The following is the introduction to The New Face of New York's Seniors. Click here to read the full report (PDF).

Like much of the rest of the country, New York City is graying rapidly. In the next two decades, demographers expect the number of city residents 65 and older to increase by 35 percent, going from approximately 998,000 today to 1.3 million in 2030.And while some initial steps have been taken to plan for this profound demographic shift, not nearly enough attention has been paid to a crucial—and especially vulnerable—subset of the city’s senior population: those who were born in a foreign country and continue to reside here as either documented or undocumented immigrants.

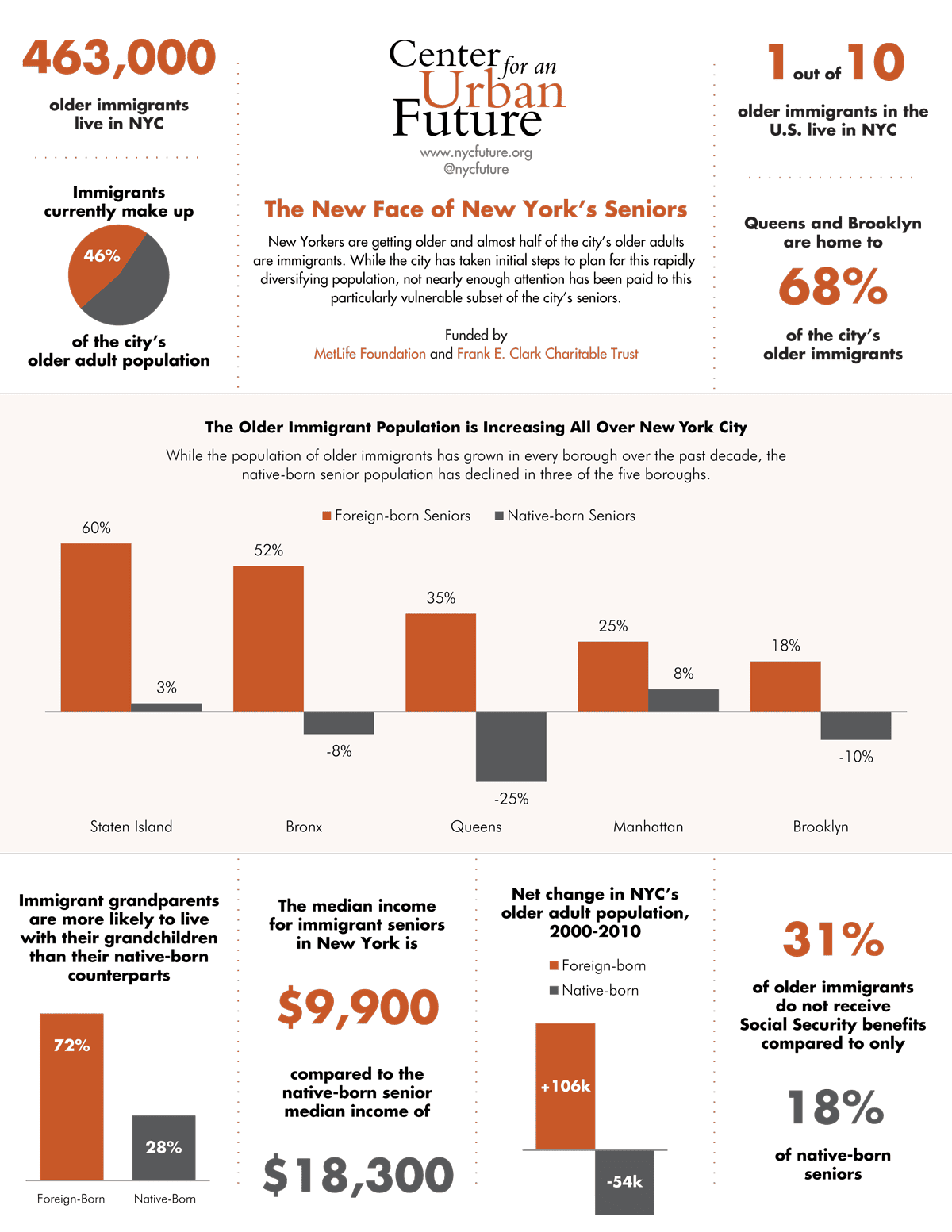

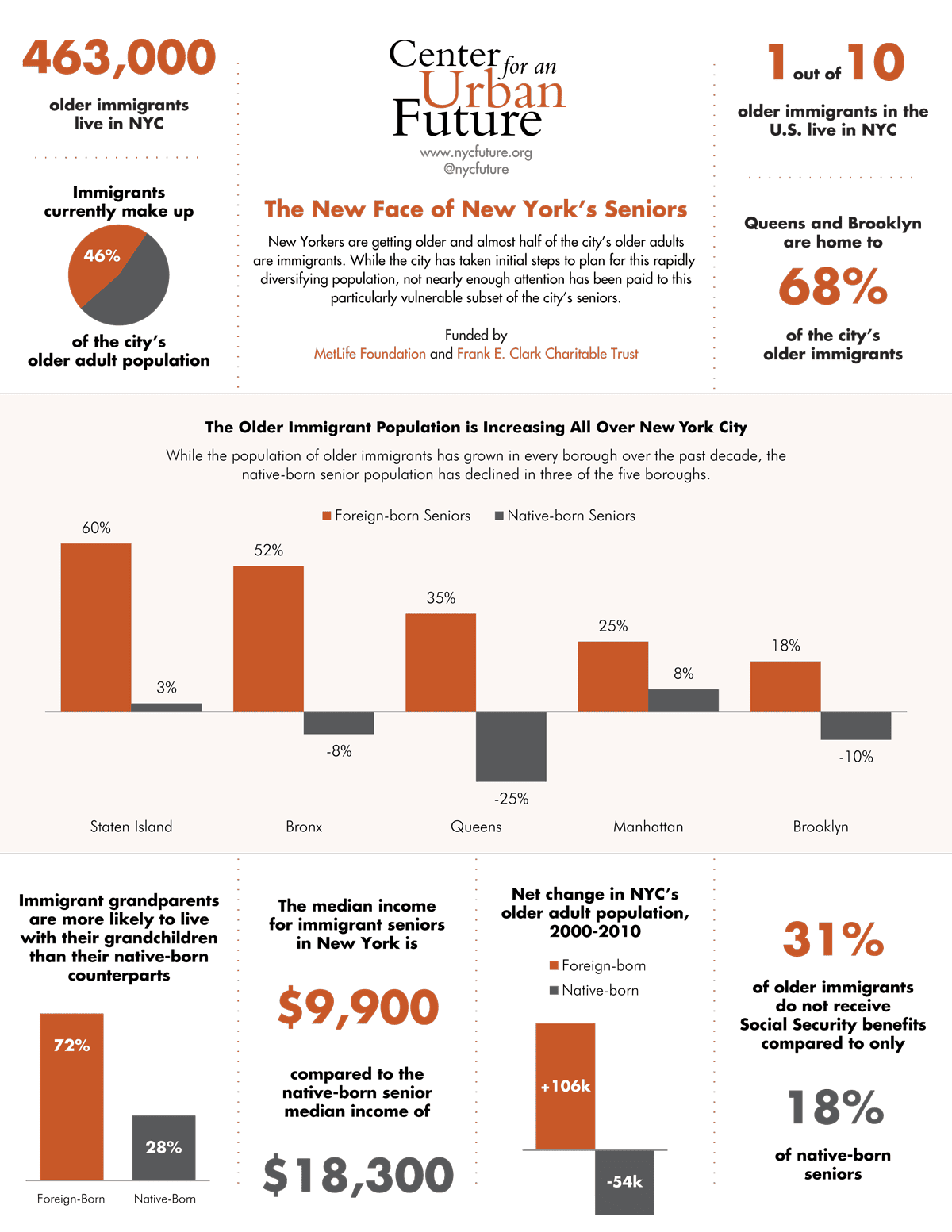

With 463,000 older immigrant residents, New York has by far the largest foreign-born senior population of any city in the U.S. In fact, one out of every ten older immigrants in the country calls New York City home. Immigrants currently make up 46 percent of the city’s total senior population, and if current growth rates continue, they will become the clear majority in as little as five years. In 21 out of the city’s 55 Census-defined neighborhoods, immigrants already account for a majority of the senior population; in Queens, this is true for ten out of 14 neighborhoods.

The aging of the city’s immigrant population has huge implications for New York. As a group, immigrant seniors have lower incomes than their native-born counterparts and much less in retirement savings. They receive far fewer benefits from traditional entitlement programs like Social Security and Medicare. Compounding these challenges, nearly two thirds of immigrant residents age 65 and older have limited English proficiency, while nearly 200,000, or 37 percent, live in linguistically isolated households. As a result of these language and cultural barriers, many older immigrants have trouble finding out about existing support services and are much more likely than their native-born counterparts to suffer from isolation, loneliness and depression.

With so many immigrant neighborhoods, one of the most comprehensive health systems in the U.S. and excellent public transportation, New York has the potential to be a great place for immigrants to grow old. But it is far from clear that the city has the infrastructure or programs to handle all the challenges that are likely to arise as this population increases. City funding for senior services has actually fallen significantly since 2009. And although the Bloomberg administration recently unveiled the widely heralded Age-Friendly NYC, an initiative created with the New York Academy of Medicine to assess how the city’s existing services affect seniors, many immigrant groups and community-based organizations say that initiative doesn’t address the particular needs of older immigrants, a major oversight in a city where they are not only one of the fastest growing demographic groups but also one of the most vulnerable.

Drawing on Census data, this report provides extensive demographic details about New York’s older immigrant population, including where they immigrated from, how long they’ve lived in New York City, which neighborhoods they live in and how many have access to government assistance, among other important factors to their well-being. In order to better understand the challenges foreign-born seniors face and how well the city is prepared to meet those challenges, we interviewed over 50 caseworkers at community-based organizations, advocates for immigrants and older adults, government officials, academics and a wide variety of policy experts in health care, community development and social services. Together, the data and first-hand accounts paint a picture of an increasingly international senior population in New York, with challenges and needs that are both common to all older New York residents and unique to their immigrant status or even their ethnicity or country of origin.

Over the next decade, both New York and the country will be profoundly affected by the rapid aging of the population. Nationwide, the Baby Boom generation that built our postwar economy and continues to form the powerbase in politics and business will put major strains on our entitlement and social safety net programs as they move out of the workforce into retirement. The first member of this generation turned 65 in 2010, and over 10,000 have been reaching this milestone every day since then. And yet, as serious as this trend is on a national scale, it is likely to pose even bigger challenges in New York, where an increasing percentage of the older generation came here from another country and culture.

“We are not paying attention to this very important demographic shift,” says Joan Mintz, director of special projects at the Lenox Hill Neighborhood House in Manhattan. “[The immigrant population is] getting older and older. We need to be planning for services for a lot of people moving forward, but we have not put dollars and brainpower and policy on these issues.”

The median age of New York’s immigrant population is 14 years higher than that of the native-born population. While the median age of an immigrant New Yorker is 43, the median age of a New Yorker born in the U.S. is 29.

The total number of older immigrants in New York is also increasing rapidly. Over the last decade, as the native-born senior population decreased by 9 percent, the number of older Asian immigrants grew 68 percent, older Caribbeans 62 percent and older Latinos 58 percent. Overall, the number of foreign-born seniors jumped 30 percent in that time, going from 356,000 in 2000 to 463,000 ten years later.

“The aging segment of the Asian population is the fastest-growing part,” notes Howard Shih, a demographer at the Asian American Federation in New York. “The wave that came in the 1960s, when the Immigration Act removed race-based quotas, has been here for over 40 years and is now getting to retirement age.”

Although Queens and Brooklyn are home to the vast majority of immigrant seniors overall (67 percent of the city’s total), every borough has seen its older immigrant population spike dramatically since the beginning of the decade. Between 2000 and 2010, the number of foreign-born seniors in Staten Island grew 60 percent, the Bronx 51 percent, Queens 36 percent, Manhattan 25 percent and Brooklyn 18 percent. Only one borough—Manhattan—saw a significant increase in native-born seniors during that time, while three boroughs—the Bronx, Brooklyn and Queens—saw significant decreases. In all, 21 out of 55 neighborhoods in New York experienced at least 50 percent growth in their immigrant senior population, including six neighborhoods in Queens, five in the Bronx, four in Brooklyn, and three each in Manhattan and Staten Island.

Some of the neighborhoods that have seen tremendous growth in the number of older immigrants are in areas with well-established immigrant communities, such as Flushing in Queens, Chinatown in Manhattan and Sunset Park in Brooklyn. But, somewhat surprisingly, many other high-growth neighborhoods are not traditional immigrant enclaves and, in a few cases, have relatively few existing services or age- and immigrant-friendly amenities. These include Mott Haven/Hunts Point in the Bronx (with 181 percent growth since 2000), Far Rockaway in Queens (with 83 percent growth) and the North Shore of Staten Island (with 50 percent growth).

Because immigrant seniors tend to be poorer and have much less in retirement savings than their native-born counterparts, and because they tend to have a much harder time accessing existing support services and programs, many in this group are not only poised to strain the social safety net but fall through it entirely.

The median income for immigrant seniors in New York is $8,000 lower per year than for native-born seniors ($9,900 compared to $18,300). And for those living in households of two or more people, this disparity grows to nearly $40,000 per year ($52,185 compared to $90,800). Nearly 130,000 immigrant seniors in the city, or 24 percent of the total, are living in poverty, compared to 69,000 or 15 percent of native-born seniors. Older immigrants comprise 46 percent of all seniors in New York, but 65 percent of all seniors living in poverty.

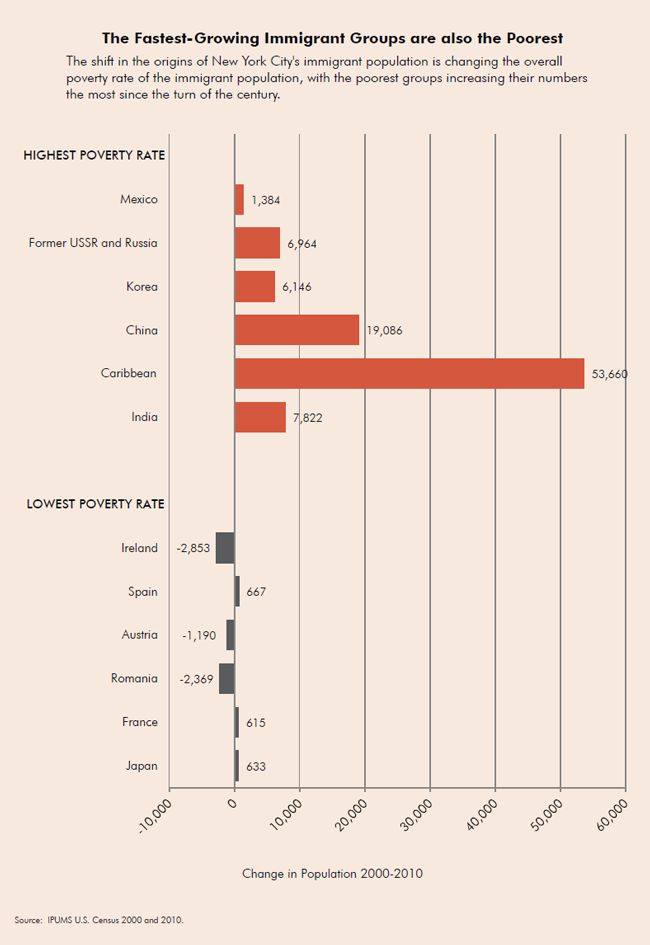

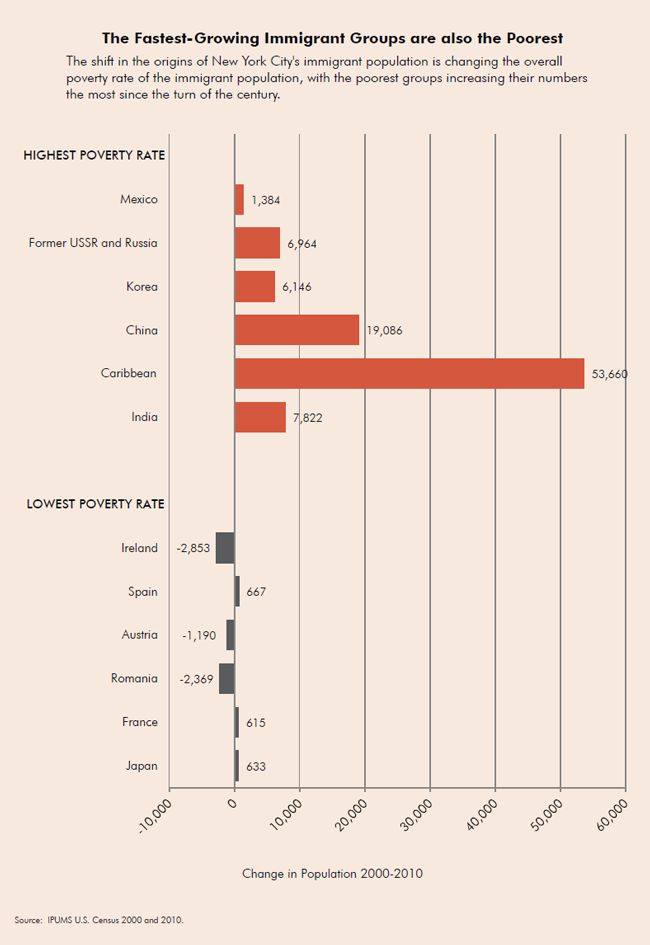

Alarmingly, this discrepancy is likely to grow in the years ahead, as the immigrant groups with the fastest growing populations of seniors are also among the poorest. The number of seniors from European countries with lower levels of poverty has actually fallen 10 percent since the beginning of the decade, while the four fastest growing groups—Chinese, Indian, Caribbean and Korean immigrants—all have poverty rates of at least 25 percent. Among Mexican immigrants, another fast-growing group, an astounding 50 percent are below the federal poverty line.

Dense pockets of poor seniors are sprouting up in neighborhoods throughout the city, including Flushing, where 52 percent of all poor Korean seniors are located, and the North Shore of Staten Island, where 36 percent of all poor African seniors live. In Sunset Park, which has experienced an enormous spike in immigrants from China, Mexico and Latin America over the last decade, nearly half of all foreign-born seniors are living in poverty.

Compounding these financial challenges, foreign-born seniors also receive much less in benefits from Social Security, since they tend to earn significantly less over the course of their working lives and thereby pay less into the system. Moreover, a much higher percentage of immigrants either don’t qualify at all for the program or haven’t enrolled. Either way, 31 percent of immigrant seniors in New York are not receiving Social Security benefits, compared to only 18 percent of the native-born seniors.