This is an excerpt. Click here to read the full report (PDF).

Community colleges have long been the overlooked stepchildren of the educational system. But because of profound structural changes in the U.S. economy over the past several years, community colleges have become increasingly critical to the nation’s economic competitiveness and the key platform for moving low-income people into the middle class.

Since the start of the Great Recession in late 2007, young people have flocked to community colleges in record numbers. In New York City, the City University of New York’s (CUNY) two-year institutions have 43 percent more students than a decade ago. Much of the increase has occurred in the last few years, signifying that a postsecondary credential is now seen as the bare minimum for accessing decent-paying jobs.

Unfortunately, community colleges are not yet delivering on all their potential. Far too few people who enroll at community colleges, both in New York City and across the country, end up graduating or moving on to earn a bachelor’s degree. In New York City, 28 percent of community college students graduate with an associate’s or bachelor’s degree within six years of enrolling. The national average for community college graduation after six years is even lower, at 26 percent.

There are understandable reasons why graduation rates have been low. To begin with, community colleges are open access institutions, and they accept whoever applies. A significant number of the students already face steep hurdles when they enter. For instance, of those who arrive at a CUNY community college from a public high school, four out of five must take at least one remedial class. Three in ten are working more than 20 hours per week to earn a living. On top of this, community colleges receive less than half the funding per student received by four-year colleges and universities, and state funding of the CUNY community college system has dropped by more than one-quarter over the past decade.

Nevertheless, community colleges could and should be doing much better. As we show in this report, low graduation rates exact steep costs to individuals, businesses, the economy and taxpayers. Increasing the number of community college students who graduate will not only make it easier for employers to find qualified workers, it will dramatically raise the employment prospects of graduates and put them on a career track with significantly higher earning potential. And, of course, with higher earnings comes more spending in the local economy, higher tax receipts and more effective public investments in the form of operating aid and grants.

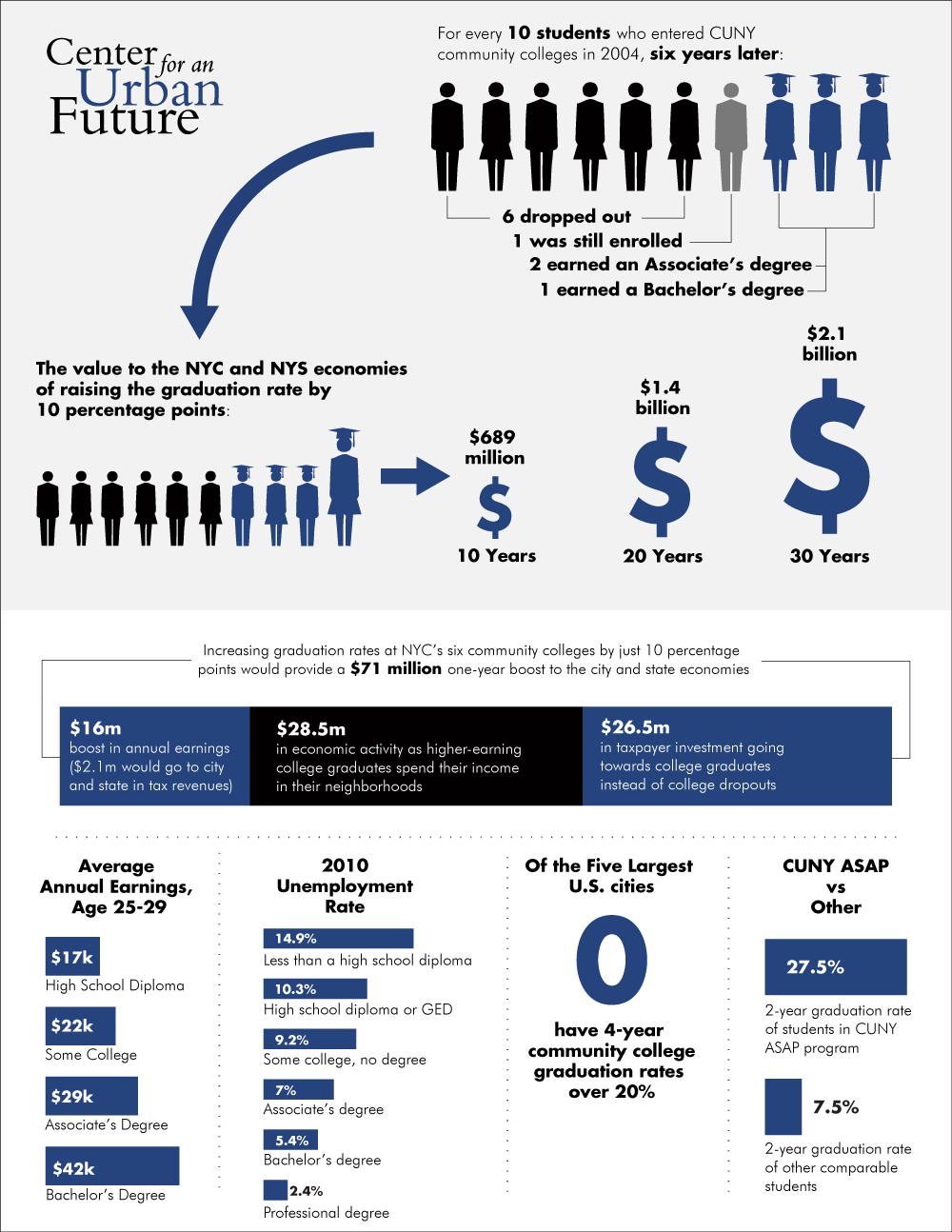

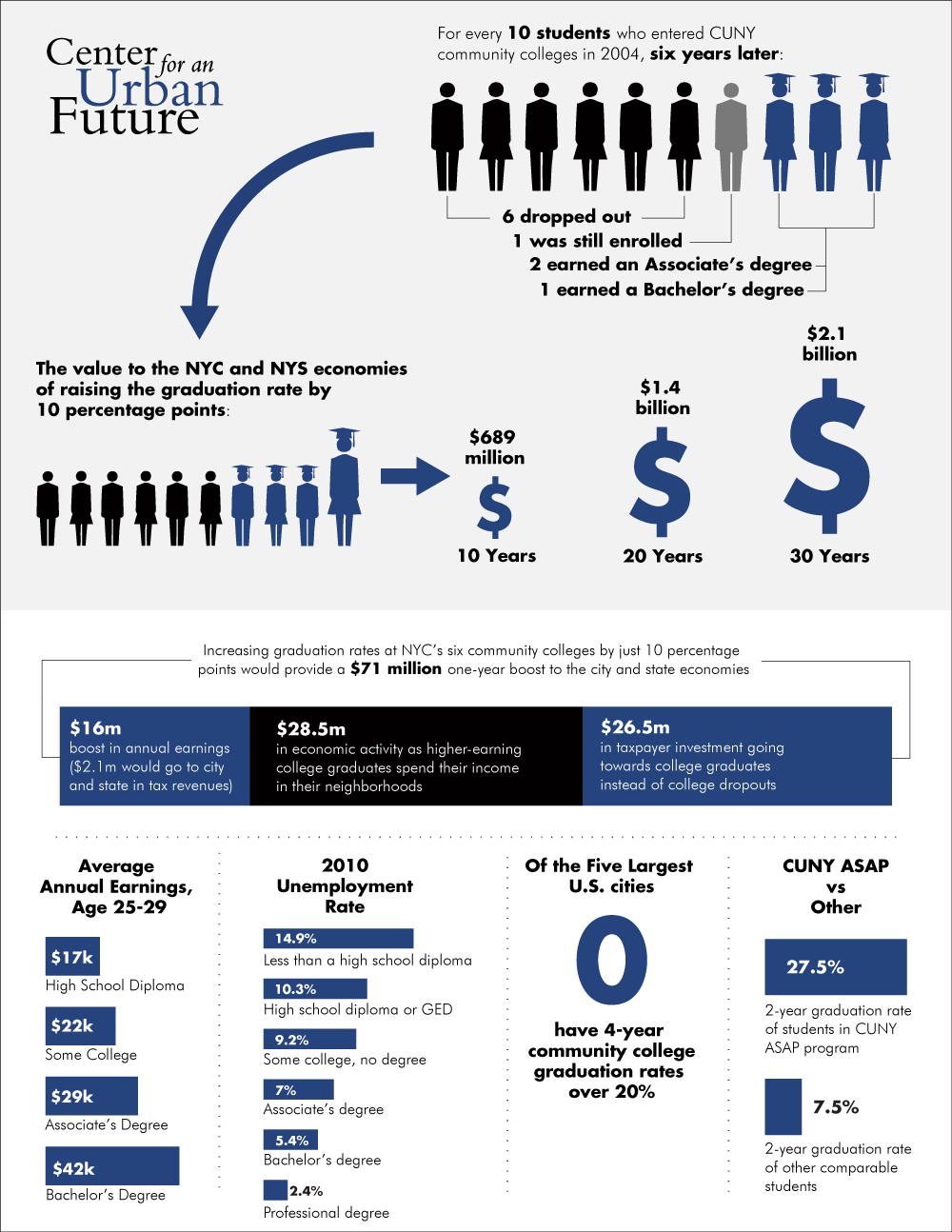

We estimate that increasing graduation rates at New York City’s six community colleges by just 10 percentage points for the class that entered in 2009 would provide a $71 million one-year boost to the city and state: a $16 million boost in annual earnings (of which $2.1 million would go to the city and state in tax revenues), $28.5 million in economic activity as higher-earning college graduates spend their income in their neighborhoods, and $26.5 million in taxpayer investment going towards college graduates instead of college dropouts. Over a decade, the combined income, economic activity and public-investment value to New York City and New York State of raising the graduation rate by 10 percentage points would be roughly $689 million; over two decades, $1.4 billion; over a three-decade career, $2.1 billion.

Increasing the graduation rate permanently would have powerful long-term value for the city’s economy.

* * *

This report aims to document why raising the rate at which individuals are graduating from community colleges in New York City—and getting more from the public’s already significant investment in community colleges—is of critical importance from a fiscal, economic and social perspective. The study, which is supported by the IBM International Foundation, details the cost of high community college drop-out rates and the return on investment that would result from raising graduation rates even by a small amount.

The abysmal rate at which individuals graduate from community colleges is a national problem, and it is particularly bad in large urban areas where a substantial share of the students enrolled are from disadvantaged backgrounds who attend poorly performing public school systems. None of the five most populous cities in the United States have higher than a 20 percent four-year graduation rate among their community colleges—Los Angeles has the highest (with a 20 percent graduation rate), followed by New York City (19 percent), Philadelphia (14 percent), Houston (14 percent) and Chicago (10 percent). (We use four-year graduation rates here because it was the only readily available data set for all major U.S. cities. Elsewhere in the study, we use six-year graduation rates, which were available for New York City and the nation and which we believe present a more accurate portrait of graduation patterns at these institutions.)

We chose to focus this report on community colleges in New York City, not because the graduation rates in New York are lower than elsewhere—on the contrary, they are higher than three of the other four largest cities in the U.S.—but because New York has the nation’s largest system of urban community colleges in the United States. The challenges and opportunities here offer a useful window on what is at stake in the fate of two-year public colleges across the country.

The six CUNY community colleges—Kingsborough, Borough of Manhattan, Queensborough, LaGuardia, Bronx and Hostos—have a collective enrollment of more than 91,000 students, of whom roughly 82,000 seek to earn an associate’s degree or to prepare for transfer to a comprehensive college for pursuit of a bachelor’s degree.

Currently, too few of these students are coming away with a degree. Of the 10,185 students who started at CUNY community colleges in 2004, a staggering 63 percent dropped out within six years, 28 percent earned a CUNY degree—20 percent received an associate’s degree and 8 percent a bachelor’s degree—and 9 percent were still enrolled.

As we show in this report, improving upon these lackluster numbers would have clear benefits for students, businesses, the broader New York economy and taxpayers.

Both nationally and in New York City, people with college credentials are much more likely to be employed than those with only a high school diploma or some college. The employment participation rate (that is, the share of employed adults) for New York City residents with an associate’s degree is 68 percent; in contrast, only about half of all city residents with a high school diploma or a year of college are employed at any given time.5 In 2010, during the peak of the Great Recession, the unemployment rate for those with an associate’s degree was just 7 percent, compared to a 14.9 percent jobless rate for those with less than a high school degree, 10.3 percent for individuals with only a high school diploma or GED and 9.2 percent for people who have completed some college (but who have not achieved an associate’s degree). New Yorkers with higher levels of educational attainment fared even better; the unemployment rate was 5.4 percent for individuals with a bachelor’s degree and 2.4 percent for those with a professional degree.

Individuals with at least an associate’s degree are also likely to earn a lot more. According to a recent study, workers with an associate’s degree earn, on average, 30 percent more over the course of their career than workers with a high school degree only, while workers with a bachelor’s degree earn over 75 percent more over the course of their career.

Our analysis of Census data finds that average annual earnings for a high school graduate in New York City, ages 25-29, are about $17,000, and a year of college without a degree will bump average income to $22,000. But an adult with an associate’s degree earns $29,000 on average. As a result, someone who attends college for a year and drops out is giving up an average of $7,000 in annual earnings by not completing their associate’s degree. Also, more than one in four CUNY community college students who graduate within six years does so with a bachelor’s degree. Even as young adults in their late 20s, they earn an average of more than $40,000 in New York City, an even greater advantage over high school graduates and those who complete only some college without getting a degree. “People sometimes ask: ‘should everybody get a college degree?’” notes Thomas Bailey, director of the Community College Research Center at Teachers College and a national expert on community college completion. “No, but it’s fairly clear that the economic returns to education over a lifetime are way above the costs.”

In addition to forgoing the additional earning power that an associate’s degree would bring, college dropouts are more likely to default on their student loans. Though the numbers are relatively low compared to private four-year or for-profit institutions, about nine percent of CUNY community college students take out federal loans, at an average of $3,000 per loan. And one out of nine defaults within three years.