The following is the introduction to Creative New York.

Read the full report (PDF).

View the recommendations from the report.

View the charts and tables from the report.

Ten years ago, the Center for an Urban Future published Creative New York, the first comprehensive report documenting the economic impact of New York City’s nonprofit arts organizations and for-profit creative businesses. In the decade since we published that 2005 report, much has changed in New York’s creative landscape.

Sharp increases in city capital funding and private philanthropy and a record rise in tourism have spurred major expansions of museums and theaters. New creative clusters have emerged in neighborhoods across the five boroughs. Technological changes have created new challenges for traditional creative industries like publishing and music production, while online platforms such as Kickstarter and Etsy are offering new opportunities for working artists and nonprofits. Skyrocketing rents have forced numerous music venues, nonprofit theaters and art galleries to close their doors and made it difficult for many of the city’s artists, architects and other creative workers to afford to remain in the city.

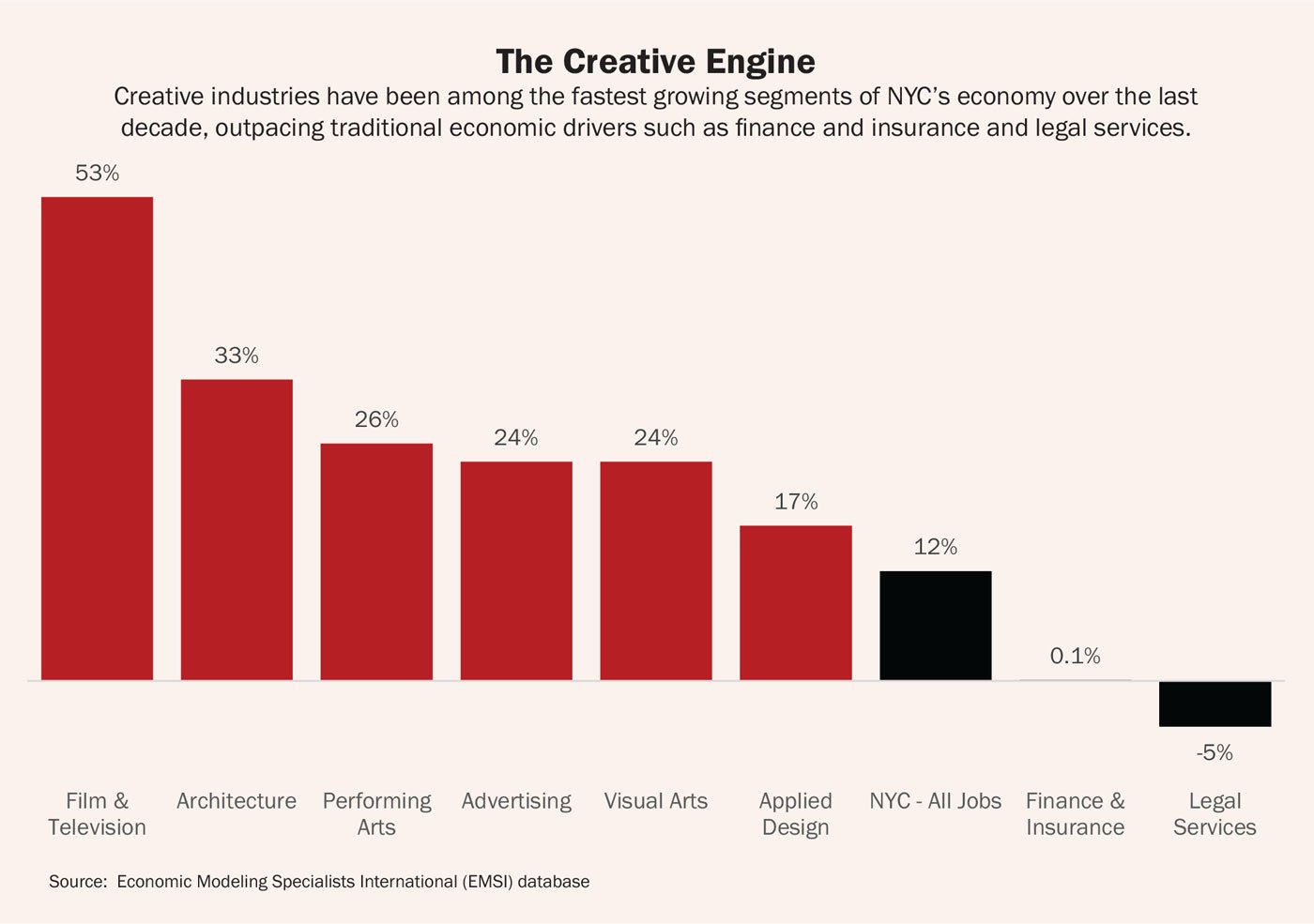

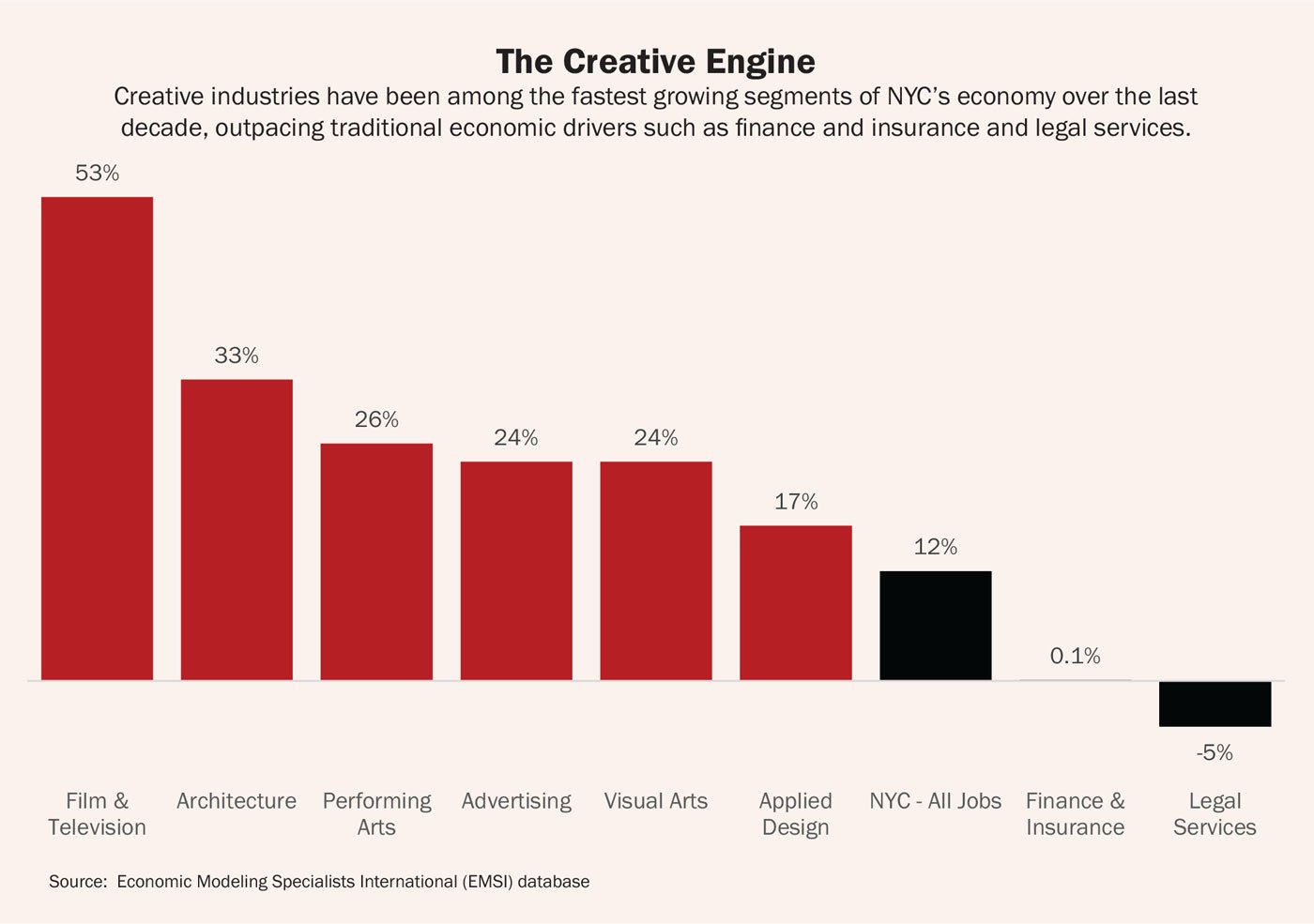

But as much as things have changed, the arts and the broader creative sector have only become more critical to New York City. While traditional economic drivers like finance and legal services have stagnated in recent years, several creative industries have been among the fastest growing segments of the city’s economy. Employment in film and television production soared by 53 percent over the past decade, while architecture (33 percent), performing arts (26 percent), advertising (24 percent), visual arts (24 percent) and applied design (17 percent) all outpaced the city’s overall employment growth (12 percent).

Overall, New York City’s creative sector—which by our definition includes ten industries: advertising, film and television, broadcasting, publishing, architecture, design, music, visual arts, performing arts and independent artists—employed 295,755 people in 2013, seven percent of all jobs in the city. Employment in the sector is up from 260,770 in 2003, a 13 percent jump. Meanwhile, the city is now home to 14,145 creative businesses and nonprofits, up from 11,955 a decade ago (18 percent increase).

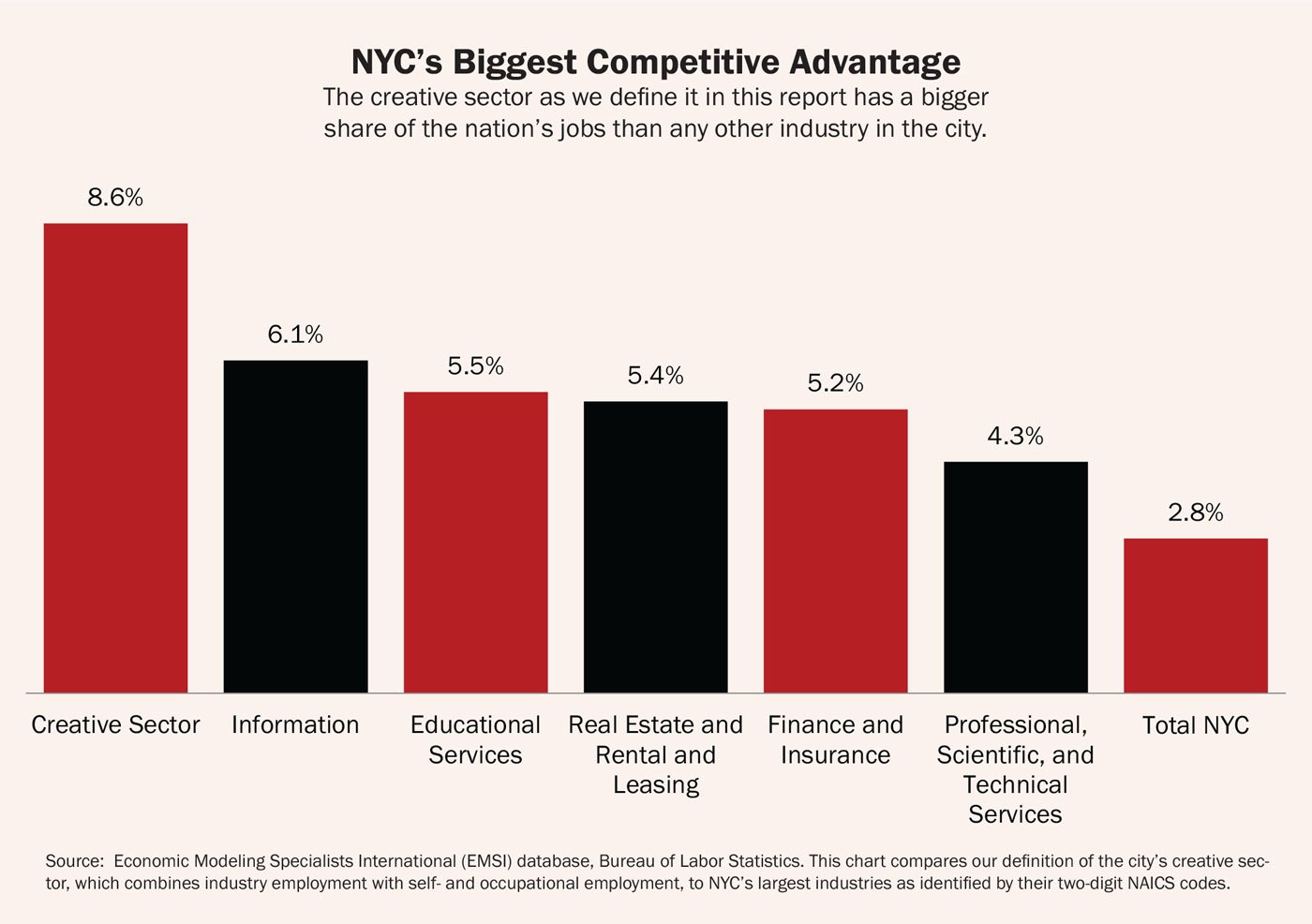

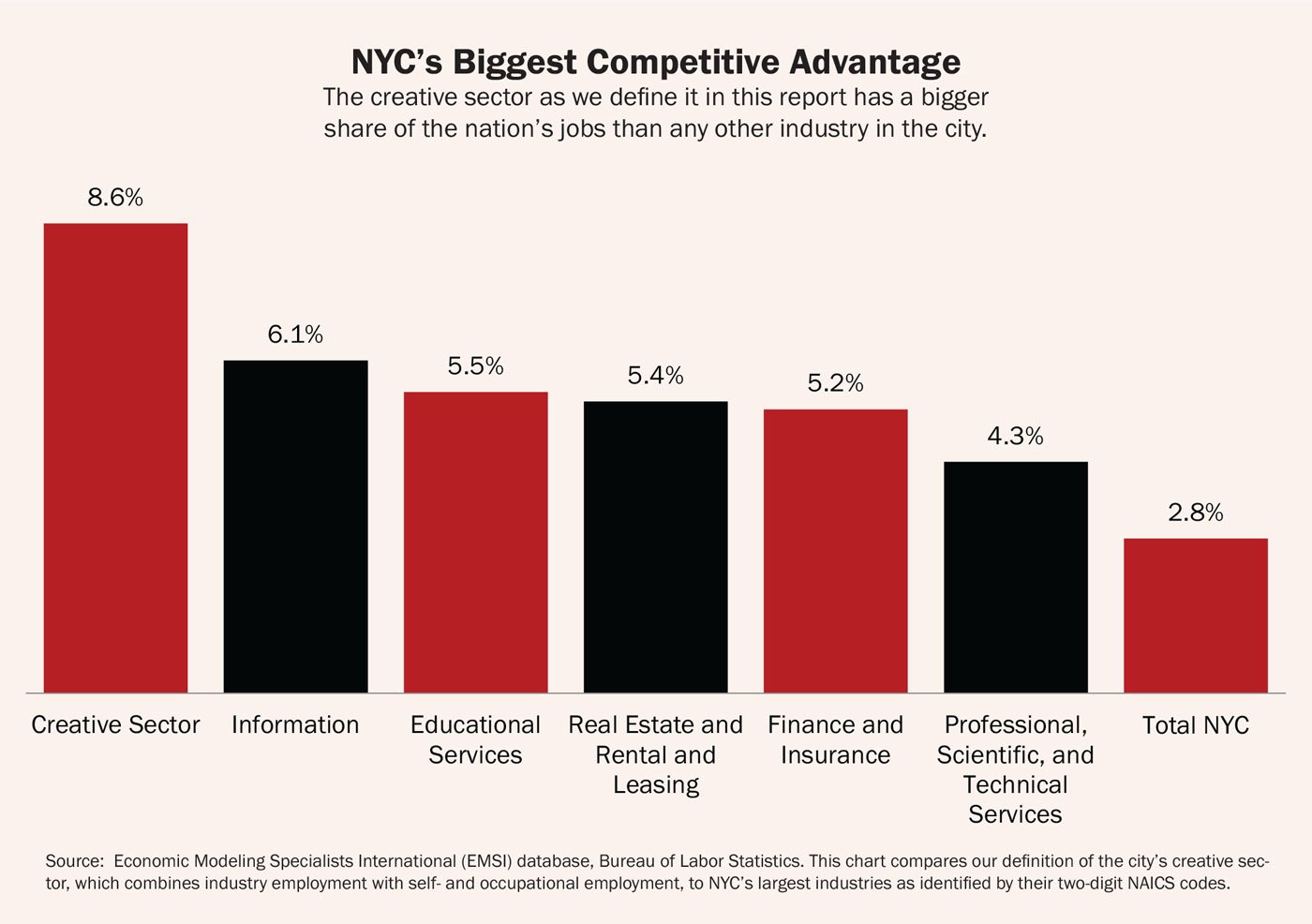

Although the tech sector has grown more rapidly in recent years, and industries such as healthcare and retail have more jobs overall, the creative sector arguably provides New York with its greatest competitive advantage. In 2013, New York City was home to 8.6 percent of all creative sector jobs in the nation, up from 7.1 percent in 2003. Of the city’s 20 largest industries, none comprise a larger share of the nation’s total jobs, including information (which accounts for 6.1 percent of national jobs), educational services (5.5 percent), real estate (5.4 percent) and finance and insurance (5.2 percent).

While all this is cause for optimism, the continued growth of New York’s creative sector is by no means assured. As we detail in this report, working artists, nonprofit arts organizations and for-profit creative firms face more intense challenges than ever before. At the same time, a growing number of cities—from Shanghai and Berlin to Portland and Detroit—are aggressively cultivating their creative economies and posing a legitimate threat to the Big Apple.

Coming ten years after the publication of our 2005 Creative New York study, this report takes a fresh look at the role of the arts and the broader creative sector in New York’s economy, provides a detailed analysis of what has changed in the city’s creative landscape over the past decade and documents the most pressing challenges facing the city’s artists, nonprofit arts organizations and for-profit creative firms. The study was informed by interviews with more than 150 artists, writers, designers, filmmakers, architects and other creative professionals, as well as advocates, nonprofit administrators, donors and government officials. These firsthand accounts were supplemented with an analysis of Census, labor, tax and grant data in addition to a variety of surveys and research reports. In an important departure from other policy reports focusing on the arts—including the 2005 Creative New York study—we have also made a point to document the size and diversity of the arts in the city’s immigrant communities. The report, which was generously funded by New York Community Trust, Robert Sterling Clark Foundation, Laurie M. Tisch Illumination Fund, Rockefeller Brothers Fund and Edelman—culminates with a new set of recommendations for how policymakers, philanthropy and the private sector can strengthen the city’s nonprofit arts and for-profit creative sector.

For many in New York’s creative sector, the last decade has been marked by growing affordability challenges. Legendary musicians and writers like Patti Smith, David Byrne, Moby and Fran Lebowitz have expressed pessimism about the future of the arts in this city and have even encouraged younger artists to look elsewhere before moving here. “There is no room [in New York] for fresh creative types,” wrote David Byrne in a widely circulated 2013 opinion piece. “Middle-class people can barely afford to live here anymore, so forget about emerging artists, musicians, actors, dancers, writers, journalists and small business people.”

These are valid concerns. Nearly all of the 150 people in the arts and creative industries who were interviewed for this report cited affordability as a major threat to the vitality of the arts in New York. And there are numerous examples of artists and arts organizations opting to leave the city. Yet, our conclusion is that it is far too soon to write New York’s obituary as a global creative capital.

Over the last decade, the city’s creative economy has grown impressively, outpacing both rival cities around the country as well as more traditional economic engines in New York, such as finance, insurance, real estate and legal services. For this report, we focused on both the traditional nonprofit arts and for-profit creative industries and combined several labor market sources to cover employees of creative organizations, self-employed creative workers and creative workers employed by organizations outside of the creative industries. While this allowed us to provide a more comprehensive picture of what many authors and analysts have called ‘the creative economy,’ our definition of that term (see methodology on pg. 13) is more conservative than most others and focuses on just a core of industries and occupations directly engaged in creative work.

Our analysis shows that the city’s creative workforce totaled 295,755 in 2013. This includes 216,110 workers employed at businesses and nonprofits in the ten industries that make up New York’s creative core (visual arts, performing arts, advertising, architecture, broadcasting, design, film and video, music and publishing, and independent artists), 46,255 self-employed workers in creative industries and 33,390 creative workers employed in non-creative industries. Overall, the city’s creative workforce is up 13 percent from 2003, when the total was 260,770.

Both nonprofit and for-profit commercial industries experienced significant growth during this period. Of the ten industries constituting New York’s creative core, six outpaced the city’s overall 12 percent employment growth: film and television (53 percent), architecture (33 percent), performing arts (26 percent), advertising (24 percent), visual arts (24 percent) and applied design (17 percent). Of the 25 creative occupational categories we examined—including dancers, directors, painters and make-up artists—15 experienced employment growth of 10 percent or more. For instance, the number of film and video editors in the city grew by 43 percent, architects 35 percent, actors 30 percent and curators 26 percent.

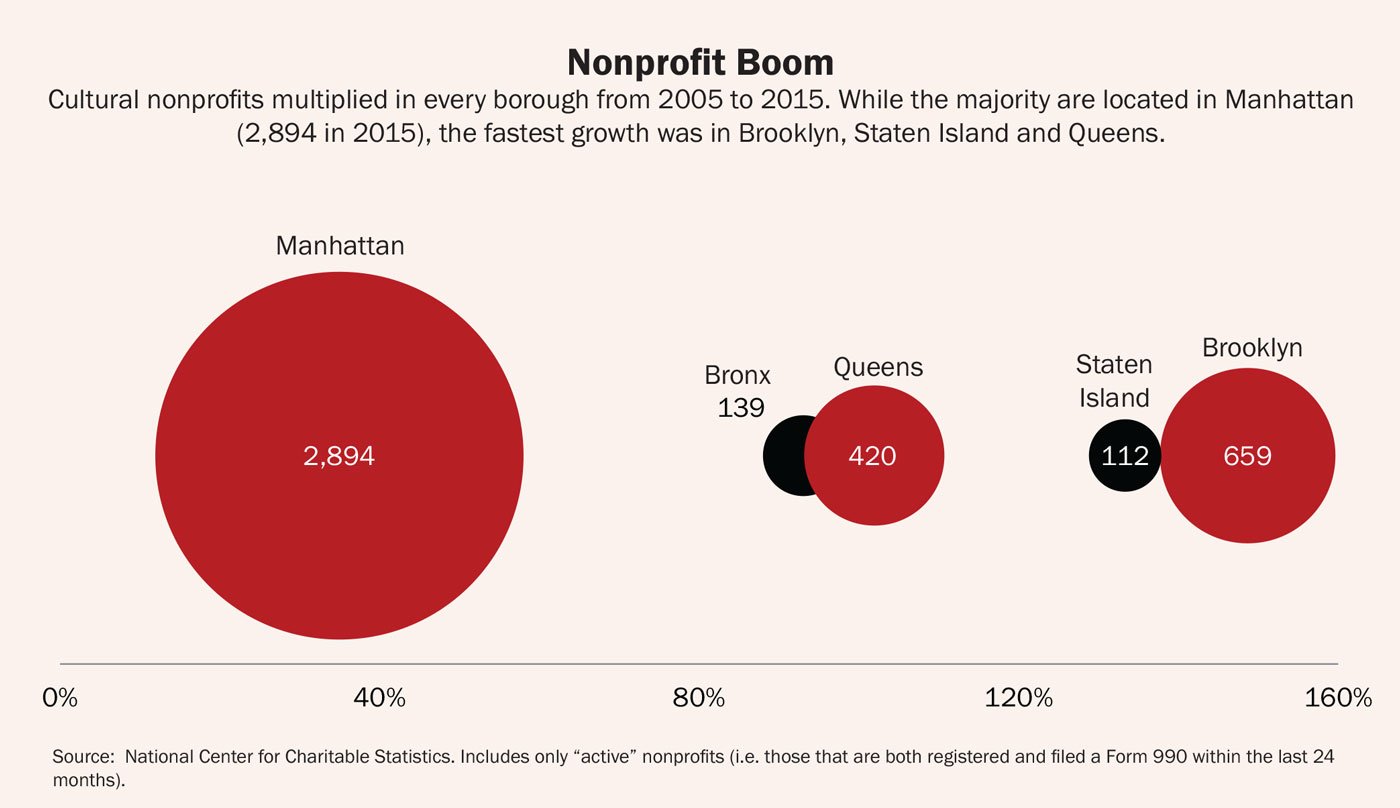

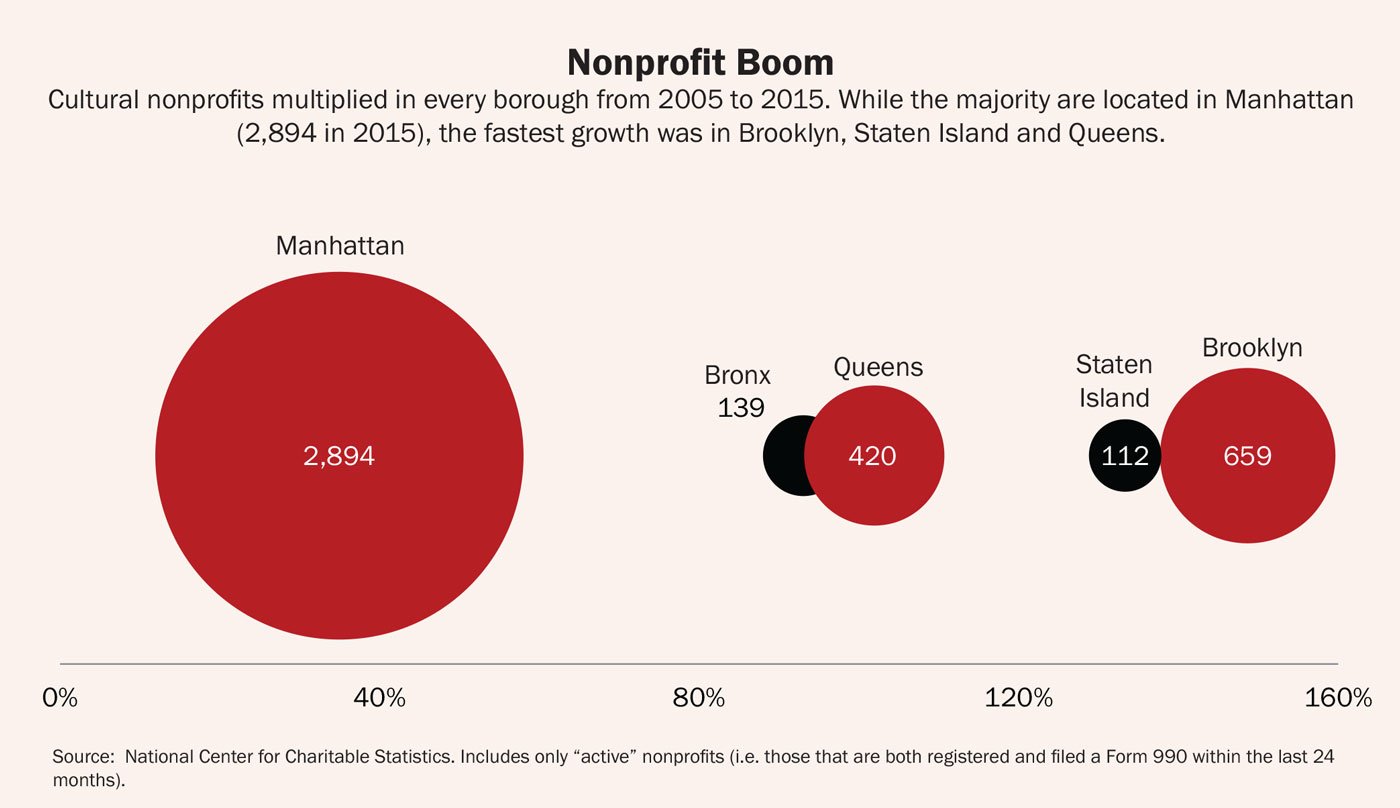

New York City has far and away more arts nonprofits than any other American city. In 2015, the five boroughs were home to 4,224 cultural nonprofits, versus 3,051 for L.A., 1,697 for Chicago, 1,068 for Washington, D.C. and 1,017 for Houston. The number of cultural organizations in New York City increased by 54 percent over the past decade.

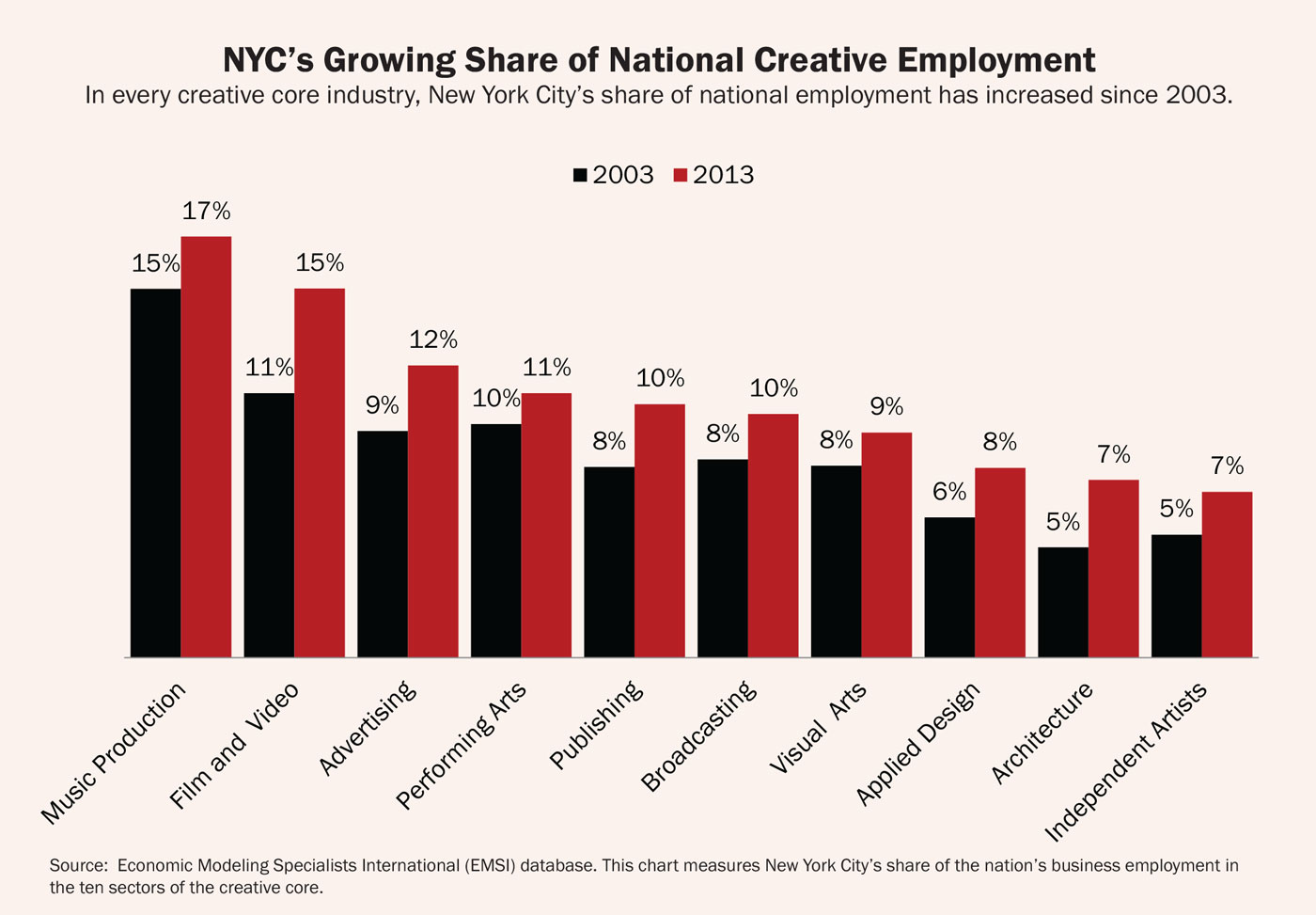

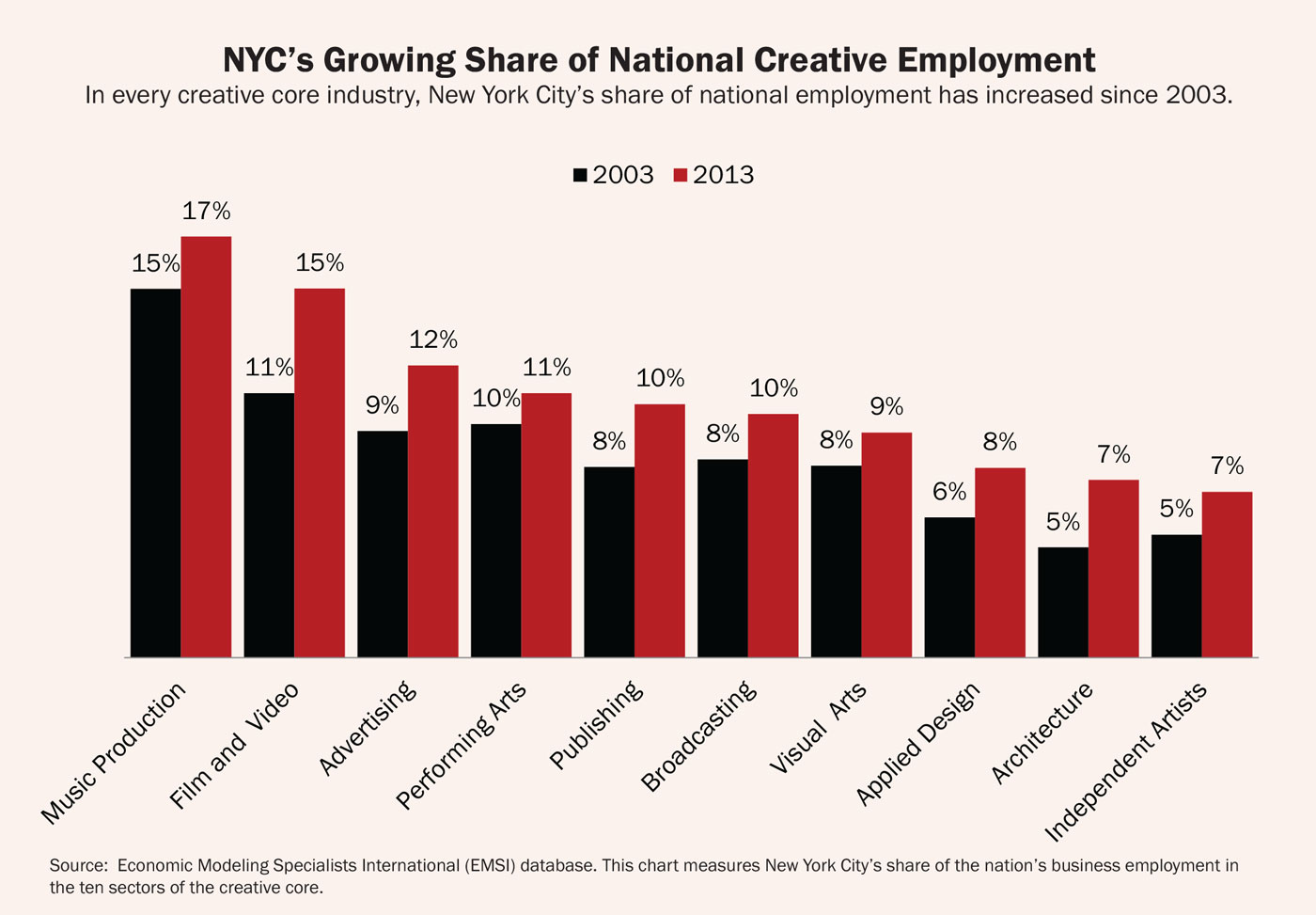

All of this growth has reinforced New York’s position as the nation’s creative capital. In 2003, 7.1 percent of the national creative workforce was centered in the Big Apple. By 2013, that share had grown to 8.6 percent, far higher than the city’s 3 percent share of all jobs in the nation. The five boroughs are now home to 28 percent of the country’s fashion designers, 14 percent of producers and directors, 12 percent of print and media editors and 12 percent of art directors. Amazingly, for every industry in the city’s creative core, New York City’s share of national jobs increased significantly from 2003 to 2013, including especially large jumps in film and television (11 percent to 15 percent), advertising (9 percent to 12 percent) and architecture (4.5 percent to 7.3 percent). Interestingly, the only two creative industries that experienced a decline in total jobs—publishing and music production—have seen an increase in the city’s share of national employment, with New York recently surpassing Los Angeles to become the largest music industry cluster in the nation.

We also examined growth in creative business employment—workers employed at businesses and nonprofits in ten industries that make up the creative core—for New York City and 17 other U.S. cities/counties where there are at least 10,000 creative workers. Of those cities, only Austin (40 percent) and Portland (22 percent) saw greater growth than New York (15 percent) over the last decade. While both those cities are now considered creative meccas, it is telling that the growth in New York’s creative business employment alone is 26 percent larger than the total creative business employment in both cities combined. For that matter, New York’s growth is 8 percent larger than the total creative business employment in San Francisco, another creative rival.

In the past decade, New York City also overtook Los Angeles County as the largest creative business cluster in the United States. In 2003, L.A.’s creative business employment totaled 207,293, compared to 188,033 for New York. But in 2013, New York’s total (216,110) exceeded L.A.’s (202,072).

And it’s not just employment and revenue that are growing. Whether it is film, fashion, theater, or architecture, many of those we interviewed described what could only be called a peak in the quality and diversity of productions. “Playwriting is in a golden age,” says André Bishop, producing artistic director at Lincoln Center Theater. “When I started out at Playwright Horizons in the mid-1970s, there might have been five theaters outside of Broadway that did new work. Now there are many, many theaters in New York devoted to new plays.”

In fashion, “the pool of talent in New York is bigger than it ever was, and more competitive,” says Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA) chief executive officer Steven Kolb. “There’s a pop culture status that never existed before.”

In the last ten years, 21 New Yorkers have won Pulitzer Prizes in poetry, fiction, music and drama.Of the 76 films nominated in the two documentary film categories (Short and Feature) between 2005 and 2012, 32 had a New York City-based director, and 35 had a producer based in the Big Apple. The number of gallery spaces jumped from 1,138 to 1,384 citywide, and from 95 to 248 in Brooklyn, between 2004 to 2015. Art and design festivals like Frieze, Fashion Week, the International Contemporary Furniture Fair and BKLYN Designs all host more shows and attract more attendees than ever before. New York’s film and television industry, once plagued by “runaway” productions—films set in New York but shot elsewhere—is now booming. From 2002 to 2011, total spending by film and television productions in the city nearly doubled, from $2.3 billion annually to $4.5 billion, and the number of television shows rose from 41 to 91.

The city is incubating new movements in street dance, fine art, site-specific immersive theater and storytelling—and cross-cultural, cross-disciplinary experimentation is as vital and omnipresent as ever. Four decades after its inception in the South Bronx and expansion across the globe, hip-hop has returned to New York to infiltrate fine art, high fashion and Broadway. Harlem-born rapper A$AP Rocky recently collaborated with Raf Simons, a top fashion designer, on a new clothing line. And Lin-Manuel Miranda’s In the Heights and Hamilton introduced hip-hop to musical theater while collecting critical acclaim and popular success.

The economic impact of all this innovation and growth is enormous. As creative workers multiply and experiment and their companies grow, they spend more on support services and suppliers. This benefits thousands of ancillary businesses across the city, including lumber, equipment and catering companies, as well as manufacturers producing everything from clothing to furniture.

New York’s creative industries are also the single biggest draw for tourists, and thus a critical catalyst for growth in the city’s hospitality sector. In the last dozen years, the number of tourists visiting the city rose 60 percent, from 35.3 million in 2002 to 56.4 million in 2014. Foreign visitors more than doubled, from 5.1 million annually to 12.2 million, and the number of tourists visiting cultural institutions rose from 19 million to nearly 25 million. Events like the biannual Fashion Week have attracted attendees from around the globe, generating $547 million in direct visitor spending and $887 million in total economic impact each year.

The city’s creative economy also drives growth in the tech sector. Tech entrepreneurs not only draw from the city’s designers, photographers, authors and editors, but actually build on existing services in the creative fields, whether fashion (Warby Parker, Gilt Group), media (Buzzfeed, Vice) or advertising (AppNexus, Doubleclick). Though Etsy and Kickstarter, two rapidly growing platforms for selling and fundraising respectively, serve creative professionals working in cities around the world, New York-based artists and designers have done the most to prove the value of these new tools. A disproportionate share of the transactions on both sites has benefited New York-based artists and creative workers. Of all the money raised on Kickstarter, 14 percent—or $105 million over six years—has gone to New York City-based projects. This includes 32 percent of all funding in dance, 25 percent in theater, 20 percent in fashion and 19 percent in photography. Meanwhile, there are more Etsy sellers from New York City than yellow cab drivers.

“Our core competitive advantage as a city is our ability to exploit the economics of creativity,” says John Alschuler, chairman of HR&A Advisors, an economic development and real estate consulting firm. “Creativity in all kinds of different sectors is what drives New York.”

The arts and the broader creative economy has also provided a significant boost to many city neighborhoods, from Bushwick and Gowanus to Hudson Square and Long Island City. “The role the arts play in defining the urban landscape in New York is considerable,” confirms Karen Brooks Hopkins, the long-serving president of the Brooklyn Academy of Music, who recently stepped down. “Arts employ thousands. Arts are the biggest tourist spend. Arts provide incredible educational resources. Arts build community. It’s a powerful and positive tool.”

More than ever before, all five boroughs now power the city’s creative economy. From 2005 to 2015, the number of cultural nonprofits in Brooklyn rose by 149 percent (265 to 659), in Staten Island by 133 percent (48 to 112), in Queens by 102 percent (208 to 420), and in the Bronx by 93 percent (72 to 139). And while Manhattan is still the undisputed anchor for creative business employment, with 82 percent of the city’s creative jobs, the other four boroughs have seen enormous growth in small creative businesses and self-employed creative professionals. Between 2003 and 2013, the number of creative businesses in Brooklyn grew 125 percent, in the Bronx 99 percent and in Queens 50 percent. In Manhattan, creative businesses grew just 8 percent over the same period. Amazingly, Brooklyn even beat out Manhattan in the total number of new creative businesses created, with over 1,000 new establishments to Manhattan’s 790.

Creative businesses “have been crucial to the renaissance Brooklyn has experienced over the past decade,” says Carlo Scissura, president and CEO of the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce. “Collectively, they have been the driving force behind our borough’s economic success.”

In some respects, the arts in 21st century Brooklyn, Manhattan and Queens may have become a bit too successful. New galleries and studios have more often than not brought chain stores and luxury condo developments in their wake, in some people’s eyes compromising not just affordability but neighborhood character. At times these newer developments seem to push out the very places that lured the new development to them in the first place. We identified at least 24 music venues (including seven in Williamsburg) and 310 art galleries that have closed their doors since 2011, mainly due to changing neighborhood characteristics and increasing rents. And, since 2005, 22 performing arts theaters have moved or shut down for similar reasons.

Even though chain stores have spread rapidly in all five boroughs and cherished institutions like the Roseland Ballroom and Galapagos Art Space, not to mention Pearl Paint and Penn Books, have been lost, New York has not yet become a monoculture. During the halcyon days of Max’s Kansas City, The Factory and CBGB in the early 1970s, only 18 percent of the city’s population was foreign-born and 36 percent non-white. Today, nearly 40 percent are foreign-born and 67 percent non-white. This diversity has enriched the city’s creative ecosystem.

In this report, we’ve documented the growth of the immigrant arts in New York and found flourishing communities in all five boroughs. They include Ghanaian cultural festivals and Kandyan dance troupes on Staten Island, a Garifuna folkloric and modern dance company in the Bronx, an all-female Chassidic indie rock band in Brooklyn and Terraza 7, a Latin American venue in Queens where jazz musicians jam with traditional artists from Mexico, Colombia and Peru. All of these and many more launched in the last decade.

According to our analysis, the city is home to nearly 200 cultural nonprofits dedicated to different immigrant traditions and ethnicities. Among major American cities, only Los Angeles (with 145) has even half as many. In total, 49,000 immigrants in New York are employed in creative occupations. These New Yorkers account for an astounding 14 percent of all foreign-born creative professionals in the United States.

Still, despite all this economic growth and diversity, and the flourishing of new styles and methods, the future of the arts in this city cannot be taken for granted. Continued growth is not guaranteed, especially now that other cities are investing in their creative sectors, whether in arts districts or fairs like Miami’s Art Basel. Robust communities of artists are flourishing in L.A., Austin, Portland, Nashville and Detroit, not to mention Montreal, London and Berlin.

The appeal of other creative hubs is no mystery. Compared to its peers around the nation, New York City is crushingly expensive. Housing costs in Manhattan exceed those in Nashville by 473 percent, Austin by 401 percent, Philadelphia by 225 percent, Portland by 173 percent and L.A. by 114 percent. In Brooklyn, once an affordable refuge, real estate costs have now surpassed all locations but San Francisco and Manhattan. “The speed at which rents are rising, there won’t be any artists here in 20 years,” says playwright and puppeteer Robin Frohardt. “People can keep spreading out to Queens or the Bronx, but ultimately they want to live in a hub with a community of artists. If everyone is living on the outskirts it won’t be as intense of a culture.”

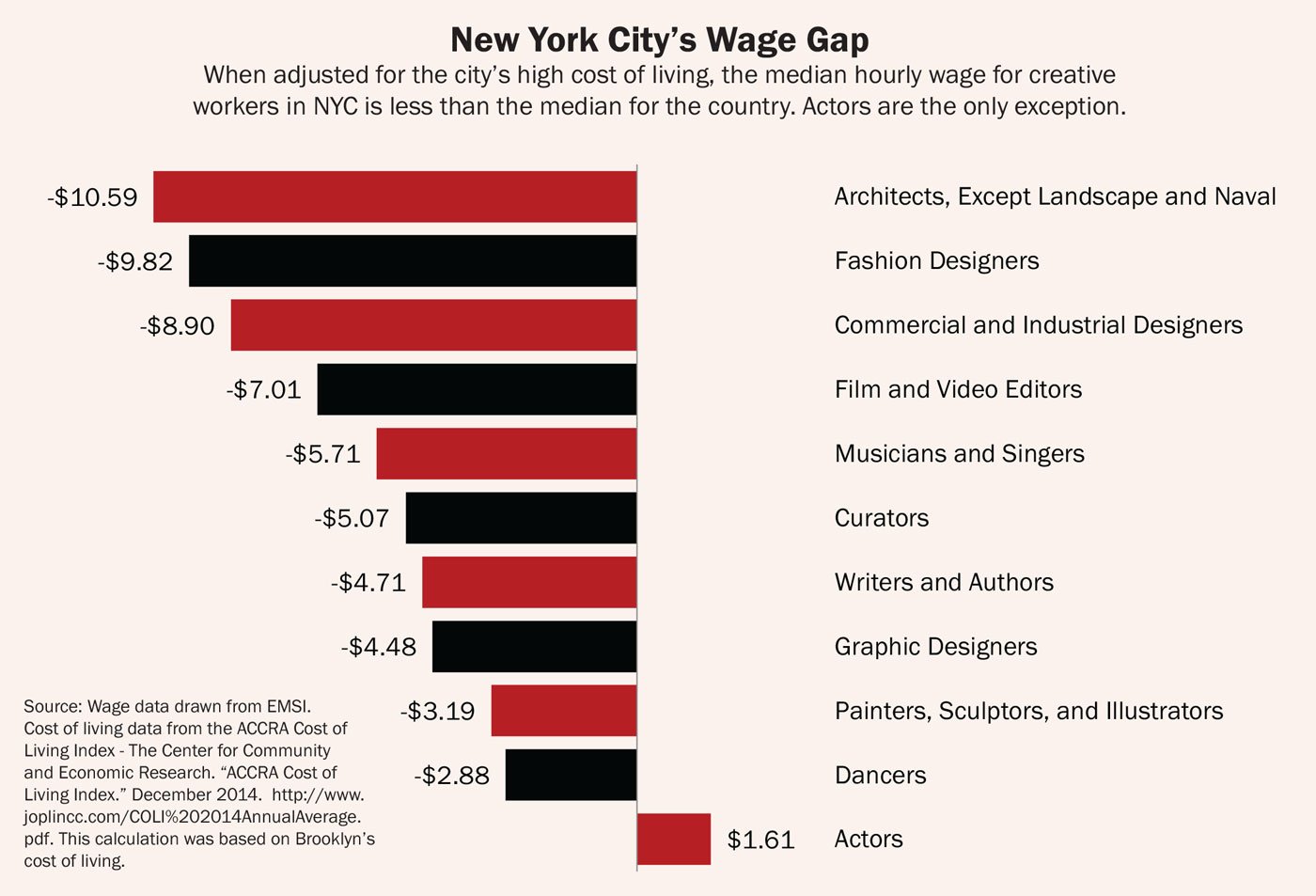

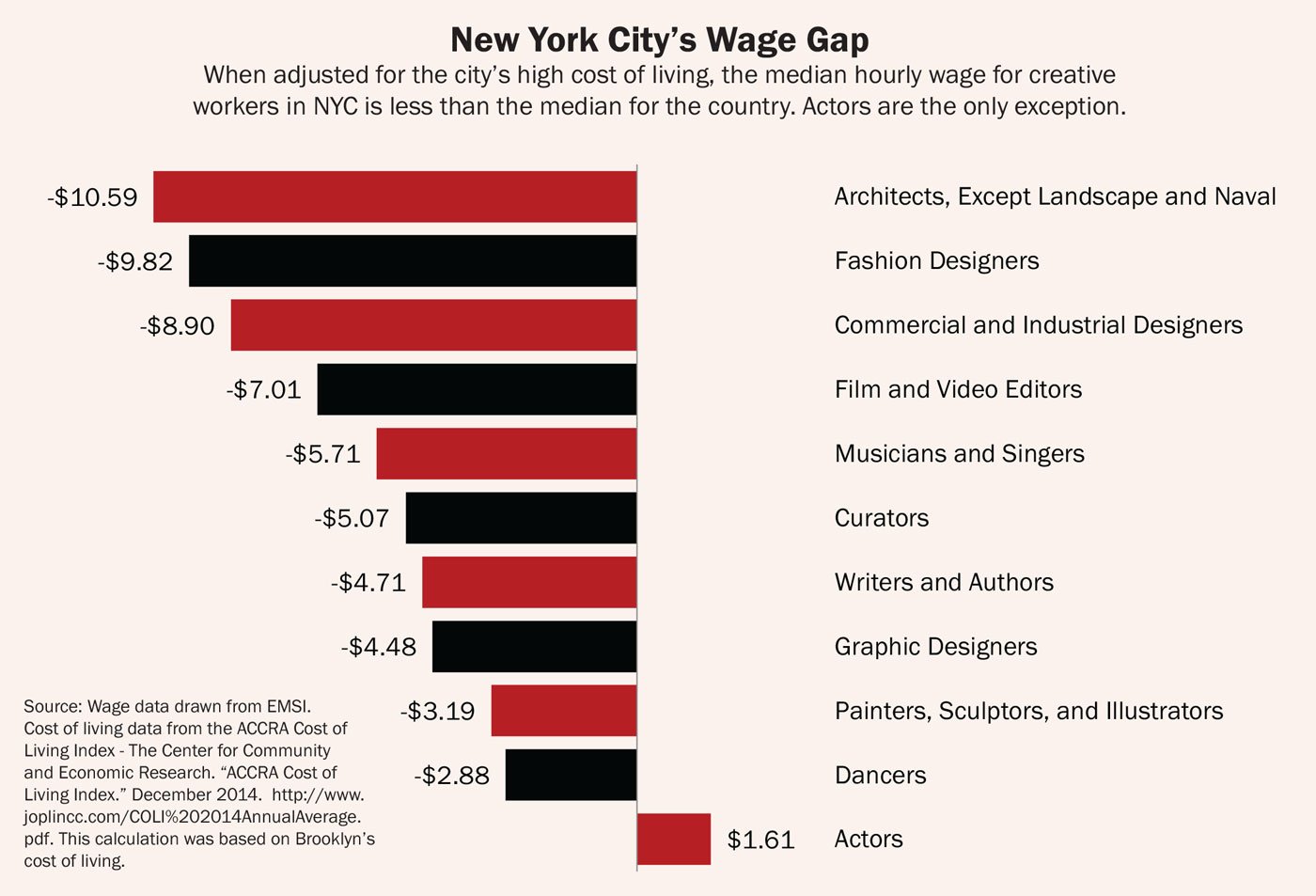

Analyzing median hourly wages for the creative occupations identified in this report, we found that New York’s creative workers earned 44 percent more than the national average. However, when this is adjusted for the city’s high cost of housing, food, transportation and healthcare, the median hourly wage becomes 15 percent less than the national average. And while it is widely believed that for-profit creative workers are thriving in New York as nonprofit artists struggle, the largest wage gaps are actually in the commercial sector. When factoring in a Brooklyn cost of living adjustment, New York architects are paid $10.59 less per hour than the national average for the profession. The gap for fashion designers (-$9.82), industrial designers (-$8.90), multimedia artists and animators (-$7.66) and film editors (-$7.01) is also large.

As we detail in the report, many of the affordability issues are magnified by other obstacles, including mounting student debt among artists and creative workers and the prevalence of unpaid internships in creative fields. In addition, there are a host of other challenges facing the city’s creative sector.

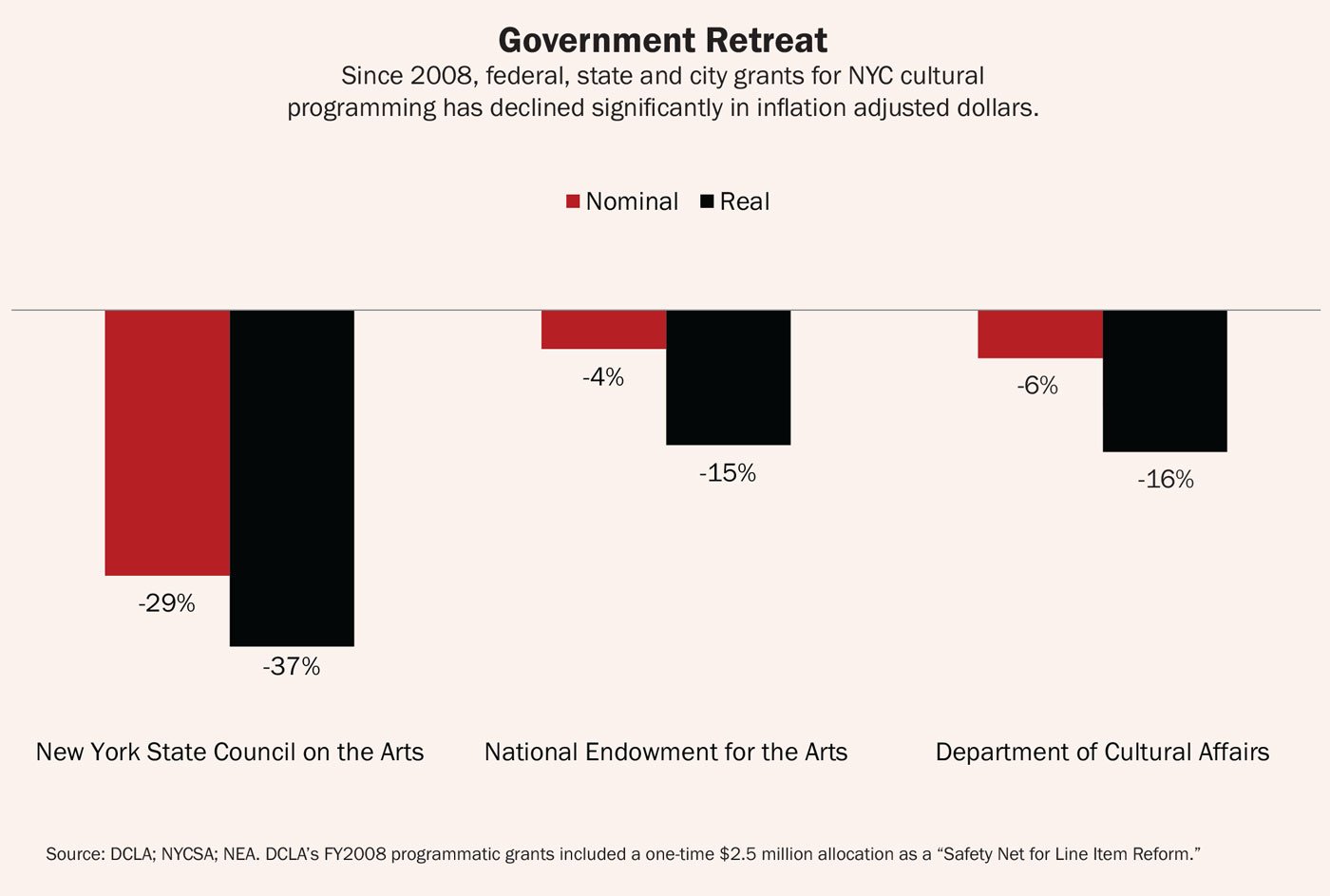

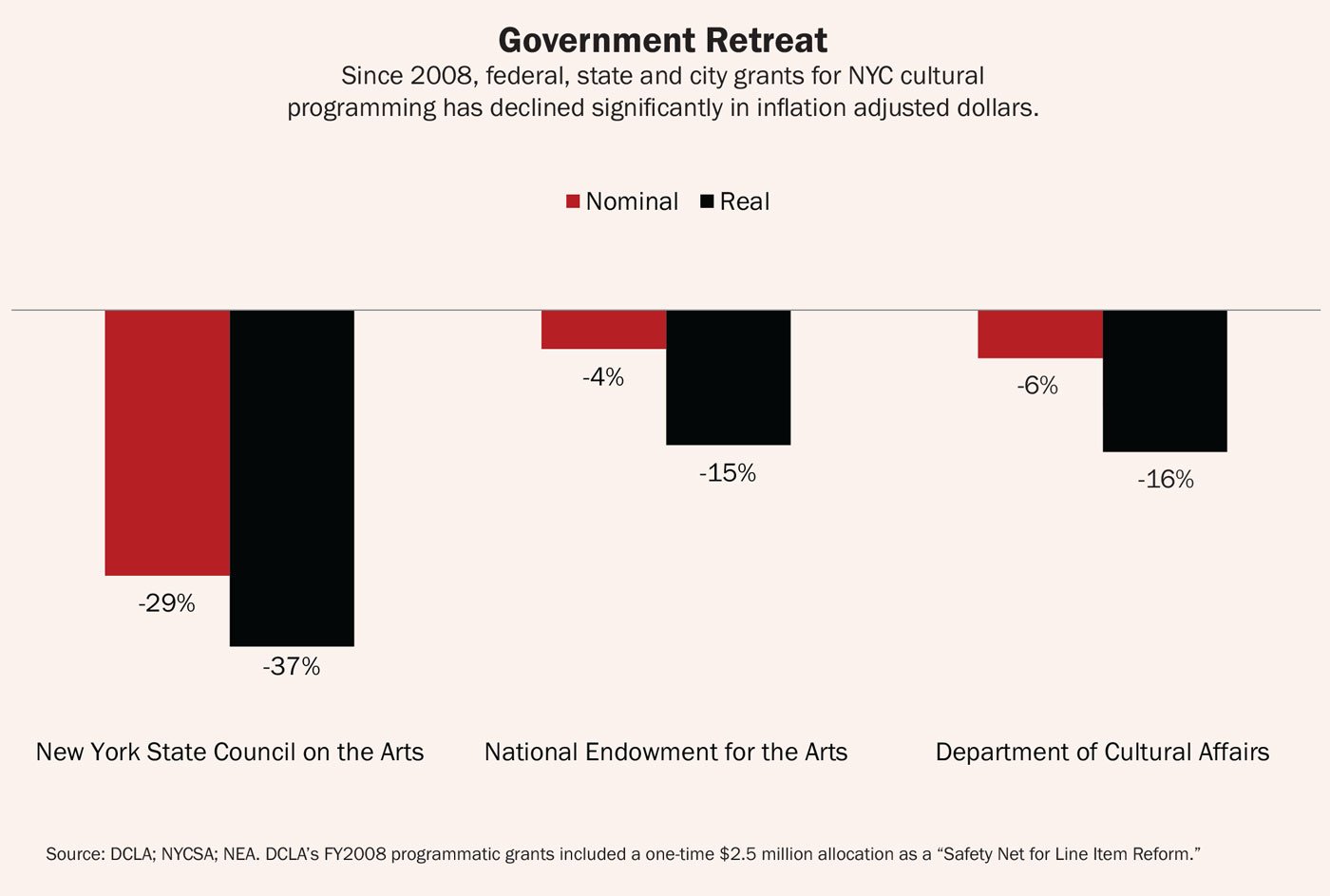

One key challenge has been declining government support for the arts. Though the city government dramatically increased capital spending on cultural groups between 2003 and 2013, programmatic support from the city, state and federal governments has dropped. Since the financial crash in 2008, city support for the 33 members of the Cultural Institutions Group (CIG) fell by 11 percent (21 percent in inflation adjusted dollars). Programmatic grants for city cultural organizations fell by 6 percent during this time, but by 16 percent when adjusted for inflation. Over the same period, federal NEA funding to New York City declined by 4 percent (15 percent, inflation adjusted) and New York State Council on the Arts (NYSCA) funding decreased by 29 percent (37 percent, inflation adjusted).

Declining government support has left cultural organizations in the city more dependent on private philanthropy, a source that some can exploit better than others. Larger cultural institutions with well-staffed development departments, expensive fundraising software and extravagant galas can attract wealthy board members and generous donations. Small and mid-sized institutions, particularly those in immigrant and minority neighborhoods, meanwhile, have had a difficult time filling the gap.

Indeed, this report shows that while New York’s cultural sector is strengthened by the presence of so many small and mid-sized arts organizations, a number of these groups lack the tools to reach new audiences and many are struggling to survive. Many of the city’s smallest cultural nonprofits—including a number of the city’s ethnic arts groups—are run by volunteers and have a difficult time establishing and managing their nonprofit status, challenges that make it difficult to apply for government grants. Our research suggests that the city’s mid-sized cultural organizations face even greater threats. We identified 14 mid-sized performance institutions whose operating revenue in 2012 didn’t cover their expenses.

A lack of diversity in the creative sector is another issue that needs to be addressed. In a majority-minority city, it is problematic that just 29 percent of New Yorkers employed in creative occupations—and only 28 percent of visual artists, 27 percent of performing artists and 19 percent of writers and editors—are non-white.

There are already encouraging signs that Mayor de Blasio and his administration will tackle some of these critical issues. In his first year and a half in City Hall, the mayor has announced new initiatives to create housing units and workspaces for artists, increase diversity in the arts and support the fashion industry. Meanwhile, the City Council recently passed legislation mandating the development of the city’s first comprehensive Cultural Plan.

But given how important the arts and the broader creative sector are to the city’s economic growth and the vitality of its neighborhoods, Mayor de Blasio and other policymakers at the city and state level will need to do even more to address the mounting threats facing New York’s artists, arts organizations and creative industries. To that end, this report concludes with over 20 achievable recommendations for government, cultural and philanthropic leaders to strengthen the creative sector. These include: new revenue sources for artists, arts institutions and arts education, drawn from the hotel tax, the billboard tax and a new creative schools fund; strategies for addressing affordability, such as developing cheap studio and performance spaces in underutilized public buildings, including state-owned psychiatric hospitals, and expanding artist residencies at senior centers, public libraries, churches, and homeless shelters; community development initiatives that make creative use of tax and development incentives to strengthen arts organizations and arts districts, especially in the boroughs outside of Manhattan; a work-study program that provides municipal jobs for arts, film and design students; and dedicated funding pools for mid-sized organizations and artist collectives.