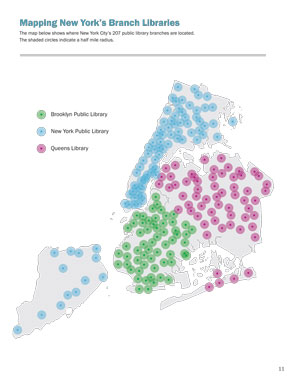

Despite their rising performance indicators, New York City’s libraries are neither in a state of good repair nor keeping up with the needs of 21st-century users. The main driver of this status quo is insufficient funding. Between fiscal years 2004 and 2013, the city spent $503.7 million on capital improvements for the city’s public libraries, a woefully insufficient amount given the overwhelming infrastructure needs, age of the branches and increasing number of New Yorkers using these resources.

Beyond inadequate funding levels, however, the libraries are hamstrung by a broken system that bases funding levels on the decisions of individual elected officials rather than an empirical assessment of building needs. While it grants them some level of independence, the nonprofit status of the three systems (rather than being city agencies) positions them poorly for securing their place among mayoral priorities. Though parks, schools, cultural institutions and other city entities receive significant amounts of their capital funding from the discretionary funds of individual City Council members and borough presidents, the libraries receive a majority of their funding this way. Between fiscal years 2004 and 2013, 59 percent of the libraries’ capital commitments came from City Council and the borough presidents, and only 41 percent came from the administration. Of all city agencies, only the Department for the Aging comes close to this level of dependence on the discretionary funding process, with 53 percent of its capital funds coming from borough presidents and City Council. In the same ten year period, the Department of Parks and Recreation received 21 percent of its capital funding this way, and the Department of Cultural Affairs 41 percent.

What’s more, administration funding is much more likely to be for high-profile projects such as NYPL’s Central Library Plan for the landmark Schwarzman building on 42nd Street. More than half of the administration’s $257 million in appropriations since fiscal year 2010, for example, were directed toward that single project, though NYPL has since decided to change course and use a majority of those funds to renovate the Mid-Manhattan library, which has $100 million in repair needs.

Raising funds through the discretionary process requires the library systems to prioritize projects and shop them around to local elected officials, starting with the local City Council representative and the borough president and ending with the Council speaker and mayor at the very end of the process. Unlike agencies such as the Department of Transportation or the Department of Education, which negotiate funds directly with the administration for systematic improvements (e.g. road resurfacing by lane miles, school expansions by seats), the libraries can’t assume that basic repair and expansion needs will be met. And while some lump-sum appropriations have started to be made, they are not consistent enough for libraries to rely on them for capital planning.

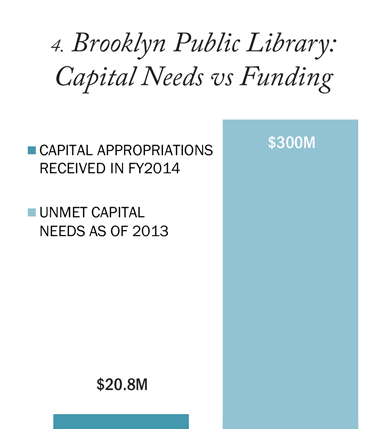

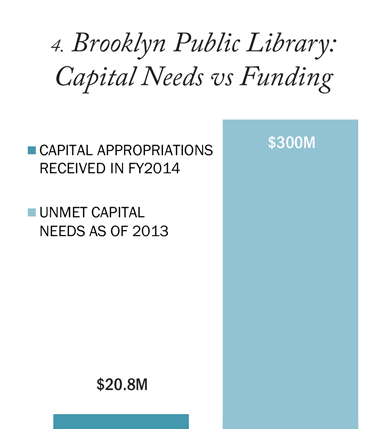

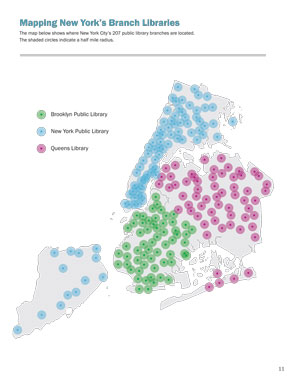

Since a lot can ride on the willingness and interest of local representatives, and since in some districts libraries have to compete with higher-profile projects from cultural groups or parks, funding levels can vary widely from borough to borough and district to district. As our analysis of the last five years of capital appropriations shows, some boroughs have received more support from local representatives than others. Between fiscal years 2010 and 2014, Queens received $50 million from Borough President Helen Marshall and $56.9 million from the City Council. By comparison, Brooklyn received only $4.4 million from Borough President Marty Markowitz and $30.4 million from the City Council during the same period. In fiscal year 2014, despite $300 million in unmet capital needs, Brooklyn received just $7.5 million in capital funds from the City Council and $13.5 million from all other sources.

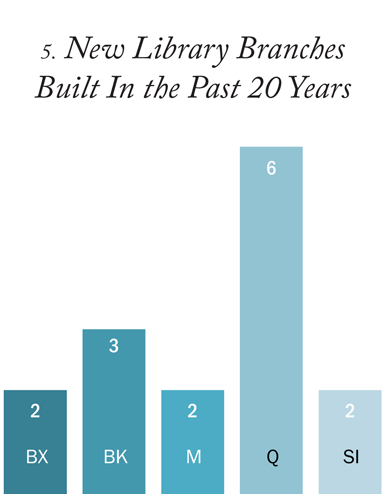

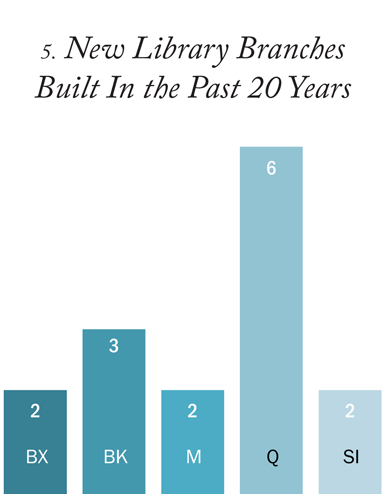

As a result of this broken funding system, New York has only built 15 new or replacement libraries in the past 20 years. Since 1995, when it built two branches, Brooklyn has managed to build just one new library and fully renovate eight others. This is wholly inadequate when the average library in the city is over 61 years old.

Other cities across the country have made their aging libraries a priority and have invested hundreds of millions in rebuilding and replacing them. Over the last 20 years, Chicago, Seattle, Los Angeles and San Francisco have all launched capital improvement campaigns resulting in new or fully renovated libraries for over half of their physical plant. In Seattle, the library passed an ambitious ballot initiative with more than 70 percent approval so that it could build a new 340,000 square-foot central library and renovate or rebuild every branch in its system. Ninety percent of the branch libraries in LA, 88 percent in San Francisco and 75 percent in Chicago were either renovated or rebuilt as part of those cities sustained capital campaigns. Though construction on new branches has just begun, the Columbus Metropolitan Library launched a campaign in 2010 to more than double its overall footprint by the year 2030. As in Seattle, the library’s proposed ballot initiative won the support of more than 65 percent of voters, despite the sour economy. In Chicago, former Mayor Richard M. Daley tied library investments to broader community development goals, replacing vacant lots and liquor stores with new library buildings.

New York City’s charter doesn’t allow the libraries to take a capital improvement plan directly to voters, though given the results from other cities one suspects it would have an excellent chance of passing if it did. But the Bloomberg administration’s approach to cultural groups could serve as a model for what might be done if the de Blasio administration were to make libraries a priority. Between 2004 and 2013, the Bloomberg administration spent $2.1 billion on cultural facilities, or roughly double what his predecessor spent over the ten years prior to that. Increased capital spending on cultural groups made sense for an administration that was trying to position New York as a prominent tourism destination as well as a global capital for finance, law, advertising, media and technology, since world-class art museums and theaters are an enormous draw for both high-end talent and tourists. But as a new administration turns its attention to quality neighborhoods, affordability and skills development for those New Yorkers who have fallen behind in today’s knowledge economy, there is a strong rationale for making a similarly large capital investment in the city’s libraries. Embedded in communities, these comparatively small buildings may keep a modest profile, but they are enormously important to neighborhoods in need of strong civic spaces, students in need of after-school enrichment, and adult learners in need of literacy training.

Doubling capital spending on libraries over the next ten years would add up to approximately $1.1 billion, or enough to significantly rebuild over 100 libraries across the city, including all the libraries most in need. But the de Blasio administration and City Council shouldn’t stop there. They should do what cities from Chicago to Seattle have done and undertake a comprehensive campaign to modernize services and put the libraries on a more sustainable path for the millions of patrons who depend on them. This would not only bring more of the branches into a state of good repair, it would unleash their potential for community development and individual economic empowerment.

As we detail in the blueprint at the end of this report, a comprehensive ten-year capital plan and vision for the libraries would reform and clarify the capital funding process, strengthen the management of capital projects, and create operating efficiencies by further consolidating the libraries’ book processing and delivery activities. Rather than continuing the time-consuming and piecemeal approach to renovations that has led to such disappointing results over the last ten years, this new approach would allow the libraries to create a more predictable pipeline of major projects and serve as a catalyst for commonsense reforms in the approvals and contracting process. A comprehensive and well-funded capital plan would give the city an opportunity to better leverage libraries for the administration’s affordable housing, resiliency and community development agendas: In the blueprint, for example, we identify ten library properties that could support significant new affordable housing developments and provide several examples of how library investments could be tied to nearby developments in order to support a stronger, more inclusive community.

Moreover, a capital plan that came with guaranteed funds would finally allow the libraries to do more long-term planning of their own. Not only would the libraries be able to open up hundreds of thousands of square feet of underutilized space, they would be given a chance to more clearly articulate the network of services they offer and how they are distributed between the branches. Larger hubs could support smaller neighborhood branches with a more comprehensive set of services and longer hours, and small retail branches could help them affordably expand their footprint in underserved neighborhoods. These outposts could serve as pick-up locations for online book orders while using the vast majority of their space for onsite services targeted at specific community needs. Just as important, the libraries would be able to clarify their role vis-à-vis other city agencies, particularly the Department of Education but also the Department of Consumer Affairs, the Department of Youth and Community Development, the Department for the Aging and the Department of Small Business Services. They also would be able to build relationships with community partners through a more deliberate and strategic community engagement process.

Unlike other cities across the country, New York has not thought strategically about these critical community assets—much less developed a comprehensive plan that could address their many inefficiencies—since Andrew Carnegie’s initial donation at the beginning of the last century. With this blueprint, we hope to start a conversation that will change that.

This was the introduction to Re-Envisioning New York's Branch Libraries.

Read the full report (PDF).

View the Key Findings from the report.

View the charts and tables from the report.