In the years ahead, New York will need to address a number of profound social, demographic and economic challenges—including a fast growing elderly population, an increasing immigrant population without the English skills to thrive and a large pool of people with limited educations at a time when employers in nearly every industry are demanding higher levels of literacy and digital proficiency. Few institutions are better positioned than the city’s public libraries to help the city meet these sorts of challenges. Unlike the vast majority of city agencies, libraries are embedded in nearly every neighborhood in New York and offer an uncommonly broad range of services. In addition, as more of the city’s future population and economic growth occurs outside of the city’s central business districts, libraries have the potential to be increasingly critical anchors for community and cultural development. Their physical presence in virtually every corner of the city makes them an important resource. And given societal trends such as the demise of book stores and the rise of freelancers, there may be a unique opportunity for some libraries to take on new roles in the economic, civic and social life of communities.

However, despite their growing importance, public libraries have been hugely undervalued by policymakers and are absent from most policy and planning discussions about the future of the city. Meanwhile, there has been insufficient thinking about the future sustainability of New York’s libraries at a time when public resources for these institutions are diminishing and growing numbers of New Yorkers are shunning printed books in favor of digital versions they can read on their iPad, Kindle or Nook.

“With over 200 branches across the city and only enough funding for them to stay open 40 hours a week, there’s a lot of infrastructure here going unused.”

Libraries offer more programs and circulate more materials than ever before, but these accomplishments have been achieved despite shrinking budgets and support from the city. Since 2008, NYPL has suffered a net $28.2 million reduction in city funds, while Brooklyn and Queens have absorbed cuts worth $18.1 million and $17.5 million respectively.

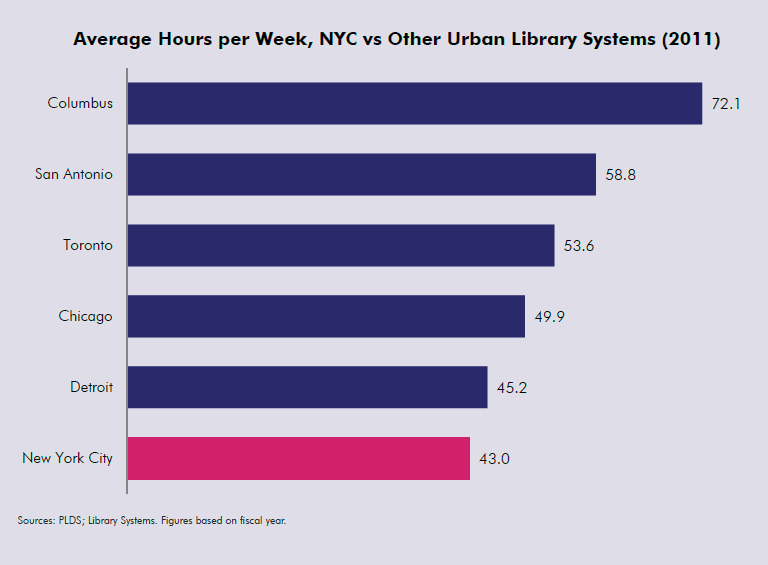

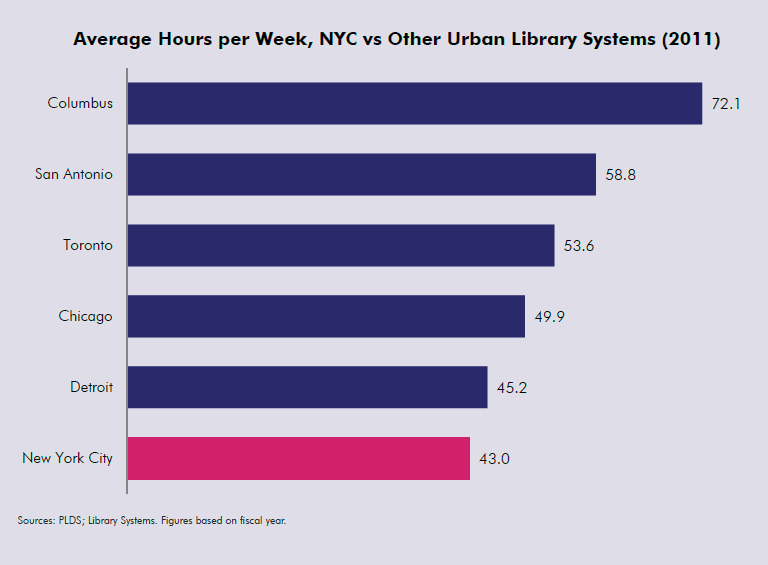

Due to these funding reductions, all three systems have had to reduce their hours of operation to an average of five days a week, down from six days a week in 2008. Even the Detroit public library system stays open longer. The three New York City public libraries are open 43 hours a week on average, compared to roughly 50 hours a week in Chicago and Boston, 55 in Toronto and 70 in Columbus.

The budget cuts have also forced the libraries in New York to curtail the amount they spend on books and other materials (QPL’s materials acquisition budget has dropped from $15 million to $5 million over the past few years) and to lay off staff (the three systems have reduced staff by 24 percent, on average, since 2008). In Queens, circulation is down by 10 percent since the cuts started in 2008, a major turnaround after circulation had increased by 36 percent between 2004 and 2008.

Every year since 2008, the libraries have also had to fight off much larger proposed budget cuts during what has become an annual “budget dance,” with the mayor proposing a huge reduction to libraries and the City Council restoring much of the funding. Although the vast majority of these proposed reductions were eventually restored when the official city budget was enacted, the process has severely hampered the libraries’ ability to plan for the future and invest in innovative new services.

For this report, we asked the libraries what a modest increase in operating support would allow them to do. By the libraries’ own calculations, an additional $50 million a year in city operating funds would allow all three systems to stay open an average of 50 hours a week. And because more people would then be able to access their resources and services, they estimate that circulation would increase by an estimated 10 million materials and their program attendance by 500,000 people.8 An increase of $100 million in city funds would allow the libraries to stay open an average of 60 hours per week and put them in position to become the most utilized libraries in the country, if not the world.

“With over 200 branches across the city and only enough funding for them to stay open 40 hours a week, there’s a lot of infrastructure here going unused,” says Queens president Tom Galante.

However, a lack of operating funds is not the only financial challenge facing libraries. Because of the way capital projects are funded, dozens of branches across the five boroughs are confronting what more than one person in our interviews called “a maintenance crisis.” The Brooklyn system currently faces over $230 million in deferred maintenance costs, including $8 million at a single branch in northern Brooklyn, according to Josh Nachowitz, the Brooklyn Public Library’s vice president of government affairs. Even as several branches citywide—from the new Jamaica Central Branch to the Bronx Library Center—have undergone much-needed renovations in recent years, a number remain in bad shape. “The Bronx Library Center is beautiful, but the local [branches] are struggling,” says one Bronx-based community leader. “They are short of books, look dull and dreary, and lack programming.”

We heard similar anecdotes in every borough, a major problem for the libraries since our research suggests there is a strong correlation between the condition of branches and the number of people using them.

As we detail in this report, Brooklyn has fallen far behind the other two systems in total capital funding. Of committed funds—a term city officials use to designate dollars spent rather than simply budgeted for a future project—NYPL raised $215 million between Fiscal Year 2003 and Fiscal Year 2012; and Queens raised $153 million during that time, while Brooklyn only brought in $101 million.9 Taking into account the relative population sizes of their service areas, that comes to $62.41 per person for NYPL, $68.79 per person for Queens and just $40.50 per person for Brooklyn. When broken down by borough, branches located in Brooklyn and Staten Island have raised much less in capital funds than branches located in Queens, the Bronx and Manhattan. Staten Island branches have raised only $6 million in funds in the last ten years, compared to $97 million for Manhattan branches and $107 million for Bronx branches.

The libraries could also use additional funds and more financial security to address gaps in service and to make investments in technology that would help them stay relevant in an age where people are increasingly reading books digitally.

Libraries in several neighborhoods with high levels of unemployment, high school dropouts and chronic illness often are underutilized by their communities. For example, the Red Hook, Brownsville, Stone Avenue and Walt Whitman branches in Brooklyn have struggled for years to attract patrons. In northern Manhattan, the 125th Street branch on the far east side remains badly underutilized, while in the South Bronx, Woodstock and West Farms have maintained relatively low circulation numbers for years. Many of these branches are physically isolated, far from commercial districts. Safety also is often a big concern, as in Brownsville, where the main branch is far from the closest commercial center.

Next, public libraries currently can serve only a tiny fraction of the people who come to them for ESOL and pre-GED training. Because libraries aren’t eligible for the vast majority of state funding for adult literacy courses, they can afford to serve only 7,000 students citywide every year, despite long waiting lists for these services and having the physical space for at least double that number. Katherine Perry, director of adult literacy at the Flushing branch in Queens, says that the demand for ESOL in the neighborhood is so overwhelming that only 20 percent of the people on the library’s wait list end up getting a spot.

Another big challenge facing libraries is the need to build a virtual environment—and business model—to support the lending of electronic materials over the Internet, including e-books and audio files. Although almost everyone seems to agree that e-books are the wave of the future, many major book publishers have put up roadblocks to e-lending. Not only do e-books cost libraries considerably more than hardbacks or paperbacks, some publishers like HarperCollins only allow 26 checkouts for every e-book purchase, forcing the libraries to buy those books again when the limit is reached. Other publishers like Macmillan and Simon and Schuster won’t sell e-books to libraries at all. Because checking out an e-book is so much easier than checking out a physical book—patrons can do it at any time of day without leaving the comfort of their home—publishers are worried the libraries will “cannibalize” sales.

Yet all three library systems have been marching ahead anyway. Between January 2011 and January 2012, e-book checkouts across all three systems rose 179 percent. The libraries have added new e-book platforms like the Amazon Kindle and a bunch of new titles, and have been working with the technology company Overdrive to build out their websites with more interactive capabilities and suggestion engines like those on Netflix or Amazon. Still, the three systems have a long way to go before e-lending becomes the norm. In NYPL’s case, electronic checkouts account for only 5.5 percent of total circulation, and at both Brooklyn and Queens they constitute less than 1 percent of the total.

Beyond innovating in the digital realm, libraries have been examining new library typologies, mainly smaller, more flexible spaces in storefronts in busy commercial districts or transportation hubs such as Grand Central Terminal or JFK airport. They also have been looking at new partnerships and programming possibilities, such as turning some of the underutilized space in struggling branches into incubators for artists. But, because of funding constraints, the systems have barely begun to scratch the surface of possibilities.

For this report, we spoke to a number of designers, architects and technologists to discuss how libraries might change for the better over the next few years, and we came up with a long list of tantalizing possibilities. For example, many of the innovators we spoke to said that the potential for new, neighborhood appropriate partnerships has never been greater in New York. Arts groups like Spaceworks, chashama and 3rd Ward are renovating underutilized spaces for art shows and workshare spaces. Non-profits like 826NYC are running successful storefronts that double as shops selling quirky, genre-inspired merchandise and locations for afterschool mentoring and tutoring. As one designer told us, there is no reason libraries can’t build “super hero shops” or “pirate shops,” as 826NYC has done in Brooklyn and Pittsburgh respectively, on the ground floors of select library branches and work with these groups’ extensive volunteer networks to put on creative writing programs for school children. Or how about partnering with Facebook, Google, Tumblr or one of the other tech companies in New York to build a library-based tech center that would provide access to new gadgets and basic software classes?

Absent a partnership, libraries could learn a lot from the Apple Store or, indeed, from many other private sector retailers and service providers. The bright sight lines in those stores, for example, create a sense of openness and dynamism. “You enter and you don’t feel like there’s a list of rules you have to decode,” says Albert Lee at the design firm IDEO. Moreover, with enough support to cover major upgrades, libraries could begin to tap new revenue possibilities. Library websites attract millions of visitors a month. If they could perfect an online browsing environment with recommendations and interactive capabilities, libraries could sell advertisements and user data like any other digital media company. Knowing how a user landed on a particular book, for example, could be extremely valuable to publishers.

Libraries are without question at a crossroads. The business of making and distributing books is undergoing a tremendous upheaval as the Internet matures. At the same time libraries are experiencing an historic resurgence as community centers at exactly the same time that government support for them is waning. Circulation is at historic highs despite dwindling book budgets, and the number of programs on offer is greater and more diverse than ever before, even as staff levels have plateaued. This is a huge lost opportunity for New York. If libraries are going to fulfill their potential as engines of upward mobility and take advantage of opportunities afforded by the Internet, they will need far greater financial and institutional support than they have received so far.

This is an excerpt. Click here to read the full report (PDF).