indeed, while bus ridership has declined in Manhattan, it has increased significantly in many of the communities where healthcare employers are growing. In Brooklyn, four of the five fastest-growing bus routes provide service to major healthcare providers. For instance, ridership on the B4—which serves many healthcare workers and employers in south Brooklyn— grew 39 percent between 2011 and 2016. Bus routes in Queens and the Bronx have experienced double- and triple-digit growth in areas where they serve a number of large healthcare employers.4 In fact, while bus ridership has plunged more than 15 percent in Manhattan since 2011, ridership is up 1 percent in the Bronx and nearly 4 percent on Staten Island.

Many of these bus routes are experiencing ridership increases in part because the healthcare sector has been expanding. But another factor is that the subway system was originally built to take people in and out of Manhattan. It’s clear, particularly in the healthcare sector, that commuters need much more than that now.

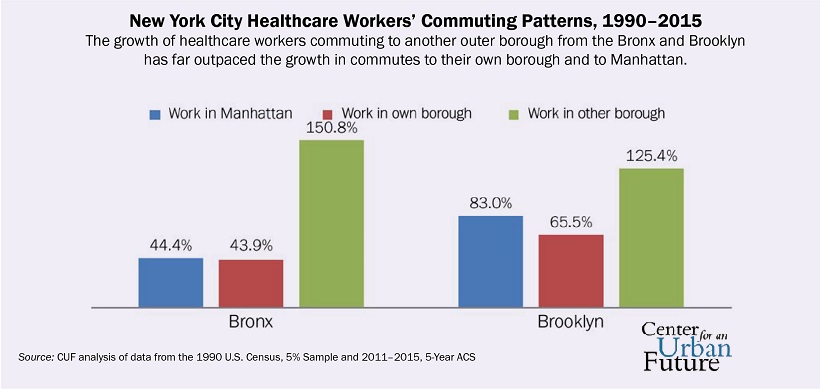

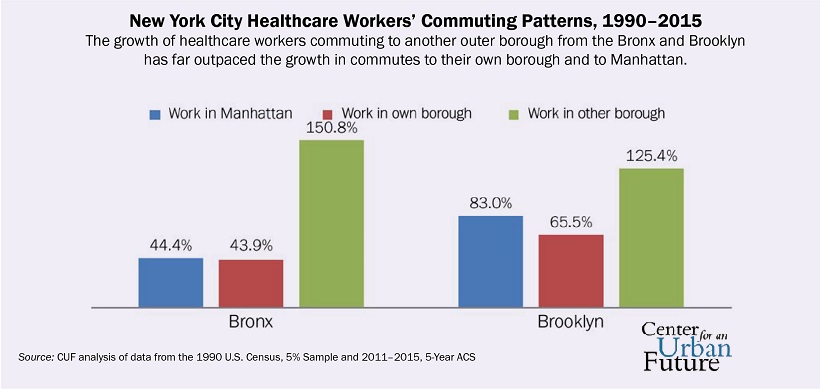

The number of healthcare workers who are both living in the Bronx and working there, for example, has risen 44 percent since 1990, while the volume of commuters from the Bronx to other outer boroughs has skyrocketed 151 percent. In Brooklyn, the number of healthcare workers staying in that borough for work has increased more than 65 percent in that time, while the number of people who live there but work in a different outer borough has risen 125 percent.5

Where NYC's Healthcare Workers Live

Although many healthcare workers struggle with long commutes, home health aides arguably have it the worst. Home healthcare is the fastest-growing segment of the city’s healthcare industry, with the number of employees increasing by a staggering 146 percent over the past decade—from 61,700 workers in October 2007 to 151,700 in October 2017. But with the average home health aide earning less than $25,000 annually, most live in working-class neighborhoods in Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx, far from the homes of their more well-heeled patients.6

For home health aides commuting to any of the five boroughs by mass transit, the average time spent commuting is 53 minutes—five minutes longer than the city’s average transit commute. Aides in the Bronx, Queens, and Staten Island have it even tougher, traveling over 57 minutes on average to get to work.

“If I have a home health aide who lives in the Bronx and a client who lives in Riverdale, it’s hell getting the aide over there,” says Carla Holub, vice president and co-owner of SelectCare Home Care Services. Holub first moved to New York in the 1980s to start a home-care agency, and since then, she says, it has become increasingly difficult to get workers where they need to go, particularly as the demand for health services expands outside Manhattan. “You either have to take a bus, or if you take the subway, you have to go back down into Manhattan and cross over and take it back uptown. It is very difficult.”

The city’s Department of Transportation (DOT) and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) have taken some steps to ease the commute in a handful of neighborhoods. In recent years, the agencies have made improvements to the bus system, expanding Select Bus Service (SBS) express routes to a total of 15 corridors over the past decade, although this falls short of DOT’s plan to operate 20 routes by the end of 2017. Today, nearly half of the system’s SBS routes are in Manhattan, despite greater demand from commuters in the other boroughs.

To its great credit, the administration of Mayor Bill de Blasio has allocated $270 million to fund Select Bus Service and announced a further expansion of SBS along 21 new routes over the next decade, most of which will be in the boroughs outside Manhattan. Meanwhile, the long-awaited opening of the Second Avenue subway extension in January 2017 improved subway access to the neighborhood often referred to as “Bedpan Alley,” home to several major hospitals, including Memorial Sloan-Kettering and New York–Presbyterian.

For more than a year, DOT has been conducting a series of public workshops to gather information about how transit can be improved across the five boroughs. Part of DOT’s ongoing Citywide Transit Plan, the process is aimed at providing reliable rapid transit to all New Yorkers regardless of their socioeconomic background.7 Also in 2017, the MTA rolled out an extensive plan to improve the bus system in Staten Island, with the goal of speeding commutes for workers traveling across the island and to other boroughs.8

But these changes have done little to ease the pain of commuting for healthcare workers. There are still limited transit options for people who need to commute from one of the boroughs outside Manhattan to another—an increasingly common demand in healthcare. That fundamental shortcoming, coupled with the ever-increasing frequency of delays and breakdowns, is causing monumental frustrations for workers in this growing sector.

Jenny Tsang-Quinn, chief of clinical programs and network development at Maimonides Medical Center, for example, needs a bus and three subways to get from her home in Kew Gardens Hills to her off-campus office in Sunset Park. When everything is working, that trip takes at least an hour and a half each way, she says. But frequent delays make that commute highly unreliable. Cascading transit problems can pose real threats to healthcare providers and timeliness, she says, with consequences for the entire organization.

“One rainy morning, maybe two years ago, for whatever crazy reason, it was like the entire staff who lived in Queens was late,” says Tsang-Quinn. “Our patients were also running late. Their aides couldn’t get them to the site on time. We had to reschedule appointments. It was just a mess. This is just one example of what happens when the weather isn’t perfect. We have staff and patients coming from Flatlands, from Canarsie, from Central Brooklyn. Some have to go north and south to reach us—there’s no diagonal transportation. Others have long bus rides as the subway line in Flatlands doesn’t travel through Borough Park. Transit is a huge problem in Brooklyn.”

When it comes to investing in transit across the boroughs outside of Manhattan, New York City has come up short. Although commuting patterns have been shifting away from the city’s outdated radial system for decades—with nearly all of the growth in population and jobs occurring outside Manhattan—the city and state have failed to tackle these transit gaps, rethink and reinvest in bus service, or analyze these issues through the lens of any specific industry, including healthcare.

When it comes to investing in transit across the boroughs outside of Manhattan, New York City has come up short. Although commuting patterns have been shifting away from the city’s outdated radial system for decades—with nearly all of the growth in population and jobs occurring outside Manhattan—the city and state have failed to tackle these transit gaps, rethink and reinvest in bus service, or analyze these issues through the lens of any specific industry, including healthcare.

To maintain New York City’s leadership role in the health industry and sustain economic opportunities across all five boroughs, the MTA and DOT must band together with local healthcare organizations to make essential changes to the transit system. This report lays out 15 achievable recommendations to find and fix transit gaps across all five boroughs and bolster transit service for the city’s critical healthcare sector.

Mayor de Blasio and Governor Cuomo need to prioritize identifying and fixing transit gaps in the boroughs outside Manhattan. This will require systematically evaluating existing transit gaps and shortcomings, providing new transit service in areas that are difficult to access today or poorly connected to major centers of employment, and upgrading the bus and subway systems to reduce overcrowding and speed up the commute.

The governor, the mayor, and the MTA should work together to make planning and investing in the bus system a top priority. This means rethinking and redesigning the bus network, which has changed little in decades; adding new SBS routes across Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx; improving speed and reliability by adopting a host of established best practices; and implementing new ideas to keep buses on schedule and close service gaps.

In addition, the city should create a healthcaretransit working group to further explore the key transit challenges affecting the healthcare system and advance potential strategies to improve access and reliability. This group should pay particular attention to the severe transit problems facing the city’s swelling ranks of home health aides, who experience some of the most painful commutes in New York.

When it comes to transit, the struggles facing healthcare workers and employers are severe but not unique. Transit gaps persist throughout the boroughs outside of Manhattan, with serious consequences for hundreds of thousands of workers in the healthcare sector and beyond. It’s time for New York to invest in the health of its transit system and improve mobility across all five boroughs for the benefit of all.

1. CUF analysis of data from the 2011–2015, 5-Year American Community Survey. This data applies to workers that both live and work within New York City.

2. 1990 data is from the 1990 U.S. Census, 5% Sample.

3. 2011–2015, 5-Year American Community Survey. The data reflects people living and working in New York City who rely on buses as their primary mode of transportation to work. Industries with fewer than 10,000 workers were omitted.

4. CUF analysis of MTA average weekday bus ridership data, available from http://web.mta.info/nyct/ facts/ridership/ridership_bus.htm.

5. CUF analysis of data from the 1990 U.S. Census, 5% Sample and 2011–2015, 5-Year ACS. Data accessed using IPUMS USA (http://usa.ipums. org). Occupation codes used to define healthcare workforce can be found in Appendix II.

6. NYS Labor Department, Occupational Employment Statistics (OES) survey, 2017.

7. NYC Department of Transportation, “New York City Department Of Transportation Launches Citywide Transit Plan Workshops Throughout the Five Boroughs,” January 2017, http://www.nyc. gov/html/dot/html/pr2017/pr17-005.shtml.

8. MTA, “New Vision for Staten Island Express Bus Service,” June 2017, http://www.mta.info/ news/2017/06/01/new-vision-staten-islandexpress-bus-service.

Photo Credit: Walter Wlodarczyk

When it comes to investing in transit across the boroughs outside of Manhattan, New York City has come up short. Although commuting patterns have been shifting away from the city’s outdated radial system for decades—with nearly all of the growth in population and jobs occurring outside Manhattan—the city and state have failed to tackle these transit gaps, rethink and reinvest in bus service, or analyze these issues through the lens of any specific industry, including healthcare.

When it comes to investing in transit across the boroughs outside of Manhattan, New York City has come up short. Although commuting patterns have been shifting away from the city’s outdated radial system for decades—with nearly all of the growth in population and jobs occurring outside Manhattan—the city and state have failed to tackle these transit gaps, rethink and reinvest in bus service, or analyze these issues through the lens of any specific industry, including healthcare.