Click here to download this policy brief as a PDF.

New York’s community colleges have a key role to play in elevating poor and working poor New Yorkers into the ranks of the middle class. The economy is producing few decent-paying jobs for people with only a high school diploma, and community colleges offer the most accessible path for people to obtain a post-secondary credential. However, tens of thousands of New Yorkers who can only afford to enroll in these institutions on a part-time basis are struggling to remain in school long enough to earn a credential—and one of the biggest reasons is the state’s outdated financial aid system, which effectively bars part-timers from benefiting from the Tuition Assistance Program (TAP).

Part-time students now account for 42 percent of those enrolled at SUNY and CUNY community colleges, up from 32 percent in 1980. Yet, in 2013, less than 1 percent of the nearly 150,000 part-time students enrolled at the state’s 36 community colleges received financial aid through the state’s TAP program. At CUNY community colleges, just 91 out of nearly 40,000 part-time students received TAP funds to help pay for school that year.

The TAP program is comparatively generous in other ways, but New York is one of only 14 states to sharply limit access to part-time students. The state’s eligibility rules require that students be enrolled full-time for two consecutive semesters before they can enroll part-time and still qualify for TAP.1 And once they meet these requirements, students are only eligible for a total of six semesters of schooling.

These restrictions are a big reason why so few part-time students who enroll in community colleges actually earn a degree or professional certification. The 6-year graduation rate at the state’s 36 public community colleges is 35 percent (29 percent at CUNY community colleges), but the rates for part-timers are even lower. Nationally, research has found that student debt and lack of access to financial aid are the key problems associated with low completion rates.

Some educators have argued that policymakers should not be encouraging students to enroll part-time, since data suggests that full-time students have a higher likelihood of graduating. But scores of poor and working poor New Yorkers with family obligations or paltry savings simply can’t afford to quit their jobs and enroll in classes full-time. Instead of excluding thousands of low-income students from financial aid opportunities because they can’t afford to attend school full time, state officials should give these residents the tools to succeed in college. Easing TAP’s eligibility restrictions for part-timers is a good place to start.

Expanding Access to Post-Secondary Credentials

With hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers either unemployed or stuck in low-wage jobs, there is a clear need to increase the number of New Yorkers with a post-secondary credential.

At the end of 2013, New York State was home to 674,543 people between 18 and 64 who did not have a job but were actively seeking one, according to an analysis of Census data by the Population Reference Bureau on behalf of the Working Poor Families Project.2 Meanwhile, nearly 2.7 million adults in the state are employed work in low-wage jobs—33.7 percent of all New Yorkers over the age 18, compared to a national average of 28.2 percent.3

There is an undeniable connection between educational attainment levels and those who are poor or working poor. For instance, more than 60 percent (61.4 percent) of the state’s working poor families feature at least one parent who does not have any postsecondary education.4

Despite all this, only 5.4 percent of adults in New York are enrolled in post-secondary institutions at least part time, well below the national average of 7.0 percent.5

Community colleges offer the primary route out of poverty for disadvantaged New Yorkers. For the 2012-13 academic year, in-state tuition and fees for SUNY community colleges averaged $4,367, compared with $7,099 at SUNY four-year colleges and universities, $19,142 at proprietary colleges, and $34,536 at New York’s private four-year institutions of higher learning.6 The relatively low tuition and open access model central to community colleges removes many of the usual barriers that nontraditional learners face.

Part-Time Students on the Rise

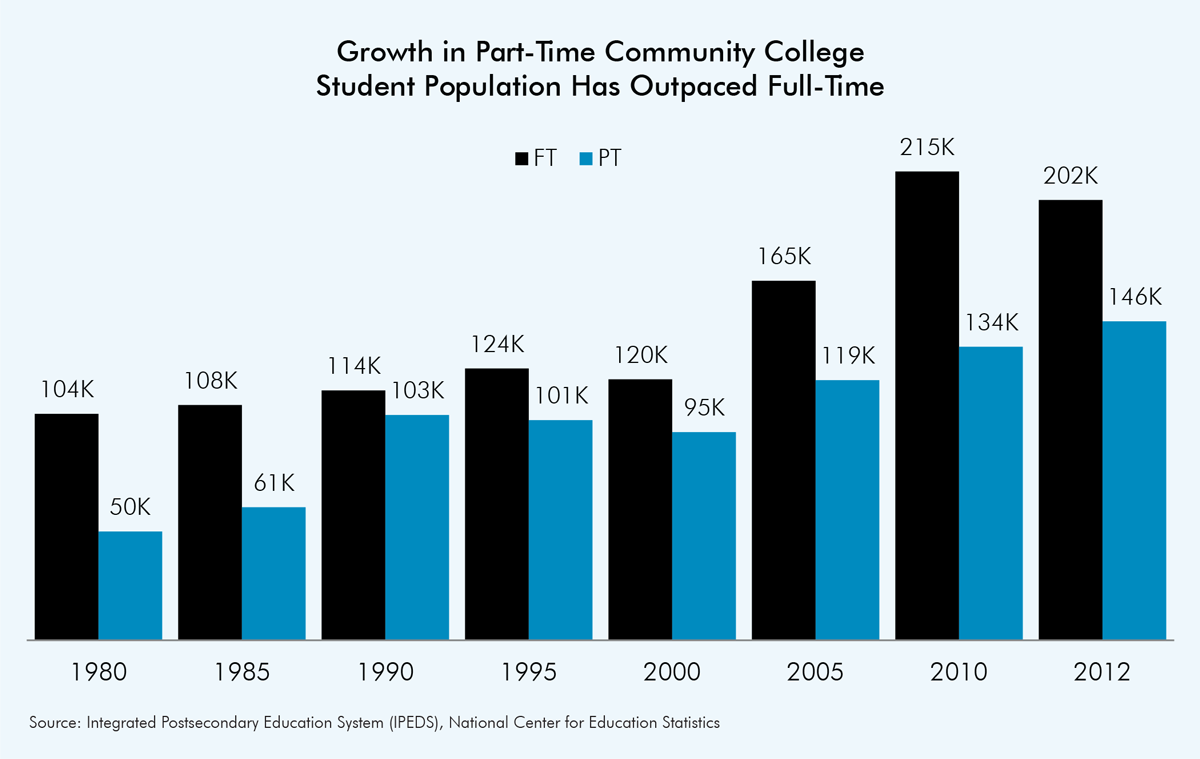

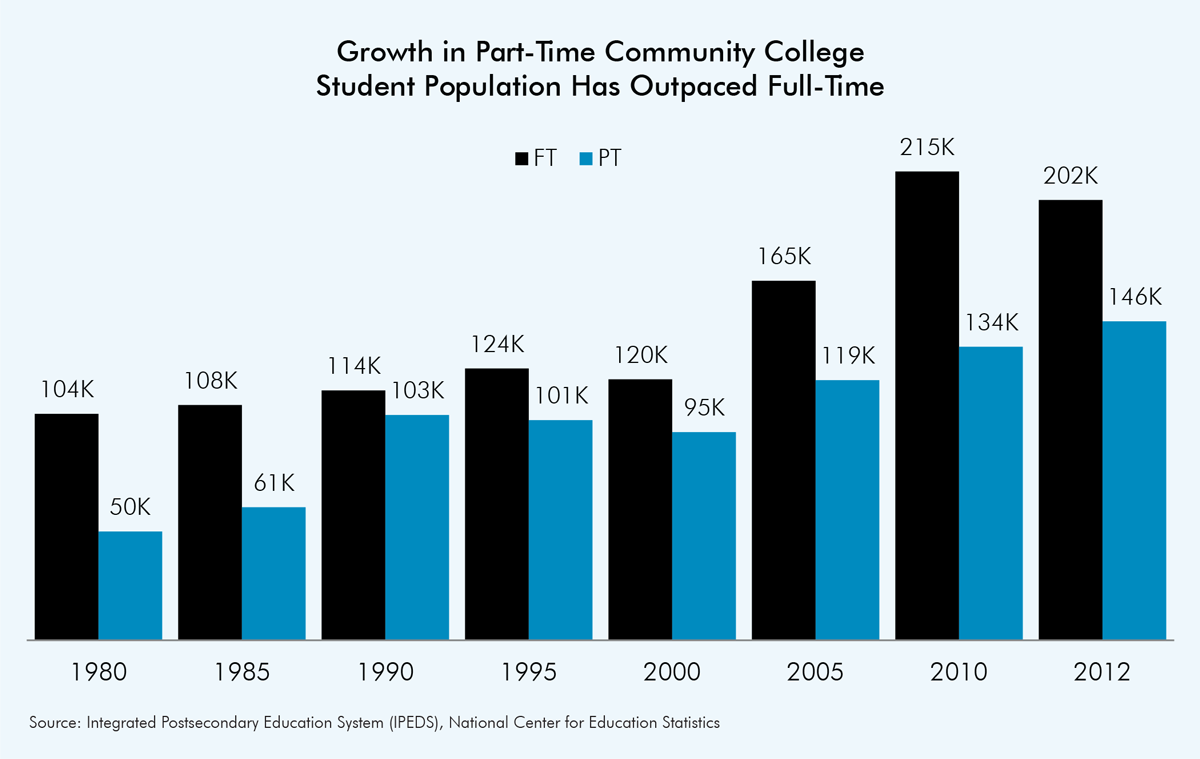

But for many, enrolling part-time is the only viable option. In recent years, more and more New Yorkers have taken this route to a post-secondary credential. Between 1980 and 2012, the number of part-time community college students in New York State has increased by 193 percent (from 49,821 to 146,041), while the number of full-time students has increased by 94 percent (from 103,730 to 201,667).

Although the number of part-time students at both four-year and two-year colleges has increased rapidly, the vast majority of the state’s part-time students are enrolled in community colleges. In the 2012-13 school year, there were 347,708 students attending New York State community colleges, with 146,041 of them attending part-time.

What is TAP and PTAP?

The Tuition Assistance Program (TAP) is the second-largest state financial aid grant program in the nation, and last year spent $935.6 million on awards to 372,527 students. In the 2013-2014 academic year, the maximum award was $5,000 and the average student received an award of $2,511. In the same year, 2,430 part-time students across the state received awards through Part-Time TAP (PTAP), TAP’s sister program for students who attempt at least six but less than 12 credits. The average PTAP award in the 2013-2014 school year was $831. Earlier this year, the state legislature voted to increase the maximum award for full-time students to $5,165 from $5,000.

In order to be eligible for TAP students must be U.S. citizens, residents of New York State and must have either graduated from a U.S. high school, obtained a high school equivalency diploma, or passed an Ability to Benefit test administered by the New York State Education Department. TAP is only available for undergraduate students who matriculate on a full-time basis in the spring or fall semesters and maintain at least a C average. Students pursuing two-year associate’s degree programs can get TAP for a maximum of six semesters (three years), while Bachelor’s degree candidates can draw down TAP for eight semesters (four years), unless they are pursuing an accredited five-year Bachelor’s degree.

Awards are subject to income limits, and are calculated based on seven schedules that vary by household income, dependent or independent status and the first year that the student drew down TAP aid. Undergraduate students who depend on their parents or independent students who have dependents must earn $80,000 or less annually in net taxable income, married independent students without dependents must earn $40,000 or less, and single independent students with no children must earn $10,000 or less. Awards are based on the maximum TAP award available in the semester when the student received TAP for the first time, which for students returning to school after many years can be considerably different from the current award schedules.

In order for part-time students to be eligible for Part-Time TAP (PTAP) they must meet the above requirements, but must have also first completed two consecutive semesters of full-time study (at least 12 credits per semester).

Excluding Part-Timers from TAP

But because of stringent eligibility requirements, only a tiny fraction of students enrolled part-time receive any financial aid from the state. In the 2013 fall semester, just 91 out of 39,814 part-time CUNY community college students received Part-Time TAP (PTAP). At SUNY community colleges, only 1,244 out of 101,858 part-time students (1.2 percent) received PTAP that semester.7

Part-time students have limited options when it comes to financial aid, and are often forced to either pay out of pocket or take out loans in order to pay for their education. In addition, because part-time students are also likely to require more time to complete their degrees than students who are attending college full-time, they are likely to run out of TAP eligibility before they get a chance to complete their degrees.

“Working adults are returning to school in droves,” says Kevin Stump, who previously led the Coalition to Reform the New York Tuition Assistance Program and is now the director of the Roosevelt Institute Campus Network, a campus-based leadership development organization. “In order to meet that demand we need to incentivize them to go to school without getting themselves in debt or stopping out.”

Yet completion rates are distressingly low. Just 35 percent of community college students graduate within six years of matriculating.8 And many of these students drop out as the costs of continuing with their education become untenable.

Aggregate numbers show that TAP is among the most generous state grant-based higher education financial aid programs in the nation. In the 2012-13 school year the state spent $931.1 million on TAP, a 19 percent increase over 1999-2000 after inflation, while the average U.S. state spent $177.3 million.9 The average student received an award of $3,049 in that school year, and the maximum TAP award was increased just this year to $5,165 from $5,000. Despite this, part-time students in New York State are faced with the double whammy of being mostly ineligible for state grant aid, and facing some of the highest community college costs in the nation. Tuition and fees at New York State’s community colleges are more than 50 percent above the national average, and four times higher than those of California, which boasts the most affordable community colleges in the nation.10

Tuition and fees comprise about a quarter to a third of the cost of attendance and that alone has increased by 58 percent at CUNY and 48 percent at SUNY since 2006-2007.11

Moreover, the vast majority of community college students—and in particular those older students who are returning to school and juggling outside work and family obligations—have fewer resources to pay for school. They qualify for fewer outside grants, including Pell, and low-cost loans, and they earn comparatively little in their current jobs. While the median family income in New York State is $69,968 per year, the median family income for those with just a high school degree is $17,765. Single parents who have a high school degree or less have a median income of just $16,505 per year.12

Though TAP is technically available to part-time students, current eligibility requirements make it all but impossible for the majority of them to qualify, much less draw down aid for the entire duration of their college career. TAP eligibility criteria are structured to cater to students who drop down to part-time after attending full-time, which gives full-time students the opportunity to lower their course load for a semester or two if outside obligations get in the way. But those students who need to start with a lower course load and increase their courses to a full-time level later on are barred from receiving any financial aid. This disqualifies tens of thousands of nontraditional students every year, and requires many others to take on a bigger course load than they’re ready for.

Many students who take on more than they can handle end up performing poorly in some of their classes and losing TAP eligibility because of poor academic performance. Financial aid counselors and college administrators point out that if barriers to accessing PTAP were lower, it would allow students to take only the courses they need and not pad their schedule with courses they don’t. “The lack of a good part-time component hurts these students,” says George Chin, who was CUNY’s director of financial aid for 26 years and is now a senior federal policy consultant for the American Association of State Colleges and Universities (AASCU). “There are some students who will force their schedules to be full-time in order to get TAP, but they may not do as well because they overload themselves. They either have to drop a course at some point, or their grades may not turn out as good as they could have been.”

Due to the full-time requirements for TAP, many other potential students never even enroll.

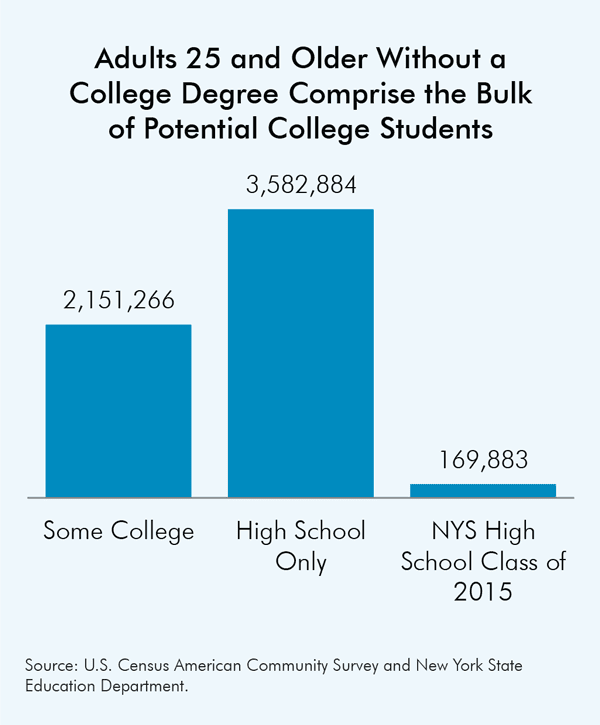

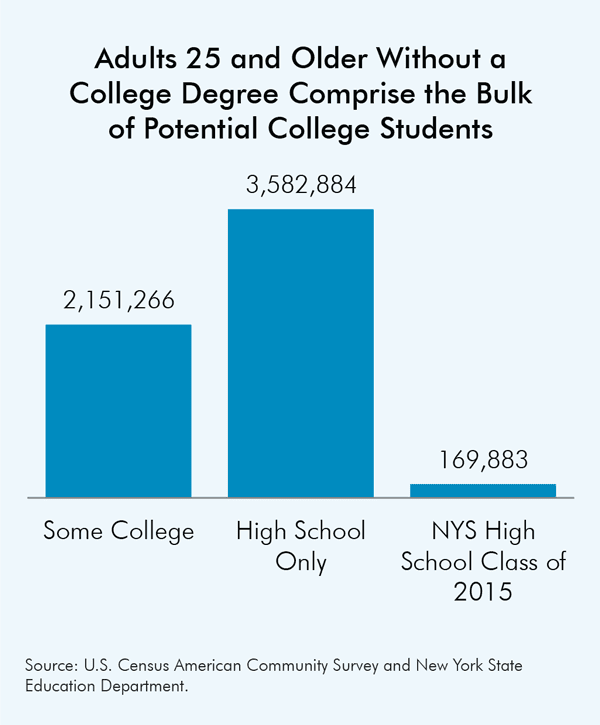

Sixteen percent of New Yorkers ages 25 and older (about 2.2 million people) are counted by the Census as having “some college;” and of those, 72 percent have one or more years of postsecondary education under their belts but have not earned a degree. An additional 3.6 million New Yorkers over 25 have only a high school degree.13 In contrast, the entire state of New York is estimated to produce only 169,883 high school graduates in the class of 2015.14

In other words, despite the much larger pool of potential students who are older, already working and in need of additional training and education, TAP is structured to serve the traditional college student who enrolls full-time right out of high school.

“If PTAP were available from the beginning, people would be less afraid to pursue an education,” says Sandy Jimenez, a college counselor at the Goddard Riverside Community Center in Upper Manhattan. “A lot of times when adults are going back to school it’s because they want to get skills to get a better job and move up in society, but they are discouraged if they have to borrow.”

According to one education official in Illinois, a state that has offered state grant aid to part-time students since 1974, the logic of offering part-time aid exclusively for students who were already studying full-time is counterproductive. “You have it backwards [in New York],” says Susan Kleeman, the managing director for research and policy at the Illinois Student Assistance Commission (ISAC), the entity that administers state financial aid in Illinois. “It’s not the full-time person who goes down to part-time that graduates,” she says, “it’s the part-time person who gets close to graduating and goes up to full-time that graduates. You are actually picking the group that is less likely to succeed, the group that went in for a year, didn’t do so well, and is now part-time.”

Another TAP restriction that places an undue burden on many part-time and nontraditional students is the six semester (or three year) eligibility window. Students who have to study for extended periods on a part-time basis have an extremely hard time finishing their studies in just three years. Making matters worse, many community college students—both nontraditional students and traditional ones—require extensive remedial coursework and will not begin to finish courses that count toward their degree until their second or even their third semester. In 2011, 75 percent of first-year students at CUNY community colleges required remediation in either reading, writing or math, and 25 percent of students required remediation in all three subjects.15

“As soon as they start taking remedial courses the clock starts ticking on TAP,” says Kate Pfordresher, the research and policy director at CUNY’s Professional Staff Congress, a faculty union. “The vast majority cannot complete their coursework before TAP runs out.”

Together, the three-year eligibility window and the requirement that students enroll full-time before they can qualify for PTAP make it extremely difficult for nontraditional students to plan their course load and path toward graduation.

Moreover, part-time students would benefit from the option of taking summer courses in order to make faster progress towards degree completion, but TAP is not available during the summer. Because part-time students must schedule their classes around outside obligations, not having TAP available during the summer needlessly reduces students’ flexibility about when they can take courses. The annual hiatus can also erode the momentum students may need to stay on track towards degree completion.

“Students who want to accelerate in summer have few options for funding their education,” says LaSonya Griggs, the director of financial aid at Tompkins Cortland Community College. “Even if a student wants to and have the ability to do so, they can’t afford to.”

Students rarely attend part-time for their entire college careers. They often switch between full-time and part-time enrollment depending on work or personal schedules and availability of classes. For instance, a working adult may not be able to take his or her required courses in a given semester because the times at which the classes are offered conflict with other obligations. If a student can’t maintain full-time status by filling their schedule with another required class, he or she is left with two bad choices: take an unnecessary class to maintain full-time TAP eligibility or drop to part-time and receive less aid or no aid at all.

“If a student wants to take one course and winds up taking two to get aid they’re wasting money,” says Kleeman of ISAC.