In a space-starved city built from stone, brick, and steel, parks function as essential public infrastructure. These vital green spaces provide cost-free leisure and recreation in every corner of New York City, strengthening the economic and physical health of communities and providing a backyard for millions of residents. With the city’s population at an all-time high and record numbers of tourists, New York’s parks and playgrounds are busier—and more crucial—than ever before.

But a significant share of the city’s public parks are several decades old, years behind on basic maintenance, and increasingly at risk of infrastructure failures. The average city park is 73 years old. Roughly 40 percent of the city’s pools were built before 1950, as were nearly half of the 53 recreation centers in parks citywide. Waterfront facilities in parks—piers, bulkheads, marinas, and docks—are, on average, 76 years old.

Despite all this, the average city park last saw a major renovation in 1997. According to the best available data, 20 percent of parks citywide have not undergone a major infrastructure upgrade in 25 years.1 Meanwhile, for decades New York City has provided too little money for basic maintenance and too few staff—including plumbers, masons, and gardeners—to keep critical parks assets from deteriorating and mitigate problems before they grow.

Although the city’s parks are not yet experiencing a full-blown maintenance crisis, serious cracks are showing. Many parks with old drainage systems experience flooding for days following a rain shower. Too many retaining walls in parks are near the end of their useful lifespan. More than 20 percent of inspected park bridges are seriously deteriorated. Just as years of underinvestment in New York’s century-old subway system led to a transit crisis, the maintenance challenges at city parks could quickly get a lot worse if more isn’t done to upgrade and maintain these aging assets.

To his credit, Mayor Bill de Blasio has taken some important steps to address these problems. Since 2014, the city has launched the Community Parks Initiative and Anchor Parks Initiative, directing hundreds of millions of dollars to improve chronically underfunded parks. The Parks Department is also overseeing the system’s first-ever needs assessment, which will begin to document the specific capital needs of the city’s more than 1,700 parks.

However, much more will need to be done to shore up the city’s aging parks system. We estimate that the city will have to invest at least $5.8 billion over the coming decade to address the system’s infrastructure problems. This total only includes the known repair or replacement costs of existing infrastructure, not new structures or additions to parks. This report identifies key elements of parks infrastructure most in need of revitalization, and provides a blueprint for bringing New York’s parks system into the 21st century.

This report, funded by the Stavros Niarchos Foundation, offers a new level of detail about the infrastructure needs of New York City’s parks—including invisible infrastructure, pathways, built facilities, and landscape—and encompasses both well-known facilities like playgrounds and bathrooms, and lesser-recognized yet integral components, such as drainage systems and retaining walls. The report also advances more than a dozen practical recommendations for city officials, designed to address the infrastructure challenges facing the city’s parks.

Researched and written by the Center for an Urban Future, A New Leaf is the culmination of a year of reporting and analysis on the current state of the city’s parks system. It is informed by an extensive analysis of data from the Department of Parks and Recreation (DPR), and interviews with over 90 park officials, park volunteers, open space advocates, elected officials, community board members, landscape architects, and horticulture experts in New York and nationwide. Our research also greatly benefited from consultation with New Yorkers for Parks, a citywide research and advocacy organization championing quality open space.

To supplement our research, we also visited 65 parks citywide—from southeastern Queens to the northern reaches of the Bronx; in high-, middle-, and low-income communities; and of all sizes—to document the most persistent problems. In one day alone, six researchers captured conditions at 30 parks across all five boroughs: a systemwide snapshot of the needs of New York City’s parks system on any given day.

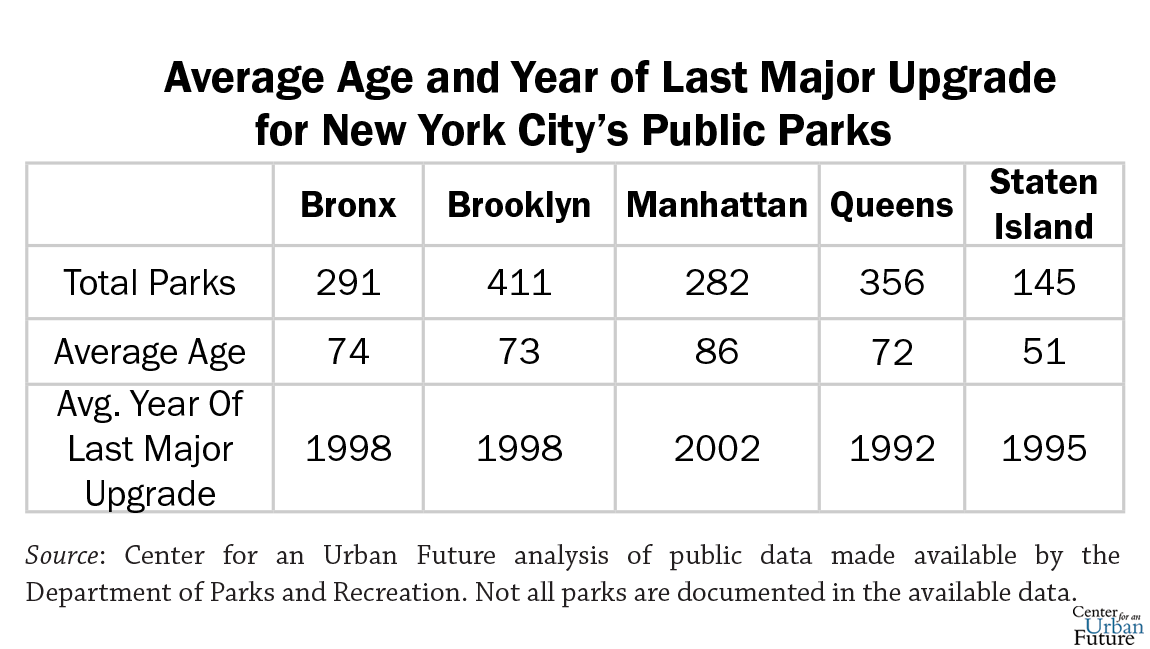

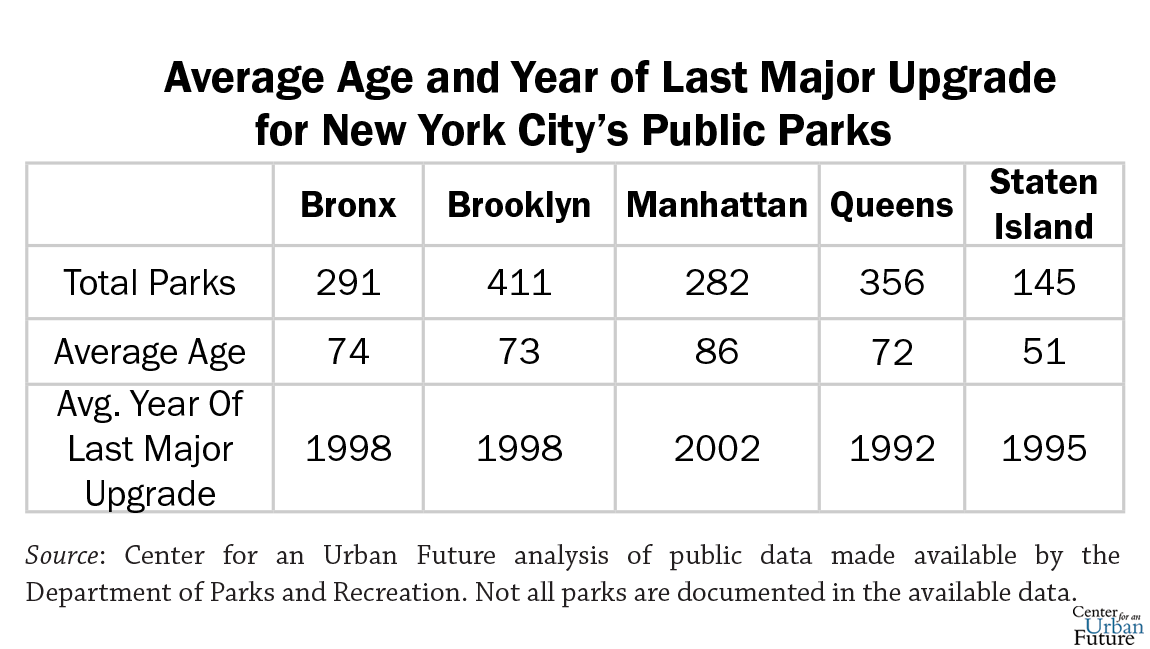

New York’s parks are now some of the most frequented in the world, with over 100 million visits annually. While reflective of New York’s growing prosperity, this historically high usage places an unprecedented burden on the city’s parks infrastructure, which shortens the natural lifespans of amenities and increases the demand for regular maintenance. This rising need takes a toll on a system in which the average park was built before World War II. Across all five boroughs, most parks are at least half a century old: the average Brooklyn park is 73 years old; the Bronx, 74; Manhattan, 86; Queens, 72; and Staten Island, 51. A quarter of New York’s parks are at least 84 years old, and one park in 10 was built before 1898.

Problems exacerbated by the age of the parks system are compounded by deferred maintenance and a lack of infrastructure upgrades, which means that aging parks often go decades without significant investment in both aboveground and below-grade infrastructure. Based on this report’s analysis of historical records and capital projects data from the Parks Department, a city park saw its last major renovation, on average, in 1997. Citywide, 20 percent of parks have not undergone a major infrastructure upgrade in 25 years. That share is even higher for smaller parks: 34 percent of parks under one acre have gone at least two decades without significant capital work. Overall, at least 46 parks, triangles, and plazas in New York have not received significant capital investment in nearly a century. At least 5 of Brooklyn’s 411 parks saw their last major renovation in the 1980s. Nearly 70 percent of the parks in that borough were last renovated before 2000, while at least 39 Brooklyn parks haven’t received major capital work since opening, according to our analysis of the only available data—in eight cases, over 100 years ago. Queens has a total of at least 37 parks that are long overdue for revitalization, including at least six that haven’t undergone a major renovation for over 100 years, and 31 for over 50 years. Manhattan has at least six parks that haven’t been upgraded significantly in more than 100 years, and at least nine for over 50 years. Staten Island has at least seven parks that haven’t received any major upgrades for over 50 years.

Problems exacerbated by the age of the parks system are compounded by deferred maintenance and a lack of infrastructure upgrades, which means that aging parks often go decades without significant investment in both aboveground and below-grade infrastructure. Based on this report’s analysis of historical records and capital projects data from the Parks Department, a city park saw its last major renovation, on average, in 1997. Citywide, 20 percent of parks have not undergone a major infrastructure upgrade in 25 years. That share is even higher for smaller parks: 34 percent of parks under one acre have gone at least two decades without significant capital work. Overall, at least 46 parks, triangles, and plazas in New York have not received significant capital investment in nearly a century. At least 5 of Brooklyn’s 411 parks saw their last major renovation in the 1980s. Nearly 70 percent of the parks in that borough were last renovated before 2000, while at least 39 Brooklyn parks haven’t received major capital work since opening, according to our analysis of the only available data—in eight cases, over 100 years ago. Queens has a total of at least 37 parks that are long overdue for revitalization, including at least six that haven’t undergone a major renovation for over 100 years, and 31 for over 50 years. Manhattan has at least six parks that haven’t been upgraded significantly in more than 100 years, and at least nine for over 50 years. Staten Island has at least seven parks that haven’t received any major upgrades for over 50 years.

Although some of these parks are likely to have received small-scale investments over the years, our research found no existing records of substantial renovations or upgrades in the Parks Department’s historical records, records of capital spending, or news reports. For example, Newtown Barge Playground in Greenpoint hasn’t received a major upgrade since 1972. Beach Channel Park, a 12-acre strip of waterfront land in the Rockaways, hasn’t been renovated since it was added to the parks system in 1930.

The numbers are particularly notable on the neighborhood level. In Woodside, 45 percent of parks haven’t received a major renovation since 1993. In Bushwick, the share is even higher, at 67 percent; in Riverdale, it’s 71 percent. The result is that hundreds of the city’s public parks are facing serious infrastructure challenges, whether from decaying drainage systems and crumbling bridges or leaking recreation centers and struggling horticulture.

Perhaps the most pressing infrastructure need is invisible: damaged or inadequate drainage systems below the ground and underwater that are hidden from view. Cracking, blocked, and insufficient drainage systems—the catch basins, sewers, and wastewater lines responsible for bringing water in and out of a park—impose one of the most challenging burdens on parks citywide. This is in part a function of age: in fact, many parks drainage systems still use clay pipes from the mid-20th century.

Today, many New York City parks can hardly handle the slightest downpour. Out of the 65 parks we surveyed, nearly half had notable drainage issues—more than two days after the last rain shower—including submerged pathways and flooded areas. At Forest Park in Queens, for example, multiple catch basins are collapsed, and several roads and paths flood every time in rains. Almost every park administrator we interviewed cited poor drainage as a major problem for the city’s parks. “We really struggle with drains,” says Susan Donoghue, administrator of Prospect Park and president of the Prospect Park Alliance. “We have incredible flooding, rivers that are forming in grassy areas, where there’s supposed to be turf. Our drains are old and broken and need to be fixed. It’s debilitating, and we can’t keep up.”

Of equal concern are the parks system’s retaining walls: the vertical structures that hold up hundreds of parks citywide, preventing landslides and forestalling erosion. Often built at the park’s inception and labor intensive to maintain, many retaining walls in parks are nearing the end of their lifespans and few had been comprehensively inspected until just the past year. For those walls that have been assessed, the price tag is high; recent reconstruction of retaining walls and seawalls at just eight parks citywide cost over $20 million. Some, like the crumbling 160-year old wall holding up Fort Greene Park, could cost far more. “Virtually every retaining wall you see has a crack in it,” says one Parks Department official, who spoke with us on the condition of anonymity. “It’s a safety issue.”

The Parks Department is also responsible for 148 miles of coastline, including beaches, marinas, and docks—properties that are extremely expensive to maintain, yet integral to the health of the city’s coastline. However, due to rising costs, growing usage, and decades’ worth of deferred maintenance, the city’s piers, bulkheads, beaches, and marinas are increasingly vulnerable, leading to several recent collapses.

The waterfront facilities maintained by the Parks Department are 76 years old, on average, which is a highly advanced age for infrastructure that takes constant abuse from water and weather. According to the city’s most recent Asset Information Management System (AIMS) report, which tracks the condition and maintenance schedules for capital assets with a replacement cost of at least $10 million, the recommended maintenance needs for the Parks Department’s waterfront facilities was just $4.3 million in FY 2016—a number that barely captures a fraction of what the coastline demands. By comparison, reconstruction of the piers at the World’s Fair Marina in Queens, which had to be shut down due to damage from Sandy and long overdue maintenance, could ultimately cost more than $36 million. Experts agree that dozens of piers, seawalls, and bulkheads are likely to be in similar condition, but have not been inspected.

Park pathways—the roads, walking trails, sidewalks, and bridges that crisscross parkland—pose similar concerns due to age and wear, especially the city’s numerous park bridges. Many date to a park’s initial opening, with one in five inspected park bridges found to be seriously deteriorated. “Bridges are a big problem,” says one Parks Department official. “Several bridges were built during the 1930s and 1960s, and weren’t inspected until recently. They went under the radar. Because they weren’t in the system, some bridges weren’t regularly inspected.” According to the 2016 annual bridge survey by the Department of Transportation (DOT), 20.8 percent of all bridges operated in conjunction with the Parks Department received a rating below 4, which denotes “serious deterioration, or not functioning as originally designed.”2 One bridge—a pedestrian bridge in Flushing Meadows Corona Park on the south side of Willow Lake—received a 1 for its condition, meaning “potentially hazardous.”

Built facilities in city parks, especially park bathrooms, also pose significant infrastructure challenges. The structures are often as old as a park, leaving them highly susceptible to gradual deterioration. In other cases, a lack of modern plumbing means that bathrooms haven’t been used in years. Our researchers observed issues at nearly half of the parks we surveyed citywide, including flooding, broken fixtures, or nonfunctional toilets. Many of the comfort stations surveyed were closed entirely.

Unlike many other components of the parks system, this report finds playgrounds to be in a much-improved state of repair. But many residents and neighborhood advocates in low- and middle-income communities say that their playgrounds too often feature broken or decaying equipment and lack the modern play surfaces and structures of better-funded parks. “Thomas Jefferson Park had one of the highest playground injury rates in the city,” says Marie Winfield, founder of Friends of Thomas Jefferson Park and a former member of Manhattan Community Board 11’s parks committee, in East Harlem. “Harlem River Park is another one. It’s just general disrepair—things that are broken with the playgrounds. For the rest of the smaller parks, it’s the same sorts of issues.” Our data analysis finds that 63 of the city’s playgrounds have not received major capital investment in over 50 years. This pattern is especially prevalent in Queens, where approximately 25 of the borough’s 66 listed playgrounds saw their last major renovation in the 1960s or earlier, according to our analysis of the only available records.

Nearly half of the city’s DPR-operated recreation centers were built prior to 1950, resulting in frequent roof leaks, broken HVAC systems, and chronic plumbing and electrical problems.3 Likewise, 40 percent of park pools were built in the 1930s, all of which—aside from McCarren Park Pool, which is still undergoing restoration work—saw their last major renovation in the 1980s.4

In addition to various built structures, the city’s diverse park landscapes—including horticulture, natural areas, and trees—face serious infrastructure challenges of their own. Our survey identified horticultural problems, such as dead plantings or rampant weeds, at over 35 percent of the 65 parks visited. The result is that many parks lack anything but the most minimal plantings—and even those are a struggle to maintain.

The challenges facing parks infrastructure did not appear overnight. Instead, they are the result of underinvestment in repair and maintenance over the course of decades and a system that makes it uniquely difficult to prioritize infrastructure when compared to other cities. Our research finds five key drivers of the parks system’s infrastructure problems, which will have to be addressed in order to make lasting progress.

Maintenance is seriously insufficient, leading to decay and collapse of parks infrastructure. For decades, New York City has underinvested in the basic upkeep and maintenance of its parks, and this maintenance neglect has contributed to larger and larger infrastructure problems. In Flushing Meadows Corona Park, for example, infrastructure built for the World’s Fair in 1964—including the Passerelle Pedestrian Bridge and the World’s Fair Marina—went decades without systematic assessment or repair, leading to the need for total reconstruction. The same is true for parks assets citywide, whether it’s a damaged drainage system that relies on clay pipes and results in extensive water damage, or a pier that collapses into the river before it can be repaired.

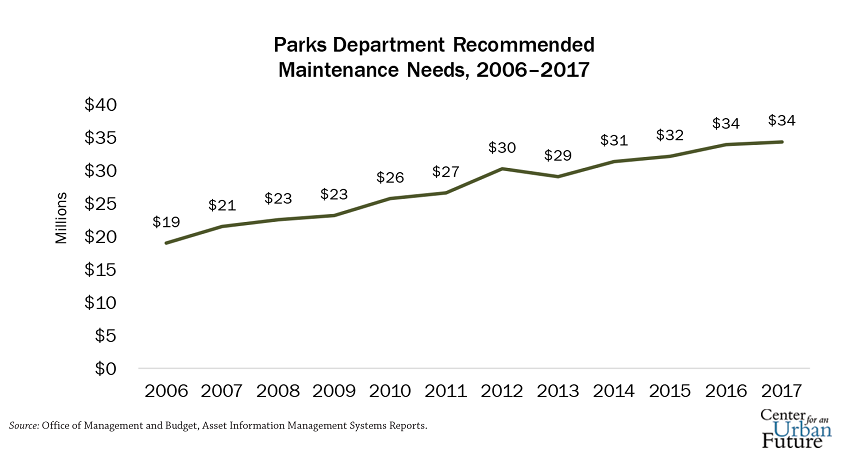

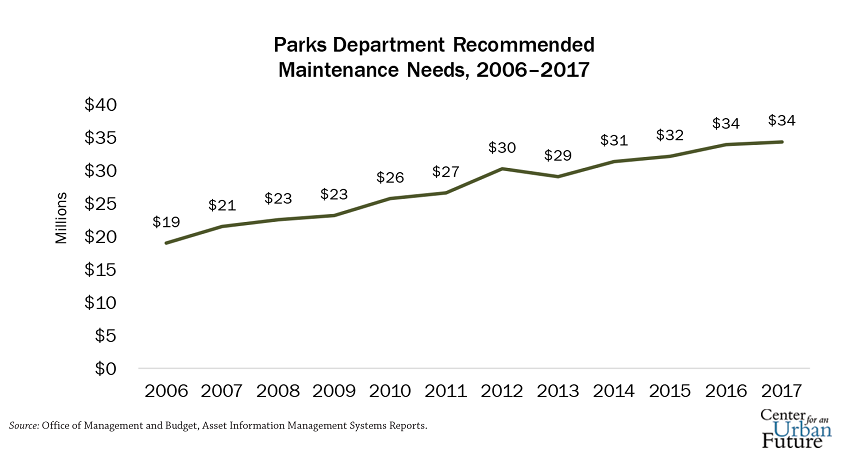

Maintenance needs have increased rapidly over the past decade, as documented by the Parks Department’s own maintenance requests. Recommended maintenance needs shot up 143 percent between FY 2006 and FY 2016, from $14 million to nearly $34 million. In FY 2016, however, just 12 percent of that request was actually funded—one of the lowest rates among city agencies.5 What’s more, those stated needs may be vastly understating the issue—in Minneapolis, a city with a parks system much smaller than New York’s, the deferred maintenance need was $110 million in 2016.6

Since the 1970s fiscal crisis, the full-time staffing headcount of the Parks Department—including full-time and full-time-equivalent positions—has dropped from a high of 11,642 in 1976 to a little over 7,600, while shifting to a more seasonal workforce over time.7 Although staffing increased 11 percent between 2014 and 2016, nearly every

expert we interviewed says that maintenance staffing levels are insufficient for the aging system, especially amid unprecedented usage.8 “It’s always ‘do more with less,’ but you’re only going to be able to hit a certain point with that mindset,” says one senior DPR administrator. “It’s just not sustainable.”

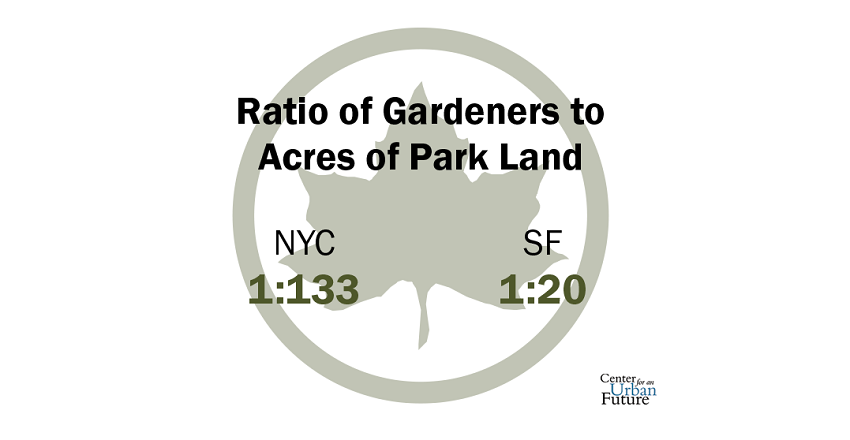

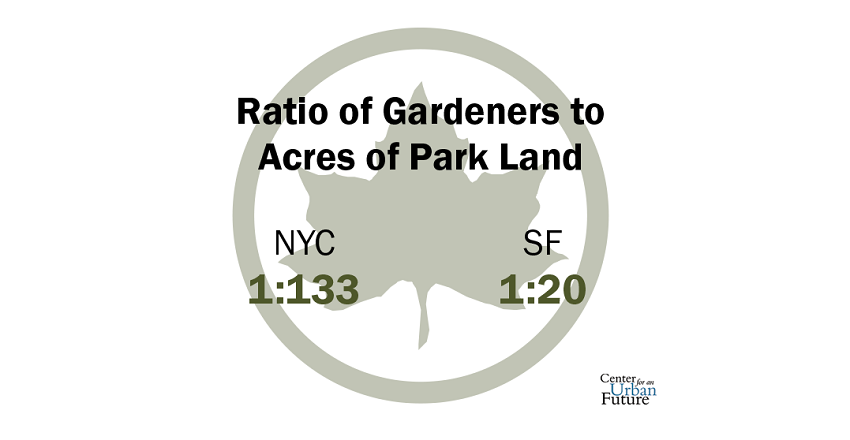

Insufficient maintenance funding means that New York’s parks system is dramatically understaffed when compared to other cities, with consequences for both day-to-day upkeep and the long-term health of its infrastructure. The result is that bathrooms go without water, drainage systems get blocked and cause flooding, walls deteriorate, and plantings and forests die. For instance, New York City has about 150 gardeners citywide for nearly 20,000 acres of parkland, not counting natural areas, and more than two million trees, a ratio of one gardener to every 133 acres—about one-quarter the size of Prospect Park. By comparison, the San Francisco Recreation and Parks Department has over 200 gardeners for 4,113 acres of parkland, a ratio of one gardener to 20 acres.9 (It should be noted that other staff support the work of gardeners in New York, including community park workers who focus specifically on horticulture.) Similar shortages exist for other skilled tradespeople, including plumbers, electricians, masons, carpenters, and marine mechanics. Some districts—like Bronx’s Community Board 8—have zero dedicated gardeners, although these areas are still serviced by mobile crews, while others have just one or two, which makes effective horticultural maintenance impossible. Parks surveyed in these communities were found to be in noticeably worse shape, with copious weeds and invasive plants and disheveled or dead plantings. In contrast, the Central Park Conservancy had a $52.3 million operating budget in FY 2016, including $8 million in city funding, and oversees a maintenance and operations team of 125 people for 840 acres, or one worker for every six acres. The High Line has a horticultural staff of 13, overseeing a little less than seven acres. Sustaining these world-class green spaces requires a level of maintenance staffing that the rest of the city’s parks sorely lack.

The Parks Department’s expense and state of good repair capital budgets have been chronically underfunded, weakening infrastructure and boosting long-term costs. Since parks are generally not hot-button campaign issues, like education or public safety, a number of sources say that the city’s parks have never received appropriate levels of funding—and the share of parks funding in the city budget declined steadily for four decades, before receiving a boost over the past four years. Without taking the cost of pensions, debt service, and fringe benefits into account, the Parks Department’s adopted expense budget for FY 2018 was $532 million, or 0.6 percent of the city’s overall budget of $87 billion that year—a share that has declined steadily from 1.32 percent in 1976.10 Under the de Blasio administration, however, that budget share has risen from 0.53 percent in FY 2014.

According to the Trust for Public Land’s 2017 ParkScore, New York spends less per capita on parks than other major metropolises that are a fraction of its size, a total of $178 per citizen, although this total does not take into account the cost of debt service, pensions, and fringe benefits. Highly rated Minneapolis spends $233 per capita; Washington, DC, spends $270.11 Even with 45.5 people per city acre, not including railways and airports—the highest population density of any major city in the United States—New York has low overall levels of parks funding that contribute to the system’s struggle to maintain its infrastructure.

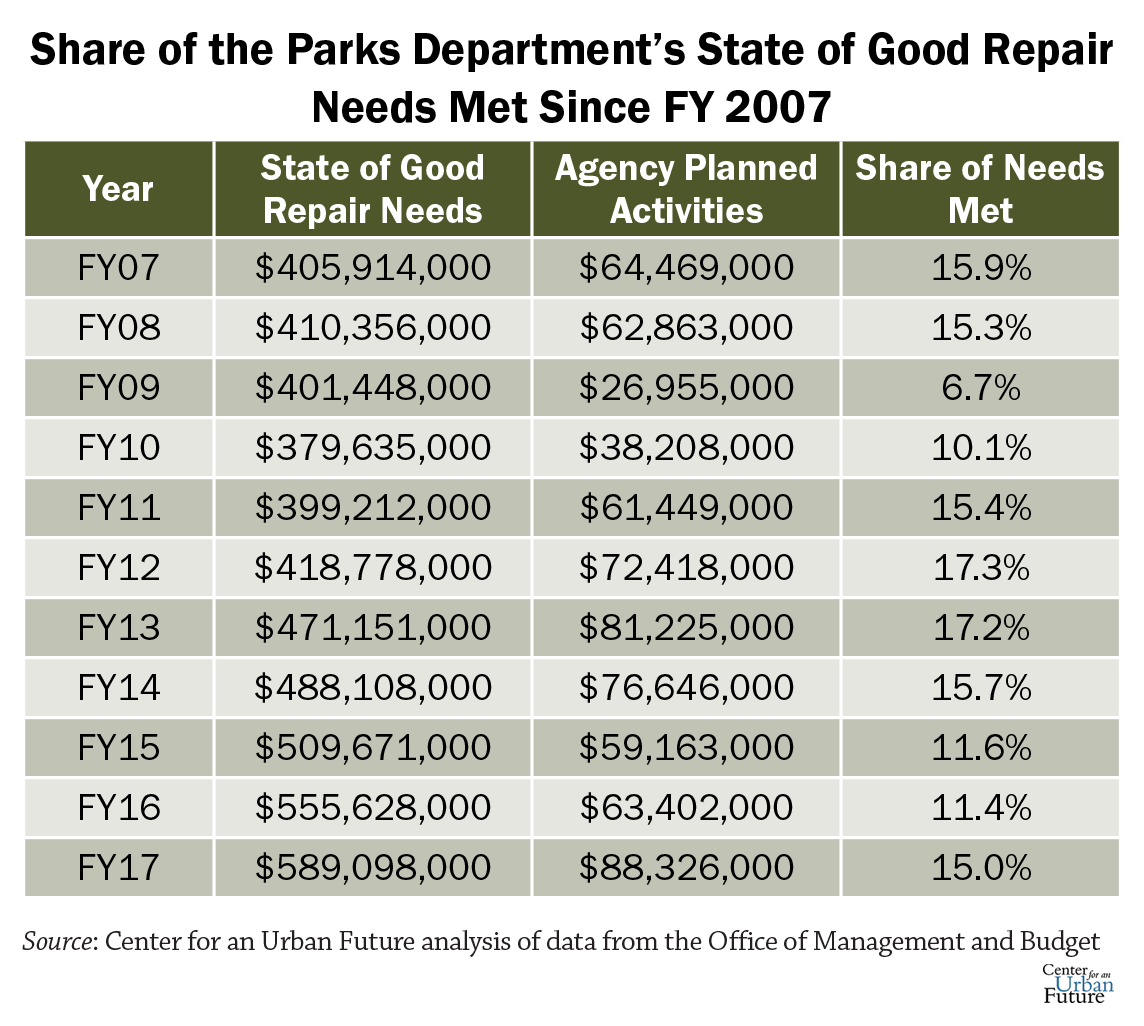

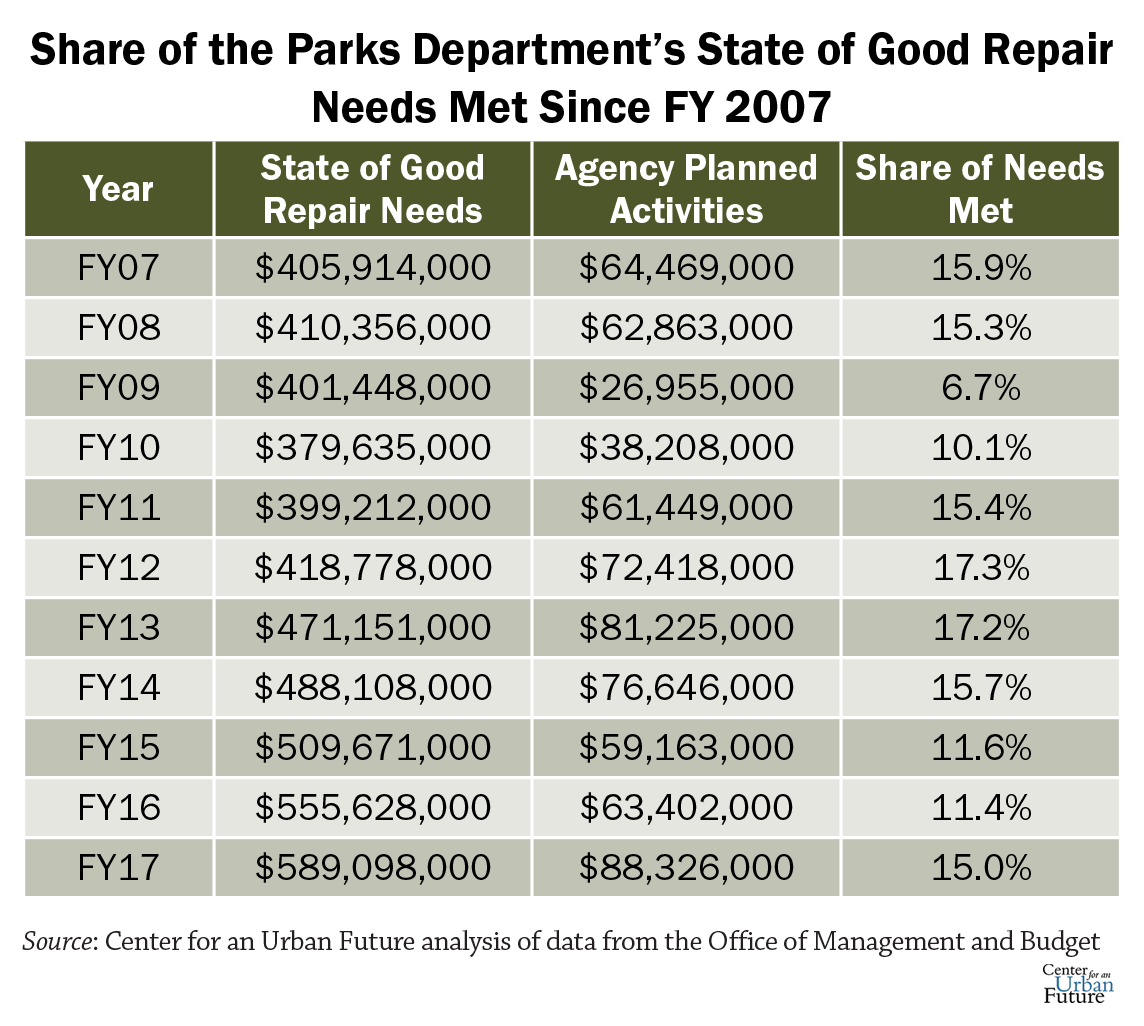

In FY 2017, the Parks Department was able to cover just 15 percent of its state of good repair needs, which was the second-lowest rate of any city agency, after the Brooklyn Public Library. The price tag of these infrastructure needs is also on the rise: in FY 2007, they totaled $405 million, according to the city’s AIMS reports, which detail the state of good repair needs for each agency over the following three years. By FY 2017, the cost had risen to more than $589 million—a 45 percent increase. This lack of funding means that many of the city’s parks wait decades before receiving upgrades.

To target these forgotten parks, the de Blasio administration launched the Community Parks Initiative, which funds renovations on an annual basis for parks that are between .15 and five acres in size, are located in high density areas, and have not received at least $250,000 in capital investment between 1993 and 2014. This important initiative is the first citywide effort designed to invest specifically in parks that have gone chronically underfunded. But it can barely keep up: while 67 parks are currently undergoing improvements, as of the end of 2017, 215 parks were ultimately found eligible. Likewise, under Parks Without Borders—an initiative to improve access to green space—eight parks were chosen to receive $50 million in improvements. Yet 691 parks applied, reflecting the demand for these improvements citywide.12

Piecemeal funding for parks infrastructure discourages systematic investment in areas of greatest need. With a slim baseline budget for capital work and limited funding

through the community boards, the department’s capital budget is largely cobbled together through discretionary funding, allocated by 51 City Council members, five borough presidents, and the mayor. This system makes it challenging for the Parks Department to prioritize funding for the most urgent infrastructure needs. Instead, elected officials will typically fund projects that constituents are clamoring for, rather than the more low-profile infrastructure investments that parks sorely need. It is far more likely that discretionary funds will be put toward building a playground or dog run rather than shoring up a retaining wall or fixing underground drainage systems.

“How projects are funded is so important,” says Susan Donoghue of Prospect Park. “You’ve got capital dollars coming into parks from council members or elected officials, funding what they know their constituents want to see. They love the playgrounds, and they love comfort stations, but who’s going to want to fund drainage projects? It’s definitely not as glamorous, or sexy, and yet it’s so critical to the everyday maintenance of a park.”

The high cost of capital projects means that vital, largescale investments often require several elected officials to pool funds, an approach that delays essential park projects and hinders cost-effective planning. In a system that relies on elected officials for most parks funding, those representing districts with greater socioeconomic needs end up with lesser-funded parks, exacerbating inequities across the city’s parks system. According to an analysis of all capital work completed since 1996, District 1 in Manhattan (Financial District, Chinatown, and the Lower East Side) has received $134 million for 134 site-specific capital projects. By comparison, in Washington Heights’ District 10, parks capital spending amounts to just 12 percent of District 1’s total: less than $16 million for 43 capital projects over the past 20 years. In Queens, four council districts—which contain high density neighborhoods such as Elmhurst, Jackson Heights, and Jamaica—had a combined capital investment of less than $50 million, barely 40 percent of the money spent in Manhattan’s District 2 (Gramercy Park, Kips Bay, and East Village), which totaled close to $125 million.

The city lacks critical data to effectively, and efficiently, plan parks projects. A more systematic approach to maintaining parks infrastructure requires actionable data, but the city is only just beginning to make data collection a priority. As of this report’s publication, the Parks Department is finally undergoing its first-ever needs assessment, which will catalog the age and capital needs for 50 types of infrastructure in all city parks. So far, only four types—comfort stations, recreation centers, synthetic turf fields, and retaining walls—have been funded for analysis. At this rate, Parks Department officials say, it could take up to 20 years to finish the assessment—a lifetime when it comes to specific infrastructure categories. Until the process is complete, it remains nearly impossible to answer integral questions about the parks system’s needs.

Although this initial effort is a critical first step, other essential data collection efforts remain unfunded. For example, natural areas are only included in the Parks Inspection Program (PIP) where there are trails, leaving one third of the city’s parkland with only partial inspections, while a citywide horticultural mapping effort is still in the preliminary stage.

In addition, the city’s Assets Information Management System leaves out assets with a replacement cost of less than $10 million, and excludes “most equipment,” “landscaping or outdoor elements,” and “aesthetic considerations.” Every source interviewed for this report agrees that the $555 million total for FY 2016 seriously underestimates the true extent of the system’s needs, but there is no data available to provide a more complete estimate. As a result, one Parks Department official says AIMS is like “a drive-by estimation of costs.” The data deficit also makes it much more difficult for the Parks Department to advocate on behalf of specific parks and infrastructure needs, resulting in a system in which new facilities and visible improvements are far more likely to receive funding than fixes to invisible infrastructure or preventative maintenance.

“DPR staff are not drivers of the process—they need to be able to say to elected officials the minute they’re elected, ‘Here are your problems, and here is what we need to do to fix them,’” says Denise Richardson, executive director of the General Contractors Association, whose members often work on parks projects. “Right now, that doesn’t happen, but that’s what parks need.”

Insufficient inter-agency coordination prevents systematic planning and cost-sharing. Jurisdiction in parkland is often hazy. No one city agency coordinates waterfront reconstruction, for example, and where responsibilities fall between the Parks Department and other departments, namely DOT and the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), is often unclear. This

interagency “rigmarole,” as one Bronx park administrator describes it, significantly delays the repair of crucial parks infrastructure. “Even though DOT maintains the roads, and DEP maintains the storm sewers and hydrants,” she says, “when it comes down to something like leaks on the roadways—who’s going to pay for it, and who’s going to fix the leaks—it can become very problematic.”

For example, the role of overseeing park bridges raises significant questions. Although DOT is technically tasked with their inspection, superficial upkeep is left to the Parks Department; in many cases, administrators have been left unclear regarding who is responsible. Catch basins in parks were once cleared by DEP, an agency with deep experience in water management. In recent years, the Parks Department has been charged with clearing them, despite lacking the capacity to handle the demand. Park advocates and administrators say that better coordination among agencies could expedite infrastructure repair projects and find more efficient ways to handle recurring maintenance needs.

The cumbersome capital process for parks projects leads to high costs and delayed fixes. The capital process for parks projects has earned a reputation among elected officials and residents as especially time-consuming and frustrating. On average, parks capital projects cost more and take longer than similar public-private partnerships.

For example, the Trust for Public Land, which has built more than 186 playgrounds in New York City public schools, reports that its costs are roughly half what the Parks Department pays. At a time when mounting needs and declining revenues mean capital dollars need to stretch as far as possible, the high costs of parks capital projects present a major obstacle to infrastructure improvement. In addition, extremely long timelines cause public consternation and frustrate elected officials, leading some to question the viability of funding parks projects.

“I have to question the logic,” says Council Member Andrew Cohen of the Bronx, “when projects I funded at the very beginning of my first term still haven’t seen a shovel in the ground.” For example, the process to build a single comfort station in Harlem’s Marcus Garvey Park, at a cost of $3.2 million with four different funders, started in March of 2015, and is projected to conclude in January 2019.13 A similar project in Brooklyn took seven years and $2 million to build.14 According to a New York Daily News investigation, the Parks Department had 43 projects delayed for five or more years in 2017.15

The capital process for parks projects is highly circuitous, with at least seven different agencies and offices reviewing various elements of each project, including a number of time-intensive approvals from the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). In most cases, these problems are not unique to the parks system, but reflect deeper issues with the city’s capital process overall, although officials report particular frustrations with the slow pace of many parks projects. Under the leadership of Commissioner Mitchell Silver, the Parks Department is making improvements to the capital process, shaving several months off the design and construction phases for newly initiated projects and mandating additional pre-construction testing to head off deeper changes down the road. But these efforts will have to go much further in order to significantly speed up the process and control skyrocketing costs.16

Although the needs may appear daunting, revitalizing New York City’s public parks infrastructure will be essential to the city’s future. “Parks, in and of themselves, are vital infrastructure,” says Commissioner Silver. “Parks are the first line of defense in New York’s resiliency efforts. They are increasingly used for stormwater retention, as tides rise. And they are now home to transit networks that are connecting the city.”

Parks Initiative and Anchor Parks Initiative have placed renewed emphasis on parks equity, investing in infrastructure improvements across all five boroughs. Between 2014 and 2016, the Parks Department’s expense budget increased by 16.4 percent, and its focus has largely shifted from building new parkland—which remains integral for the city’s healthy development—to much needed state of good repair spending, infrastructure planning, and maintenance. Voluntary commitments made by conservancies to provide maintenance in lesser-funded parks are also positive steps in balancing the playing field.

The city’s ten-year capital strategy for parks in FY 2019 is also the largest in the agency’s history, allocating $4.6 billion for parks, or $460 million per year. Meanwhile, the parks system’s state of good repair estimate—the funds necessary to bring its assets up to par—is $589 million for the next three years. Yet this report finds that both amounts fall short of the full scope of needs. We estimate that bringing the parks system up to a state of good repair would cost at least $5.8 billion over the next decade, or nearly $580 million a year; this figure only includes estimates of the repair and renovation costs to upgrade existing infrastructure, rather than including projected costs for any new additions.

“New York City was blessed with having a tremendous program of construction during the Works Progress Administration,” says Adrian Benepe, former Parks Department commissioner under Mayor Michael Bloomberg and senior vice president at the Trust for Public Land. “But all of those structures—bridges, highways, parks, pools—they’re all nearing the end of their natural life. So I’d say a very, very big bill is coming due, in the billions."

Renewing the health of New York’s parks will require an unprecedented commitment from city policymakers to build a system that is prepared for the next century of increasing use. “There’s a philosophical shift that needs to take place, where parks are seen as critical city infrastructure,” says Lynn Kelly, executive director of New Yorkers for Parks, and former president of Snug Harbor Cultural Center & Botanical Garden, on Staten Island. “Just as sewers and electrical lines are maintained, parks and open space should have equal weight in how they are funded and maintained.”

This report documents the most pressing infrastructure and maintenance needs facing the parks system today, examines best practices in cities nationwide—including Minneapolis-St. Paul, Chicago, and Philadelphia—and puts forward new approaches to planning, revenue sharing, and interagency coordination. The report concludes with a host of practical and achievable recommendations to maintain and improve New York City’s public parks, including options for new revenue sources to fund parks improvements, ideas for better maintaining and upgrading existing infrastructure, and investments in sustainable green infrastructure careers like public horticulture and stormwater management. Taken together, these findings document the challenges facing the parks system and form a blueprint for revitalizing New York City’s public parks infrastructure.

1. These findings are based on the Center for an Urban Future’s analysis of the only available data, which includes historical information collected on the Parks Department’s website and records of capital work dating back to 1996. Taken together, these sources provide information on the majority of parks in the system, although gaps remain due to the lack of accessible records prior to 1996. The capital work records were provided under a Freedom of Information Law request and covered the period from January 1996 to September 2017.

2. DOT, “2016 Bridges and Tunnels Annual Condition Report,” http://www.nyc.gov/html/dot/downloads/pdf/ dot_bridgereport16_part3.pdf.

3. NYC Parks, “History of Recreation in Parks,” https://www.nycgovparks.org/about/history/recreation.

4. NYC Parks, “History of Parks’ Swimming Pools,” https://www.nycgovparks.org/about/history/pools.

5. OMB, “AIMS Agency Reconciliation, FY 2016,” http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/as06-16.pdf.

6. Mark Andrew and Carol Baker, “Minneapolis Park Funding: Take the 20-Year City Hall Plan,” Minneapolis Star-Tribune, http://www.startribune.com/minneapolis-park-funding-take-the-20-year-city-hall-plan/376798801/.

7. Center for an Urban Future analysis of New York City 1975–1976 Modified Expense Budget, accessed from the Municipal Library.

8. NYC Parks, “Report on Progress: 2014–2016,” https://www.nycgovparks.org/downloads/nyc-parks-report-on-progress_2014-2016.pdf

9. San Francisco Recreation and Parks Department, “Public Budget Presentation (FY 2017–2018)” http://sfrecpark.org/wp-content/uploads/Public-Budget-Presentation.pdf.

10. Center for an Urban Future analysis of New York City 1975–1976 Modified Expense Budget.

11. The Trust for Public Land, “City Parks Fact Report 2017,” https://www.tpl.org/sites/default/files/files_upload/CityParkFacts_2017.4_7_17.FIN_.LO_.pdf.

12. NYC Parks, “Parks Without Borders,” https://www.nycgovparks.org/planning-and-building/planning/parkswithout-borders. Although only eight parks were selected to receive full funding as part of the Parks Without Borders initiative, the Parks Department is working to apply these

design concepts to parks citywide.

13. Stephon Johnson, “Comfort Station Providing Little Comfort for Harlem Residents,” Amsterdam News, August 3, 2017, http://amsterdamnews.com/news/2017/aug/03/.

14. “City Projects Should Not Take Forever and a Day,” Crain’s New York Business, June 27, 2017, http://www. crainsnewyork.com/article/20170627/POLITICS/170629910/editorial-city-projects-should-nottake-forever-and-a-day.

15. Denis Slattery, Joe Murphy, and Reuven Blau, “NYC Parks Dept. Has 43 Projects Like Playground Bathroom Delayed for Five Years or More; Stadiums, Bridges Were Built Faster,” New York Daily News, http://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/nyc-parks-dept-43-projects-stalled-5-years-article-1.3093135.

16. Amanda Mikelberg, “City Council Members Blister Parks Department for ‘Unacceptable’ Project Delays,” Metro, January 24, 2017, http://www.metro.us/new-york/citygrills-parks-department-for-unacceptable-project-delays/zsJqax---v7cnFs1hMSIg.

Photo Credit: John Surico

Problems exacerbated by the age of the parks system are compounded by deferred maintenance and a lack of infrastructure upgrades, which means that aging parks often go decades without significant investment in both aboveground and below-grade infrastructure. Based on this report’s analysis of historical records and capital projects data from the Parks Department, a city park saw its last major renovation, on average, in 1997. Citywide, 20 percent of parks have not undergone a major infrastructure upgrade in 25 years. That share is even higher for smaller parks: 34 percent of parks under one acre have gone at least two decades without significant capital work. Overall, at least 46 parks, triangles, and plazas in New York have not received significant capital investment in nearly a century. At least 5 of Brooklyn’s 411 parks saw their last major renovation in the 1980s. Nearly 70 percent of the parks in that borough were last renovated before 2000, while at least 39 Brooklyn parks haven’t received major capital work since opening, according to our analysis of the only available data—in eight cases, over 100 years ago. Queens has a total of at least 37 parks that are long overdue for revitalization, including at least six that haven’t undergone a major renovation for over 100 years, and 31 for over 50 years. Manhattan has at least six parks that haven’t been upgraded significantly in more than 100 years, and at least nine for over 50 years. Staten Island has at least seven parks that haven’t received any major upgrades for over 50 years.

Problems exacerbated by the age of the parks system are compounded by deferred maintenance and a lack of infrastructure upgrades, which means that aging parks often go decades without significant investment in both aboveground and below-grade infrastructure. Based on this report’s analysis of historical records and capital projects data from the Parks Department, a city park saw its last major renovation, on average, in 1997. Citywide, 20 percent of parks have not undergone a major infrastructure upgrade in 25 years. That share is even higher for smaller parks: 34 percent of parks under one acre have gone at least two decades without significant capital work. Overall, at least 46 parks, triangles, and plazas in New York have not received significant capital investment in nearly a century. At least 5 of Brooklyn’s 411 parks saw their last major renovation in the 1980s. Nearly 70 percent of the parks in that borough were last renovated before 2000, while at least 39 Brooklyn parks haven’t received major capital work since opening, according to our analysis of the only available data—in eight cases, over 100 years ago. Queens has a total of at least 37 parks that are long overdue for revitalization, including at least six that haven’t undergone a major renovation for over 100 years, and 31 for over 50 years. Manhattan has at least six parks that haven’t been upgraded significantly in more than 100 years, and at least nine for over 50 years. Staten Island has at least seven parks that haven’t received any major upgrades for over 50 years.