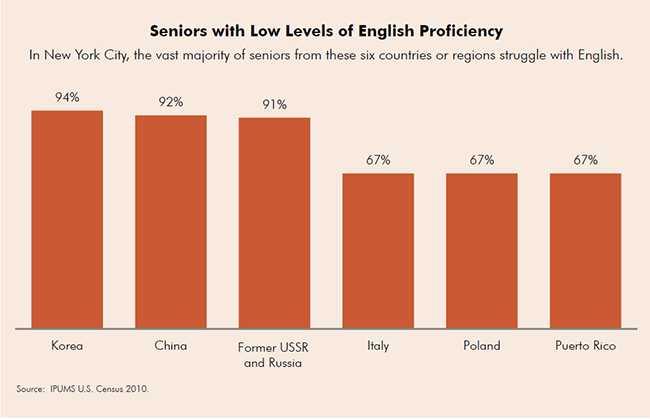

Immigrants age 65 and over also face a number of unique social challenges, and one big reason for that is unfamiliarity with the English language. Sixty percent of immigrant seniors in New York have limited English proficiency (LEP), with even larger percentages among fast-growing groups from Asia and Latin America. An astounding 94 percent of Korean seniors, 92 percent of Chinese seniors and 91 percent of Russian seniors speak English less than very well. And while seniors from Spanish-speaking countries do better by this measure, big majorities also display low-levels of English proficiency. Sixty-seven percent of Mexican seniors, 65 percent of Cuban seniors and 53 percent of Central American seniors indicate on Census surveys that they speak English poorly or not at all. Even among older Puerto Ricans, who are U.S. citizens and aren’t included as foreign-born seniors in our demographic analysis, a remarkably large share—67 percent—have low levels of English language skills.

Although English language competency is an important skill in its own right, low levels of English proficiency are also a good proxy for how well immigrants are assimilating to new norms and lifestyles and whether they are in danger of suffering from isolation and depression. According to many of the senior advocates and care providers we spoke to, depression and even suicide are surprisingly widespread among older immigrants in New York.

“Suicide is a huge problem in the Asian American community,” says Jo-Ann Yoo, managing director of community services at the Asian American Federation. “A caseworker at a Korean American senior center in Staten Island told me that senior suicide is a major community issue.They are so depressed because they come here, they don’t speak the language, they don’t know anybody, and they feel really isolated.”

“Many are isolated even within their own families,” adds Kyung Yoon, executive director of the Korean American Community Foundation (KACF). “Many immigrant seniors come [here] to take care of grandchildren,” she says, “but sometimes they find that they can’t communicate with them because they only speak English.”

To be sure, New York City offers immigrant seniors a plethora of advantages, especially when compared to other North American cities with smaller, less entrenched immigrant communities and fewer public services. Immigrant seniors here have an easier time getting around because of the city’s public transit system and have access to a whole host of amenities—from ethnic grocery stores and community-based organizations to hospitals and health care clinics. Moreover, as many community leaders readily recognized in our interviews, New York has a more robust system of senior centers and senior services than any other city in the U.S.

Nevertheless, many of these existing resources and services aren’t keeping up with the rising demand and changing geography of the city. Because of language and cultural barriers, foreign-born seniors have a harder time finding out about existing support services, including both tax and entitlement programs, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), Medicare, Medicaid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and services delivered through senior centers and other community-based organizations. In the latter case, immigrant seniors may be reluctant to participate in programs not just because they don’t know the services exist but because they aren’t linguistically accessible or culturally appropriate. A handful of providers that have been located in certain neighborhoods for years offer services that may once have been appropriate but now don’t speak to the needs of the surrounding immigrant community.

Housing is another essential resource in short supply in New York, limiting many older residents’ ability to stay with extended families and age in place. Unlike most native-born seniors, immigrant seniors tend to live in larger multigenerational households. According to the Census, 16 percent of households with a foreign-born senior consist of four or more people, compared to just 4 percent of households with a native-born senior. And, among households in which grandparents live with their grandchildren, 72 percent contain a foreign-born grandparent.

Many immigrant seniors come to this country to take care of their grandchildren, and financial strains and cultural values often make it impossible for families to choose long-term care facilities when older family members are unable to take care of themselves. The challenge is that a majority of the city’s housing stock consists of small apartments. Only 16 percent of rental units in the city have three bedrooms or more. Several community leaders in our interviews described severe strains that many families experience because of a lack of affordable housing alternatives, forcing them to opt instead for illegal conversions of apartments and basements.

“What are they doing about creating affordable senior housing?” says Maria Rivera, senior services director of the nonprofit community center BronxWorks. “Not just for middle-income baby boomers but for the seniors who are earning anywhere from $10,000 to $13,000 per year?”

Aging in place is not only important to individual seniors who would rather stay in their homes and close to their families, it also offers a much less expensive option than nursing homes. A single private room in a New York City nursing home costs an average of $396 daily or $144,540 annually. All other types of institutional long-term care facilities are also extremely expensive, significantly above the national and state averages, while the cost of home care is lower here than the national average due to lower wages paid to home care workers.

Providing support services, housing and health care to a rapidly growing senior population will of course require extensive investments and planning by a wide variety of city agencies and the nonprofit providers that depend on them. But even as this population continues to grow at an alarming pace, funding for senior housing and services has declined significantly over the years. Funding for the federal government’s primary subsidized housing program for seniors, the so-called Section 202 program, has plummeted by 42 percent nationwide since 2007.5

Meanwhile, funding for the Older Americans Act (OAA), the country’s primary source of funding for senior services, has fallen far short of demand. Between Fiscal Year 2005 and Fiscal Year 2012, New York City’s share of OAA funds declined by 16 percent.6 Local funding for senior services has dropped precipitously as well: after slight increases between 2005 and 2009, city funding for senior services dropped by 20 percent over the next five years, going from approximately $181 million in Fiscal Year 2009 to $145 million in Fiscal Year 2012.7

More than just funding, policymakers in New York will need to start planning for the aging of the city population—and the rapid growth of its older immigrant population. The graying of the city’s immigrants creates both challenges and opportunities in areas from workforce development and housing to transportation and health care delivery. Government officials would be wise to develop strategies for increasing access to government benefits, expanding the supply of larger apartments for extended families, tapping the expertise of older immigrants, ensuring that more of the centers that offer meals for older adults provide ethnic food options (not just franks and beans, as one immigrant advocate told us), improving access to translators and taking advantage of technology to help older adults access services. They should also develop stronger relationships with the community-based organizations that have the trust of immigrants in neighborhoods across the city—and which are well-positioned to help ensure that more government services reach older immigrants.

The Bloomberg administration has taken some important steps, like the creation of Age Friendly New York City. Still, much more needs to be done to make New York not only a great place for immigrants but a great place for immigrants to grow old.