After more than a decade of skyrocketing attendance, many of New York City’s branch libraries, museums, and performing arts institutions are bursting at the seams. The average library is over 60 years old, and many are either too small to adequately serve the rising number of patrons, poorly designed for the way people are using libraries today, or in need of basic repairs just to keep their doors open. Meanwhile, dozens of the city’s cultural institutions—many of which were built more than 50 years ago—could also benefit from a makeover or an expansion to accommodate the hordes of new visitors driven by record population growth and an unprecedented boom in tourism.

But while tackling the infrastructure needs of New York’s museums, performance spaces, and libraries necessitates a new level of financial support from city government in the years ahead, it will also require fundamental changes to the city’s maddeningly time-consuming and unnecessarily expensive capital construction process for nonprofit institutions.

As this report details, infrastructure projects for libraries and cultural institutions managed by the Department of Design and Construction (DDC), the city’s chief capital construction agency, take much longer to complete and cost significantly more than similar capital projects that are managed by the institutions themselves or overseen by other governmental agencies.

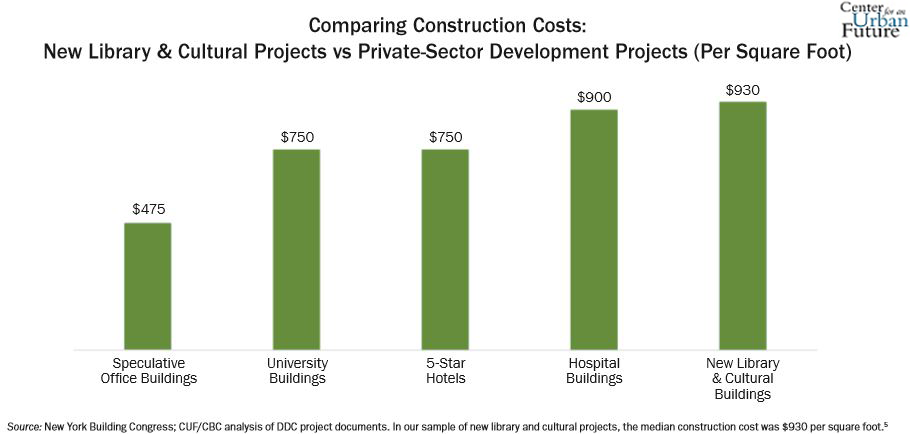

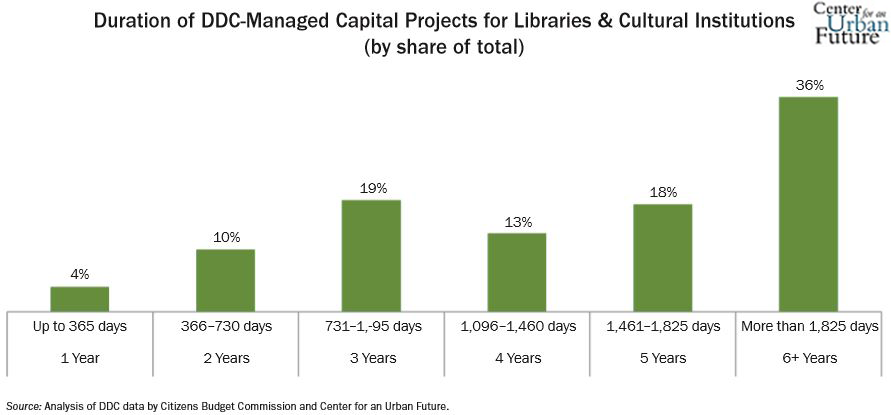

Our report features an analysis conducted by the Citizens Budget Commission (CBC) of 144 DDC-managed capital projects at cultural institutions and libraries from fiscal years 2010 to 2014. The findings are troubling. The median capital project in our analysis took more than four years to complete, and 17 lasted for more than seven years. Meanwhile, the median cost for new buildings in our sample was a staggering $930 per square foot—roughly double the cost of new office space in the city.

Beyond the data, we conducted dozens of interviews with top officials at cultural institutions and libraries, as well as architects, private construction managers, engineers, and even officials at DDC. These conversations depict a city nonprofit capital design and construction process that is badly in need of reform.

One result of this broken system is a squandering of the extremely limited capital dollars that go to library and cultural projects. Other consequences take a more personal toll on libraries and cultural organizations, and the communities that depend on them. Museums are forced to postpone the opening of long-planned exhibitions, libraries remain closed for years longer than expected, performance halls lose revenue for every day they can’t put on a show, and organizational budgets end up in the red due to higher-than-expected capital costs.

In recent years, the Center for an Urban Future (CUF) has published several studies documenting the growing importance of the city’s libraries and cultural organizations. Our Branches of Opportunity report showed that patronage at the city’s branch libraries skyrocketed over the past decade, in large part because libraries have become the go-to places to learn the essential literacy, language, and technology skills needed to get ahead today. Our Creative New York study found that the nonprofit arts and for-profit creative industries were among the fastest growing segments of the city’s economy over the past decade.

In this new report, we set out to examine a key challenge facing both libraries and the nonprofit arts sector: the capital construction process for nonprofit organizations. The report, which was made possible thanks to generous support from the Charles H. Revson Foundation, provides the most complete picture to date of city-managed capital construction projects for libraries and cultural organizations.

CUF teamed up with the Citizens Budget Commission to analyze timelines and cost breakdowns for 144 library and cultural capital projects completed between fiscal years 2010 and 2014. These projects constitute approximately one-quarter of all library and cultural projects completed during the Bloomberg administration, and all of the DDC-managed library and cultural projects completed during these five years.1 In addition to the data analysis, we conducted dozens of interviews with leaders at cultural institutions and libraries, architects, contractors, employees at city agencies, and budget experts. These conversations helped us identify the main challenges and chokepoints that plague capital projects at libraries and cultural institutions alike.

Both the interviews and financial analysis brought us to the same conclusion: city-managed capital projects for nonprofit organizations take way too long and cost significantly more than they should.

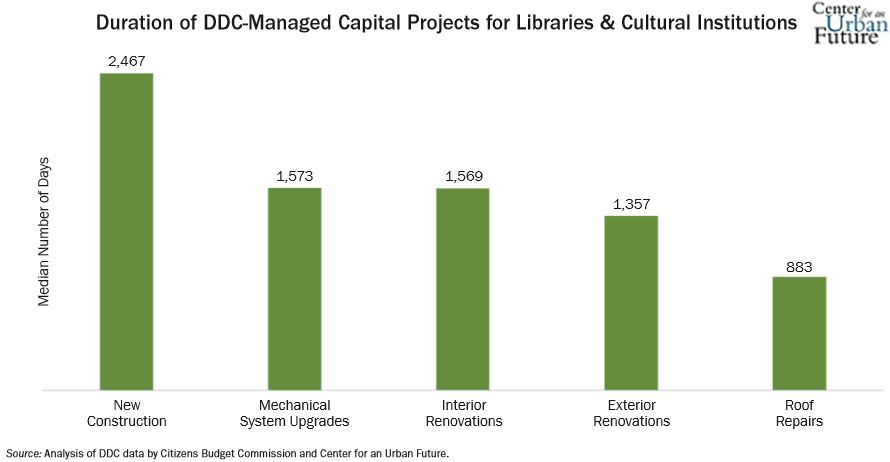

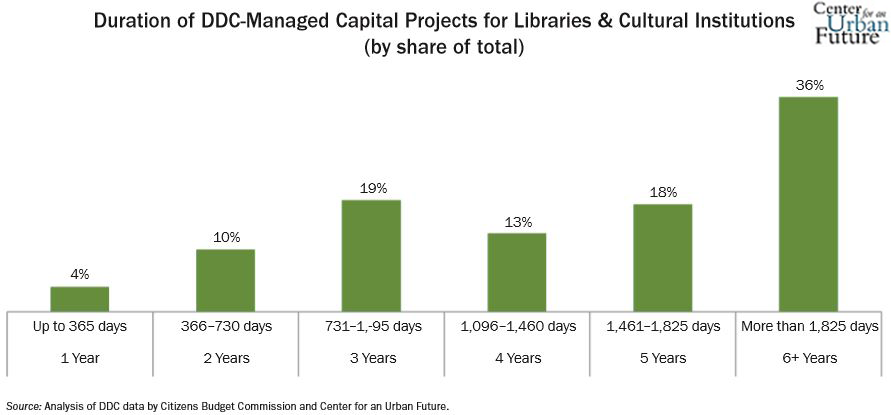

To begin with, the projects we analyzed took staggeringly long to finish. The median project took 1,550 days—more than four years—to complete. However, 36 percent of the projects took more than five years, and several lasted more than a decade. The durations are especially shocking given that most projects were relatively small and involved the replacement or renovation of isolated building components such as mechanical equipment, facades, and roofs.

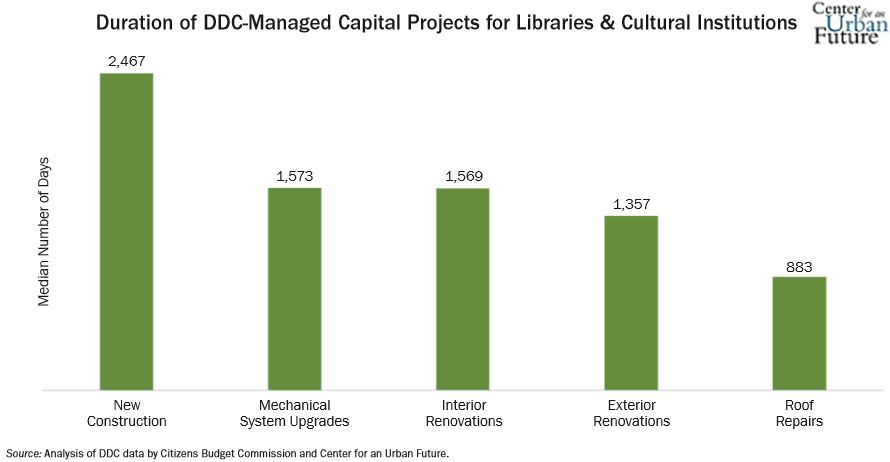

Of all the library and cultural capital projects we analyzed, the ones that involved new construction took the longest to complete—nearly seven years, or 2,467 days. But fairly routine maintenance projects also take years to finish. When broken down by project type, the median mechanical system upgrade—a category that includes the replacement and installation of fire alarms, boilers, and heating/cooling systems— took 1,573 days (4.3 years) until completion.

As one example of how seemingly simple projects can get bogged down in different stages of the process, a group of fire-safety projects at the New York Public Library (NYPL) took only three months to build and install but spent 1,499 days in the planning and approval phases before construction could even begin. One relatively small parapet reconstruction project at the Brownsville branch of the Brooklyn Public Library (BPL) got so bogged down by the many layers of approval—not just at the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) but at the Fire Department, Department of Buildings, and the Public Design Commission—that it took 1,453 days before construction started, and spanned 2,022 days (over 5.5 years) from the time the project file was opened at DDC until it was deemed substantially complete.

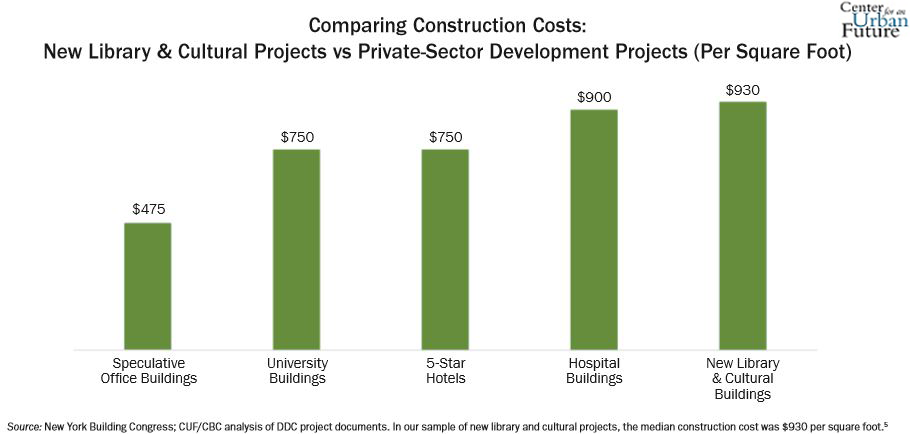

Likewise, construction costs were extremely high. Relying on DDC’s cost estimates, the median cost of construction for the new library and cultural buildings in our sample was an astronomical $930 per square foot.

This is strikingly high, even in a city with the highest construction costs in the nation. Indeed, construction costs for speculative office buildings in New York City range from $425 to $500 per square foot, according to a March 2016 analysis by the New York Building Congress. Even the most expensive private sector projects generally cost significantly less than DDC-managed library and cultural projects. For example, the cost of hospital construction—the most expensive category surveyed—averaged $800 to $1,000 per square foot. University buildings came in at $600 to $900 per square foot, and five-star hotels at $700 to $800 per square foot.

Many library and cultural construction projects in the city far exceed the $930 per square foot median cost of construction. Indeed, after filtering out the minor or highly specific capital projects included in our new construction and renovation categories, we found 12 major projects—out of 28 total—that cost more than $1,000 per square foot. That includes the Kingsbridge Library, completed in 2011, which cost $1,117 per square foot, and the Weeksville Heritage Center, completed in 2013, which cost $1,398 per square foot.

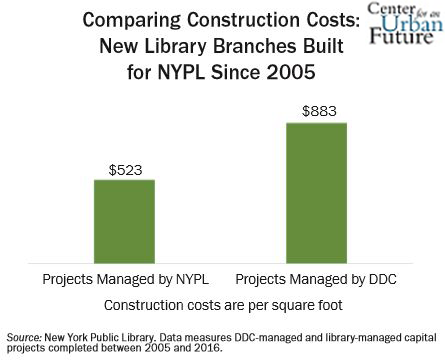

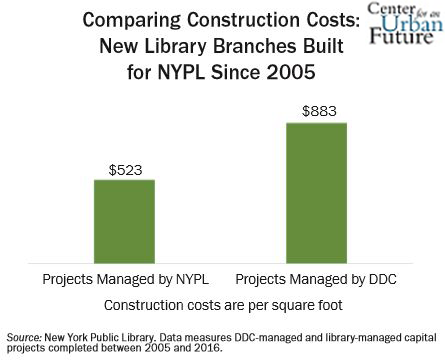

These costs also vastly exceed the prices per square foot that libraries and cultural institutions report paying for projects that they manage themselves. For example, of the six new NYPL branches completed since 2005, the average cost of construction for selfmanaged projects was approximately $523 per square foot, versus $883 per square foot for the DDC-managed projects—a 69 percent premium. When design costs are factored in, the cost difference balloons to 88 percent.6 (In a handful of instances, known as “pass throughs,” libraries and other large nonprofits receive permission from the city to manage projects themselves.)

The frequent delays and cost overruns are painful for the client institutions and the communities they serve. For example, a roof repair and Americans with Disabilities Act compliance project at the Park Slope library kept the branch closed for more than three years. As the initial project dragged on, library officials attempted to take advantage of the prolonged closure to revamp and refresh the building’s interior. However, the proposed changes triggered a cascade of new approvals, rejections, and alterations from DDC and OMB, further elongating the timeline. During the years that the 12,500-square-foot library was closed for repairs, the entire 675,000-square-foot Barclays Center was built.

“At the end of the day, our patrons suffer,” says one public library official. “When a branch does have to close for construction, the duration is longer than it should be. We have rooms offline, we have systems that don’t work. If our librarians are worried about the boiler or the HVAC, it all impacts how we run our business.”

The delays and high costs stem in large part from inefficient systems and processes at DDC and OMB, the agencies that are most involved in overseeing capital projects for libraries and cultural organizations. However, another major factor is the piecemeal way that many capital projects for libraries and cultural groups are funded—a process in which scope changes are common. In addition, there are several system-wide issues that contribute to major inefficiencies, including laws that both mandate a low-bid procurement system and prevent city projects from adopting a design-build process.

Overall, we were able to identify seven major drivers of delays and costs in city-managed capital projects for nonprofits:

The complex and time-consuming approvals process can take years before construction even begins. The three stages of the capital process that precede construction—pre-design, design, and post-design—involve an arduous multiagency review process and many stages of project scoping and cost estimating. Projects can spend months in limbo while DDC, OMB, and other agencies make determinations on scope changes, design elements, and capital eligibility, such as whether a light switch is eligible for capital funds in an electrical system upgrade.

The average project spends nearly a year waiting for approval of Certificates to Proceed. Although DDC manages the capital process for nonprofits, OMB reviews every amendment to the project. Among the projects we analyzed, it took 62 days on average for OMB to approve each amendment. For the average project, these approvals added up to 328 days.

Little accountability for the efficient and cost-effective delivery of capital projects. DDC and OMB do not track timelines and costs in a systematic way and do not keep project managers accountable to pre-established targets. Layers of review designed to protect public dollars can have the unintended consequence of contributing to delays and driving up costs.

Lack of coordination among oversight agencies. DDC, OMB, and other agencies such as the Department of Buildings, the Fire Department, and Public Design Commission too often work at cross purposes, stymieing effective project management at all phases of design and construction. Insufficient management experience at nonprofit client organizations. Many small cultural nonprofits lack experience working with city capital dollars and struggle to meet the extensive legal requirements that come attached.

Ineffective budgeting and capital planning processes and major changes in scope. The city’s discretionary funding process, which allows individual elected officials to fund projects in their districts independently, makes it difficult for OMB and DDC to create a predictable pipeline of capital-eligible projects. Scope changes are fairly common, with many libraries and cultural organizations raising additional funds for dramatically expanded projects after the design phase has begun. Each new financial infusion and scope change leads to new rounds of agency review.

Insufficient management experience at nonprofit client organizations. Many small cultural nonprofits lack experience working with city capital dollars and struggle to meet the extensive legal requirements that come attached.

Outdated and costly procurement processes. State procurement law, which generally requires DDC to hire the lowest bidder without room to compare the quality of contractors or the overall value of bids, introduces inefficiencies and misaligned incentives into the contracting process and leads to project management conflicts.

To be sure, across the spectrum of public projects funded and managed by city agencies, library and cultural projects are among the most complex. Major underlying factors that affect cost and complexity include a mix of public and private funding sources and ownership structures, some of which trigger additional state and federal capital finance rules, as well as needs that do not allow for a cookie-cutter approach to design and construction. The result is that libraries and cultural institutions are hit particularly hard by the burdens that accompany city-funded capital projects.

It’s worth noting that DDC has made a lot of progress over the past decade in the design and overall quality of the construction projects it manages. Dozens of buildings, from firehouses and libraries to theaters and museums, have won recognition from prominent critics and organizations; the Design and Construction Excellence program has even streamlined rules to make it easier for talented architects to contribute to public buildings. Moreover, this study found no evidence that these investments in quality design have contributed to long delays and cost overruns.

This report solely analyzed data from DDC-managed capital projects that were substantially completed prior to the administration of Mayor Bill de Blasio, and there are signs that the current administration is making progress. Under the leadership of Commissioner Feniosky Peña-Mora, DDC has focused more attention on improving project delivery. DDC’s 2017 State of the Agency report cites a number of achievements, including a 22 percent reduction in project approval durations from OMB and an initiative to schedule bids for release within two weeks of approval by DDC’s Law Division.

DDC’s commitment under the current administration to improving its processes is immensely encouraging, but it’s also clear that these improvements only begin to address the sources of cost escalation and delay in their oversight of capital construction projects at libraries and cultural institutions, many of which stem from citywide oversight rules—particularly those enforced by OMB—and inefficient procurement practices that are mandated by state law.

The de Blasio administration cooperated fully with us on this study, granting access to project managers and other personnel at a variety of city agencies and offices. In addition, our data analysis was reviewed by DDC officials with expertise in project management and budgeting. Although the majority of city and nonprofit employees interviewed for this report chose to speak anonymously to avoid offending other agencies and organizations, most were candid in their assessments of the city’s capital funding and management system. Together, these interviews describe a system that presents obstacles throughout the entire process, from approving the initial design brief through cutting the final check. In the words of one nonprofit executive with extensive capital construction experience, “The biggest [cost] escalator in a construction project is delay—and the city system is built to delay.”

At a time when the city appears to be heading into a period of diminishing tax revenues and reduced federal funding, it will be more important than ever for New York policymakers to ensure that the city’s capital funds are stretched as far as possible. That hasn’t been the case with respect to the city’s capital programs for libraries and cultural organizations. But the good news is that there is no shortage of promising ideas to improve this deeply flawed system.

In the final chapter of this report, we set forth 12 achievable recommendations for creating a more costefficient—and more effective—capital construction process for cultural organizations and libraries. Our recommendations include:

- Create a task force to review and reform the capital construction process.

- Start systematically tracking capital project costs and timelines.

- Streamline project approval practices and reduce redundancies between OMB and DDC.

- Simplify the design review process at DDC.

- Strengthen DDC’s data analytics team to inform smarter decision-making.

- Institute a process for nonprofits to prequalify for discretionary capital funds.

- Establish dependable funding for capital construction projects, including routine state-of-goodrepair investments

- Standardize and disseminate capital eligibility rules and requirements.

- Allow appropriate capital projects to be contracted through a design-build process.

- Expand the use of self-managed projects.

- Improve contracting by assessing value rather than defaulting to the lowest bid.

- Create a “Director of Libraries” inside City Hall.

Photo credit: Hunters Point Community Library / Steven Holl Architects