The following is the introduction to Completion Day. Click here to read the full report (PDF).

As New York State transitions from a manufacturing economy to a knowledge economy, few institutions are playing a more important role than the state’s 35 community colleges.

With more than 328,000 students enrolled statewide, community colleges are boosting New York’s economic competitiveness by upgrading the skills of a large chunk of the state’s workforce. They are enabling displaced workers to acquire skills in occupations that are growing, and helping businesses across the state meet their evolving workforce needs—from photonics in Rochester to nanotech in Albany. Perhaps most importantly, community colleges have become the state’s key opportunity institutions. At a time when a high school diploma is no longer sufficient to obtain a decent paying job in most industries but the cost of getting a college education has skyrocketed, the state’s community colleges offer the most accessible path for tens of thousands of low- and moderate- income New Yorkers to obtain a post-secondary credential.

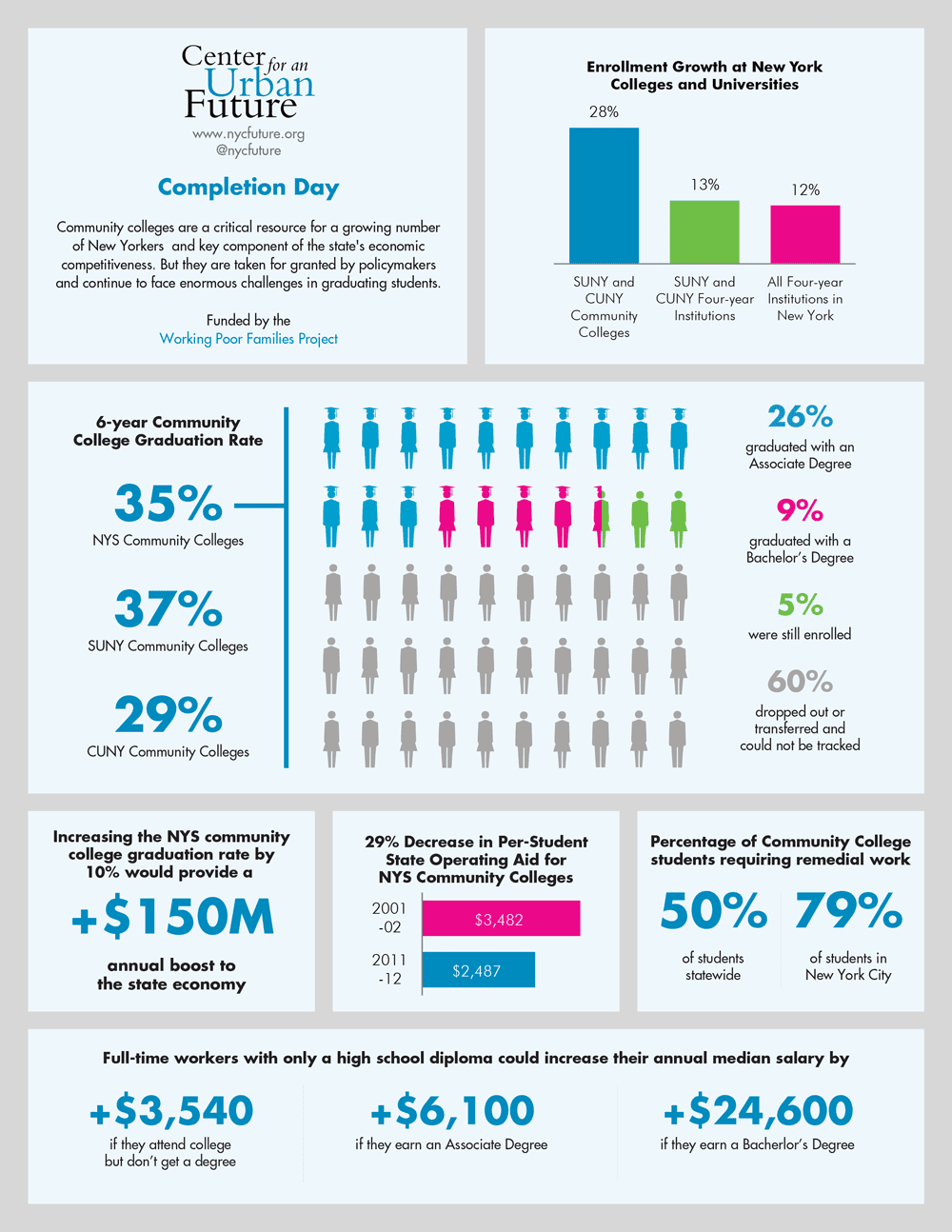

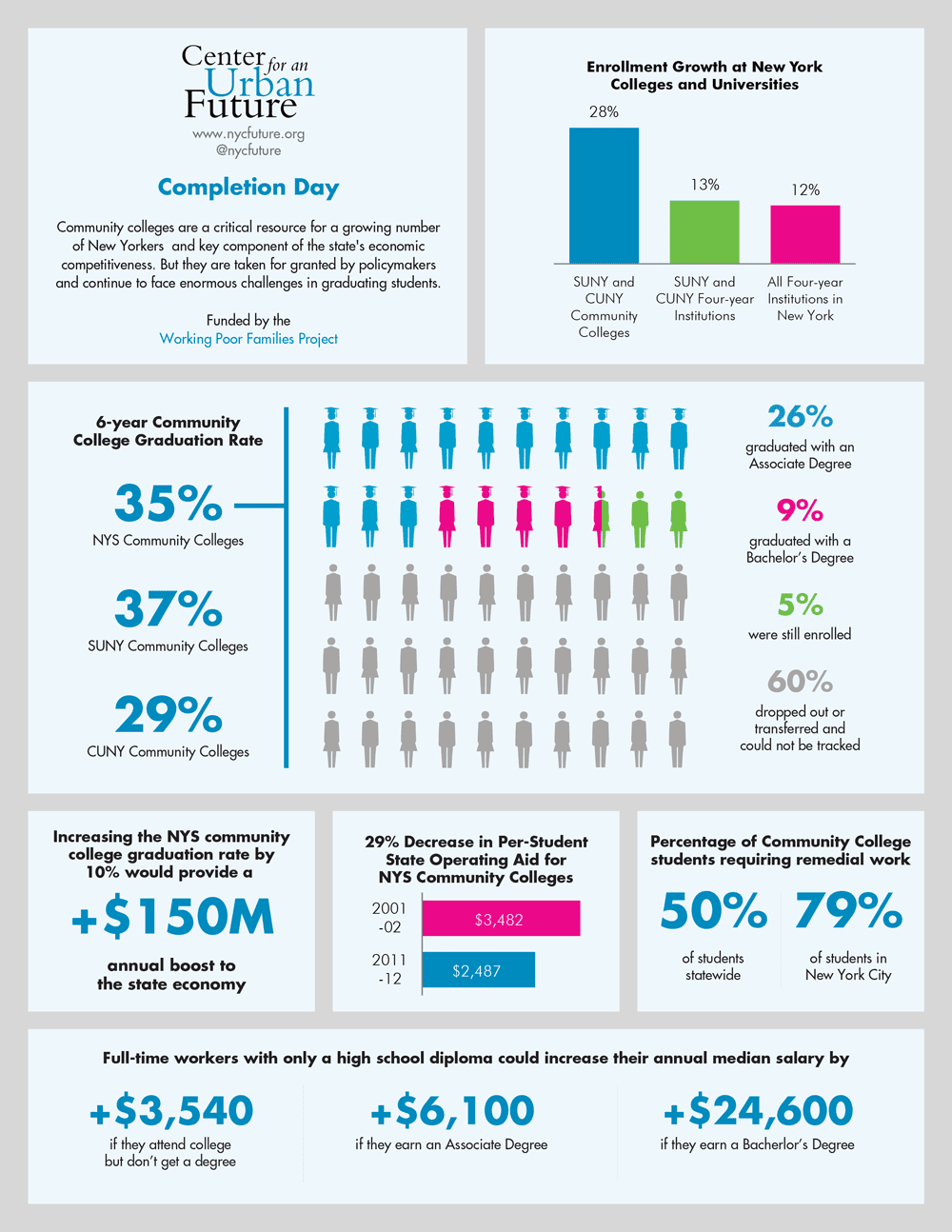

Due in large part to their importance as vocational resources in a quickly changing economy, student enrollment has been growing faster at two-year institutions than at four-year institutions in New York. Over the last decade, enrollment at State University of New York (SUNY) and City University of New York (CUNY) community colleges increased by 28 percent, compared to 13 percent at SUNY and CUNY four-year institutions and 12 percent at all four-year colleges and universities in the state.

However, the state’s community colleges have only just begun to deliver on their potential and face enormous challenges in the years ahead. Far too few students who enroll at community colleges in New York end up graduating or moving on to a four-year institution. Statewide, only 35 percent of full-time students who enroll in community college courses obtain an associate or bachelor’s degree after six years. And in New York City, where a much higher percentage of students qualify as low-income, the six-year graduation rate is just 29 percent. While some schools do better than others at graduating students, every community college in the state has a six-year graduation rate below 50 percent.

Community college students fail to graduate for a number of reasons. Although more New Yorkers are choosing to enroll in community colleges, many are unprepared for college level work. Fifty percent of students across the state—and 79 percent in New York City—need remedial work before they can begin on a more specialized career track. Moreover, even as enrollment has increased, state funding has declined by 29 percent over the last decade, leading to higher tuition costs and a larger financial burden for many students of moderate means.

Raising community college graduation rates will be an enormous challenge for both academic leaders and state policymakers, but doing so is clearly worth the investment. As we demonstrate in this report, higher graduation rates would not only provide growing industries with the workers they need to remain competitive, it would dramatically increase the earning potential of thousands of New Yorkers, leading to both increased regional GDP and government revenue. We estimate that increasing graduation rates by just 10 percentage points would provide a $150 million one-year boost to the state economy; a $41 million increase in the annual incomes of those who graduate; a $32 million increase in economic activity as those higher earning graduates spend more on goods and services; and $44 million in taxpayer investments going toward graduates rather than dropouts.

Over the next decade, the combined value of raising community college graduation rates from 35 percent to 45 percent would be $1.5 billion, over two decades $3 billion, and over three decades $4.5 billion.

This report details the increasing importance of community colleges to New York State’s economy and documents why raising graduation rates at the state’s community colleges by even a small amount would result in significant benefits to the state’s employers, young adults and the working poor. A follow-up to our 2011 Mobility Makers study, which focused on the importance of improving the graduation rate at the six community colleges in New York City, this report details graduation rates for all 35 community colleges statewide and focuses mainly on SUNY community colleges across the state. Funded by the Working Poor Families Project—a national initiative supported by the Annie E. Casey, Ford, Joyce and Kresge Foundations, which partners with nonprofit organizations to strengthen economic conditions and state policies affecting working families—the report is based on extensive data analysis and more than two dozen interviews with community college leaders, education experts and employers from nearly every region around the state.

Low graduation rates have been a chronic affliction of community colleges in New York and nationwide, stemming in part from their open access mission to accept all students regardless of test scores or high school GPA. But as the economy continues to put a premium on postsecondary credentials, even for traditionally low-tier positions, the lack of progress in raising those rates is posing larger and larger problems. The jobs that community college graduates fill are not only projected to grow significantly in the coming decade; they are in industries that are pivotal to the state’s economic future, including advanced manufacturing, technology, health care, and high-end services such as finance and law.

Many of the employment experts we spoke to during our research for this report told us that postsecondary credentials are becoming increasingly important for the vast majority of middle skill jobs. “The number of our employees who have at least an associate’s degree has grown over the past decade” says Chris Sansone, the production manager at the Keller Technology Corporation, a high-tech manufacturer in Buffalo. “Depending on the job, I expect there will be a two-year degree minimum in the next five years or so.”

Employers also value occupational certificates and industry certifications which respond directly to employer demand. Erie Community College in Buffalo developed a one-year certification program in Computer Numeric Control (CNC) to support employer needs in the region’s growing advanced manufacturing sector. According to Sansone, all of Keller Technology’s precision machinists are now required to go through the program.

“The jobs filled by community college students are very important [for our local economy],” says Mark Peterson, president and CEO of Greater Rochester Enterprise, a business group. “At least 50 percent of the new jobs in Rochester will require some type of degree beyond high school.”

Community colleges prepare residents for higher skilled jobs in the knowledge economy in a variety of ways. They offer two-year degrees and certificates in specific career skills, ranging from nursing to welding; serve as a workforce development resource by providing customized training courses for local industry; offer a low-cost starting point for people who plan to move on to a four-year college; and offer programs in high school equivalency, adult literacy and English as a second language. Community colleges are critical for working adults who need to upgrade or retool their skills. The rapid spread of technology and outsourcing has resulted in the dislocation of millions of adults across the state, and community colleges train these dislocated adults for new occupations in growing industries.

More than any other educational provider, community colleges serve the needs of their regional economies and have proven themselves adept at responding to changing economic conditions with new professional degree and certification programs. For example, Monroe Community College is the only two-year institution in the nation that offers a degree in optical systems technology and regularly places its graduates at local firms, including Xerox, Bausch and Lomb, Corning and Kodak. More recently, Hudson Valley Community College in Troy built a high-tech outpost near the new GlobalFoundries semiconductor plant in order to prepare students for the anticipated 1,400 new jobs there.

Outside of New York City, where it is harder to attract talent from other regions of the country or globe, preparing local residents for higher-skilled jobs in local industries could mean the difference between economic revival and continued decline. Businesses need to have a competitive workforce if they are going to be competitive themselves, and economic research has shown that more education can lead to an exponential rise in productivity, since the person who has acquired the extra learning and skills is not the only one who benefits—their co-workers and collaborators do as well.

“If you look at the numbers,” says Randall Wolken, president of The Manufacturers Association of Central New York (MACNY), “people just do better when they have been certified in skills, and employers feel more comfortable hiring them, even if it is at the basic skill level and they have to stack on additional skills.”

Their increase in earning power is also significant. According to the New York State Department of Labor, an individual who earns an associate degree will make an average of 18 percent more per year than someone with a high school diploma. Moreover, a significant number of community college students go on to earn a bachelor’s degree, and these individuals earn an average of 73 percent more than those with a high school diploma. Full-time workers with only a high school diploma could increase their median salary by $3,540 annually if they attend college but don’t earn a degree and by $6,100 annually if they earn an associate degree. An adult who attends college but does not complete is therefore giving up nearly $3,000 a year in additional income. These figures are actually significantly understated since they don’t take into account pay raise patterns or other incidental benefits such as increased job satisfaction and improved health.